There is no doubt that President Trump is upending global trade. He has unleashed a trade war with China as well as with some of the U.S.’ s purported allies, using grounds of “threats to national security” to impose tariffs on many U.S. imports. The likely retaliation will obviously affect some U.S. exports in turn.

The trajectory of world trade suddenly looks quite uncertain—and this will also depress investment across the trading world.

So the Trump effect on world trade is clearly just beginning. But the naked self-interest of Trump’s moves, the “America first” orientation declared by the U.S. President, should not be interpreted only in the doomsaying tones of much of the mainstream media.

The truth is that this orientation is not new: U.S. trade policy always put the U.S. first—or at the very least, privileged the interests of U.S. capital vis-à-vis all other players.

U.S. policy

The U.S. strongly influenced the Uruguay Round of the GATT that introduced many new elements into trade negotiations (such as services, intellectual property provisions and trade-related investment measures) to benefit U.S. multinationals.

Subsequently, despite the promises made in the so-called “Doha Round”, the U.S. and other advanced countries simply ignored the genuine demands and concerns about the unfair functioning of the WTO agreements.

In other bilateral and plurilateral negotiations, they have aggressively pushed for even stronger rules for intellectual property that enabled monopolies and rent-seeking by their own companies, and then sought to protect them through Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanisms, with little concern for the impact on other economies.

They have denied developing countries the right to ensure their own food security even as they have used the small print of various agreements to continue to give as many subsidies as they like themselves.

The difference is that today President Trump, as the head of the waning superpower, is no longer as interested in supporting the neo-liberal order that allowed the U.S. to retain global supremacy for so long, and is happy to declare it as being against U.S. interests.

Of course, he will still promote U.S. capital as aggressively as was done before, but the apparently “neutral” rules of the game that were pushed by previous U.S. Presidents are now seen as providing too many opportunities to pretenders, and therefore are sought to be overturned.

This is obviously a challenge for all U.S. trading partners, but this also presents many developing countries with significant opportunities.

Periods of global capitalist instability are generally seen as dark times, but through history they have also been periods when the established international division of labour (which tends to get cemented in more stable times) was changed, because they allowed newly industrialising countries to access markets and have some freedom in their own industrial policies.

But even before the breakout of a trade war, which seems more and more possible, how much has the Trump administration already affected U.S. trade patterns? In the absence of clear policies over the past year, even the bellicose statements and threats made by the U.S. President could be expected to have some impact.

Trading patterns

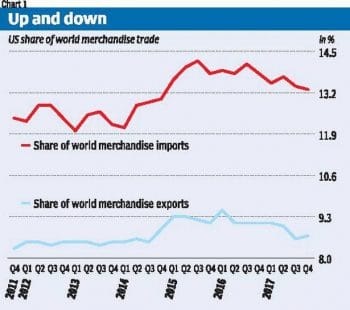

So let us examine the trade patterns of the U.S. over the period of the second Obama administration and the first year of the Trump regime, to see if there was any significant change. Chart 1 describes the quarterly shares of the U.S. in world merchandise trade, the area in which Trump claims that the U.S. has been “exploited” by trading partners because of its large deficits. There is of course an obvious logical fallacy here, of treating net exports as inherently more advantageous even for the holder of the world’s reserve currency.

Chart 1 describes the quarterly shares of the U.S. in world merchandise trade, the area in which Trump claims that the U.S. has been “exploited” by trading partners because of its large deficits. There is of course an obvious logical fallacy here, of treating net exports as inherently more advantageous even for the holder of the world’s reserve currency.

But in fact, as evident from Chart 1, U.S. shares of both global exports and imports (which increased from 2011 to the end of 2014, began declining in the first quarter of 2015 in the middle of Obama’s second tenure.

This has continued into Trump’s first year—but over this later period the U.S. trade deficit widened after reducing for several years. It is well known that merchandise trade represents only a part of total trade, and services trade has increased sharply in the period of globalisation. Chart 2 shows that the U.S. has had surpluses in services trade, so that the net trade balance in both goods and services is somewhat lower.

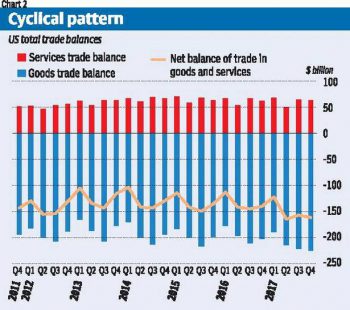

It is well known that merchandise trade represents only a part of total trade, and services trade has increased sharply in the period of globalisation. Chart 2 shows that the U.S. has had surpluses in services trade, so that the net trade balance in both goods and services is somewhat lower.

Here too, the broadly cyclical pattern of the previous four years continued into Trump’s first year. Even so, the increase in the merchandise trade deficit was so large that the services surplus could not compensate, and the net deficit has been increasing sharply after Trump came to power. It is true that the U.S. economy grew faster last year, which would have affected imports as well. But the interesting point to note is that the services trade surplus did not increase as much as could be expected.

It is true that the U.S. economy grew faster last year, which would have affected imports as well. But the interesting point to note is that the services trade surplus did not increase as much as could be expected.

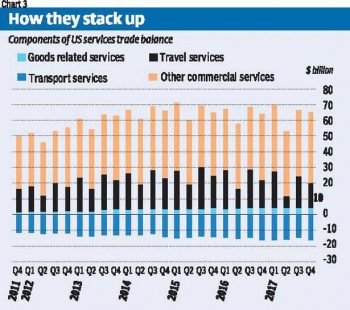

The breakdown of the U.S. services balance, shown in Chart 3, is revealing. The U.S. has a deficit in transport services, which tend to be related to its volume of trade. Travel services have been volatile, but the net export of such services (essentially through tourism) declined in the past year.

The big story is in other commercial services, which include the range of services in which U.S. companies are globally competitive: construction; insurance and pension services; charges for the use of intellectual property; telecommunications, computer and information services; other business services; and personal, cultural and recreational services.

The trade balance in this category increased significantly from $164 billion in the last year of the Obama administration, to $175 billion in the first year of President Trump.

For whatever reason, the rents of U.S. MNCs from various kinds of intellectual property and market dominance in media and entertainment industries, as well as the sector so beloved of the U.S. President, construction, have already shown even greater increases during his tenure so far.

The implications

What are the implications of all this for the US’s trading partners? The obvious lessons are already well known: do not expect any concessions from the U.S. on any front and watch your own back. But there are other less obvious lessons.

Pious neo-liberal multilateralism, as expressed in the rules and operations of the WTO, created a system of monstrous but legally entrenched inequalities.

The implosion of that system lays bare some of its hypocrisy. Perhaps smashing the myth of benign intent will allow all countries to demand policy space to address the real concerns of their own citizens.