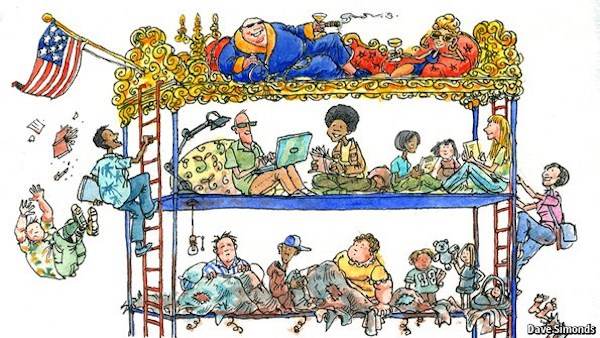

Legal advocates have scored some major class-related victories in 2018. In January, an appellate court held that the administration of California’s money bail system violated the Fourteenth Amendment rights of indigent defendants. In February, the Fifth Circuit held Harris County’s money bail procedures unconstitutional on the ground that they keep the “poor arrestee” behind bars “simply because he has less money than his wealthy counterpart.” But holdings that explicitly vindicate the constitutional rights of people without financial resources remain rare, and that rarity bolsters the widespread perception that Fourteenth Amendment law offers virtually no protection against class-based discrimination.

It is true that class-based discrimination does not trigger heightened scrutiny under equal protection in the way that race-based and sex-based discrimination do. Fifty years ago—in the era of Gideon v. Wainwright and Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections—it looked to many as if the Court was poised to recognize the poor as a protected class (or perhaps, as Frank Michelman famously argued, to recognize a constitutional right to some form of minimum welfare). But in San Antonio v. Rodriguez and the abortion funding decisions, the Burger Court both declined to recognize the poor as a protected class and rejected the idea that the Constitution guarantees minimum welfare.

Scholars have often viewed those decisions as excising all class-related concerns from Fourteenth Amendment law. But that view has obscured an important and ongoing form of class-related constitutional protection: one that resides not in equal protection but in fundamental rights doctrine. My new article (The New Class-Blindness, forthcoming in the Yale Law Journal) examines the long-standing and often overlooked forms of class-related constitutional protection the Court has developed in the fundamental rights context. These protections have played an important role in some areas of Fourteenth Amendment law for over half a century. But they are now under attack by conservative judges, who have begun to argue, for the first time, that it is impermissible for courts to consider class at all when adjudicating Fourteenth Amendment claims.

What forms of class-conscious constitutional analysis survived the Burger Court’s rollback of equal protection doctrine? One example is the undue burden test the Court uses to assess the constitutionality of abortion regulations. To determine whether an abortion regulation is constitutional, the Court asks whether it imposes an undue burden on the subset of women who are actually affected by it—a group that in many cases consists of women without financial resources. If a regulation unduly burdens those women’s rights, it is unconstitutional—even if it does not unduly burden the rights of wealthier women.

The Court has developed a similar test in the context of voting. For instance, in cases involving voter ID laws, it asks whether the ID requirement unduly burdens not the average voter, but those voters for whom the requirement actually constitutes an obstacle. And, of course, there are numerous criminal procedure cases still on the books in which the Court protects rights essential to equal justice for indigent defendants. Occasionally, the Court even expands this line of cases.

It should not be surprising that fundamental rights doctrine continues to protect the financially disadvantaged despite the Court’s pronounced shift to the right in the 1970s. Concerns about class helped to drive the Court’s recognition of a number of key fundamental rights in the first place; such concerns were thus embedded in the marrow of fundamental rights doctrine from the start. It is easy to see how class-related concerns motivated the Court to require the government to provide indigent criminal defendants with lawyers and trial transcripts. But, my new article shows, such concerns also informed the Court’s decision to recognize birth control and abortion as fundamental rights. The struggles of poor women—and the very real dangers they faced as a result of the criminalization of birth control and abortion—helped Americans in the 1960s and early 1970s to recognize how such bans deprived people of equal citizenship and encroached on the basic forms of liberty the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to protect.

The Burger Court was not willing to extend heightened scrutiny to all class-based discrimination, or to require the government to provide its citizens with affirmative welfare benefits. But it did not excise all class-related concerns from Fourteenth Amendment law. Although the Court has narrowed some of the protections it affords fundamental rights, it has never held—never even suggested—that class-related concerns are irrelevant to the constitutionality of laws that impinge on such rights.

Today, however, these remaining forms of class-based constitutional protection are under threat from what I call “the new class-blindness.” Some judges—even some Supreme Court Justices—have begun to argue that it is constitutionally impermissible for courts to take class into account under the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fifth Circuit reached this conclusion a few years ago in the Whole Woman’s Health case, in which it asserted that judges could consider only obstacles created by “the law itself” when determining whether a law unduly burdens the right to abortion—a category that excluded obstacles such as lack of transportation, childcare, days off from work, and money for overnight stays. When Whole Woman’s Health reached the Supreme Court, some of the Justices (in dissent) expressed support for this approach.

A number of Justices have also expressed support for this class-blind approach in the context of voting rights, asserting that courts in voter ID cases should ask whether the law imposes an undue burden on the average voter (who, of course, already possesses a government-issued ID). In both the reproductive rights and voting rights contexts, judicial advocates of the new class-blindness cite Burger Court precedents in support of the proposition that it is illegitimate to take class into account under the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, Justice Thomas has argued that a good number of the Warren Court’s criminal procedure decisions are no longer good law for this reason: they took account of class in a way the Court later rejected.

This is a misreading of the law. The Burger Court certainly narrowed class-based constitutional protections. But it did not hold that class is irrelevant where fundamental rights are concerned. Indeed, the opposite is true: The Court has consistently preserved doctrinal mechanisms for taking class into account in the area of fundamental rights. Thus far, a majority of the Justices have rejected the new class-blindness in every context in which it has arisen.

Whether the Court will continue to resist these increasingly insistent efforts to dismantle class-related fundamental rights protections remains to be seen. Ultimately, the fate of these efforts depends on constitutional politics, and it is not entirely clear how those politics will develop over the coming decades. What is clear is that the emergent notion that class-based considerations have no place anywhere under the Fourteenth Amendment is a product not of the Burger Court era, but of our own.