November 2017 marked the centenary of two of the most decisive events in the twentieth century: the Bolshevik-led revolution in Russia and the Balfour Declaration in Britain. The Russian Revolution was executed by the Bolsheviks in the name of peace and international socialism; the Balfour Declaration was a British government commitment to support a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. This was not simply a remarkable coincidence. At loggerheads were two mutually exclusive political objectives: the one to promote worldwide, anti-imperialist revolution; the other, to further British imperial interests in the Middle East.

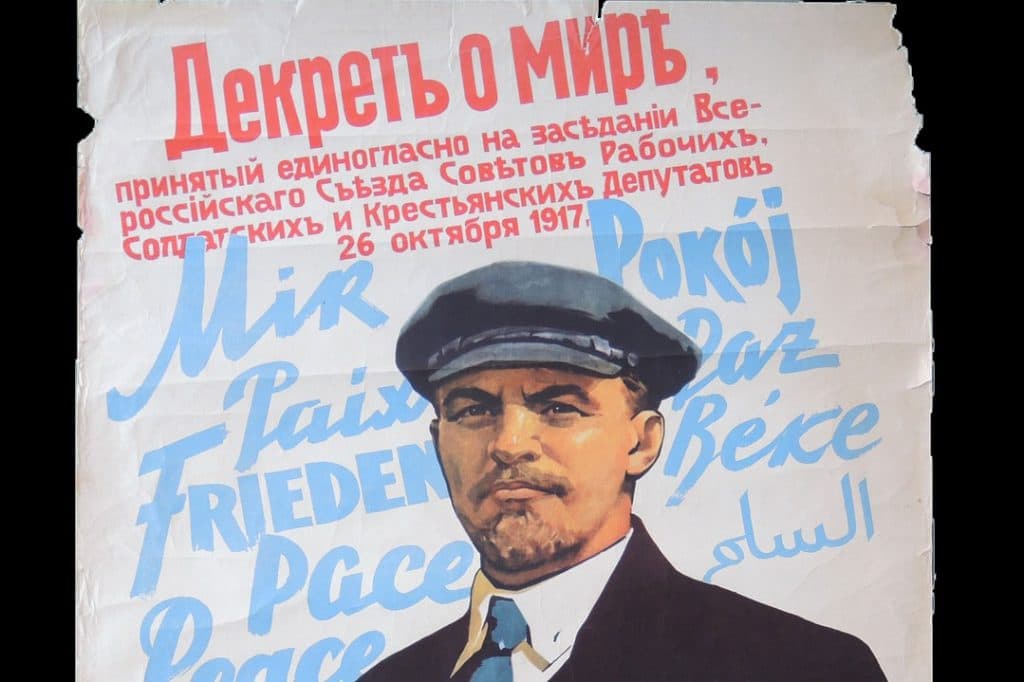

The Bolsheviks rode to power on the back of an armed insurrection in Petrograd on November 7, 1917 (October 25 in the old Russian calendar). Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin immediately declared: “We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order.” Two days later the fledgling Workers’ and Peasants’ Government issued its famous first decree: “The Decree on Peace,” which amidst the carnage of the First World War called for

A just and democratic peace…an immediate peace without annexations (i.e., without the seizure of foreign territory and the forcible annexation of foreign nationalities) and without indemnities.

The Balfour Declaration was a letter dated November 2, 1917 from British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. Published on the very same day as Lenin’s “Decree on Peace,” it read:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

The Balfour Declaration had been in the making for some time. Indeed, in 1916, the same year that the infamous Sykes-Picot agreement secretly planned to divide up a post-war Middle East between Britain, France and Tsarist Russia, Balfour, then First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to then head of the General Zionist Council, Chaim Weizmann: “You know Dr Weizmann, if the Allies win the war you may get your Jerusalem.”1 The published version of the Balfour Declaration was actually watered down from that which had originally been approved by British Prime Minister Lloyd George and the Foreign Office. It had proposed that all of “Palestine should be reconstituted as the national home of the Jewish people.”2

Not surprisingly, there is considerable contention about Britain’s motivation in making the Balfour Declaration. One school of thought, not without basis, has emphasized British concerns about the outbreak of Revolution in Russia in February/March 1917 which threatened the British-French-Russian Entente war effort against Germany and its allies. In this perspective, the only important motive behind the Balfour Declaration was to give Jews in Russia, whom it was presumed had decisive political influence in revolutionary Russia, an incentive to oblige the Provisional Government to continue to wage war on the side of the Entente. There is certainly evidence that for some British officials involved in the development of the Balfour Declaration the revolutionary situation in Russia by October 31, 1917 was a major consideration.3 As an unnamed British high official stated at the time: “A pity our Declaration did not come four months earlier. It might have made all the difference in Russia.”4 Behind this perspective was the assumption, rooted in the anti-Semitism which pervaded the thinking of Britain’s conservative political elites at the time, that Jews in Russia were part of a powerful collective entity: Zionists and extreme revolutionaries who were spreading harmful pacifist propaganda.

Undoubtedly, British anxiety in 1917 that Russia continue fighting Germany and its allies was a consideration in wooing Russian Zionists but it should not be viewed in isolation from Britain’s imperial ambitions in the Middle East.5 Emblematic of this was the outlook of Winston Churchill, who combined pro-Zionism with visceral anti-Bolshevism. As early 1908, then Member of Parliament Churchill had assured a leader of the Jewish community in his local constituency of Manchester that “Jerusalem must be the ultimate goal.”6 By 1920, Churchill, by then War and Air Minister and chief proponent of British intervention in the Russian Civil War against the Bolshevik Red Army, saw Zionism as both a powerful antidote to Bolshevism and as an instrument for securing British interests in the Middle East; above all in Palestine.

“Zionism Versus Bolshevism”

In a 1920 newspaper article melodramatically entitled “Zionism Versus Bolshevism. A Struggle for the Soul of The Jewish People,” Churchill expounded his perspective on the Jews.7 It was replete with racialized, anti-Semitic stereotypes common among British Tories. Distinguishing between “Good and Bad Jews,” Churchill opined that “It would almost seem as if…this mystic and mysterious race had been chosen for the supreme manifestations, both of the divine and the diabolical.”

Continuing in this crude, racist vein, Churchill identified three categories of Jews, two of whom he obviously put in the “good” category: First, were the “‘National’ Jews…who…while adhering faithfully to their own religion, regard themselves as citizens” of a country. Second, were the “International,” “terrorist” Jews. These were the “sinister” Bolsheviks who had fomented the Russian Revolution: “With the notable exception of Lenin,” he observed, “the majority of the leading figures [Trotsky, Zinoviev, Radek] are [atheistical] Jews.” Third were the Zionists, whom he saw as a formidable antidote to Bolshevism: “Zionism…has already become a factor in the political convulsions of Russia, as a powerful competing influence in Bolshevik circles with the international communistic system.”

Churchill called on the “national Jews” to join with the Zionists to “combat” the “Bolshevik conspiracy.” For this reason, he endorsed not just a Jewish “home” in Palestine but the Zionist project for a Jewish “state” “by the banks of the Jordan” River: “A Jewish State [of three or four million Jews] under the protection of the British Crown,” he declared, could thwart Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs Leon Trotsky’s alleged “schemes of a world-wide communistic State under Jewish domination.” For the imperial warlord Churchill, the stakes were very high: The contest between “Zionist and Bolshevik Jews” was nothing “less than a struggle for the soul of the Jewish people.”

War on “secret diplomacy”

Notwithstanding Churchill’s hyperbolic rhetoric, in reality at stake was a struggle for British imperial domination and exploitation of the colonial world that was imperiled by the Bolshevik Revolution. On November, 22 1917, barely a fortnight after the Bolsheviks had come to power, Trotsky had put forward diplomatic “proposals for a truce and a democratic peace without annexation and without indemnities, based on the principle of the independence of nations, and of their right to determine the nature of their own development themselves.” The very next day, Trotsky declared war on “secret diplomacy,” publishing in Pravda and Izvestia, the newspapers of the Bolshevik Party and Soviet government respectively, the hitherto secret Sykes–Picot Agreement to carve up the dying Ottoman Empire. This agreement was a British betrayal of the Arabs, whom the British had promised independence in the 1915 McMahon-Hussein correspondence in return for Arab military support in the war against the dying Ottoman Empire–Germany’s Middle East ally. In his war “war on ‘secret diplomacy’,” Trotsky was indeed the Julian Assange of his time. Furthermore, in December 1917 the Bolsheviks added fuel to anti-imperialist fire by calling on the Muslims of the Middle East and Asia as a “holy task” to “overthrow the imperialist robbers and enslavers.” There is no doubt that the Bolsheviks’ unqualified support for colonial national self-determination was a threat to the determination of the victorious World War powers to re-establish their colonial hegemony. Where 1919 Versailles Peace treaties provided for selective self-determination or none at all in the colonial world, Lenin’s “Decree on Peace” universalized this principle.8 For Churchill and his ilk, the Bolsheviks were the spoilers of the imperial world system.

British imperial motivations

Notwithstanding Britain’s fear of the Bolshevik Revolution, London’s primary motivation in championing the Zionist cause in Palestine was its immediate interests in the Middle East, which preceded the revolution. A Jewish state in Palestine, Churchill categorically declared in his February 1920 article, would be “in harmony with the truest interests of the British Empire.” Already, in 1916, British Prime Minister Lloyd George had privately declared his first priority was to obtain sole British suzerainty of Palestine, notwithstanding ostensible commitments to his French allies. Palestine would be invaluable as a bulwark to reinforce British rule in Egypt, which it had occupied in 1882, thereby securing the Suez Canal as a key conduit to British India, still the “jewel in the British crown.”

A British pro-Zionist declaration had a number of advantages in furthering this strategic objective. Firstly, it would impede Germany establishing its own relationship with the Zionists, although the Zionists insisted Britain should be their sole agent in the Middle East. Secondly, but more importantly, a British pro-Zionist declaration was needed to circumvent the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement to prevent the French from obtaining the part of Palestine that had been promised to them in that agreement. Lloyd George and Sir Mark Sykes had both agreed that a promise to the Zionists could mask British aspirations for a post-war protectorate over Palestine in order to avoid a confrontation with French, thereby imperiling the Entente.9 To that end, on August 14, 1917 Sykes had suggested that the solution to the problems posed by opponents to the goal of sole British suzerainty of Palestine was “to get Great Britain appointed trustee of the Powers for the administration of Palestine.” Clearly, there was no honor among imperial thieves!

Anglo-American relations

A Third consideration for Britain, in light of U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s opposition to annexation, was the need to placate American sensibilities over the issue of Palestine. Britain was convinced that only U.S. military might could win the war against Germany, which the U.S.A had entered on April 1917. However, this also increased British dependence on the U.S. which would strengthen the hand of Wilson. For Lord Balfour, the importance of a declaration lay in the pro-British propaganda it could create among Zionists in both America and Russia. This would have several benefits for Britain. First, given that by 1917 Britain was militarily and financially dependent on the U.S., influencing American Zionists could ameliorate this humiliating dependence. Second, in line with prevailing conservative prejudices, the British Foreign Office believed that American Jews were very influential and pro-Zionist: a declaration in favor of Zionist aspirations would mean that they were more likely to espouse British interests in Washington. Third, British suzerainty over Palestine could be masked as Jewish “self-determination” thereby placating both Woodrow Wilson and the French.10

On October 31, 1917, the British War Cabinet finally agreed on what came to be called “The Balfour Declaration.” It was quickly reinforced by British boots on the ground: on December 9, 1917, British Imperial forces under General Edmund Allenby took Jerusalem from their German commanded Ottoman counterparts. In these circumstances, Jewish “self-determination” became a diplomatic fig leaf for British force majeure in Palestine, which, based on British belief in the collective power of world Jewry, Zionist influence would facilitate. Sykes himself made this quite clear in a memorandum penned on March 3, 1918:

The important point to remember is that through Zionism we have a fundamental world force behind us that has enormous influence now, and will wield a far greater influence at the peace conference. If we are to have a good position in the Middle East after the war, it will be through Zionist influence at the peace conference that we shall get it.11

Sykes proved dead right. Under the terms of the 1919 Versailles peace conference and the May 1920 San Remo conference of Allied powers, without waiting for League of Nations endorsement and with a clause providing for implementation of the Balfour Declaration the Sykes-Picot agreement, Britain was rewarded with the Mandate of Palestine.

A Jewish state

Ten months later, in March 1921 Colonial Secretary Churchill visited Cairo and Jerusalem with the express intention to “rearrange the Middle East.” Churchill unilaterally divided the British Mandate into a “Jewish national home” and a “Transjordanian Emirate.” His visit was followed soon after by the May 1921 Arab riots in Jaffa, in good part triggered by Arab concerns about the increasing level of Jewish immigration into Palestine. Resultant recommendations for a cap on Jewish immigration by the British High Commissioner in Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, alarmed British Zionist leader Weizmann. Lloyd George and Balfour, in the presence of Churchill, personally reassured Weizmann that by the Declaration “they had always meant a Jewish state.”12 Their promise was realized in May 1948, when Britain relinquished Mandatory Palestine and Israel declared itself an independent state.

The 1917 Balfour Declaration and the Bolshevik Revolution were conflicting actions by counter-posed forces, rationalized by competing worldviews. On the one hand, an internationalist revolution, driven by vast, insurgent working-class and peasant movements, which explicitly allied itself with the aspirations of subject, colonial peoples. On the other, a major imperial power intent on prosecuting its interests in the Middle East and Russia under the guise of Jewish self-determination. A century on, their irreconcilable legacies continue.

Notes

- ↩ John Cornelius, “The Hidden History of the Balfour Declaration,” Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, November 2005, p.6.

- ↩ David Lyon Hurwitz, “Churchill and Palestine,” Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought, 44 (1), Winter 1995, p.18.

- ↩ James Edward Renton, “The historiography of the Balfour declaration: Toward a multi‐causal framework,” Journal of Israeli History, 19 (2), 1998, p. 111.

- ↩ Hurwitz, “Churchill and Palestine,” p. 18.

- ↩ Renton, “The historiography of the Balfour declaration,” p.109.

- ↩ Hurwitz, “Churchill and Palestine,” p. 4.

- ↩ “Zionism Versus Bolshevism. A Struggle For The Soul Of The Jewish People,” Illustrated Sunday Herald (London), February 8, 1920, p. 5

- ↩ Roger D. Markwick, “Violence to Velvet: Revolutions-1917 to 2017,” Slavic Review: Special Issue 1917-2017, The Russian Revolution A Hundred Years Later, 76 (3), Fall, 2017, p. 605.

- ↩ Renton, “The historiography of the Balfour declaration,” p. 114.

- ↩ Renton, “The historiography of the Balfour declaration,” pp. 126-28.

- ↩ Cited in Renton, “The historiography of the Balfour declaration,” p. 125.

- ↩ Hurwitz, “Churchill and Palestine,” p. 19.