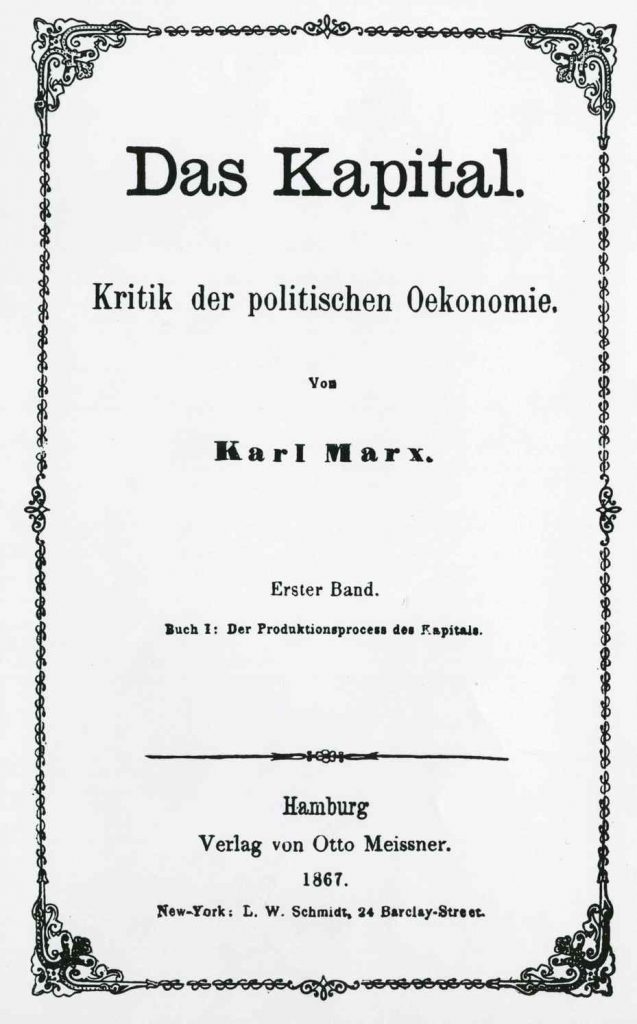

On September 14, it will be exactly 150 years since the publication of Capital: Critique of Political Economy, the first volume of Karl Marx’s epochal Das Kapital. The historicity of the book can be gauged by the fact that this first of three bulky tomes was published by a Hamburg publisher two years after the American Civil War but well above a decade before the incandescent bulb was invented. Capital however, literally acted as the bulb that shone a light on many a way.

Considered as the second most influential book after the Holy Bible, Capital acted as the veritable bible for the working class for well over a century. For several generations of people, Marx was the guru and Capital the holy book. The first volume was the only one published during the lifetime of Marx who died in 1883. The other two parts were published by Frederick Engels based on notes and drafts he found in Marx’s study.

Having lost the position of éminence grise among top titles of the publishing industry in the early 1990s, the labored work of Marx staged a comeback in public imagination in the wake of the global financial crash. The uncertainties triggered by the crisis amplified the viewpoint that capitalism, despite the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, remained inherently crisis-ridden and fallible. People turned to Das Kapital once again in attempts to search for explanations.

The renewed interest in the three-part 2,000 pages packed with printed words in smaller than average font size, confounded most people especially given the ease with which the book was pronounced irrelevant and outdated in the contemporary world. Obviously, the book holds something besides being the status symbol that it once was among the majority of its collectors.

For a book that is recognized for its literal density and polemical tangents that Marx indulged in with writers and commentators who do not resonate with contemporary readers, Capital‘s survival is demonstrative of it holding a key to unraveling many a perplexities of modern-day capitalism. Indeed, the Capital‘s astonishing rebirth in the past decade provides evidence that it is still looked as a tool capable of providing wonderful foresight and for its role in setting in motion several scenario-altering developments in the 20th century.

In the 21st century, Capital may fall a shade short of providing a template for the future, but it has proved that it is not yet a relic of the past. Discussing various facets of the Capital in a way will also set up the impending bicentenary of Marx’s birth that must be celebrated with gusto next year in May.

Capital was undoubtedly Marx’s magnum opus published almost two decades after the much popular and stirring Communist Manifesto of 1848. It would be a mistake to look at Capital as a dry economic, or socio-economic treatise. The book is what British journalist and writer, Francis Wheen, wrote in his biography of Das Kapital, a “radical literary collage–juxtaposing voices and quotations from mythology and literature, from factory inspectors’ reports and fairy tales, in the manner of Ezra Pound’s ‘The Cantos’ or Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’. Das Kapital is as discordant as Schoenberg, as nightmarish as Kafka.”

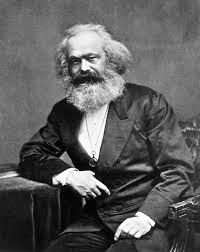

In a letter to Engels, Marx penned his self-description: a creative artist or a “poet of dialectic”, never once an economist. For him, his creation, which kept missing publishing deadlines with impunity, was an “artistic whole.” American writer Marshall Berman wrote that the bearded, saint-like figure was “one of the great tormented giants of the 19th century – alongside Beethoven, Goya, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, Nietzsche, Van Gogh – who drive us crazy, as they drove themselves, but whose agony generated so much of the spiritual capital on which we still live.”

Much of Marx’s literary agony stemmed from ceaseless revisiting what he had already accomplished. He would invariably begin each day, week, month and year by assessing if previous postulations required revision. As a writer and thinker, Marx maintained perfect balance between the intensely self-confident and a writer continuously burdened with self doubt. In a line in the Preface to Capital, Marx provided indication of who he assumed was his archetypal reader: someone “willing to learn something new and therefore to think for himself”. Undoubtedly, his reader in Marx’s mind was little but his own alter ego.

For Marx, there was to be no finality in public debates and he would have been flummoxed when surveying many contemporary societies, including today’s India. He would have surely concluded that any creative thinking was not possible with such a closed mindset. In contrast to today’s growing arrogance about one’s formulations, Marx made no such closure for he left his masterpiece incomplete.

Indicative of his state of mind and shortly before he handed over Capital: Critique of Political Economy to the publisher, Marx asked Engels to read Honoré de Balzac’s ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ which he termed as being “full of the most delightful irony.” Wheen wrote that there is no evidence if Engels heeded his friend’s prompt or not. But the tale mirrored what was in Marx’s mind: creative artists cannot escape intense torture if they wish to remain true to the spirit of inquiry and revision.

‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ was the story of the legendary artist, Frenhofer, and Marx found strength in this 1831 publication probably because it was Balzac’s most passionate shot at dissecting the travails of being an artist. The legendary artist in the tale labored for a decade over a painting which he hoped would depict reality in totality and in an unprecedented style. But when the final canvas is unveiled, his fellow artists see nothing but haphazard strokes collectively representing little but chaos. The painting is damned and Frenhofer burns all his paintings and commits suicide.

Marx, thankfully, committed no such act of folly but the state of his mind was mildly similar if not a replica. Throughout the writing of Capital, he repeated what Balzac made Frenhofer articulate: “Alas! I thought for a moment that my work was finished; but I have certainly gone wrong in some details, and my mind will not be at rest until I have cleared away my doubts.”

According to Berman, Balzac’s description of Frenhofer’s canvas matches depictions of 20th century abstract paintings. He argued that chaos and incoherence for one age has potential to transform into tremendous meaning and beauty in another age. This possibly explains why after being termed to have been “settled”, not just Capital but Marx too appears to have been picked up, this time less a gospel or guru but more as a suitable tool to assist in interpreting contemporary crises in capitalism.

Capital mustn’t be seen as a divine text that it was once considered by communists. There were aspects in which Marx was unparalleled with his insight and there were areas where he would have served his cause by not venturing into. Making grand predictions was something that would have been best avoided. He was certain of imminent mortality of capitalism and that the first proletarian revolution would occur in industrialized London and not in agrarian Russia. Workers were to be the vanguards of the revolution, according to him. Yet, the peasantry led the way in Russia.

Several of Marx’s theories on social behavior too went awry: he postulated that the working class would do nothing but rise in protest against the ruling classes. Yet, large sections of today’s workers desire no such turnaround but aim to merely ape and follow the path of exploiters. The worker in office or factory aspires to be the boss; stop being the oppressed and join the oppressors.

Where Capital has potential to act as a great analytical enabler, is the strength of its socio-economic analysis that is simultaneously lyrical and dispassionate. As economic reforms result in greater concentration of ownership of means of production and as economy evolves into new forms of ‘production’, characterized as ‘services’, for practitioners of either proletarian or egalitarian politics, Capital has potential to serve as a handy investigative device.

Capital‘s relevance becomes sharper for little has changed from what Marx theorized as three fundamental traits of capitalist production: concentration of means of production; organization of labor and emergence of a global market. Followers of Marx and admirers of Capital erred by viewing it as panacea for all ills. For Capital to live beyond the century and a half that it has done so far, it is necessary to discard it as a totalitarian byword and view it as a referral text.

Over and above, Das Kapital‘s significance lies in its ability to provide unambiguous insight into the human trait that enables us to justify exploiting others. For Marx, capitalism was a metaphor that enabled people to evolve without qualms from the human to the monstrous. Wheen is correct in assessing that “Das Kapital is entirely sui generis” and that there has been “nothing remotely like it before or since.”