A recent article published in the American Economic Review, “Global Inequality Dynamics: New Findings from WID.world,” draws upon the World Wealth and Income Database to examine trends in global inequality.

Two main takeaways:

- U.S. economic dynamics have greatly enriched those at the top at the expense of the great majority.

- Chinese elites, thanks to China’s post-Mao capitalist transformation, are hard at work replicating U.S. patterns of inequality.

While U.S. and Chinese political leaders threaten each other with talk of trade wars, there has certainly been a lot of win-win for those at the top in both countries.

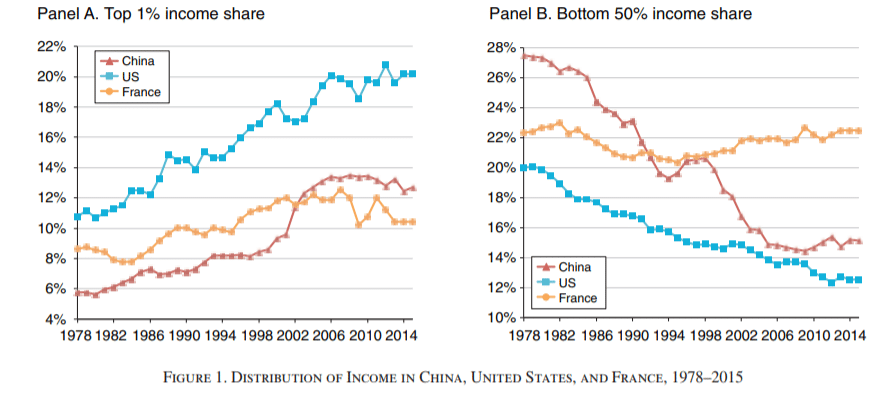

Income inequality

Figure 1, below, highlights the sharp rise in the income share of the top 1 percent and the sharp fall in the income share of the bottom 50 percent in the United States. It also shows that while China’s elite have also found globalization dynamics beneficial, especially after the country’s 2001 entrance into the WTO, their relative income position has changed little since the Great Recession. Perhaps most striking is the steady fall in the income share going to the bottom 50 percent of Chinese since the late 1970s start of the country’s process of marketization and privatization. In contrast to both countries, income shares in France have been remarkably stable.

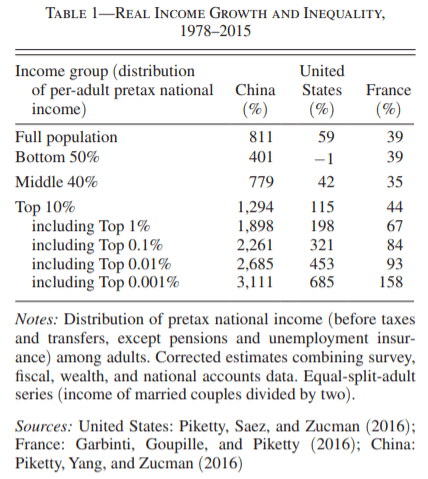

As shown in Table 1, real income growth for those at the top is positively correlated with earnings—the greater the income, the greater the percentage gain. Things were not so positive for the bottom 50 percent in the U.S., as the group actually lost income over the period despite overall economic growth.

In the case of China, it appears that growth was so great over the period 1978 to 2015, that even the bottom 50 percent benefited, with that group’s income growing by 401 percent. However, that figure needs to be treated with caution. Before the reform period, most Chinese workers earned low salaries but that was balanced by the fact that the Chinese government provided them with a vast array of goods and services at little or no cost. Everything changed with the country’s capitalist transformation. Thus, while Chinese workers now earn far more money from their work than in the past, their costs for housing, health care, food, transportation, education, and the like, has also soared. As a result, income gains for most Chinese likely overstate the benefits they have received from their country’s high rates of growth.

Privatization and concentration of wealth

The article also highlighted trends in the share of private wealth. As the authors comment:

We observe a general rise of the ratio between net private wealth and national income in nearly all countries in recent decades. It is striking to see that this phenomenon was largely unaffected by the 2008 financial crisis. The unusually large rise of the ratio for China is notable: net private wealth was a little above 100 percent of national income in 1978, while it is above 450 percent in 2015. The private wealth-income ratio in China is now approaching the levels observed in the United States (500 percent), United Kingdom, and France (550–600 percent).

Figure 2 illustrates trends in the share of public wealth in national wealth. China’s downward trend reflects the country’s capitalist transformation, which has led to an increase in the share of national wealth in private hands. More striking is the fact that “Net public wealth has become negative in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom, and is only slightly positive in Germany and France.”

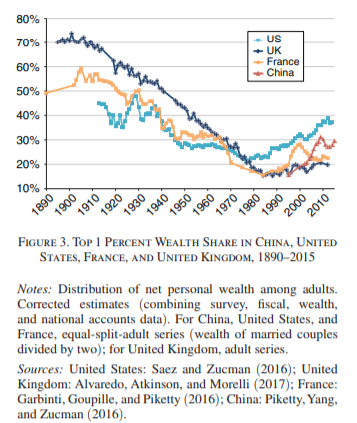

Figure 3 reveals a sharp and sustained rise in the share of wealth held by the top 1 percent in the United States and China in recent decades, and more moderate increases in France and the United Kingdom.

It remains to be seen whether these trends in income and wealth inequality will continue. The fact that inequality trends in France differ greatly from those in the U.S. and China strongly suggests that while capitalist globalization exerts a strong pull in favor of the rich and powerful everywhere, national institutions and relations of power also matter. And that means that future developments will likely depend heavily on the actions of workers in the U.S. and China, the two countries whose accumulation dynamics appear to exert the strongest force on the international economy.