Last week, CNN’s Jake Tapper interviewed Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and asked if he thought President Donald Trump’s punishing response to hurricane-ravaged Puerto Rico had something to do with “race or ethnicity.” Sanders hesitated a bit but ultimately said, “We have a right to be suspect.”

The relative surge in coverage about Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria has floated previously avoided terms like “colony” to describe the island’s troubled relationship with the U.S. rather than the misleading “commonwealth,” part of the official names of states like Massachusetts and Pennsylvania.

Yet, as Sanders’ hesitation suggests, the racial frame is still largely missing.

Top journalists and government figures rarely mention race as a factor in understanding Trump’s negligent response to the hurricane or the U.S. presence in Puerto Rico more generally. And if race is alluded to, it tends to appear in op-eds and not in regular reporting, unless voiced by a celebrity like the British comedian John Oliver, who called out the president’s behavior as “horribly racist.”

Equally significant is that though an increasing number of prominent African Americans, including comedians Wanda Sykes and Michael Che and Flint, Mich., Mayor Karen Weaver, have expressed support or pointed to the racial politics of Hurricane Maria, its deadly impact has to date not been cast as politically urgent. The lack of a massive outcry led the black news site Hudson County Chronicles to declare, “Puerto Rico Disaster Exposes Black and Brown Divide.”

In other words: Puerto Rico’s crisis is not generally seen as a racial matter. But it should be.

To start, the rationale to acquire colonies in the Pacific and Atlantic on the heels of the Spanish-American War of 1898 rested on the notion of white racial superiority. The entire legal edifice that defines Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory that “belongs to but is not part of the U.S.” is unapologetically racist.

Through a series of decisions known as the Insular Cases (1901-1922), the Supreme Court opted to create a new body of law to distinguish incorporated territories on the path to statehood from the newly gained possessions (Guam, Philippines, Puerto Rico), and justify that the U.S. Constitution would not entirely apply.

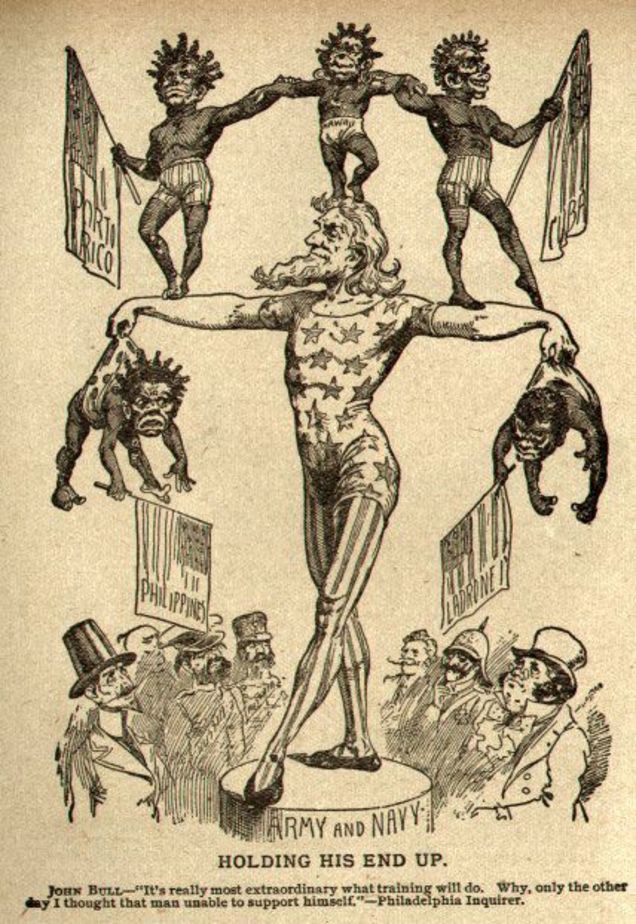

The main reason given was that territorial inhabitants were unfit and not mature enough to self-govern or be part of the union because of their condition as “uncivilized” and “alien races.” This view was etched in the cartoons of the early colonial period, in which Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Filipinos and Chamorros were often drawn as black “pickaninnies” in need of Uncle Sam’s paternal direction.

Not surprisingly, the court that ruled on these cases was nearly made up of the same justices who reached the 1896 “separate but equal” decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, upholding state racial-segregation laws. As current U.S. District Judge Juan R. Torruella summed up, the Insular Cases were “a more stringent version of the Plessy doctrine: the conquered lands were to be treated not only separately, but also unequally.” Even further, while Plessywas eventually overturned, the Insular Cases have not been. The Supreme Court still routinely relies on them to decide cases before it.

In addition to a new type of law, the U.S. created a new type of citizenship. Through the little-known Jones-Shafroth Act of 1917, Congress extended U.S. citizenship to the people of Puerto Rico. But unlike American citizens living in the States, Puerto Ricans were not entitled to fundamental rights such as voting for president or electing a proportional, voting delegation to Congress.

The reasons against full citizenship are also entangled in racist logic. For some policymakers, the risk was that given their makeup as “lesser races,” the people of Puerto Rico simply could not understand “Anglo-Saxon principles.” For others, the fear was that political incorporation would enable nonwhites to make laws for or govern not only themselves but also the “whole American people,” and even “[give] the republic its presidents.”

Ultimately, to the extent that Puerto Rico was considered too densely populated to make large-scale white settlement viable (as would happen in once-Mexican-majority territories like Arizona and New Mexico), unincorporation and colonial citizenship became the legal wall keeping Puerto Rico out of national governance.

As such, the granting of U.S. citizenship 100 years ago had little to do with citizenship rights. Instead, in response to the growing opposition to American colonial rule, its primary aim was to promote loyalty to the U.S., criminalize pro-independence action, and underscore that the island was not a polity but American property. As colonial Gov. Arthur D. Yager put it, the U.S. citizenship of Puerto Ricans simply indicated that “we have determined … the American flag will never be lowered in Puerto Rico.”

Certainly, Congress eventually “allowed” Puerto Ricans to elect their own governor in 1948 and draft a constitution in 1952. But Congress reserved the right to approve the constitution, and the unincorporated territory doctrine remained intact. Sovereignty over the territory still legally resided not in the people of Puerto Rico but in a group of mostly white men sitting 1,500 miles away in Washington, D.C.

Often overlooked by legal scholars, the “low” racial status of Puerto Ricans followed them into the Diaspora. As part of Operation Bootstrap, Puerto Rico’s economic modernization policy of the 1940s, hundreds of thousands were encouraged to migrate to the U.S. through propaganda and measures such as lowering airfare prices so the poor could afford one-way tickets to cities like New York, Chicago and Philadelphia.

Yet if settling in any of the 50 states theoretically made Puerto Ricans “first class” citizens who could now vote for president and enjoy full constitutional rights, they continued to be treated as nonwhite. Accordingly, Puerto Ricans experienced many of the same denigrating conditions familiar to African Americans: housing segregation, inferior schools, job discrimination, media vituperation and everyday violence. Importantly, this entry-level experience proved to be enduring for many: In affluent New York City, where close to a million Puerto Ricans reside, they remain among the poorest residents, with a third living in poverty.

So although it has become liberal sport to insist on how different Trump is from everything and everyone else that preceded him, the president’s response to the hurricane is consistent with American colonial history. This is manifested in both the slowness and limited scale of assistance during Hurricane Maria, and by the fact that when local leaders criticized him for it, Trump defended himself by invoking century-old racial stereotypes of Puerto Ricans as lazy and ingrates who “wanted everything to be done for them.”

Trump’s brief visit to Puerto Rico’s “best” neighborhoods also exposes another racial layer. Whereas elsewhere in the U.S., Puerto Ricans are collectively considered nonwhite, on the island, additional racialized power dynamics apply. Some of the poorest and hardest-hit areas like the municipality of Loiza are predominantly black. Assistance, however, has tended to come faster to less affected but more affluent and whiter cities like Guaynabo. Equally revealing, island politicians and government spokespeople are largely light-skinned Puerto Ricans.

All of which is why the crisis in Puerto Rico needs to be part of the national and global anti-racist dialogue. As evidenced by the hurricane’s rising death toll, which will at least reach the hundreds, failure to do so will likely continue to cost lives. It will also make the task of expanding coalitions more difficult and limit the potential to address both old and new challenges like climate change.

To prevail against the present and coming storms, people may require not only better building materials but also a greater understanding of how racism takes many shapes and is constantly reassembling.