Donald Trump is a mercurial world leader. He seems to disdain the old order, the mechanisms of globalisation set up with great care by the imperialist bloc after the fall of the USSR and the Third World Project. On his second day in office, Trump signed an executive order to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and scrap the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). He followed up with tariffs on key commodities that would impact the European Union and China as well as Canada and Mexico.

The United States carries very large trade deficits. The U.S. trade deficit in goods and services for 2017 was $566 billion (the trade deficit in goods alone was $810 billion). The largest trade deficit is with China–$375 billion. Trump has said he wants to reduce these deficits through various protectionist measures–tariffs on steel and aluminum and on various Chinese goods.

Trump promised to ‘make America great again’. The slogan defined his campaign and his presidency. His bluster was often forgiven because of the sentiment attached to that slogan–it inspired a hope that Trump’s policies would protect the U.S. economy and ensure that the declining standard of living of Americans would be reversed. Two years into his presidency, there is little evidence of any improvement. Inequality continues to define the American economic landscape–CEOs, new government data show, can make up to a thousand times more in their salaries than their employees. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos makes $127 billion, the equivalent of what is held by 2.3 million Americans (he makes the median Amazon salary every nine seconds). It is impossible to suggest that high inequality should be the character of a Great America. Red hats with that slogan are easy to produce, but it is a bitter pill if these are made – as they often are – in Bangladesh, China and Vietnam.

At Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, we have wondered about the essential nature of these ‘trade wars’ that have broken out between key allies. Specificity is not always apparent in the discussions on tariffs. We turned to Prabhat Patnaik, Professor Emeritus at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning in the School of Social Sciences at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in New Delhi (India), for assistance. Prof. Patnaik is one of the leading Marxist economists in our times. He has authored a number of key texts, including Time, Inflation and Growth (1988), Economics and Egalitarianism (1990), Whatever Happened to Imperialism And Other Essays (1995), Accumulation and Stability Under Capitalism (1997), The Retreat to Unfreedom (2003), The Value of Money (2008), Re-Envisioning Socialism (2011) and (with Utsa Patnaik) A Theory of Imperialism (2016). Professor Patnaik was the Vice-Chairman of the Planning Board of Kerala (2006-2011) and is the editor of Social Scientist. He is a regular contributor for People’s Democracy.

The interview we conducted with him completes this dossier.

Hegemony of Global Finance

What is your first impression about the ‘trade wars’ initiated by Trump? Is this a serious policy shift or is there something else that we need to be aware of?

I believe that the whole discussion around Trump’s protectionist policies has been wrongly framed. The picture typically conveyed is of a villain called Trump suddenly unleashing a trade war upon an otherwise happy world. This is completely wrong. The entire capitalist world has been in the grip of a prolonged and serious crisis, which is the denouement of neo-liberalism. The liberal bourgeois establishment either does not recognize this crisis or does so only grudgingly. Trump recognizes it in his own fascistic way. He blames the ‘other’, that is, the Mexicans, the Chinese, and the Muslims, but not the system, for it. This very recognition on his part is the reason why the American people voted an unsavoury person like him to Presidency.

One cannot look at Trump and his policies in isolation from this crisis. Trump wants to resolve the crisis for America, caused by neo-liberalism, within the basic confines of neo-liberalism itself, i.e. without violating its core characteristic, which is free global mobility of finance.

The mechanism through which neo-liberalism has engendered this crisis should be clarified. Neo-liberalism has caused a global shift in income distribution from wages to surplus. Such a shift always creates an ex ante [before the event] tendency towards an over-production crisis in the world economy. This tendency was kept in check by the ‘dotcom’ and the ‘housing’ bubbles in the United States. The bursting of those bubbles one after another has made the ex ante crisis ex post [after the fact]. Since globalised finance frowns upon State intervention in ‘demand management’ advocated by Keynes, this crisis can be alleviated within the neo-liberal framework only through the formation of a new bubble. But such bubbles cannot be made to order; and, even if they do get formed, they inevitably collapse, precipitating a crisis once again.

Trump is trying to break out of this situation by enlarging the fiscal deficit, which the United States can do with some impunity because of its currency being considered ‘as good as gold’ (and also additionally because it has raised its interest rate recently with the promise of more to come, which is sucking in finance from all over the world to the United States); but if this demand stimulus is not to ‘leak out’ and result merely in creating employment elsewhere at the expense of a larger U.S. external debt, then protectionism becomes necessary for the United States.

Trump’s therefore is not just some crazy intervention in an otherwise benign liberal order; it represents a coherent policy. This policy however would not work because it amounts to a ‘beggar-my-neighbour’ policy and assumes erroneously that other countries would not retaliate.

Trump’s suggestion to other metropolitan countries of course is not to retaliate, but rather to boost their own economies through their own larger military spending. But such spending on their part would aggravate the flight of finance from their economies, eliciting a rise in their interest rates, which would negate any boost to their activity. In the absence of any such boost therefore, instead of simply losing out to U.S. protectionism, they themselves therefore would go protectionist, thereby frustrating Trump’s strategy.

I see the tariffs essentially as a response to the crisis within the United States whose seriousness must not be underestimated, though they of course have other simultaneous effects. To mention just one indicator of the acuteness of the crisis, the death rate among male white American workers in recent years has been high, higher than that of any other Western country not engaged in war. This high death rate arises from the insecurity and loss of self-esteem that always accompanies unemployment, which pushes people towards drug and alcohol-abuse.

There are some that believe that automation is the cause of this crisis. Automation, or more generally labour-saving technological progress, is a perennial feature of capitalism, which is invariably afflicted by unemployment. But globalisation has certainly worsened the unemployment situation in the U.S. through U.S. capital’s relocation of production facilities to lower-wage regions of the world.

Linked to that question, do these manoeuvres by Trump represent a lasting shift in the current ‘free-trade’ system or do they merely represent a temporary, electoral detour?

To see these policies as a temporary electoral detour is to underestimate the capitalist crisis, which is also an existential crisis for the system–of which the current upsurge of fascism is a manifestation. The system cannot go on as it has been doing. Trump thinks that by modifying ‘free trade’ but keeping ‘free flows of finance capital’ intact, the system can be rescued. This is wrong because there can be no global economic expansion in the current world of nation-States without capital controls being put in place.

But Trump seems to be implicitly aware at least of the need for a lasting shift which he is attempting, while his liberal critics see his actions merely as gratuitous and capricious.

Trump and his advisors believe that these policy shifts will help the U.S. recover the U.S. manufacturing jobs that have been lost over the past thirty years. Do you think it is possible for the U.S. to recover these jobs?

The Trump strategy might work if other countries accepted Trump’s ‘beggar-my-neighbour’ policy. But they obviously would not. Hence while it may appear for the moment that the strategy is working, matters will change when others retaliate. And when they do, the very fact of a ‘trade war’ will dampen capitalists’ inducement to investment in the world economy, and thereby further aggravate the crisis.

You have been critical of the view that this new trade war might produce ‘de-globalisation’. Why do you believe that this apparent retreat from the global system will not produce the potential for autarky?

To me the essence of the current globalisation is globalisation of finance. It is in this respect that it is different from all previous episodes of globalisation, and has a profound impact on the nature of the State: The State which remains a ‘nation-State’ is forced to accede to the demands of globalised finance (for otherwise there would be capital flight from the country in question and a financial crisis in it). Even if there is protectionism in the movement of goods, that per se would not change this fact of the hegemony of globalised finance one iota. No metropolitan leader to date has talked of imposing capital controls; so, all this talk of ‘de-globalisation’ in my view lacks validity.

China and the United States

Raghuram Rajan, former Chief Economist at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, once said that China and the United States are in a ‘satanic embrace’ and that their inter-relation is unstable and dangerous. Do you concur with this view?

I do not accept the terms of this discourse. It is American capital that has relocated production to China to make larger profits. So, it is not a question of ‘America versus China’ but of ‘America versus American capital’. Because of the social distress and anger in the U.S. that this has generated, especially during the current prolonged economic crisis, Trump is trying to curb to an extent American capital’s incentive for relocation of production abroad through his protectionism, but not the free movement across the globe of American, or more aptly, international finance. And for the loss that would accrue to American capital on account of this protectionism, he is offering compensation in the form of substantial corporate tax-cut s. I, therefore, foreground American capital in my analysis.

Will the performance of the seemingly flat U.S. economy have an impact on policy in China? What do you foresee as the Chinese reaction to the Trump feint–apart from the first reaction, which was to raise their own tariffs?

It is obvious that, apart from raising its own tariffs, China now has to rely more on its internal market to sustain the tempo of its growth. This would require greater government expenditure, a higher rate of agricultural growth, and a more egalitarian distribution of income within China. These are the policies associated traditionally with socialism (assuming that government expenditure is on education, health and social services). The adjustment that Trump’s measures would force China to make could thus have the effect of pushing China more towards socialist policies. This, in my view, would be most welcome.

China has a great advantage in this regard, namely that it can make a transition towards such home-market-oriented policies at very little cost. This is because, unlike India, it has never been fully open to unrestricted financial flows anyway, so there is no question of any capital flight during the transition. And also, unlike India, it has a current account surplus on the balance of payments, so that no problem of financing a current deficit during the period of transition would plague China.

In my view, the opposition to such a transition towards more egalitarian policies is likely in my view to be political, on account of pressures from the burgeoning Chinese urban middle class which, like its Indian counterpart, the Chinese urban middle class always eyes opportunities in the West, has been a major beneficiary of China’s rapid growth, and has an anti-egalitarian bias.

Dollar Imperialism

Some years ago, Peter Gowan wrote of the Dollar-Wall Street Regime and of Dollar Seigniorage–where the dollar and Wall Street reinforced the power of each other and where dollar seigniorage allowed the U.S. to run up large deficits as well as allowed the U.S. financial system to become the world’s main source of credit. Does this system remain alive today?

Despite Trump’s announcement of protectionist policies and an increase in the fiscal deficit, the United States, which would normally have weakened the dollar, is sucking in finance from all over the world. This dynamic leads to an appreciation of the dollar. True, there has been an increase in U.S. interest rates with further increases in the offing. But this suggests to me that the role of the dollar as the stable medium of holding wealth in the world economy remains unimpaired. And the unimpaired power of the dollar also entails the unimpaired power of Wall Street.

Do you believe that if Trump continues this policy direction, there might be renewed seriousness about the role of the dollar as the principal currency in the world and of the role of Wall Street as the main source of credit?

The role of the dollar, and with it the associated role of Wall Street, arises because the capitalist world economy requires a stable medium of holding wealth, and there is no other currency that can play this role at present. The Euro, which was always secondary to the dollar but appeared for a while to pose a potential challenge to it, has lost its strength.

Of course any individual agent’s confidence in the stability of a currency arises from the fact that he or she believes that everyone else believes in this stability. In other words, there is in other words a herd instinct about it, but this herd instinct is not arbitrary, that is it cannot attach to just any currency. For a currency to qualify as being considered ‘as good as gold’, it must have certain characteristics. The country to which it belongs must ensure within its territory the security of capitalist property relations. It must also be powerful enough to ensure, through its interventions, including military interventions, the security of capitalist property relations elsewhere. It must likewise be able to prevent any inflationary threat to its currency (so that people do not shift from their currency to actual gold, that is their currency must remain ‘as good as gold’) by maintaining an adequate reserve army of labour and imposing ‘income deflation’ on primary commodity producers through a global economic regime, backed by its military might. And so on. It must, in other words, be the leading imperialist power, the bastion or home base of world capitalism. The U.S. continues to remain just that, which is why its currency is considered ‘as good as gold’, notwithstanding all its economic travails and policy shifts. It will remain so for the foreseeable future.

It is ironic that after the collapse of the housing bubble when a financial crisis broke out with the U.S. at its epicentre, finance from all over the world flowed into the U.S. rather than out of it. It was like making a beeline for your home base when you are panic-stricken. Likewise, today there is a similar flooding of finance into the United States. Its being the home-base for capital is thus linked to deeper factors than just its specific policies or performance.

Alternatives?

What could progressive governments do to make room for themselves in this context? What, for instance, should the new government in Mexico do to create space for a social democratic agenda? What financial policies would you advise in this context, in other words?

I believe that any government pursuing pro-people policies will sooner or later have to introduce controls over cross-border financial flows. The reason is obvious: it will either have to listen to finance or to the people, and if it does the latter then it will incur the wrath of finance, to counter which it will have to control financial flows. But I think governments such as López Obrador’s in Mexico, instead of shouting from the housetops their intentions to impose capital controls, should first move towards adopting pro-people policies, and, when finance opposes such policies through capital flight, to impose capital controls. In other words, the government’s action must appear to all as being necessitated by the caprices of finance rather than being just ideologically driven.

You note that the globalisation of finance remains alive despite this protectionism. How might a progressive government raise funds for an alternative agenda in this protracted period of the globalisation of finance?

One has to draw a distinction here between finance and savings. Finance per se is never a problem for any country, unless it ties its own hands by doing away with the Central Bank (as in Eurozone countries) or giving full autonomy to it, which means in effect that it is run by Fund-Bank officials. As long as capital flight is prevented through capital controls and democratic control over the Central Bank is retained, there is no financial problem that any progressive government would face.

The real problem however relates to savings, and these can be mobilized by any progressive government that wishes to adopt pro-poor policies through taxing the rich, who have become far richer in this period of globalisation. In a country like India for instance where the top 1 per cent of the households owns 60 per cent of the total wealth, a ratio that has increased dramatically over the period of neo-liberal policies and continues to do so even now, there is no wealth tax worth the name, which is scandalous. The same is true more or less in other countries as well.

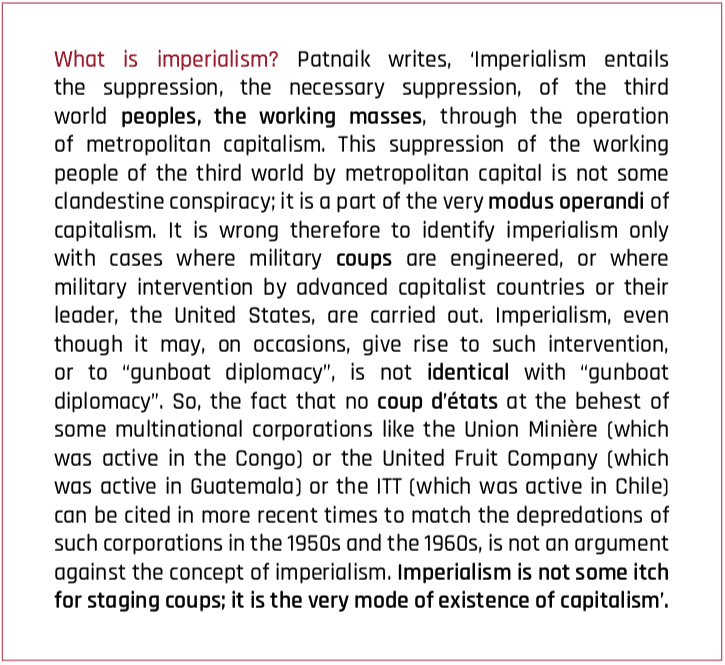

Hence the difficulties faced by a progressive government arise not because of any objective economic constraints it faces, but because of the might of world imperialism, which has to be seen today not just in terms of American or German or Japanese imperialism but as the imperialism of international finance capital.