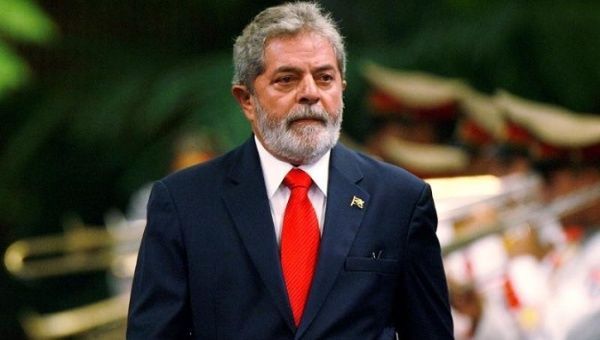

In an exclusive interview with teleSUR, Brazilian professor and researcher Sabrina Fernandes discusses former President Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva’s Jan. 24 corruption trial and forthcoming elections in the South American country.

What has been the response of the non-Workers’ Party, PT, left to the current situation and in the lead up to the presidential election?

The non-PT left is divided between the organizations in the left that were part of the PT governments and its base, and the left that has stood in a critical stance of the governments, pushing for a more radical agenda.

The first is standing together with Lula throughout the sentencing and appeal process and part of it supports him as their preferential candidate, with the notable exception of Manuela D’Avila, from the Communist Party of Brazil, PCdoB. The opposition left, which I call the radical left, is a very fragmented one, so its own positions are also fragmented.

Most of the Socialism and Liberty Party, PSOL, internal organizations are standing in solidarity with Lula for his right to be a candidate, which depends on a successful appeal, although the PSOL will have its own presidential candidate. Other parties such as the Unified Socialist Workers’ Party, PSTU, and the Brazilian Communist Party, PCB, have kept a wider distance from the troubles afflicting the PT, and it’s noteworthy that the PSTU promoted a “Out with all of them!” campaign during the former President Dilma Rousseff impeachment crisis and they are urging the working class to organize against President Michel Temer’s reforms, rather than focusing on the trial.

Lula has been working his way through the country on his caravan. Do you think this has had impact? If so, what?

In some ways, yes.

Lula is a very well liked public personality in many parts of the country, despite the years of character assassination promoted by the mainstream media. Even leftist critics who have stood in fierce opposition to his policies tend to acknowledge him as a savvy politician and widely popular former president.

The caravan helped to remind some of the former Lula base that he is still a powerful contender and kept his name in the headlines through positive media frames in contrast to the investigation and trial reports. In the event that Lula is cleared and becomes, officially, a presidential candidate, the caravan will have served the purpose of paving the way for a campaign.

However, in terms of the trial, I don’t believe it was that paramount to build a supporter base to stand with him in Porto Alegre. Most of the protesters joining him in solidarity against the charges are connected to the organized left, especially sectors that have supported Lula from the beginning.

In the event of Lula not being able to run in 2018, what does the race look like?

The race will be very polarized between the left and the right, but it will face a far more fragmented electoral left than in the past 30 years because there is no other name in the left with the stature of Lula’s name.

A conviction may also act in detriment of the PT candidate that replaces him, as well as explicit endorsement by the former president. There is much speculation about who the PT would promote instead, but no obvious name given that their sole efforts have been on guaranteeing Lula’s appeal so that he can be the candidate.

It’s important to say that the electoral right is also very fragmented in 2018, with direct disputes inside of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, PSDB, the PT’s traditional right-wing opponent in the federal elections, and names like Jair Bolsonaro push the spectrum to the extreme right. While Bolsonaro presents a definite setback, the fragmentation inside the right ensures that his support is limited, especially since he is controversial and hasn’t managed to gather enough support from the markets and main representatives from the elites in Brazil, who we know influence the media and the electability of a candidate.

Does the PT have a contingency? Is there a plan B for pro-Lula/PT social movements like some of the unions and the Landless Workers’ Movement, MST?

If Lula is convicted, he can still be the PT’s presidential candidate up to the point where the Superior Electoral Court also finds him guilty through the Ficha Limpa law and prevents him from running.

It’s my guess that the party will keep Lula on the race as long as possible and that, once the Ficha Limpa process is concluded, they will replace him with a different candidate. This will allow the PT to try to build support for Lula as an endorser and to keep the party in the headlines.

It will be the task of the PT and the organizations that support it to take this time to find a new candidate and build their name as well. At the same time, with a conviction that results from such a flawed process — from the investigations to Moro’s sentencing — Lula may become a bit of a martyr, representing the elites’ prosecutorial approach to the left in general and the interests of the people.

Even if the PT government’s are seen as not having applied a sufficient amount of meaningful reforms, there is little doubt that the reforms since Temer became president have been devastating and despite this, from the outside, it appears as though the right-wing is strengthened. Is this the case from your perspective? What is the best outcome of the election for the left and popular sectors?

What is worrisome is that positive electoral results for the left in 2018 do not necessarily guarantee that the Temer’s reforms will be done away with. Lula himself made some controversial remarks last year about having keep some of the reforms, while the PT’s national president recently stated that Lula ought to prepare another version of is 2002 letter to the markets in order to appease them.

This is a trend for most of the candidates in the the center-left and all of the candidates in right, which has put the radical left is the position of being as intransigent as possible when it comes to repealing the reforms and promoting progressive ones instead. The radical left is still very small in comparison, though, and, as of now, it doesn’t hold the ingredients for a Bernie Sanders phenomenon that could tip the electoral scales in favour of the left in 2018.

A lot of the worries in the left, in general, is that the right may return officially to power in 2019, which would prove even more disastrous than the Temer illegitimate mandate. What we must hope for is that the left manages to present itself in all of its diversity in a way that sounds like the real alternative for those suffering from the economic crisis and the deep inequalities that plague Brazil.

Even if there are multiple candidates in the left rather than consensus around one name and one project, the best outcome would be one that gets the popular sectors to the streets again around real change, pushing for a more radical leftist agenda and for parties to show strength and courage to implement what the PT governments failed to do. Ideally, that would result in a leftist elected president and a more progressive National Congress, considering that much of what has happened so far against working class interests is due to the power of a right-wing Congress in Brazil.

Sabrina Fernandes has a PhD in Sociology and currently teaches and researchers at the University of Brasília. She is the author of a number of pieces on leftist praxis and fragmentation in Brazil, which is the principal subject of her research, and the researcher and host of the YouTube channel Tese Onze on politics and sociology.