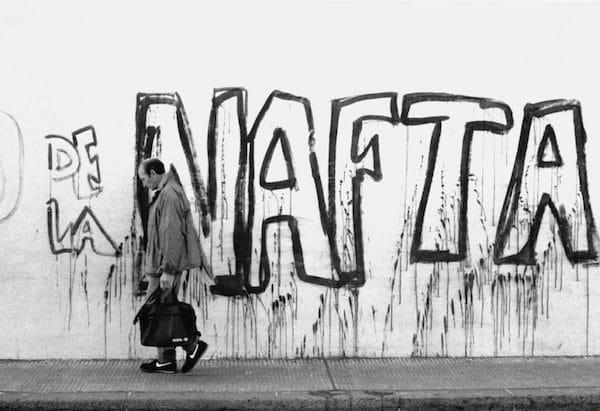

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is unpopular with many working people in the United States, who correctly blame it for encouraging capital flight, job losses, deindustrialization, and wage suppression. President Trump has triggered the renegotiation of the agreement, which will likely conclude early next year. Unfortunately, progressives are in danger of missing an important opportunity to build a working class movement for meaningful economic change. By refusing to openly call for termination of the agreement, they are allowing President Trump to present himself as the defender of the US workers, a status that will likely help him secure the renewal of the treaty and a continuation of destructive globalization dynamics.

The NAFTA debate

According to a recent poll commissioned by Public Citizen:

At a time of great peril for our democracy and deepening public opposition to Donald Trump on many fronts, he wins high marks from voters on handling trade and advocating for American workers: 46 percent approve of his handling of trade agreements with other countries, 51 percent, his ‘putting American workers ahead of the interests of big corporations’ and 60 percent, how he is doing “keeping jobs in the United States.”

This perception of Trump’s advocacy for workers is encouraged by media stories of the strong opposition by leading multinational corporations to several of President Trump’s demands for changes to the existing NAFTA agreement.

The most written about and controversial proposals include:

- Major modifications to NAFTA’s investor-state dispute settlement system, which allows foreign investors to sue host governments in secret tribunals that trump national laws if these investors believe that government actions threaten their expected profits. The Trump administration proposes to change this system by (1) establishing an “opt-in” provision that would make participation voluntary and (2) ending the ability of private investors to use claims of denial of “minimum standard of treatment” or an “indirect expropriation” as grounds for filing a claim.

- A tightening of the rules on the origins of car parts. NAFTA rules govern the share of a product that must be sourced within NAFTA member countries to receive the agreement’s low tariff benefits. The Trump administration wants to raise the auto rules of origin to 85 percent from the current 62.5 percent and include steel as one of the products to be included in the calculations. It has also proposed adding a new US-only content requirement of 50 percent.

- The introduction of a NAFTA sunset clause that would allow any of the participating countries to terminate the deal after five years, a clause that could well mean a renegotiation of the agreement every five years.

- The end to government procurement restrictions on preferential treatment for domestic firms, which would free the US government to pursue its touted “Buy American” agenda.

Canadian and Mexican government trade representatives have publicly rejected these proposals. The US corporate community has called them “poison pills” that could doom the renegotiating process, possibly leading to a termination of the agreement. The president of the US Chamber of Commerce has said that:

All of these proposals are unnecessary and unacceptable. They have been met with strong opposition from the business and agricultural community, congressional trade leaders, the Canadian and Mexican governments, and even other U.S. agencies.… The existential threat to the North American Free Trade Agreement is a threat to our partnership, our shared economic vibrancy, and clearly the security and safety of all three nations.

Corporate lobbyists are hard at work, trying to convince members of Congress to use their influence to get Trump to withdraw these proposals, but so far with little success. In fact, the Trump administration has pushed back:

In remarks to the news media in mid-October, Robert E. Lighthizer, the United States trade representative, said that businesses should be ready to forego some of the advantages they receive under NAFTA as the United States seeks to negotiate a better deal for workers. In order to win the support of people in both parties, businesses would have to “give up a little bit of candy,” he said.

It is this kind of public back and forth between corporate leaders and the Trump administration that has encouraged many working people to see President Trump as sticking up for their interests. In broad brush, workers do not trust a dispute resolution settlement system that allows corporations to pursue profits through secret tribunals that stand above national courts. They also welcome measures that appear likely to force multinational corporations to reverse their past outsourcing of jobs, especially manufacturing jobs, and promote “Buy American” campaigns. And, they have no problem with periodic reviews of the overall agreement to allow for ongoing corrections that might be needed to improve domestic economic conditions.

The rest of the story

Of course, NAFTA negotiations are not limited to these few contentious issues. In fact, trade negotiators have made great progress in reaching agreement in many other areas. However, because of the lack of disagreement between corporations and the Trump administration on the relevant issues, the media has said little about them, leaving the public largely ignorant about the overall pace and scope of the renegotiation process.

Perhaps the main reason that agreement is being reached quickly on many new issues is because many of the Trump administration’s trade proposals closely mirror those previously agreed to by all three NAFTA country governments during the Transpacific Partnership negotiations. These include “measures to regulate treatment of workers, the environment and state-owned enterprises” as well as “new rules to govern the trade of services, like telecommunications and financial advice, as well as digital goods like music and e-books.” In short, taken overall, it is clear that the Trump administration remains committed to “modernizing” NAFTA in ways designed to expand the power and profitability of transnational corporations.

A case in point is the proposed change to the existing NAFTA side-agreement on labor rights. NAFTA currently includes a rather useless side agreement on labor rights. It only requires the three governments to enforce their own existing labor laws and standards and limits the violations that are subject to sanctions. For example, sanctions can only be applied—and only after a long period of consultations, investigations, and hearings–to violations of laws pertaining to minimum wages, child labor, and occupational safety and health. Violations of the right to organize, bargain collectively, and strike are not subject to sanctions.

The labor standards agreement that the US proposes to include in NAFTA is one that it has used in more recent trade agreements and was to be part of the Transpacific Partnership. It says that “No Party shall fail to effectively enforce its labor laws through a sustained or recurring course of action or inaction in a manner affecting trade or investment between the Parties, after the date of entry into force of this Agreement for that Party.”

This labor agreement is included in the US-Dominican-Central American Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) and we now have an example of how it works, thanks to a case filed in 2011 by the US against Guatemala. The panel chosen to hear the case concluded, in June 2017, that the US “did not prove that Guatemala failed to conform to its obligations.” The reason: the three person panel made its own monetary calculations about whether Guatemalan labor violations were serious enough to affect trade or investment flows between the two countries and decided they were not.

As Sandra Polaski, former Deputy Director-General for Policy of the International Labor Organization, writes:

The panel reached its decision that Guatemala had not breached its obligations under the DR-CAFTA because the violations had not occurred “in a manner affecting trade” between the parties.… The panel chose to establish a demanding standard in its interpretation of that phrase, requiring that a complaining country would have to prove that there were cost savings from specific labor rights violations and that the savings were of sufficient scale to confer a material competitive advantage in trade between the parties. This threshold is unprecedented in any analogous applications: WTO panels have interpreted similar language much more narrowly, as affecting conditions of competition, without requiring demonstration of costs and their effects. Demonstrating changes in costs at this level would require access to sensitive internal company accounts (at a minimum), and the perpetrators of labor violations would likely have hidden them in any case. This standard could not be met without subpoena power, which does not exist under the trade agreements.…

The decision is disturbing for multiple reasons: because of the injustice toward the affected Guatemalan workers; because it invalidated the parties’ explicit commitment to broad enforcement of labor rights contained both in the obligatory commitments and the overall stated purposes of the agreement; and because as the first and as of now only arbitration arising from a labor clause (or environmental clause) it set a precedent for future cases.

In short, labor exploitation is likely to continue unchecked under a possible new NAFTA, which can be expected to remain as corporate friendly as the original agreement.

The need for a new progressive strategy of opposition

President Trump has threatened to withdraw the US from NAFTA if the other two countries do not agree to his demands for key NAFTA changes, in particular to the investor-state dispute settlement system and rules on the origins of car parts, the inclusion of a sunset clause, and an end to government procurement restrictions. While we cannot predict the future, the odds are great that compromises will be reached on these issues, allowing President Trump to present a renegotiated NAFTA as a win for working people.

As Jeff Faux, founder of the Economic Policy Institute, comments:

The erratic and belligerent Trump might, of course, drive US-Mexican relations over a cliff. But he prides himself as a deal-maker, not a deal-breaker. So the most likely outcome is a modestly revised NAFTA that: 1) Trump can boast fulfills his pledge 2) Peña Nieto can use to claim that he stood up to the bullying gringo 3) doesn’t threaten the low-wage strategy for both countries that NAFTA represents.

Revisions might include weakening NAFTA’s dispute settlement courts, raising the minimum required North American content for duty-free goods, and reducing the obstacles to cross-border trade for small businesses on both sides of the border.

Changes like this could marginally improve the agreement, and would be acceptable to the Canadians, who have been told by Trump that he is not going after them. But from the point of view of workers in the American industrial states who voted for Trump, the new NAFTA is likely to be little different from of the old one. The low-wage strategy underlying NAFTA that keeps their jobs drifting south and US and Mexican workers’ pay below their productivity will continue.

But you can bet that Trump will assure them that it is the greatest trade deal the world has ever seen.

Sadly, the progressive movement has pursued the wrong strategy to build the kind of movement we need to oppose the likely NAFTA renewal or take advantage of a possible US withdrawal. In fact, it has largely allowed President Trump to shape the public discussion around the renegotiations.

To this point, progressive trade groups, labor unions, and Democratic Party politicians have refrained from calling Trump’s bluff and demanding termination of the agreement, despite the fact that this and other so-called free trade agreements are not really reformable in a meaningful pro-worker sense. Instead, they have concentrated on demonstrating the ways that NAFTA has harmed workers, highlighting areas that they think are in most need of revision and offering suggestions for their improvement, and mobilizing their constituencies to press the US trade representative to adopt their desired changes. Progressive trade groups have generally turned their spotlight on the investor-state dispute resolution system and outsourcing, as have Democratic Party politicians. Trade unions, for their part, have emphasized outsourcing and labor rights.

Significantly, these are all areas, with the exception of labor rights, where the Trump administration has put forward proposals for change which if realized would go some way to meeting progressive demands. The result is that the progressive movement appears to be tailing or reinforcing Trump’s claims to represent popular interests. And, by focusing on targeted issues, the movement does little to educate the population about the ways in which the ongoing negotiations are creating new avenues for corporations to enhance their mobility and profits, especially in services, finance, and e-commerce.

Apparently, leading progressive groups plan to wait until they see the final agreement and then, if they find it unacceptable with regards to their specific areas of concern, call for termination of the agreement. But this wait and see strategy is destined to fail, not only to build a movement capable of opposing a revised NAFTA agreement, but even more importantly to advance the creation of a working class movement with the political awareness and vision required to push for a progressive transformation of US economic dynamics.

For example, this strategy of creating guidelines for selective changes in the agreement tends to encourage people to see the government as an honest broker that, when offered good ideas, is likely to do the right thing. It also implies that the agreement itself is not a corporate creation and that a few key changes can make it an acceptable vehicle for advancing “national” interests. Finally, because agreements like NAFTA are complex and hard to interpret it will be no simple matter for the movement to help its various constituencies truly understand whether a renegotiated NAFTA is better, worse, or essentially unchanged from the original, an outcome that is likely to demobilize rather than energize the population to take action. Of course, if Trump actually decides to terminate the agreement, the movement will be put in the position of either having to praise Trump or else criticize him for not doing more to save NAFTA, neither outcome being desirable.

There is, in my opinion, a better strategy: engage in popular education to show the ways that trade agreements are a direct extension of decades of domestic policies designed to break unions and roll back wages and working conditions, privatize key social services, reduce regulations and restrictions on corporate activity, slash corporate taxes, and boost multinational corporate power and profitability. Then, organize the most widespread movement possible, in concert with workers in Mexico and Canada, to demand an end to NAFTA. Finally, build on that effort, uniting those fighting for a change in domestic policies with those resisting globalization behind a campaign directed at transforming existing relations of power and creating a new, sustainable, egalitarian, and solidaristic economy.

It is not too late to take up the slogan: just say no to NAFTA!