On October 9, 1967, in southern Bolivia, near the barren and desolate village of La Higuera, the Bolivian Army, under instructions from the government of the U.S., trapped the isolated guerrilla column led by Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara. Che, a hero of the Cuban Revolution of 1959, believed that Cuba, only 90 miles away from the mainland of the U.S., would remain vulnerable unless other revolutions succeeded in the world. His reaction to the violent U.S. bombardment of Vietnam had been similar, not enough to defend Vietnam, he had said, but it was necessary ‘to create two, three, many Vietnams’. Failure to spark revolution in Congo led Che to Bolivia, where its army trapped him. He was eventually captured and brought to a schoolhouse. Mario Terán Salazar, a soldier, was tasked with the assassination. Che looked at this quivering man. “Calm down and take good aim,” he told him. “You’re going to kill a man.” Che died on his feet.

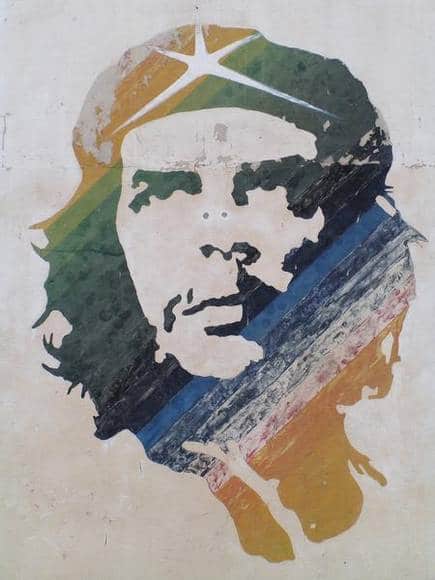

From man, Ernesto Guevara (b.1928) became a myth. It is difficult not to be moved by the life of this Argentinian doctor who became a revolutionary.

Radicalised by reality

His tutelage in revolutionary thought came from his experiences among the leprosy patients of Venezuela and the tin miners of Bolivia, among the revolutionaries of Argentina and the 1954 coup in Guatemala. Reality radicalised him. Only later would he recount that he had been influenced by, as he put it, ‘the doctrine of San Carlos’, his sly reference to Karl Marx.

In 1953, in Mexico, Guevara met Hilda Gadea, a revolutionary from the Peruvian APRA (American Popular Revolutionary Alliance). Gadea schooled Guevara in Marxist theory and in the radical currents then inflaming the region. They moved to Guatemala in September 1954, which was then in the midst of a major struggle against the U.S. government and U.S.-based corporations. A democratically elected government led by Jacobo Árbenz attempted to conduct basic land reforms, which ran afoul of the United Fruit Company. Guevara was marked by the role of this corporation in governing Guatemala.

To his aunt Beatriz, he wrote, “I have had an opportunity to go through the land owned by United Fruit, and this has once again convinced me of the vileness of these capitalist octopuses. I have sworn before a portrait of old, tearful Comrade Stalin not to rest until these capitalist octopuses have become annihilated. I will better myself in Guatemala and become a true revolutionary.”

When the U.S. initiated the coup against Arbenz’s government, Guevara took to the streets. No good came of it. Guevara and Gadea fled to Mexico. It was there that they, thanks to Gadea, met Raul Castro and eventually his brother Fidel. Not long after, Guevara would board a rickety boat, the Granma, with the Castros and 79 others to launch the Cuban Revolution. When their boat arrived in Cuba, the military killed 70 of the revolutionaries. The survivors rushed inland, and with sheer grit proceeded to build the peasant army that eventually overcame the U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista at the close of 1959.

The young revolutionaries inherited a bankrupt country. Batista had shifted $424 million of Cuban reserves to U.S. banks. Loans were not forthcoming. In a late night meeting, Castro asked if there were an economist among them. Che raised his hand. He became the head of the economy. Later when Castro asked him about these credentials, Che answered that he thought Castro had asked, “Who is a communist?” Che took to his task with energy and determination. The U.S. had set an embargo against the island in 1962. It suffocated Cuba. The Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano went to interview Che in 1964. “I don’t want every Cuban to wish he were a Rockefeller,” Guevara said. He wanted to build socialism, a system that “purified people, moved them beyond egoism, saved them from competition and greed”. It was a daunting task, made difficult by the poverty of the treasury and of the population; although the Cuban people’s spirit drove them to volunteer their labour to build their resources.

The Cuba years

“Cuba will never be a showcase of socialism,” Guevara told Galeano, “but rather a living example.” It was too poor to become paradise. It could however exude love for its own people and for the world. For Guevara, love was everything, key to his idea of socialism. In a letter to his five children written en route to Bolivia, Guevara said, “Always be able to feel deep within your being all the injustices committed against anyone, anywhere in the world. This is the most beautiful quality a revolutionary can have.”

The afterword

As for the fate of those who killed Guevara 50 years ago, Bolivian dictator René Barrientos died a year later when his helicopter burst into flames. General Joaquín Zenteno Anaya, who led the operation against Che, was shot to death in the streets of Paris. Major Andrés Selich Chop, who led the Rangers to capture Che, was killed by the dictatorship of Hugo Banzer. Monika Ertl, a member of the National Liberation Army of Bolivia, killed Colonel Roberto Quintanilla Perez, who had announced Che’s death to the world, in Hamburg.

Mario Terán Salazar, the soldier who shot Che, went into hiding. Many years later, in 2006, the Cuban government operated on Che’s killer to remove a cataract from his eye without charge. Che’s legacy was not revenge. It remains a doctor’s love for humanity.