The following talk, given on 20 May 2018, was one of a hundred panels at the Montreal conference “The Great Transition: Preparing a World Beyond Capitalism.” The conference attracted more than 1,500 participants. The talk was given in French; what follows is a translation. It formed part of a panel, “The Dawn of Our Liberation,” which also included talks by Aziz Fall, Ameth Lô, and Daria Dyakonova.

The League Against Imperialism was launched in Brussels in 1927 with the goal of forging unity between colonized peoples and workers in the colonizing countries. Initiated by a wing of the Communist International, it was the first attempt to structure international anti-colonial unity. This brief presentation will focus on its origins and the causes of its decline.

An initial wave of anti-imperialist uprisings took place in the first years of the twentieth century (China, Iran, Mexico), but these events did not evoke significant expressions of solidarity in Europe. The situation was changed, however, by the impact of World War 1 and the Russian revolution of 1917. In particular, the new Russian Soviet government stood for liberation of peoples subjected to direct or indirect colonial oppression, which then afflicted almost all of Asia and Africa. Indeed, the Russian uprising was itself in part a revolt of Asiatic peoples oppressed by tsarism.

The Soviet government’s proclamation in 1917 of the right of peoples to self-determination had immense global impact. Self-determination was also a guiding principle of the Communist International (Comintern) from its founding in 1919. The following year the Comintern convened the first transnational gathering of colonized peoples: the First Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku, Azerbaijan. The Baku Congress in 1920, attended by almost two thousand delegates from Central Asia and the Middle East, adopted resolutions to orient the anti-colonial struggle. In 1922, a similar conference was held for delegates from the Far East.

In 1925, a revolutionary upsurge in China found expression both in mass strikes and in a broad student mobilization. When these two forces came together in joint action in Shanghai, they suffered a lethal attack by the British army, which claimed 52 Chinese fatalities. The International Red Aid, established by the Comintern in 1922, launched a vigorous protest. The campaign was headed by a gifted German Communist, Willi Münzenberg, who insisted on the need for effective educational work among masses of working people who were not yet Communist and not politically aware.

But could working people in Germany, who had suffered so much at the hands of the Treaty of Versailles, be persuaded to take an interest in the fate of the impoverished and despised masses of China?

‘Hands off China!’

Aiming to turn that hope into reality, International Red Aid founded the League against Colonialism, based in Berlin, to collect material aid for the working people of China. The League collected donations, explaining that an amount equal to the price of six cigarettes could cover the needs of a striking Chinese worker for a day. A conference in Berlin brought together more than 1,000 participants to demand, “Hands Off China!”

“We want to form a holy alliance, we, the white, yellow, black, and different-coloured underdogs… for the liberation of all those who suffer,” Münzenberg declared.(1)

Chinese socialists addressed workers meetings in Germany, while in Beijing a rally of 100,000 Chinese workers greeted a European socialist speaker with passionate enthusiasm. Thanks to the work of International Red Aid, working people of Europe and the Third World joined hands for the first time in opposition to colonialism.

Red Aid also campaigned at this time to aid Arab rebels in Syria and Morocco who were at war with the colonial powers, France and Spain. Red Aid mounted a broad campaign to denounce French massacres in Syria, where 10,000 Arabs were killed during French bombardment of Damascus. A broad, independent committee was formed to organize solidarity with Syria.

Material aid

Solidarity found expression not only through words but in practical terms. The Communist parties in France and Spain campaigned for independence for these countries’ colonies. The Communists encouraged soldiers in their countries’ colonial armies to fraternize with the rebels, and such incidents did occur. One deserter from the French Foreign Legion, for example, became an officer and strategist of the Moroccan rebel army. There were mutinies in the French navy, and 1,500 sailors faced courts martial. Meanwhile, 165 French Communists were imprisoned for anti-war activity. During this time, the Second International, made up of reformist socialists, still mostly abstained from anticolonial solidarity. The initiatives of Red Aid, by contrast, had become a genuine force in the political life of the colonial powers.

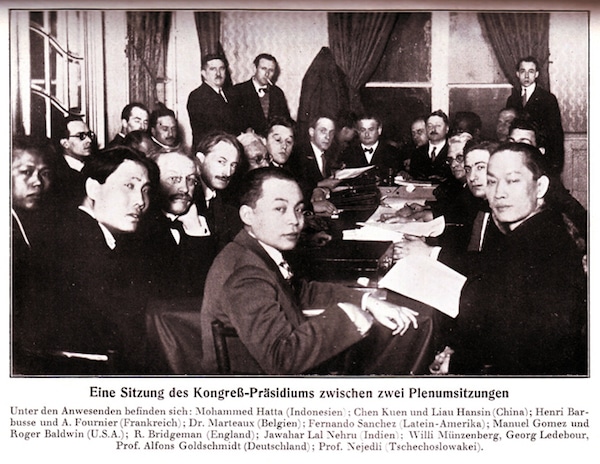

But these campaigns were still separate and temporary. How could they be brought together in a unified, ongoing effort? Achieving that goal was the purpose of the Congress against Colonial Oppression and Imperialism that gathered in Brussels, after extended delays by both the Belgian government and Comintern Executive, on 10 February 1927. The 174 delegates represented 134 organizations in 34 countries. The celebrated physicist Albert Einstein, honorary chairman, expressed the hope that “through your congress the efforts of the oppressed to win independence will take tangible form.”(2)

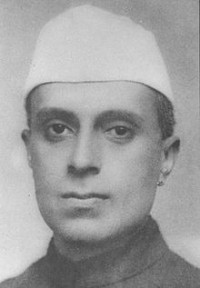

Among the delegates, in addition to revolutionary socialist leaders from many continents, were an array of prominent trade unionists from Europe, well-known leaders of the Second International’s left wing and representatives of influential bourgeois parties in the colonies, such as the Guomindang in China, the Sarekat Islam in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Jawaharlal Nehru of the Indian National Congress; and Raul Haya de la Torre’s APRA in Peru.

During six days of debate 16 reports were heard on tasks in different geographic regions and strategic aspects of anti-imperialist struggle. The second session proposed the foundation of the League Against Imperialism and National Oppression, which was to be an independent alliance with autonomous branches in countries around the world.

The German historian Kasper Braskén has summarized the message of the Congress in these terms:

Wherever on the planet there were proletarians living in misery, this would be a matter for the workers’ international solidarity, forging the belief in transnational workers’ community on a global scale.(3)

The League’s creation inspired enthusiasm beyond its founder’s wildest expectations. Historian Frederick Petersson tells us the Congress conveyed “the feeling of a spiritual bond and the expressions of collective joy”–a mood of “self-sacrifice and euphoria” that later, however, degenerated into “resignation and dejection.”(4)

Causes of decline

Despite the League’s initial momentum, the hopes of its founders did not become reality. Three years later, the League had lost its dynamic vigor and included only groups of Communists and their sympathizers. Rather than narrate this unfortunate decline, I will focus on its causes, and here I see three basic factors.

- The League was not a united front of the type proposed by the Comintern since 1921. True, it claimed to be autonomous and independent. The Comintern Executive Committee’s confidential instructions spoke of creating “a neutral intermediary between the anti-colonial movements and the Comintern.”(5) But in reality the League was administered by the Comintern apparatus concealed backstage. This contradiction was perceived by leaders of the Second International, who utilized it to force all their adherents in the League to resign.

- The united front that the Comintern proposed in Lenin’s time provided for an alliance with national revolutionary forces. Let me take a more recent example: the insurrectionary movement in Cuba led by Fidel Castro in the 1950s, which grew over time into a fusion of both national-revolutionary and socialist forces. By contrast, however, the movements linked with the League that I mentioned previously: the Guomindang, the Indian Congress, and Sarekat Islam, they were what Communists of the day termed reformist bourgeois movements.(6) Their representatives quickly withdrew from the League, and the Guomindang launched a murderous counter-revolution against Chinese workers. By Comintern principle, forming a temporary alliance with such bourgeois nationalist forces was certainly permissible, but structuring them into an organization of struggle such as the League was questionable, to say the least.

- A year after the foundation of the League, Comintern policies suffered a reversal linked to the onset of what Communists termed the Third Period. Despite all evidence to the contrary, the Sixth Comintern Congress in 1928 proclaimed that the world had entered a period of global revolutionary uprisings and overturns where it was wrong to form united fronts with non-revolutionary organizations. The Comintern went so far as to brand Social Democrats as representing a new form of fascism.The French historian Pierre Broué has commented that this policy was “an absolute guarantee of defeat,” referring to the triumph of Hitler in Germany in 1933. Willi Münzenberg opposed this ultra-leftist turn but was unable to block it. Given this new policy, Broué says, the League’s policies were “condemned to defeat” and, moreover, that “all its achievements were shattered by the abruptness of the turnabout and the abusive use of ultimatums.” All the non-Communist groups of any significance within the League resigned or were expelled.(7)>

After gaining power in 1933, the Nazis shut down the League’s Berlin-based headquarters and disrupted its operations. Munzenberg withdrew from the League that same year. The Comintern carried out another sharp policy reversal in 1935, and the League was formally disbanded two years later. Subsequently, the International worked for an alliance with supposedly progressive bourgeois forces in the imperialist countries – a goal that became known as the “popular front.” This orientation conflicted with Comintern efforts for colonial liberation. The Comintern itself was dissolved in 1943.

The League’s legacy

In balance, the League’s legacy is thus mixed. At its inception, it represented an influential expression of the Russian revolution’s anti-imperialist and anti-colonial spirit. The difficulties it encountered, in turn, reflected distortions of Soviet Communist policy as it entered the Stalinist era, when Comintern policy came to reflect the shifting exigencies of the bureaucratized and Stalinized Soviet state.

But that is not the end of our story. During and after World War 2, a number of countries in Asia shook themselves free of colonial domination. This overturn took place along two different paths. In a number of countries, such as India and Indonesia, the independence movement was led by bourgeois forces, and the independent state was capitalist in character. In China, Vietnam, and Korea, by contrast, the independence struggle was led by Communist parties formerly part of the Comintern, and the revolution ended in the abolition of capitalist rule.

The gains of this anti-colonial struggle found expression in 1955 in a historic conference in Bandung, Indonesia, attended by delegations of 29 decolonized countries of Asia and Africa, whose peoples made up an absolute majority of humanity. The resolutions adopted at Bandung proposed neutrality in the Cold War and the rapid elimination of all still-existing colonies. In his closing remarks at the conference, President Sukarno of Indonesia referred to the 1926 Brussels congress. It was the inspiration and sacrifices of the alliance formed at that time, he stated, that have made it possible “that we are now free, sovereign, and independent…. We do not need to go to other continents to confer.”(8)

The Bandung conference gave birth to a grouping of countries of the Global South, the Non-Aligned Movement, which played a modest but positive role in several contexts and which still exists. But to see an authentic reflection of the League Against Imperialism, we must turn, as my co-panelist Ameth Lô has suggested, to the initiatives of revolutionary Cuba, such as its participation in the anti-apartheid struggle in Africa or its more recent participation in ALBA, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America.

Almost a hundred years after the foundation of the League Against Imperialism, its liberatory spirit continues to find expression in new contexts and new forms.

A note on sources

Major sources for this talk include:

- Adi, Hakim, Pan-Africanism and Commuism: The Communist International, Africa and the Diaspora, 1919-1939, Trenton: Africa World Press, 2013.

- Braskén, Kasper, The International Workers’ Relief, Communism, and Transnational Solidarity: Willi Münzenberg in Weimar Germany, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Broué, Pierre, Histoire de l’Internationale communiste 1919-1943.

- Gross, Babette, Willi Münzenberg: A Political Biography, Lansing, Mich.: Michigan State University Press, 1974.

- Communist International, The First Congress of the Peoples of the Far East 1922, London: Hammersmith, 1970 (1922).

- Petersson, Frederick, We Are Neither Visionaries Nor Utopian Dreamers: Willi Münzenberg, the League against Imperialism, and the Comintern 1925-33, unpublished dissertation.

- John Riddell, ed., Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite! Proceedings and Documents of the Second Congress, New York: Pathfinder, 1991.

- John Riddell, ed., To See the Dawn: Baku 1920, First Congress of the Peoples of the East, New York: Pathfinder, 1993.

Footnotes

-

- ↩ Braskén, p. 160.

- ↩ Gross, p. 189.

- ↩ Braskén, p. 161.

- ↩ Petersson, p. 540.

- ↩ Petersson, p. 246

- ↩ The distinction between “national-revolutionary” and “bourgeois reformist” movements in the colonial world was explained by Lenin to the Comintern’s Second Congress in 1920 and shaped Communists thinking in the following years. There was disagreement among Communists, however, on whether the Guomindang was a “national-revolutionary” movement in the sense intended by Lenin.

The Guomindang’s counterrevolutionary attack on Chinese workers a few months after the Brussels conference proved that it was not “national-revolutionary” in this sense. For more on the evolution of Comintern China policy on this website, see “Should Communists Ally with Revolutionary Nationalism” and “Fruits and Perils of the ‘Bloc Within’.” For the Second Congress debate, see Riddell, ed., “Workers of the World and Oppressed Peoples, Unite,” vol. 1, pp. 211-90. - ↩ Broué, pp. 493-514.

- ↩ Petersson, p. 546, fn. 1272.