In October 1958, over two hundred writers from Asia and the emerging African nations descended onto Tashkent, the capital of the Soviet Republic of Uzbekistan. Among the participants was W. E. B. Du Bois, who at age 90 had just flown in from Moscow (where he persuaded Nikita Khrushchev to found an Institute for the Study of Africa). Alongside leading Soviet writers and cultural bureaucrats, some of the major figures of the 1930s literary left outside of Europe or the Americas were in attendance: the Turkish modernist poet Nazim Hikmet and his Pakistani counterpart Faiz Ahmad Faiz, the Chinese novelist Mao Dun and Mulk Raj Anand. Though poorly known at the time, some of the younger delegates at that meeting would go on to become the leading literary figures of their countries: the Senegalese novelist-cum-filmmaker Sembene Ousmane, the Indonesian writer Pramoedya Toer, the poet and founder of Angola’s Communist Party Mario Pinto de Andrade, and the Mozambican poet and FRELIMO politician Marcelino dos Santos. By all accounts, Tashkent impressed visitors with its mixture of Western modernity and familiar “eastern-ness,”—an effect carefully curated by the Soviet hosts who sought to make it a showcase city for Third-World delegations.

The gathering that brought all these writers together—the inaugural congress of what would later become known as the Afro-Asian Writers Association—represented the literary front of the Soviet Union’s return to the colonial question after a two-decade-long lapse. The Stalinist state’s geopolitical zigzags and the rumors, confirmed in Khrushchev’s 1956 Secret Speech, of oppressive practices at home had considerably dimmed the flame of the Russian Revolution by the mid-1950s. African and Asian intellectuals’ doubts over the Soviet state’s emancipatory promises were now partly made up by the resources of a world super-power, which interwar Soviet anti-imperialism had lacked. These resources exercised a powerful, if ambiguous, effect on black political life worldwide, resulting, on the one hand, in devastating proxy wars in Angola and Mozambique and, on the other, fueling emancipatory struggles against apartheid in South Africa and Jim Crowe in the US.1

This article will be particularly interested in the cultural consequences of the Soviet engagement with the postcolonial world, namely, in its effect on African letters. As a heir to the literature-centrism of the revolutionary Russian intelligentsia of the late nineteenth century, the Soviet state, down to its very bureaucracy, believed in the capacity of literature to transform society and invested heavily in literary engagements even with societies very different from its own. By the reciprocal logic of the Cold War, the U.S. State Department and CIA, institutions not known as patrons of literature before or after the Cold War had to match those investments. The real beneficiaries of this competition were African writers, interest in whose work significantly increased, as well as readers in the first, second, and third worlds, who were given greater access to those writers.

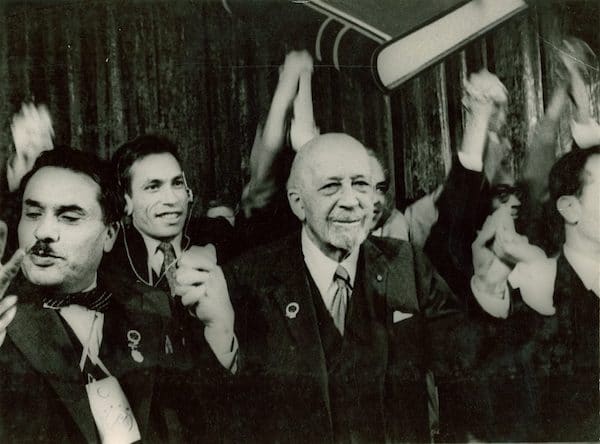

W. E. B. Du Bois speaking with Chinese delegates at Afro-Asian Writers Conference, Tashkent, October 1958. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

The Afro-Asian Writers Association was the main organizational vehicle of the Soviet engagement with postcolonial literatures. Although it fashioned itself as the literary equivalent of the Non-Aligned Movement, the Association was heavily aligned: thanks to Soviet Central Asian writers and readers, the Soviet cultural bureaucracies were able to claim a place on the Afro-Asian table. The Association’s main goal was to forge an international alliance among the literatures of the two continents aimed at consolidating their forces and achieving independence from the publishing centers of Paris, London, and New York. To be sure, there were other, competing literary internationalisms that had set themselves similar goals and sought to command the loyalties of African writers and readers: pan-Africanism, francophonie, literary Maoism, among others. None of them, however, could match the sheer scope of the Association or the symbolic and material resources of the Soviet state. Relying on their experience of literary internationalism in the first two decades after the 1917 Russian Revolution, in their efforts to forge an Afro-Asian literary field, Soviet cultural bureaucracies helped develop four main institutions: international writers congresses, a co-ordinating bureau, a multi-lingual literary quarterly, and an international literary prize.

Ever since the Proletarian Writers’ Conference in Moscow on the Tenth Anniversary of the October Revolution (1927), international writers congresses such as the Popular-Front-era Paris Conference of Writers for the Defense of Culture (1935) or the early Cold-War Wroclaw Congress of Intellectuals for Peace (1948) served as sites for constituting international literary fields and deploying literature as a force for political engagement. Following in that tradition, the 1958 Tashkent Congress of Afro-Asian Writers was only the first of eight Congresses in this history of the Association, the others being hosted by Cairo (1962), Beirut (1967), New Delhi (1970), Alma Ata (1973), Luanda (1979), Tashkent (1983), and Tunis (1988).

As in previous Soviet-aligned international literary organizations, the Afro-Asian Writers Association had a Coordinating Bureau, which was initially located in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Its takeover by Maoists during the Sino-Soviet split of the early 1960s plunged the movement into its first of several crises and resulted for some time in two parallel and competing associations: one dominated by China, which withered during the Cultural Revolution, and another, Soviet-aligned one, headquartered until 1978 in Cairo. The (Soviet-aligned) Bureau’s last head and General Secretary of the whole Association was the South African writer Alex La Guma, who was living for most of that time (1979-1985) in Cuba, doubling as a representative of the ANC. In general, the bureau sought to serve as a depot for literature produced in different parts of the literary Third World and maintain the day-day connections among different national writers’ associations and sometimes government bureaucracies situated at the interface of each particular national culture.

W. E. B. DuBois, Shirley Graham DuBois, Majhemout Diop, Zhou Yang and Mao Dun at the Afro-Asian Writers Conference in Tashkent, October 1958. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Closely related to it was another structure of the Afro-Asian literary field: the Association’s literary magazine, Lotus, which published contemporary prose, poetry, folklore, criticism, and book reviews by African and Asian writers between 1968 and 1991, when the USSR ceased subsidizing it. To try to list the most prominent writers and texts it published would be to list the contemporary postcolonial canon. Initially proposed to Soviet authorities by Faiz Ahmad Faiz and based in Cairo in its first decade, Lotus was forced to relocate to Beirut in the aftermath of the Camp David accords, and eventually to Tunis and Moscow. In its basic idea, the magazine strikingly resembled International Literature, the Moscow-based periodical of interwar leftist literature, and like it, it came out in several languages: French, English, and Arabic. Through translation, it sought to overcome the linguistic, national and regional boundaries dividing their intended audiences and to imagine an Afro-Asian literary community.

The Afro-Asian Writers’ Association also sought to consolidate Third World literature as a coherent field through the Lotus Literary Prize, modeled after the World Peace Council’s Lenin Peace Prize of the early Cold War. Envisaged as the Afro-Asian Nobel for literature, the Lotus Prize helped produce a veritable contemporary Afro-Asian canon: the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish (1969) and the South African prose writer Alex La Guma (1969), the novelists Sembene Ousmane (1971) and Ngugi wa Thiongo (1973), the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe (1975), and his compatriot, the poet, graduate of Moscow’s Literary Institute, and future President of the Union of African Writers Atukwei Okai (1980). Many of the recipients received the award well before they acquired a significant literary reputation among Western publics.

In 1978, as the Afro-Asian Writers’ Association entered its period of decline, mirroring the pitfalls and assassinations of the Third-World project, Edward Said’s Orientalism was first published. Spearheaded by a somewhat different international cultural formation of diasporic scholars, postcolonial studies nevertheless performs some of the same intellectual labor as the Association had done earlier and relies on a literary canon that the Association has helped shape. Thus, even though the Association ceased to exist the same year as its main sponsor, the Soviet state, disappeared from the map, its legacy—a distant echo of the October Revolution—continues to live a spectral, unacknowledged life in the proletarian themes of black diasporic literature, and in the scholarly approaches used to study the literature of the African continent.2

Notes

- For the relationship between the Civil Rights movement and the Soviet state, read Mary Dudziak’s Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). For a study of proxy wars and Soviet support for ANC, see Arne Westad’s Global Cold War: Third-World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007). ↩

- For one of the few studies that delineates the Marxist/Soviet genealogy of postcolonialism, see Robert Young’s Postcolonialism: an Historical Introduction (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2001). For a very plausible explanation how Edward Said could have borrowed his foundational definition of “orientalism” from Soviet sources, see Vera Tolz’s Russia’s Own Orient: The Politics of Identity and Oriental Studies in Late Imperial and Early Soviet Period (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 85-110. ↩