Ten years since financial markets crashed in the United States (U.S.), the world economy is anything but near so-called “recovery.” Far from it: global economic growth is still slower since the crisis. Investment, which includes flows of capital for new production and for buying up other companies, declined for 2017.1 Global unemployment is estimated at 192 million for 2018.2 “Global value chains”, production networks controlled by transnational corporations (TNCs) which benefit from lower labour costs, are said to be slowly declining.3 Economies in the global South are threatened with the possibility of debt crises that could unravel in the next years.

If anything, the 2008 financial crash exposed to the public the faults in the neoliberal policy that had been promoted for at least four decades by U.S.-dominated international finance institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group (IMF-WB).

With liberalised and de-regulated finance, the market for various and complex “financial products” grew in the last decades—resulting unstable bubbles of speculation had burst in the early 2000s and again in 2008. With Southern economies opened up to varying degrees by neoliberal policy, TNC-led “value chains” emerged to maximize cheaper labour, production costs and inputs.

Today’s huge global debt, and especially debt in the global South, is still linked to the U.S. and other central banks’ “response” to 2008. These banks “printed” more money to lower interest rates which, among other effects, later led big private corporate lenders to run after Southern countries with the higher interest rates and therefore higher returns for lenders.

At global level, debt was at 225 per cent of GDP in 2015. As the U.S. central bank recently raised its interest rates and lenders looked to flow their money back into the U.S., these Southern economies are increasingly threatened with debt crises. August 2018 IMF assessments point to seven (7) low-income countries already in “debt distress,” and 24 were considered at “high risk”.4

Meanwhile, the rise of off-shore production and related activities in the last decades generated greater financial revenues and profits for TNCs’ shareholders, which in many cases were at the expense of humane working conditions and Southern people’s rights. Almost 70 percent of employed in developing countries work “informal” jobs in 2017—which include employees without social and labour protection, those working in farms unregistered in governments, temporary workers, among others.5 Among developing country workers, there are also an estimated 713 million who live below USD 3.10 per day (which remains a conservative measure for living standards). 6

Concerns have indeed been raised against the official policy discourse that purports “global value chains” as key for development.7 As a central aspect of neoliberal “globalisation,” concern mounts as the growth in off-shore production stagnates,8 and has been considered by the WTO as a factor in slower GDP growth.9

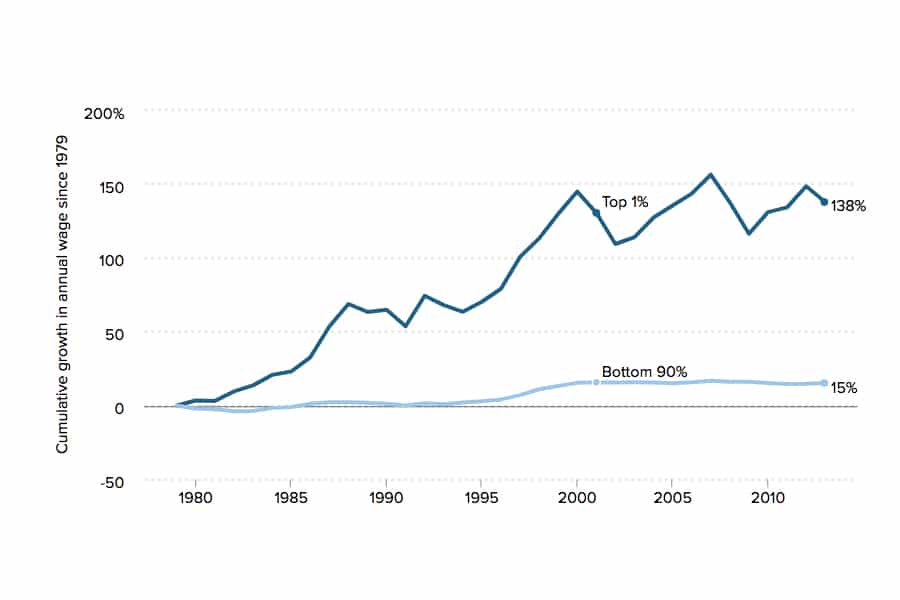

As corporate profits and monopoly power continue to rise since 2008, even a former IMF chief links current worsening inequalities10 to the re-emergence of right-wing parties in Europe,11 as well as the right-wing “populism” that currently trumps politics in the U.S. Informal jobs in U.S. and Canada account for 18 percent of those employed, and 16 percent for developed countries Europe and Central Asia.12 Wages in the U.S. have mostly remained stagnant for years.13

Source: EPI analysis of data from “Earnings Inequality and Mobility in the United States: Evidence from Social Security Data Since 1937,” by Wojciech Kopczuk, Emmanuel Saez, and Jae Song, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 2010; updated through 2013 with data from the Social Security Administration Wage Statistics database. Reproduced from Figure F in Raising America’s Pay: Why It’s Our Central Economic Policy Challenge, by Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, Lawrence Mishel, and Heidi Shierholz, Economic Policy Institute, 2014.

In this way, the 2008 “crisis of neoliberalism” continues in a protracted fashion today; and this is also part of a longer history of crises and the longer trend of slowing economic growth even in industrialised countries of the current world economic system.

Research by multilateral institutions is even beginning to admit the faults of neoliberalism (to varying degrees). A 2018 UNCTAD policy brief laments that “market power” is a strong factor in income inequality—as “surplus profits” from “rentierist profit strategies” consist of ever larger parts of operating profits among the biggest corporations, mainly within sectors that experienced privatisation.14

Meanwhile an IMF working paper showed that since the 1980s, and even more since 2008, there is growing corporate market power among biggest companies in industrialised countries. The shares of revenue that went to profits had increased throughout the period while the share going to workers have declined.15

Among others, a “global New Deal” has been proposed. The proposals predictably involve greater regulation but resist any suggestion of changing the fundamental character of the profit-driven world economy dominated by monopolistic, international capital. These efforts are nakedly concerned only with saving the world economy until the next crisis, and in that sense merely repeat and intensify patterns of action established by neoliberalism, which emerged during crises in the 1970s.

Most urgent today is the need for fundamental social and economic reforms at both national and international levels. The membership of Southern countries in the IMF-World Bank as well as the WTO should be reviewed and re-examined given its effects on people’s rights.

For Southern countries, people’s sovereignty—meaning the active participation of people’s and grassroots organisations—must be an essential premise for those committed to establishing development policies that actually benefit those at the bottom. This principle could serve to ensure that policy direction is actively led by the grassroots organisations—instead of being dominated by the IMF-WB and WTO prescriptions—so that long-standing demands, and broad social and economic rights, can be attained by the working classes. This could be, for instance, towards greater public spending for strategic industrial development, rural development and agrarian reform.

With people’s sovereignty as a key guiding principle, various policy tools could be utilised. For example, establishment of controls of the flow of capital, regulation of foreign investment and foreign borrowing; repealing taxes that put burden on the poor with corresponding progressive taxation of domestic elites and TNCs; halting “transfer-pricing” and other illicit financial flows; the re-examination of current Southern government debts for possible cancellations; budget re-allocations away from military spending; and even the use of monetary policy targets pegged not on inflation targets but on employment and towards greater equality.

This would mark an important step toward the goal of economies oriented to need and governments capable of carrying out democratically-led development strategies—instead of filling up the pockets of financial executives, big shareholders, corporate managers and elites in governments.

Notes

- ↩ UN Conference on Trade and Development. 2018. World Investment Report 2018: Investment and New Industrial Policies.

- ↩ International Labour Organization. 2018a. World Employment and Social Outlook 2018: Trends.

- ↩ UN Conference on Trade and Development. 2018. World Investment Report 2018: Investment and New Industrial Policies.

- ↩ International Monetary Fund. August 2018. “List of Low-Income Countries Debt Sustainability Analysis for Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust-Eligible Countries.”

- ↩ International Labour Organization. 2018b. Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture.

- ↩ International Labour Organization. 2018a. World Employment and Social Outlook 2018: Trends.

- ↩ Carballa Smichowski, Bruno, Cedric Durand andSteven Knauss. 2016. “Uneven development patterns in global value chains. An empirical inquiry based on a conceptualization of GVCs as a specific form of the division of labor.” Working Paper.

- ↩ UN Conference on Trade and Development. 2018. World Investment Report 2018.

- ↩ World Trade Organization. 2017. Global Value Chain Development Report 2017: Measuring and Analyzing the Impact of GVCs on Economic Development.

- ↩ Rodriguez, Antonio. “World unprepared for next financial crisis: Ex-IMF chief.” The Jakarata Post. 9 September.

- ↩ BBC News. 2018. “Europe and nationalism: A country-by-country guide.” 10 September.

- ↩ International Labour Organization. 2018a. World Employment and Social Outlook 2018: Trends.

- ↩ Mishel, Lawrence, Elise Gould and Josh Bivens. 2015. “Wage stagnation in nine charts.” Economic Policy Institute.

- ↩UN Conference on Trade and Development. 2018. “Corporate rent-seeking, market power and inequality: Time for a multilateral trust buster?” UNCTAD Policy Brief 66, May. http://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/presspb2018d3_en.pdf

- ↩ Diez, Federico and Daniel Leigh. 2018. “Chart of the week: The rise of the corporate giants.” IMF Blog. June 6.