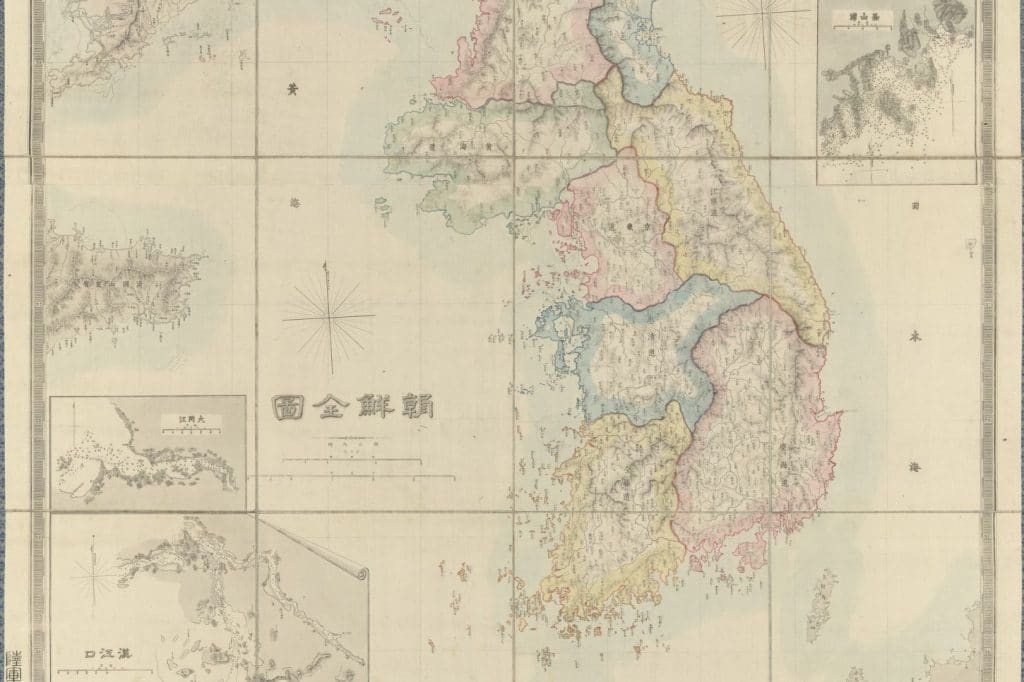

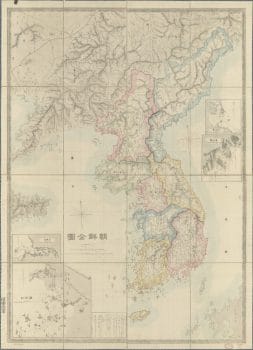

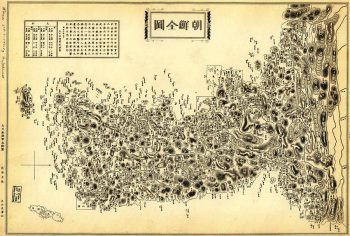

Japan. Rikugun. Sanbōkyoku, and O. M Poe. Chōsen Zenzu. (Tokyo: Rikugun Sanbōkyoku, Meiji 8, 1875) Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. (Accessed March 15, 2018.)

Seventy five million people live in the Korean Peninsula—25 million in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea) and 50 million in the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea). The most highly populated city in the Peninsula is Seoul, the capital of South Korea. If a nuclear bomb were exploded above this city of ten million people, two million would be killed. An all-out assault on the peninsula could result in millions of dead and the entire landmass destroyed for generations. The threat of nuclear war is not idle for the people of Korea. It is a terrible reality.

Thanks to the fear of such a scenario and the winter Olympics in Pyeongchang (South Korea), the two governments of the North and the South have come to an accommodation. In his New Year’s address, North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un said that the DPRK would engage in high-level talks with the ROK. This slowly created a thaw in the atmosphere on the peninsula. The two Koreas marched together at the Olympics and the women’s ice hockey team included players from both Koreas. Meanwhile, political representatives of the North and the South will continue to meet in the De-Militarized Zone (DMZ) to go over the various issues that divide the two governments. For the first time in two years, North and South Korea have used the hotline between the two countries.

This Tricontinental Dossier provides a brief explanation of the crisis in and around the Korean Peninsula. It is not a comprehensive assessment. It is a window into a complex problem. Absent in the general discussion on North Korea are the views of the people of the North—not only the government, but also the ordinary people. It is assumed that they are brainwashed and therefore in need of salvation.

Map of Korean Peninsula (“Chōsen zenzu”) circa 1873. Credit: history-map.com.

This dossier is illustrated with photographs taken by Rafael Stedile, a Brazilian photographer who visited the North in July 2017. These are pictures of ordinary North Koreans going about their business. Rafael shot these pictures in Pyongyang and in Hyangsan Island. We hope that their presence in this dossier provides an antidote to the dehumanised way in which people talk about North Korea, in fact about the Korean Peninsula in general.

The crisis is not merely geopolitical. It is also human. There are people who live in the peninsula–75 million of them. This is about their lives and futures.

Moon’s Proposals

Moon Jae-in, the President of South Korea, has issued several proposals to the DPRK. these include the DPRK’s participation in the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics, inter-Korean dialogues and the end to hostile acts near the military demarcation line separating the two Koreas.

The North Koreans agreed on at least two of these three proposals.

The Moon administration has also stated the possibility of reopening the Kaesong Industrial Region, where South Korean firms operate factories that hire North Korean employees.

Last June, in Berlin, President Moon announced the birth of the ‘Berlin Initiative’ that would include discussions around humanitarian and military a airs in an attempt to reduce the hostility on the peninsula.

Most importantly, President Moon has su ested that he would o er the North Koreans a peace treaty, which would nally end the U.S. War on Korea that began in 1950. In exchange, President Moon hopes to create a Korean peninsula without nuclear weapons, a Nuclear

Free Zone.

Neither the United States nor the North Koreans are eager for this option—but for different reasons. The North Koreans believe that they would be obliterated by the United States if they give up their weapons. They point to Libya, which surrendered its nuclear weapons programme in 2003 and then was destroyed by a NATO war in 2011. ‘That is why we will not give up our weapons’, said a North Korean diplomat.

The United States, on the other hand, would like to see North Korea give up its nuclear programme but would like to retain the option of keeping nuclear weapons at one of its military installations in South Korea.

Currently, the United States has nearly 40,000 personnel at 112 bases in Japan and 23,500 at 83 sites in South Korea. The presence of the US military in South Korea has remained a fixture of Korea’s modern history itself. It is seen by North Korea as a great threat.

Additionally, since 1976, the U.S. and ROK have held annual joint military exercises, known as Key Resolve and Foal Eagle, which involves the participation of 17,000 US and 300,000 South Korean soldiers, with the deployment of nuclear-capable bombers and aircraft carriers as well as mock land invasions. All this is an indicator to North Korea of an imminent invasion.

Fear of Annihilation

Last year, Ri Yong Ho, North Korea’s Foreign Minister called US President Donald Trump’s speech at the United Nations a ‘declaration of war’. This is not the first time that the North Koreans have used that phrase. It was used in 2016 and in 2013 and many times over the past several decades. But, in fact, there is no need for the US to declare war on North Korea. That war has been on going since 1950, with an armistice signed in 1953 (but no peace agreement).

When the North Koreans look across the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), they see a South Korea peppered with US bases and soldiers, as well as US technology designed to annihilate the North. If it looks outwards toward Japan and the Philippines and then to the US homeland, it sees more such equipment—nuclear bombs on missiles that could wipe out the entire population of North Korea.

North Korea’s nuclear programme is a reaction to its encirclement by the United States military force and those of its allies. This nuclear and missile programme is insurance against being attacked. Professor Cheehyung Harrison Kim, who teaches history at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, told Tricontinental that North Korea is not alone in this interpretation. ‘While the superpowers and their allies condemn North Korea, there are plenty of countries—small, southern, Third World, post- colonial countries—who actually support North Korea having nuclear weapons in the name of sovereignty and independence. Many of these countries would pursue a nuclear programme if they could’, said Professor Kim.

When it became clear that North Korea had attained the ability to build nuclear weapons and to deliver them, the United States decided to go further. It began to install an anti-missile system—THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defence)—to counter the North’s advantage. This, of course, put more pressure on an already fearful North.

It was this fear in the North that led South Korea’s President Moon initially to oppose the installation of THAAD. But he reversed his decision under pressure from the United States after the North Koreans tested an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) on July 28, 2017. The US began to install the system in September 2017. In December, the US Congress approved a $12.3 billion tranche for the Missile Defence Agency Budget—a 50% increase from the previous year. All of these moves egged on North Korea to further escalation.

So, does North Korea have a legitimate reason to be concerned about the US-ROK military alliance and by the build-up of US weapons systems around the peninsula?

To answer this question, Tricontinental reached out to Charles Armstrong, Professor of Korean Studies at Columbia University.

‘The DPRK has good reason to believe the US and the ROK want to destroy it. The annual US-ROK military exercises are among the largest in the world, and appear extremely threatening to the DPRK’, Armstrong told Tricontinental.

Furthermore, US President Donald Trump’s comments during last year’s United Nations general assembly, in which he publicly threatened to ‘totally destroy’ the DPRK along with the additional sanctions his administration imposed against North Korea, could be seen as a step forward along the traditional path to US military action for regime change.

‘So despite moments of reduced tension and cooperation on the Korean peninsula and between the US and DPRK in recent decades, the US threat appears severe and even existential. Under these circumstances, robust defence against the US is prudent, not paranoid’, Armstrong added.

North Korea has made significant advances over the past two decades in developing a nuclear weapons arsenal, including a wide variety of ballistic and powerful nuclear tests. In 2017, North Korea conducted 16 missile tests and the underground detonation of a nuclear device. By Professor Armstrong’s standard, North Korea’s approach over past decade has been prudent, not paranoid.

Memories of Devastation

The inter-Korean tensions extends beyond the North Korean nuclear problem. They and can be traced back to 1945 with the ideological, political and military division of Korea, which prompted the start of the Cold War.

At the end of the Second World War, the Korean peninsula was divided into two zones, the North (backed by the USSR) and the South (backed by the United States).

Tensions would eventually flare up, leading to the outbreak of the Korean War (1950-1953), which to this day has left historical wounds in North Korean society.

After 30 years of Japanese rule over Korea, the greatest threat to sovereignty and independence of the North Korean people was the United States.

Following the Korean War Ceasefire Agreement of 1953, the peninsula was devastated, particularly the North.

‘The memory of U.S. atrocities in the war is one way the DPRK unites and mobilizes its population. But the war was unquestionably devastating for the North. This is mainly due to the American bombing, which essentially carried over the “saturating bombing” approach that destroyed German and Japanese cities in World War II. Every city in the DPRK was virtually reduced to rubble; millions were killed, maimed, and made refugees; some 70% of war dead were civilians’, Professor Armstrong told Tricontinental.

It is now clear that the US bombing of North Korea destroyed 90% of the structures north of the 38th parallel, which is the border between the North and the South.

Korea’s Independence

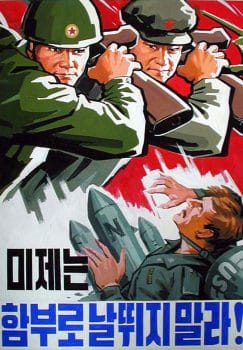

Poster for “International Campaign of Solidarity with the People of Korea.” Credit: Gladys Acosta (OSPAAAL, 1968).

Much of the Western debate on North Korea assumes that South Korea will comply with the mandates imposed by Washington. While South Korea is a US ally, it would also suffer the most if conflict were to unfold, which could lead to a much needed warming of ties between the two Koreas.

In the event of military conflict on the peninsula, a 2017 report published by the US Congressional Research Service, estimated that ‘Hundreds of thousands of South Koreans would die in the first few hours of combat—from artillery, from rockets, from short range missiles—and if this war would escalate to the nuclear level, then you are looking at tens of millions of casualties and the destruction of the eleventh largest economy in the world’. This should be a sufficient deterrent to war.

It is why a majority of South Koreans (58%) told Gallup last year—at the height of the tension—that there was ‘no possibility’ that North Korea would cause a war.

In August, South Korean President Moon issued a strong statement saying that the country will not sit quietly as tensions escalate between the US and North Korea. During his remarks, Moon asserted the right to veto any military action against North Korea, adding that the decision should be made by ‘ourselves and not by anyone else’. Moon’s concerns about national sovereignty are a consistent theme in South Korean politics partially due to opposition to the idea of a US-led military strike against North Korea.

‘The South Korean government, along with South Korean civil society and media’, Professor Kim told

Tricontinental, is the most important actor in dealing with North Korea, no matter how loud the voices are coming from the US, China, Japan and Russia. This is the same for North Korea. While it must play the role of “little sibling” to China and Russia, it can always bypass them and talk to South Korea. This is happening now and, in my opinion, is the best way for progress. The two countries must start talking first before anything else’.

Nonetheless, Professor Kim says, there is always the possibility that the South Korean government would buckle to pressure from the United States. Liberal populist leaders—such as Kim Daejung, Roh Moohyun, and today’s Moon—are elected on a pro-people platform that includes redistribution policies to the South Korean population and peace overtures to the North Koreans. Once elected, however, these politicians often appease the United States on behalf of compliant South Korean corporations. The situation, Professor Kim says, is complex because these administrations ‘are able to deal with North Korea more independently, even while keeping their status quo with the US. This is why Moon Jae-in recently said that he is thankful that Trump made it possible for North Korea and South Korea to talk directly.’

A little flattery might sweeten the possibility for peace, although it will not be enough to hold back the immense appetite of the US government to squeeze North Korea as part of its agenda to encircle and diminish China’s role in Asia and the world.

China, which shares strong cultural and historical ties with North Korea (and the Korean Peninsula as a whole), places a justifiably high premium on North Korea’s political stability. The bilateral relationship between the two countries is very important both in terms of the larger regional dynamics and nuclear issue. But China’s delicate role in the Korean Peninsula has become part of the hostile Cold War-like dynamics between the United States and the country that it increasingly sees as its main adversary, China. If war against North Korea would weaken China, then there are people in the US government who would risk a war—however catastrophic.

Possibility of War

The possibility of war on the Korean Peninsula cannot be ruled out, according to Alexander Vorontsov of the Russian Academy of Sciences, who recently travelled to North Korea, where he held high-level discussions with Foreign Ministry officials about the possibility of war with the United States.

During his frank conversations, the North Korean representatives expressed genuine concern over the United States’ geo-political ambitions, warning that US officials would be willing to accept the tremendous loss in human life in the event of a military conflict with North Korea.

The North Korean concerns are further validated by a recent report published by the US Army War College’s Strategic Studies Institute, which identified a US-led military invasion as one of the key agenda items for 2018.

‘The [US military] seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of the US military strategy and the use of US land forces toward North Korea and Northeast Asia,’ the Key Strategic Issues List (KSIL) stated.

Under current military law, all army officials are required to follow ‘lawful orders’ of the US commander-in-chief. However, there are important discussions underway regarding the legality of a preventative nuclear attack—or even whether a retaliatory nuclear attack, resulting in the death of millions of innocent bystanders—is legally permissible.

An open letter (pdf) to lawmakers, signed by nearly three- dozen United States-based grassroots organisations, demanded that members of the US Congress impose tighter restrictions on President Trump’s ability to unilaterally authorise the use of nuclear weapons.

In their letter, the groups cited two bills that legislators should support in order to restrict Trump’s authority to launch a nuclear war—the ‘No First Use’ bill introduced by Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.) and the bicameral ‘Restricting First Use of Nuclear Weapons Act’ introduced by Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.).

‘There’s no better example of the unique danger Trump poses than the unfolding crisis with North Korea, where his cavalier attitude towards nuclear war puts the whole world at risk. Trump should be doing everything in his power to reduce the threat of nuclear conflict by jump-starting diplomatic talks with North Korea’, the organizations write in their letter. There is an illusion here. The United States simply does not want to ‘jump-start’ any such discussion. To ask the US government to do so perpetuates the belief that the US would ever do this as an act of faith.

On January 26, Choe Song-ho of the North Korea’s Social Science Institute published a warning to the country in Redong Sinmun. Choe wrote that until the United States draws down its military presence from the peninsula ‘a dark vortex of nuclear war lurks like a time bomb’.

Choe’s comments came after a draft of the Trump Administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was leaked to the media, which include proposals to expand the United States government nuclear programme. According to the leaked document, the White House hopes to build new submarine-launched cruise missiles, increase the supply of low-yield nuclear weapons and consider nuclear retaliation against nonnuclear attacks.

Close observers of the crisis in the Korean Peninsula agree that the militarization of North-East Asia exacerbates this tension. Threats from US bases that run along the rim of Asia constitute as well as military exercises with partners states constitutes major impediments to peace.

It is the South Koreans and the North Koreans who have been the main drivers for a peace deal. Every opportunity must be found to make it possible for these two halves of the Korean Peninsula to pave their road to peace.

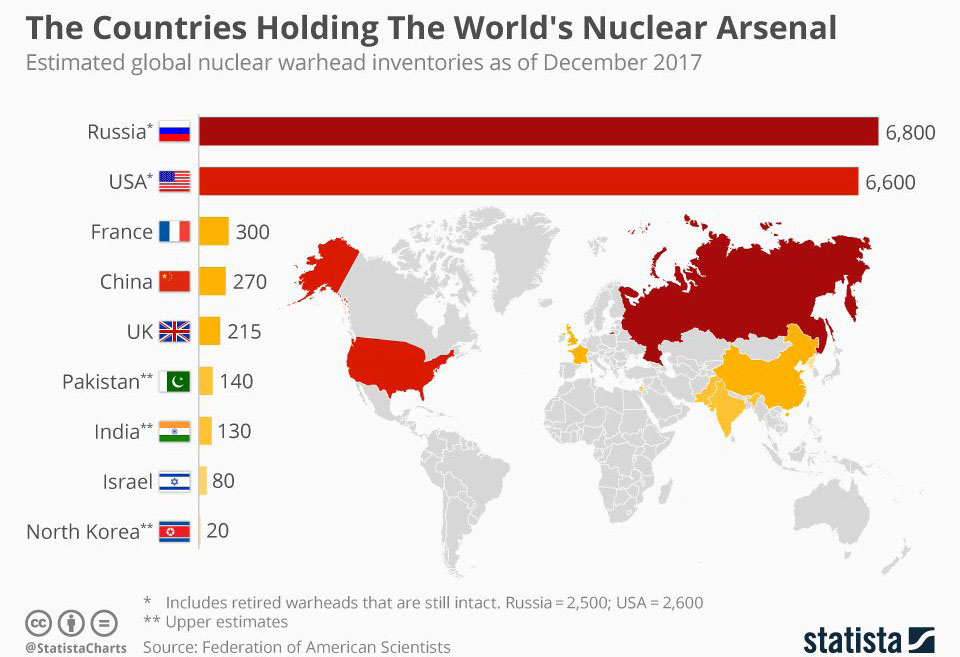

Martin Armstrong, “The Countries Holding The World’s Nuclear Arsenal,” Statista (Mar 2, 2018).

Possibility of Peace

The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) won the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize. The reason that they were awarded the prize was for their active work to push through the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons—a treaty negotiated and concluded by 122 member states of the United Nations. At the Nobel ceremony, ICAN’s chief Beatrice Fihn named the main countries that have not joined the treaty—the United States, Russia, Britain, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea. She said,

I call on every nation to join the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. The United States: choose freedom over fear. Russia: choose disarmament over destruction. Britain: choose the rule of law over oppression. France: choose human rights over terror. China: choose reason over irrationality. India: choose sense over senselessness. Pakistan: choose logic over Armageddon. Israel: choose common sense over obliteration. North Korea: choose wisdom over ruin.

Thus far, the bulk of the nuclear weapons in the world are held by the United States and Russia.

North Korea has a minimal arsenal, although lethal. It will not surrender its arsenal as long as its adversaries hold on to their weapons. North Korea struggles with crippling sanctions. Neither the threat of war nor the sanctions will bring peace to the peninsula. Peace is attained through trust and negotiations. It is the United States and its allies that have created an atmosphere of distrust around the Korean Peninsula. The two Koreas—meanwhile—have been trying their best to find a way to resolve their differences. They must be allowed to breathe. Their peace path should not be suffocated.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research is an international, movement-driven institution focused on stimulating intellectual debate that serves people’s aspirations. Download the PDF version of this report.