Frantz Fanon attended the All-Africa Conference convened by Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah in 1958. He met with anticolonial leaders, including Congolese Patrice Lumumba and Cameroonian Felix Moumié. During the Second Congress of Black Writers (Rome 1959), he expanded his network with activists from the Portuguese colonies, including Amical Cabral. In November 1960, agents of the French secret service fatally poisoned Moumié in Geneva. Lumumba was murdered and disappeared in 1961, while Cabral was assassinated in 1973. Fanon, Moumié, Lumumba, and Cabral shared the dangers associated with anticolonial resistance. Fanon, the “hardest realist as well as a passionate revolutionary” was impatient to get involved in the battlefield. The closest he came was during the Mission to open the Southern front to bring arms across the Sahara into Algeria: “These trans-Saharan paths the militants were tracing were, for Fanon, the living veins of African unity.” The mission exhausted Fanon. But the fatigue turned out to be the early symptom of leukemia. November 11, 1961, Fanon mustered his last energies to write what will become his farewell letter to his brother. Black British filmmaker Isaac Julien tells this story in Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask (1996):

My Dear Joby, now things are a bit better. The illness that affected me while I was in Tunis was a chronic leukemia which has now turned into an acute leukemia. Around September 20, my situation became very serious. I decided to go to the United States to an institute specializing in leukemia. Just as well, eight days after I arrived, I had a series of cataclysmic hemorrhages. I was between death and life.

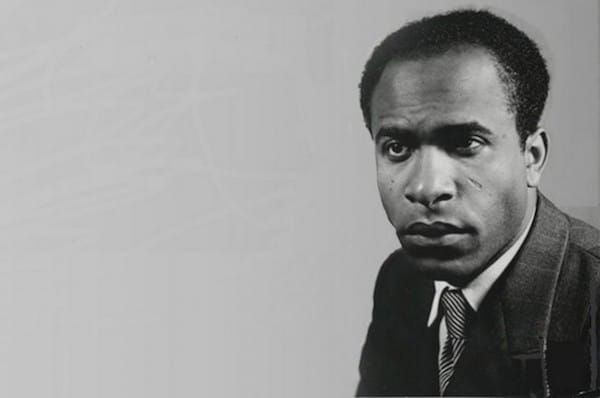

Racing against death, he started writing, or rather dictating The Wretched of the Earth. The book represents the ultimate act of resisting “the reality of the sickness that was coursing through his body, destroying his life-force”. In the totemic work, Fanon “reaches his full height as analyst of decolonization and brilliant critic of its tragic limitations.” Written with the acute and tragic consciousness of the utmost urgency, Fanon mobilized his last energies to defeat the slow death that is the lot of the colonized. Born in Martinique on July 20, 1925, he died in Washington, D.C. on December 6, 1961, and is buried in the Algiers martyrs’ cemetery, a tribute to his contribution to the Revolution.

Leo Zeilig defines himself an as internationalist with the conviction that “for a truly human society to rise, national consciousness must be transcended, dissolved and broken down on the global terrain of global society (and struggle).” In his recent book, Frantz Fanon. The Militant Philosopher of Third World Revolution, Zeilig takes the reader on an analytical discovery of the revolutionary of the Algerian Revolution, the uncompromising critic and prophetic voice of the misadventures of post-independence, the psychiatrist who sought to revolutionize the practice of psychiatric. Zeilig, however, impeaches Fanon for having deviated from Marxist orthodoxy, activating old battle lines between postcolonial theory and Eurocentric paradigms. A less Euro-centric understanding, however, delegitimizes such an impeachment, as I demonstrate below.

Fanon’s road to becoming an ardent defender of revolutionary struggle started with his voluntary enrolment in the French forces against Nazism. He was then convinced of the need for participating in struggles for justice and freedom. Martinique was under the pro-Nazi Vichy government. On 25 November 1944, Fanon, injured in combat against German forces, would be awarded the Croix de Guerre for his bravery. After completing his medical studies in psychiatry, he was sent to Pontorson in the Brittany region of France. Believing that his expertise was needed in the colonies, he requested a transfer. Fanon argues that in underdeveloped countries, life is perceived as a struggle against an omnipresent death that may comes in the form of famine, disease or high infant mortality. Life is an exception, a suspended state of the omnipresent death. He discovered that the European medical profession, instead of being the welfare department in the colonial regime, was an integral part of colonial domination. He subsequently resigned from his position at the Blida-Jointville hospital in Algeria, a repudiation of colonialism as well as a stinging rebuke of the unethical practices of the medical profession.

He traveled to France where members of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) hosted him. He met with French intellectuals sympathizers or supporters of Algerian independence before moving to Tunis, headquarters of the exiled leadership of the FLN. The Algerian struggle inspired and influenced Fanon’s political thinking. However, the disciplined militant responded with a creative theoretical framework that has come to be one of the most influential references in the understanding of anticolonial movements. Fanon, had he had a chance to live long enough, would have been thoroughly disenchanted with the failures of governments emerging from anticolonial struggles. He was, during his times, disillusioned by the ambivalence of the Internationalist Left. The excesses of Stalinism may justify Fanon’s distrust of Marxism. Stalinism also theorized colonies as being backward and in need of capitalist development, further complicating the “global project of emancipation with the left”. In line with this ideological regimentation, the French Communist Party posited that only “the working-class movement achieving socialism in Europe could deliver freedom to Algeria.” The French Communist Party voted for the total war against Algerians fighting for their independence. Fanon indicts the French left’s hesitancy, if not outright opposition, to revolutionary anticolonial armed struggle. Zeilig concedes that the French left was indecisive, but he asserts that the anti-Stalinist left provided “significant and widespread solidarity and political support and active involvement in ideological debates during the Algerian revolution.” His attempts at explaining away the equivocal behavior of the Left then turn to an exposé of Fanon’s perceived ideological illiteracy.

For Zeilig, Fanon disregarded the centrality of the working class as the driving force of the revolutionary process, thereby ignoring the “essence of classical Marxism.” Fanon is therefore guilty of ideological naïveté: “This displays a failure to understand what Marx meant by the pivotal role of the working class and its relationship to the oppressed.” This ignorance made him vulnerable to the seduction of Maoism, whence the romanticization of the peasantry, one of the doctrinaire’s cardinal sins: “Fanon, like many thinkers of his time, was influenced by Maoist interpretations of socialism, which emphasized the central role of the peasantry in revolutionary struggle while holding a deep suspicion towards the proletariat.” The ensuing “ideological confusion” displaces the working class as “Marx’s agent of political change.” Fanon launched “a long and disastrous intellectual and political hostility towards the African working class (not to mention the love affair with a largely mythical peasantry).”

Zeilig’s book is written with passion and is well-researched, successfully providing both an historical and analytical framework that convincingly restates the meaning of Fanon’s oeuvre for the contemporary moment. However, the author’s allergy regarding entering into a meaningful discussion about eurocentrism when it comes to Marxism is troubling. This argumentative stance denotes an unflinching conviction in the redeeming power of Marxism, without taking into account Fanon’s experiences and insights. Two dogmas appear to shape such a belief, namely the revolutionary dimension of the working class and internationalism. The practice of internationalism sometimes took the form of paternalism, understood as “the policy or practice on the part of people in positions of authority of restricting the freedom and responsibilities of those subordinate to them in the subordinates’ supposed best interest.” In 1956, Martinican Aimé Césaire resigned from the French Communist Party, denouncing what he referred to as communist fraternalism. In this fraternalism, anticolonial activists were regarded as junior partners to be schooled by European mentors.

Following the same dogmatic fraternalism, Yuru Smertin, a Soviet ideologue, in Kwame Nkrumah (1987) lectures Nkrumah for failing to “use the term ‘class’ in its Marxist sense.” He praises Nkrumah’s ideological evolution, yet laments the fact that “like any convert, he only took in the external aspects of Marxism, those which best answered his own needs”. By proclaiming the primacy of revolutionary warfare in the African liberation, Nkrumah was following in the footsteps of ideological deviants: “A left radical ideological trend already existed in Africa at this time which absolutized the force of arms and advocated using it to resolve the domestic social problems African problems faced. Its most important representatives were Frantz Fanon and Ben Barka.” Mao Zedong, Fanon, Che Guevara or Nkrumah who sought revolutionary transformation through armed struggle have all been charged with presenting “the anti-Marxist theory of the absolute priority of armed struggle, which Chinese ideologists tried to disseminate in the newly free nations, was presented as the last word in Marxism.” The defenders of the Soviet shrine accuse Beijing of universalizing the Chinese experience, “in part by making pseudo-revolutionary phraseology, and thrust[ing] it upon Africans without taking the concrete conditions of that continent into consideration”. Zeilig points out the promises and contradictions that emerge from Fanon’s oeuvre. But Fanon cannot and should not be confused with the hollow pronouncements of the Soviets. Students of Marxism would be better served by evaluating the doctrinaire phraseology against the concrete reality experienced by living peoples. Fanon placed the urgency of liberation as his ultimate guide. Compromising the Marxist orthodoxy appears as a lesser crime if it sets oppressed peoples on the path of their emancipation.

Works Cited

Leo Zeilig. Frantz Fanon. The Militant Philosopher of Third World Revolution. London & New York: I.B. Tauris, 224 pages.

Aimé Césaire. “Letter to Maurice Thorès.” Paris, October 24, 1956.

Yuri Smertin. Kwame Nkrumah. (Translated from Russian) Moscow: International Publishers, 1987.