The Chinese economy is big. In 2017, it was the world’s biggest based on purchasing power parity. Its output equaled $23.12 trillion, compared with $19.9 trillion for the EU and $19.3 trillion for the U.S.

China also regained its position as the world’s largest exporter in 2017, topping the EU which held the position in 2016. Chinese exports totaled $2.2 trillion compared with EU exports of $1.9 trillion. The United States was third, exporting $1.6 trillion.

The Chinese economy also recorded an impressive 6.9 percent increase in growth last year, easily beating the government’s 2017 target of 6.5 percent and the 6.7 percent rate of growth in 2016. According to international estimates, China was responsible for approximately 30 percent of global economic growth in 2017.

The Chinese government as well as many international analysts also claim that China has entered a new economic phase, one that is far more domestic-centered and responsive to popular needs, and thus more stable than in the past when the country relied on exports to record even higher rates of growth.

It all sounds good. However, there are many reasons to question China’s growth record as well as the stability of the country’s economy and turn towards a new domestic-centered growth strategy. Glowing reports aside, hard times might well lie ahead for workers in China and the broader Asian region.

Chinese Growth

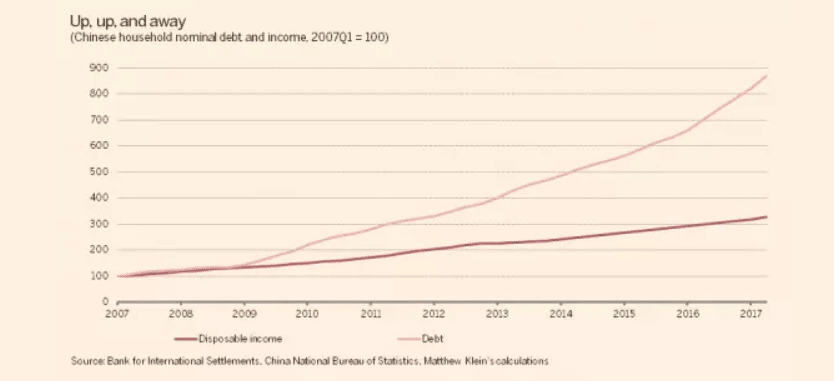

As the chart below shows, China’s rate of growth fell for six straight years, from 2011 to 2016, before registering an increase in 2017. Current predictions are for a further decline, down to 6.5 percent, in 2018.

However, Chinese growth figures still need to be taken with the proverbial “grain of salt.” As Lucy Hornby, Archie Zhang, and Jane Pong discuss in a Financial Times article, Chinese provinces routinely fudge their growth data, which compromises the reliability of national growth figures. For example:

Inner Mongolia, one of China’s most coal-dependent areas, and the major northern port city of Tianjin, have admitted to falsifying data that will probably require their 2016 GDP to be revised down. They join neighboring Liaoning, the first province to admit to a contraction during the four-year correction in commodities markets.

Inner Mongolia admitted this month that its data for “added value of industrial enterprises of a certain scale” were inflated 40 per cent in 2016. According to the Chinese statistical yearbook, secondary industry comprises 47 per cent of its GDP. Assuming its 2015 figures are accurate, the revised 2016 figures mean the region’s economy shrank 13 per cent. . . .

Like Inner Mongolia, Liaoning admitted to a contraction in 2016 compared with its official performance in 2015. Liaoning admits it faked data for about five years but has not issued a revised series…

Tianjin, one of the big ports that services northern China, could also see a revision. Its Binhai financial district, which offers tax and foreign exchange incentives to registered businesses, swelled to comprise roughly half of Tianjin’s reported GDP last year.

Binhai included in GDP the commercial activity of companies that were only registered there for tax purposes, according to revelations last week. That could result in a 20 per cent drop in reported GDP for Tianjin in 2017, according to FT calculations. Binhai’s high debt levels and access to domestic and international financing make its phantom results a concern for broader markets.

Another possible data offender is Shanxi, China’s most coal-dependent province. Its official GDP growth held up admirably during the commodities downturn.

Last summer China’s anti-corruption watchdog announced unspecified problems with Jilin’s data, adding another troubled northeastern province to the list of candidates to watch.

Wang Xiangwei, former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post, sums up the situation as follows:

This [falsification of data] has given rise to a popular saying that “data makes an official and an official makes data”. The malpractice is so rampant and blatant that over the years, a long-running joke is that simply adding up the figures from all the provinces and municipalities reveals a sum that overshoots the national GDP–by 6.1 trillion yuan (more than 10 per cent!) in 2013, 4.78 trillion yuan in 2014, and 3.6 trillion yuan in 2016.

This data manipulation certainly suggests that China has regularly failed to meet government growth targets. Perhaps more importantly, even the overstated published nation growth statistics show that China’s rate of growth has steadily fallen.

Debt problems threaten economic stability

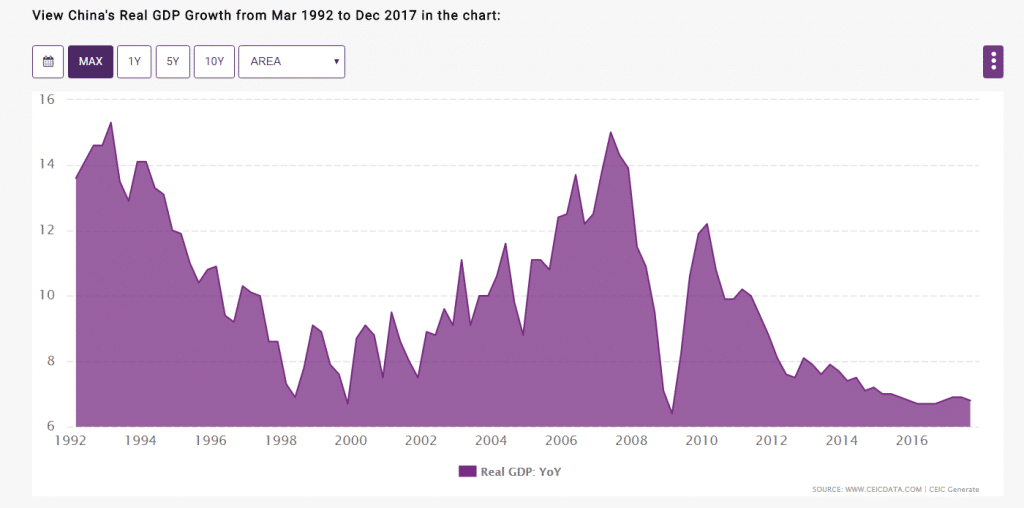

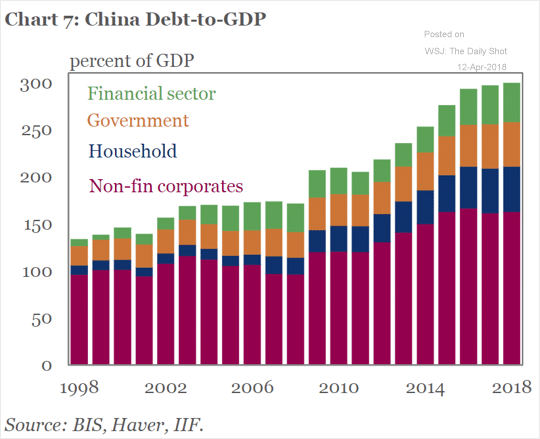

There are also reasons to doubt that China can sustain its targeted growth rate of 6.5 percent. A major reason, as the next chart shows, is that China’s growth has been underpinned by ever increasing debt. Said differently, it appears that ever more debt is required to sustain ever lower rates of growth.

As Matthew C Klein, writing in the Financial Times Alphaville Blog, explains:

The rapidity and size of China’s debt boom in the past decade has been almost entirely without precedent. The few precedents that do exist—Japan in the 1980s, the U.S. in the 1920s—are not encouraging.

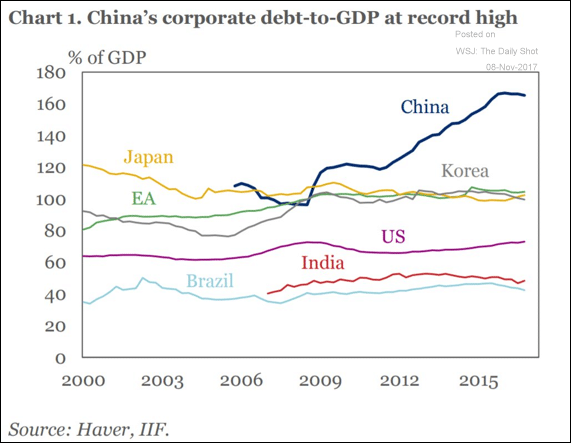

Most coverage has rightly focused on China’s corporate sector, particularly the debts that state-owned enterprises owe to the big four state-owned banks. After all, these liabilities constitute the biggest bulk of the total debt outstanding, and also explain most of the total growth in Chinese debt since the mid-2000s.

The explosive nature of China’s corporate sector debt growth is well illustrated by comparisons to the relatively stable corporate debt ratios in other major countries, as shown in the following chart.

China’s growing debt means it likely that sometime in the not too distant future the Chinese state will be forced to tighten its monetary policy, making it harder for Chinese companies to borrow to finance their existing levels of employment and investment, thus triggering a potentially sharp slowdown in growth. At the same time, since much of China’s corporate debt is owed to government-controlled banks, it is also likely that the Chinese state will be able to limit the economic fallout from expected corporate defaults and avoid a major financial crisis.

But, while corporate debt has drawn the most attention, household debt is also on the rise, and not so easily managed if serious repayment problems develop. According to Klein,

Since the start of 2007, Chinese disposable household income has grown about 12 per cent each year on average, while Chinese household debt has grown about 23 per cent each year on average. The cumulative effect [as illustrated below] is that (nominal) income has slightly more than tripled but debts have grown by nearly a factor of nine. . . .

All this is finally starting to affect the aggregate debt numbers. Household debt in China is still small relative to the total—about 18 per cent as of mid-2017—but household borrowers are now responsible for about one third of the growth in total nonfinancial debt.

By mid-2017, Chinese households held debt equal to approximately 106 percent of their disposable income, roughly equal to the current American ratio. What makes Chinese household debt so dangerous is that, as Klein notes, “households cannot service their debts out of GDP. Instead they have to rely on their meagre incomes.” And as we see below, the share of Chinese national output going to households is not only low but has generally been trending downward. By comparison, disposable income in the U.S. normally runs around 72-76 percent of GDP.

In addition, it has been “finance companies and private loan sharks” that have done most of the consumer lending, not state banks. This will make it harder for the state to keep repayment problems from having a significant negative effect on domestic economic activity.

In addition, it has been “finance companies and private loan sharks” that have done most of the consumer lending, not state banks. This will make it harder for the state to keep repayment problems from having a significant negative effect on domestic economic activity.

Thus, while Chinese officials argue that China’s new lower rate of growth represents a switch to a new more stable level of economic activity, the country’s debt explosion suggests otherwise. As Michael Pettis argues in his August 14, 2017 Monthly Report on China:

To argue that the authorities have been successful in stabilizing GDP growth rates and now must address credit growth misses the point entirely. If GDP growth “stabilizes” while credit growth accelerates, GDP growth cannot be said to have stabilized, at least not in any meaningful way. Chinese economic growth can only be said to have stabilized if GDP growth rates remain constant without any increase in the debt burden–i.e. credit grows in line with or slower than nominal GDP–and in my opinion, as I said above, this cannot happen except at growth rates well below half the current reported GDP growth rate, or less than 3 percent.

What new growth model?

For several years Chinese leaders have acknowledged the need for a new growth model that would produce slower but more sustainable rates of growth. As Chinese Premier Li Keqiang explained in a recent speech to the National People’s Congress:

China’s economy is now in a pivotal period in the transformation of its growth model, its structural improvement and its shift to new growth drivers. China’s economy is transitioning from a phase of rapid growth to a stage of high-quality development.

In other words, China is said to have abandoned its past export-driven high-speed growth strategy in favor of a slower, more domestic, human-centered growth strategy. China’s current slower growth is in line with this transformation and thus should not be taken as a sign of economic weakness.

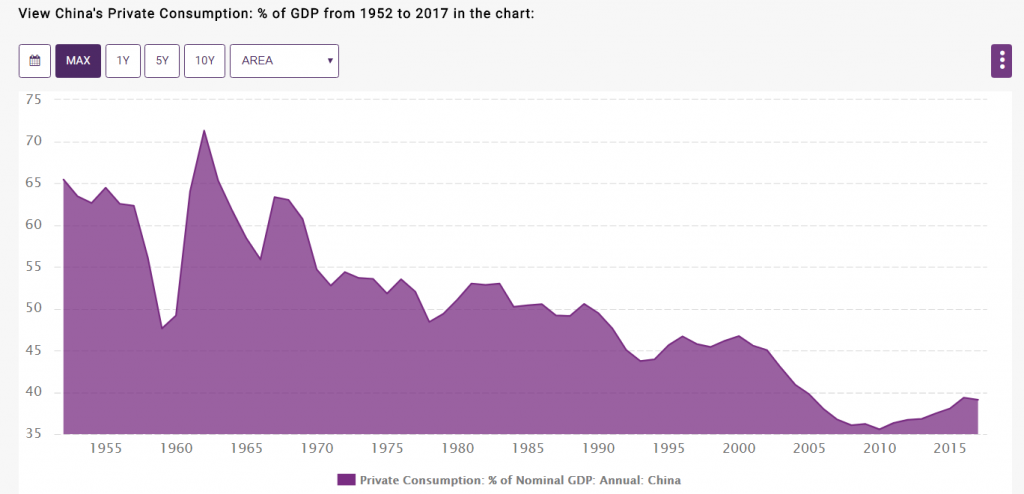

However, there are few signs of this transformation, other than a lower rate of growth. For example, one hallmark of the new growth model is supposed to be the shift from external to domestic, private consumption-based drivers of growth. The slowdown in the global economy in the post 2008 period certainly makes such a shift necessary. But the data, as shown below, reveals that there has been no significant gain in private consumption’s share of GDP. In fact, it actually declined in 2017.

However, there are few signs of this transformation, other than a lower rate of growth. For example, one hallmark of the new growth model is supposed to be the shift from external to domestic, private consumption-based drivers of growth. The slowdown in the global economy in the post 2008 period certainly makes such a shift necessary. But the data, as shown below, reveals that there has been no significant gain in private consumption’s share of GDP. In fact, it actually declined in 2017.

China’s private consumption accounted for 39.1 percent of GDP in Dec 2017, compared with a ratio of 39.4 percent the previous year. The ratio recorded an all-time high of 71.3 percent in Dec 1962 and a record low of 35.6 percent in Dec 2010. And as we saw above, there has been no significant increase in disposable income’s share of GDP. Moreover, the existing consumption, in line with income trends, remains heavily skewed towards the wealthy.

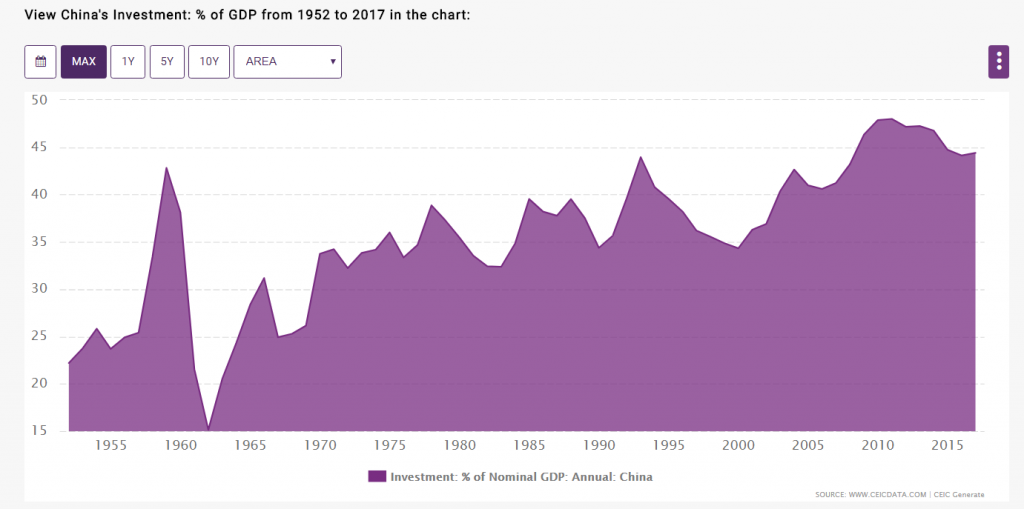

What has remained high, as we see in the next chart, is investment, a pillar of the old growth model.

China’s Investment accounted for 44.4 percent of GDP in Dec 2017, compared with a ratio of 44.1 percent in the previous year. The ratio reached an all-time high of 48.0 percent in Dec 2011 and a record low of 15.1 percent in Dec 1962.

China’s Investment accounted for 44.4 percent of GDP in Dec 2017, compared with a ratio of 44.1 percent in the previous year. The ratio reached an all-time high of 48.0 percent in Dec 2011 and a record low of 15.1 percent in Dec 1962.

This investment continues to emphasize infrastructure, real estate development and enhancing manufacturing capacity. One example:

A symbol of the investment addiction can be found in “China’s Manhattan.”

Tianjin’s Conch Bay, a 110-hectare district with a cluster of 40 high-rise buildings, was supposed to be the country’s new financial capital as outlays surged over the past several years. But in late November there were few signs of life. A number of buildings were still under construction; the streets were empty; and even completed buildings had no occupants.

From 2000 to 2010, investment in Tianjin—the hometown of former Premier Wen Jiabao—swelled by a factor of 10.3.

In fact, despite official pronouncements, China’s accelerated growth in 2017 owes much to external sources of demand. As Reuters describes:

China’s economy grew faster than expected in the fourth quarter of 2017, as an export recovery helped the country post its first annual acceleration in growth in seven years, defying concerns that intensifying curbs on industry and credit would hurt expansion. . . .

A synchronized uptick in the global economy over the past year, driven in part by a surge in demand for semiconductors and other technology products, has been a boon to China and much of trade-dependent Asia, with Chinese exports in 2017 growing at their quickest pace in four years.

With fixed asset-investment growth at the weakest pace since 1999, exports helped pick up the slack.

“Real growth of overall exports…more than fully (explained) the pick-up in GDP growth last year,” Oxford Economics head of Asia economics Louis Kuijs wrote in a note.

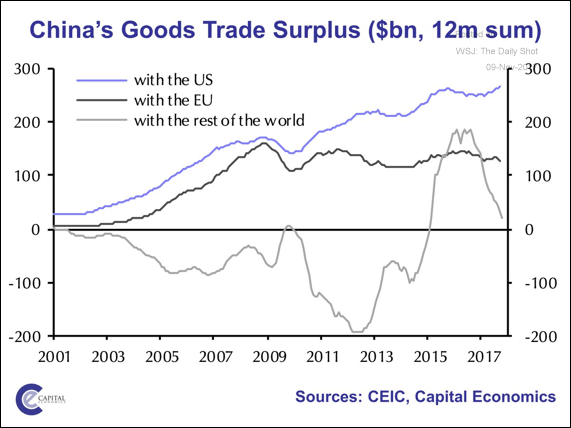

And as we can see from the chart below, China’s export gains continue to depend heavily on the U.S. market—a market that is becoming increasingly problematic in the wake of U.S. tariff threats.

China’s real new growth strategy: The One Belt, One Road initiative

There are many pressures keeping Chinese leaders from seriously pursuing a real domestic-centered, consumption-based growth model. One of the most important is that the interests of powerful political forces would be damaged if the government took meaningful steps to significantly increase the wages and improve the working conditions of Chinese workers. And since many in the government and party directly benefit from existing relations of production they have little reason to pursue a strategy that would threaten the profitability of China-based production activity.

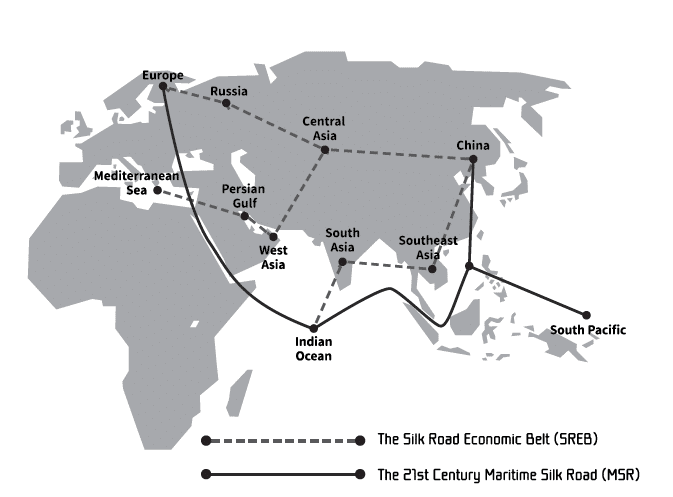

At the same time, it was clear to Chinese leaders that a new strategy was necessary to keep Chinese growth from further decline, an outcome which they feared could spur regime-threatening labor militancy. Their answer, first discussed in 2013, appears to be the One Belt, One Road initiative. The beauty of this initiative is that it allows the existing political economy to continue functioning with little change while opening up new outlets for basic industrial products produced by leading state firms, creating new export markets for private producers, and expanding the huge infrastructure that underpins the Chinese construction industry.

Asia Monitor Research Center, in the introduction to its Asian Labor Update issue on the One Belt, One Road initiative, describes what is at stake as follows:

Xi Jinping’s One Belt, One Road has been described as the next round of “opening up” by the Chinese government, following the development of Special Economic Zones and China’s accession to the WTO. Indeed, the OBOR strategy can be seen as a very significant and ambitious next step in the expansion of the role that China plays globally and its implementation will impact on the lives of millions of people domestically and globally.

Chinese government strategies towards both the BRICS and even more so towards OBOR, which has been dubbed “globalization 2.0”, potentially have important implications for the direction of globalization in the future. Given the way that China’s development strategies have led to significant environmental destruction and labor rights violations domestically, and the way that its investment overseas has been frequently criticized or led to opposition due to their adverse social and environmental consequences, suggest that there are legitimate causes for concern about the impacts on people and the environment of this direction.

In fact, the special issue includes several contributions which highlight the negative consequences of this initiative. The initiative is first and foremost designed to enable Chinese companies to build roads, railway lines, ports and power grids for the benefit of China’s economy. These projects come with massive environmental degradation, displacement of local communities, and local labor exploitation. It also aims to advance Chinese efforts to control agricultural land and raw materials in targeted countries and promote the creation of Yuan currency area.

It remains to be seen how successful the One Belt, One Road initiative will be in achieving its aims. What does seem clear is the talk of a new more stable, humane, high-quality Chinese economy is largely just that, talk. Chinese leaders appear heavily invested in trying to breathe new life into the country’s existing growth model, a model that comes with enormous human and environmental costs.