A hundred years later, the question of the historical legacy of the October Revolution is not an easy one for socialists, given that Stalinism took root within less than a decade after that revolution and the restoration of capitalism seventy years later met little popular resistance. One can, of course, point to the central role of the Red Army in the victory over fascism, or to the rivalry between the Soviet Union and the capitalist world that broadened the space for anti-imperialist struggles, or to the moderating effect on capitalist appetites of the existence of a major nationalized, planned economy. Yet, even in these areas, the legacy is far from unambiguous.

But the main legacy of the October Revolution for the left today is, in fact, the least ambiguous. It can be summed up in two words: “They dared.” By that, I mean that the Bolsheviks, in organizing the revolutionary seizure of political and economic power and its defense from the propertied classes, were true to their mission as a workers’ party: they provided the workers—and peasants too—with the leadership that they needed and wanted.

But the main legacy of the October Revolution for the left today is, in fact, the least ambiguous. It can be summed up in two words: “They dared.” By that, I mean that the Bolsheviks, in organizing the revolutionary seizure of political and economic power and its defense from the propertied classes, were true to their mission as a workers’ party: they provided the workers—and peasants too—with the leadership that they needed and wanted.

It is more than ironic, therefore, that many historians, and following them, popular opinion, have viewed October as a terrible crime, motivated by the ideologically-inspired project to build a socialist utopia. According to this view, October was an arbitrary act that diverted Russia from its normal path of development toward a capitalist democracy. October was, moreover, the cause of the civil war that devastated Russia for almost three years.

A modified version of that view is espoused even by some on the left, who reject “Leninism” (or what they believe to have been Lenin’s strategy), because of the authoritarian dynamic that a revolutionary seizure of power and a civil war unleash.

Concrete Solutions

What strikes one most, however, when one studies the revolution “from below,”1 is how little, in fact, the Bolsheviks, and the workers who supported them, were motivated by “ideology,” in the sense of theirs being some sort of chiliastic movement with socialism as its goal. In reality, and above all, October was a practical response to very serious and concrete, social and political problems confronting the popular classes. That, of course, was also Marx and Engels’ approach to socialism—not as a utopia to be constructed according to some preconceived design, but a set of concrete solutions to the real conditions of workers under capitalism. That is why Marx obstinately refused to offer “recipes for the cook-shops of the future.”2

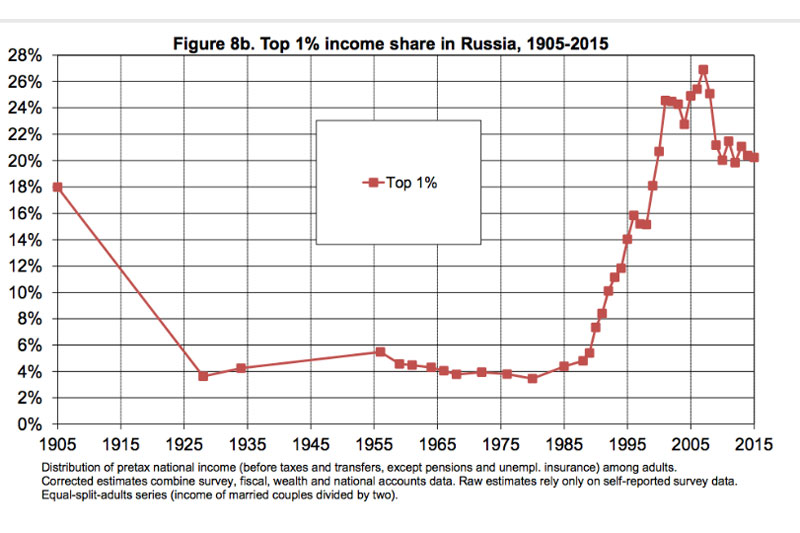

[Chart taken from Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, Gabriel Zucman, “From Soviets to Oligarchs- Inequality and Property in Russia, 1905-2016.” NBER Working Paper No. 23712. —Eds.]

The Bolsheviks, and most urbanized industrial workers in Russia, were, of course, socialists. But all currents of Russian Marxism considered that Russia lacked the political and economic conditions for socialism. There was, to be sure, hope that the revolutionary seizure of power in Russia would encourage workers in more developed countries to the west to rise up too against the war and against capitalism and open broader perspectives for Russia’s revolution. That was indeed a hope, but it was far from a certainty. And October would have happened without it.

Facing the threat of Civil War

In my historical work, I present documented, and to my view, convincing, support for that view of October and I will not attempt to summarize the evidence here. I want rather to explain how painfully aware the Bolsheviks, and the workers that supported them—the party was overwhelmingly working-class in composition—were of the threat of civil war; how much they tried to avoid it, and, failing that, to minimize its severity. In doing so, I want to put into sharper focus the meaning of “they dared,” as October’s legacy.

The desire to avert civil war was why most Bolsheviks, along with most workers, supported “dual power” in the early period of the revolution. Under that arrangement, executive authority was wielded by a provisional government, initially composed exclusively of liberal politicians, representatives of the propertied classes. At the same time the soviets, political organizations elected by the workers and soldiers, were to monitor the government, ensuring its loyalty to the revolution’s programme. That programme consisted of four main elements: a democratic republic, land reform, the eight-hour workday, and an energetic diplomacy aimed at securing a rapid, democratic end to the war. There was nothing of itself that was socialist in that programme.

Support for dual power marked a radical break with the party’s longstanding rejection of the bourgeoisie as a potential ally in the fight against the autocracy. That rejection had been the very foundation of Bolshevism as a workers’ party. It was the reason the party acquired hegemonic status in the workers’ movement during the pre-war years of labour upsurge. That rejection of the bourgeoisie (which was, at the same time, a rejection of Menshevism) had its roots in the workers’ long and painful experience of the bourgeoisie’s intimate collaboration with the autocratic state against their democratic and social aspirations.

The initial support for dual power reflected a willingness to give the liberals a chance, since the propertied classes (the liberal Constitutional-Democratic (Kadet) Party became their principal political representative in 1917) had, albeit rather belatedly, rallied to the revolution, or so it appeared. Their adherence to the revolution greatly facilitated its bloodless victory across the vast territory of Russia and at the front. The assumption of power by the soviets in February would have alienated the propertied classes from the revolution, raising the specter of civil war. Besides, workers were not prepared to assume direct responsibility for running the state and the economy.

Their later rejection of dual power and their demand to transfer of power to the soviets were by no means an automatic response to Lenin’s return to Russia and publication of his April theses. Fundamentally, the theses were a recall to the party’s traditional position, but in conditions of world war and a victorious democratic revolution. If Lenin’s position came to prevail, it was because it had become increasingly clear that the propertied classes and their liberal representatives in the government were hostile to the revolution’s goals and wanted, in fact, to reverse the revolution.

As early as the middle of April, the liberal government made clear its support for the war and its imperialist aims. And even before that, the bourgeois press put an end to the brief honeymoon of national unity with its campaign against the workers’ alleged egoism in pursuing their narrow economic interests at the expense of war production. The clear intention was to undermine the worker-soldier alliance that had made the revolution possible.

Not unrelated was the growing suspicion among workers of a creeping lockout, masked as supply difficulties, a suspicion that was amplified by the industrialists’ adamant rejection of government regulation of the faltering economy. Lockouts had long been a favourite weapon of the factory owners. In only the six months preceding the outbreak of war, the capital’s industrialists, in concert with the administration of the state-owned factories, organized no less than three generalized lockouts, in the course of which a total of 300,000 workers were fired. And ten years earlier, in November and December 1905, two general lockouts in the capital had dealt a mortal blow to Russia’s first revolution.

By the late spring and early summer of 1917, prominent personalities of “census society” (the propertied classes) were calling for suppression of the soviets and receiving standing ovations from assemblies of their class. Then in mid-June, under strong pressure from the allies, the provisional government launched a military offensive, putting an end to the de facto cease-fire that had reigned on the eastern front since February.

And so by June, a majority of the capital’s workers had already embraced the Bolsheviks’ demand to free government policy from the influence of the propertied classes. That, in essence, was the meaning of “all power to the soviets”: a government responsible uniquely to the workers and peasants. To that extent, the Bolsheviks, along with most of the capital’s workers, had come to accept the inevitability of civil war.

Defeat of the “July Days”: way forward blocked

But that in itself was not so frightening, since the workers and peasants (the soldiers were overwhelmingly young peasants) were the great majority of the population. Much more worrying was the prospect of civil war within the ranks of the popular classes, within “revolutionary democracy.” For the moderate socialists, the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries (SRs), dominated most of the soviets outside the capital, as well as the Central Executive Committee (TsIK) of soviets and the peasant Executive Committee. And they supported the liberals, to the extent of delegating their leaders to a coalition government, in an effort to shore up the latter’s weak popular authority.

The threat of a civil war within revolutionary democracy was forcefully driven home at the beginning of July, when, together with units of the garrison, the capital’s workers demonstrated massively in order to press the TsIK to take power on its own. They not only failed in that aim, but their demonstrations were marked by the first serious bloodshed of the revolution, followed by a wave of government repressive measures against the left that were condoned by the moderate socialists.

The July Days thus left the Bolsheviks and their worker supporters without a clear way forward. Formally, the party adopted a new slogan that Lenin proposed: power to a “government of workers and the poorest peasants”—with no mention of the soviets, as they were dominated outside the capital by the moderate socialists. Lenin meant that as a call to prepare an insurrection, one that would bypass the soviets, and, if it came to that, even be directed against them. But the slogan was not accepted in practice either by the party or by the capital’s workers, since it meant going against the popular masses who still supported the moderates—and so, civil war within revolutionary democracy.

A particular concern was the attitude of the socialist, that is, left-leaning, intelligentsia, itself a minority of the educated. For the left intelligentsia almost universally supported the moderate socialists. The Bolsheviks were an overwhelmingly plebeian party, and the same was true of the Left Social Revolutionaries, who split off from the SRs (Russia’s peasant party) in September 1917 and formed a coalition soviet government with the Bolsheviks in November. The prospect of having to run the state, and probably also the economy, without the support of educated people was deeply worrying, and in particular to the activists of the factory-committees, overwhelmingly Bolsheviks.

The party base pushes the leadership to insurrection

General Kornilov’s abortive uprising at the end of August, which had the enthusiastic support of the propertied classes, appeared initially to open a way out of the impasse. In face of the obvious, the moderate socialists seemed to accept the necessity of a break with the liberals. (The liberal ministers had resigned on the eve of the uprising). The workers reacted to news of Kornilov’s march on Petrograd with a curious mixture of relief and alarm. They were relieved that they could at last take action against the advancing counterrevolution—and they did so with great energy—in unison with, and not against, the rest of revolutionary democracy. Lenin, following Kornilov’s defeat, offered the TsIK his party’s support, to the extent of acting as a loyal opposition, if it would take power.

But after some brief wavering, the moderate socialists refused to break with the propertied classes. They allowed Kerensky to form a new coalition government, which included some particularly odious bourgeois personalities, such as industrialist S.A. Smirnov, who had only recently locked out the workers of his textile mills.

But by the end of September, the Bolsheviks already had majorities in most of the soviets throughout Russia and so could count on a majority at the Congress of Soviets, grudgingly set by the TsIK for October 25. Still in hiding from an arrest order, Lenin demanded that his party’s central committee prepare an insurrection. But the central committee’s majority hesitated, preferring to await a constituent assembly. And one can understand their hesitation. After all, an insurrection would unleash the still largely latent civil war. It was a terrifying leap into the unknown that would place on the party the responsibility for governing in conditions of deep economic and political crisis. On the other hand, the hope that a constituent assembly could overcome the profound polarization that characterized Russian society or that the propertied classes would accept its verdict, if it went against them, was certainly an illusion. And in the meanwhile, industrial collapse and mass hunger were fast approaching.

If the Bolshevik leadership decided to organize an insurrection, it was not because of Lenin’s personal authority, but rather under pressure from the middle and lower ranks of the party, to whom Lenin had been appealing. The party organization in Petrograd numbered 43,000 members in October 1917, of whom 28,000 were workers (in a total industrial work force of some 420,000), and 6000 were soldiers. And these workers were ready to act.

The mood among the mass of workers outside the party, was, however, more complex. They strongly supported the demand to transfer power to the soviets. But they were not about to take the initiative themselves. This was a marked reversal from the first five months of the revolution, when the worker rank and file had held the initiative and compelled the party to follow. It had been so in the February Revolution, in the April protests against the government’s war policy, in the movement for workers’ control, aimed at forestalling a creeping lockout, and in the July demonstrations aimed at pressuring the TsIK to take power.

But the bloodshed in the July Days and the repression that followed had changed things. True, the political situation had since evolved, to the point that the Bolsheviks almost everywhere stood at the head of the soviets. But in the days preceding the insurrection, the entire non-Bolshevik press was confidently predicting an even bloodier defeat of an insurrection than the workers had suffered in the July Days.

Another source of the workers’ hesitation was the looming specter of mass unemployment. The advancing industrial collapse was the most potent argument in favour of immediate action. But it was also a source of insecurity that made workers hesitate.

The initiative, therefore, fell to the party. And it was not as if Bolshevik workers were themselves free of doubt. But they had certain qualities, forged over the years of intense struggle against the autocracy and the industrialists, that allowed them to overcome it. One of these qualities was their aspiration to class independence from the bourgeoisie, which was also the defining trait of Bolshevism as a workers’ movement. In the pre-revolutionary years that aspiration had expressed itself in these workers’ insistence that their organizations, be they political, economic or cultural, remain free of the influence of the propertied classes.

Closely related to that was these workers’ strong sense of dignity, both as individuals and as members of the working class. The concept of a “conscious worker” in Russia embraced an entire world view and moral code that were separate from, and largely opposed to, those of census society. The sense of dignity manifested itself, among other ways, in the demand for “polite address,” that invariably figured in lists of workers’ strike demands. It was a demand to be addressed by management in the polite second person plural, rather than the informal singular, reserved for close friends, children and underlings. In its compilation of strike statistics, the Tsarist Ministry of Internal Affairs put “polite address” in the column of political demands, presumably because it implied a rejection of the workers’ subordinate position in society. In 1917, resolutions of factory meetings in 1917 often referred to the provisional government’s policies as a “mockery” of the working class. And in October, when the workers’ red guards refused to bend over while running or to fight lying down, since they considered that a display of cowardice and a disgrace for revolutionary workers, the soldiers had to explain to them that there is no honour in offering one’s forehead to the enemy. But if the sense of class honour was a military liability, it is unlikely there would have been an October Revolution without it.

October—a popular revolution

Although the initiative fell largely to the party members in October, the insurrection was welcomed by virtually all the workers, even by most of the printers, traditionally supporters of the Mensheviks. But the question of the composition of the new government arose at once. All the workers’ organization, by then headed by Bolsheviks, and the Bolshevik party organization itself, called for a coalition government of all the socialist parties.

Once again, this expressed the concern for unity of revolutionary democracy and the desire to avoid civil war within its ranks. In the Bolshevik central committee, Lenin and Trotsky were opposed to including the moderate socialists (but not the Left SRs and Menshevik-Internationalists), considering that they would paralyze the government’s action. But they stood aside, while the negotiations proceeded.

That coalition, however, was not to be. Talks soon broke down over the issue of soviet power: the Bolsheviks, and the vast majority of workers, wanted the government to be responsible to the soviets—that is, a popular government free of the influence of the propertied classes. The moderate socialists, however, considered the soviets too narrow a basis for a viable government. They continued to insist, albeit in somewhat masked form, on the inclusion of representatives of the propertied classes, or, at least, of the “intermediate strata” not represented in the soviets. But Russian society was deeply divided, and the latter, including most of the intelligentsia, were aligned with the propertied classes. More to the point, the moderates refused any government with a Bolshevik majority, even though the Bolsheviks had been the majority at the Congress of Soviets that voted to take power. In essence, the moderates were demanding to annul the October insurrection.

Once that became clear, the workers’ support for a broad coalition evaporated. Soon afterwards, the Left SRs, who reached the same conclusion as the workers, formed a coalition government with the Bolsheviks. Toward the end of November, a national peasant congress, in which the Left SRs dominated, decided to merge its executive committee with the TsIK of workers’ and solders’ deputies, a decision that was met with relief and jubilation in the Bolshevik party and by workers generally: unity had been achieved, at least from below, although without the left intelligentsia, aligned in its majority with the moderate socialists. (It should be noted, however, that the Mensheviks, unlike the SRs, did not take up arms against the soviet government.)

This, then, is the meaning of “they dared,” as the legacy of October. The Bolsheviks, as a genuine workers’ party, acted according to the maxim “Fais ce que dois, advienne que pourra” (Do what one must; happen what will), which, in Trotsky’s view, should guide revolutionaries in all great struggles of principle.3 But I have tried to show that the challenge was not accepted lightly. The Bolsheviks were not adventurists. They feared civil war, tried to avoid it, and, if that was not possible, at least to limit its severity and improve the odds.

The responsibility of those who refuse to dare

In an essay written in 1923, the Menshevik leader, Fedor Dan, explained his party’s refusal to break with the propertied classes even after Kornilov’s uprising. It was because the “middle strata,” that part of “democracy” not represented in the soviets (Dan mentions a teacher, a co-operator, the mayor of Moscow…) would not countenance a break with the propertied classes—they were convinced that the country could not be governed without them. And they would not even consider participating in a government with Bolsheviks. Dan continued:

Then—theoretically!—there remained only one path for an immediate break with the coalition [with representatives of the propertied classes]: the formation of a government with Bolsheviks—one not together with ‘non-soviet’ democracy [the ‘middle strata’], but against it. We considered that path unacceptable, given the position that the Bolsheviks were adopting by the time. We understood clearly that to enter onto that path meant to enter onto the path of terror and civil war, to do everything that the Bolsheviks were, in fact, later forced to do. None of us felt it possible to assume responsibility for such a policy of a non-coalition government.4

Dan’s position can be contrasted with that of another moderate socialist, the SR V.B. Stankevich, a rare figure in his party (who had been a commissar at the front under the provisional government). In a letter from February 1918 to his party comrades, he wrote:

We have to see that by this time the forces of the popular movement are on the side of the new regime …

There are two paths open to them [the moderate socialists]: pursue their irreconcilable struggle against the government, or peaceful, creative work as a loyal opposition …

Can the former ruling parties say that they have by now become so experienced that they can manage the task of running the country, a task that has become not easier, but harder? For, in essence, they have no programme to oppose to that of the Bolsheviks. And a struggle without a programme is nothing better than the adventures of Mexican generals. And even if the possibility of creating a programme existed, you have to understand that you don’t have the forces to carry it out. For to overthrow Bolshevism you need, if not formally, then at least in fact, the united efforts of everyone, from the SRs to the extreme right. But even in those conditions, the Bolsheviks are stronger…

There is but one path: the path of a united popular front, united national work, common creativity…

And so what tomorrow? To continue the pointless, meaningless and in essence adventurist attempts to seize power? Or to work together with the people in realistic efforts to help it to deal with the problems that face Russia, problems that are linked to the peaceful struggle for eternal political principles, for genuinely democratic bases for governing the country!5

I will let the reader decide which position, Dan’s or Stankevich’s, had more merit. But one can make a convincing argument that the moderate socialists’ refusal “to dare” contributed to the outcome that they claimed so to fear.

History since October 1917 is replete with examples of left parties that did not dare, when they should have. One can mention, among others, the German Social Democrats in 1918, the Italian Socialists in 1920, the Spanish left in 1936, the French and Italian Communists in 1945 and 1968-69, the Chilean Unidad Popular in 1970-73, most recently Syriza in Greece. The point, of course, is not that they failed to organize an insurrection at some particular moment, but rather that they refused from the very outset to adopt a strategy whose goal was to wrest economic and political power from the bourgeoisie, a strategy that necessarily requires, at some point, a revolutionary break with the capitalist state.

Today, when the alternatives facing humanity are so deeply polarized, when, more than ever, the only real options are socialism or barbarism, when the future of civilized society itself is at stake, the left should take inspiration from October. That means, despite the historic defeat suffered by the working class and allied social forces over the past decades, to reject as illusory the goal of restoring the Keynesian welfare-state, a return to “genuine social democracy.” For such a programme in contemporary capitalism is bound to fail and further demobilize. To dare today means to develop a strategy whose end-goal is socialism and to accept that that goal will necessarily involve, at one point or another, a revolutionary break with the economic and political power of the bourgeoisie, and so with the capitalist state.

Notes

- ↩ This article is based in large part on my The Petrograd Workers in the Russian Revolution, Brill-Haymarket, Leiden and Boston, 2017.

- ↩ K. Marx, “Afterword to the Second Edition” of Capital vol. I, International Publishers, N.Y., 1967, p. 17.

- ↩ Trotsky, L., My Life, Scribner, N.Y., 1930, p. 418.

- ↩ F. I., Dan, “K istorii poslednykh dnei Vremennogo pravitel’stva,” Letopis’ Russkoi Revolyutsii, vol. 1, Berlin, 1923.

- ↩ I. B. Orlov, “Dva puti stoyat perednimi …” Istoricheskii Arkhiv, 4, 1997, p. 79.