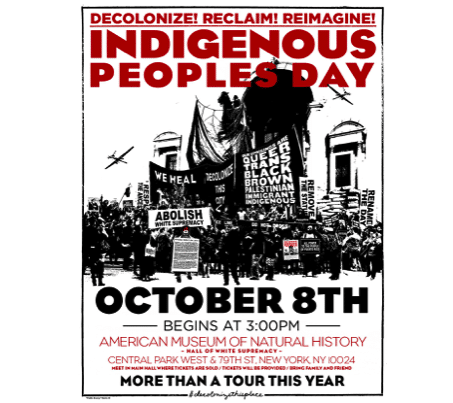

On October 8th, we will be returning to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) for the third year in a row. Unlike the guided anti-Columbus tours of previous years, the next visit to the museum’s dusty cultural halls will be fully participatory and will culminate with a People’s Assembly. Why the change of plan?

Since our first action in 2016, the concept of “decolonizing museums” has entered the mainstream of public opinion. Awareness about the topic has also gone international, impacting museums in the UK and Europe faced with similar challenges to the AMNH. Clearly, the public appetite for pro-active change has grown in scope and urgency, and museum officials have been scrambling to respond. Despite our city’s preferred self-image as on the cutting edge, New York’s major museums have barely registered this seismic shift, and the AMNH, which has the most heavy lifting to do, risks being left even further behind—solidifying its reputation as a chronically outdated institution, crammed with deeply colonial and faulty representations of culture. While the framing of these contents is firmly rooted in the distant past, the exhibits perform the daily work of reinforcing racist legacies that reside in the minds of the AMNH’s visitors.

So, too, the closed room conversations we have conducted periodically with AMNH curators and officials seem to have run their course. Those we meet with are usually always in agreement with us about the need for a decolonization process (with full attention to demands for reparations and repatriation of human remains and sacred objects) but we feel the oppressive weight of institutional inertia in the room, and the responses are too measured and painfully slow in coming. In a recent correspondence with us, the AMNH acknowledged the problem: “We recognize that the Museum’s 150-year history and that of its collections are embedded within the larger history…of western colonization….We also recognize that some aspects of the Museum’s cultural halls are out of date and include presentations and treatments that do not accurately represent either the cultures presented or the values and perspectives of the Museum today.” Accordingly, the AMNH has finally begun its overhaul of the Northwest Coast Hall. But, at the current rate of progress, it will take another fifty years to re-do all of the cultural halls. In the meantime, the cultural violence will continue, and generations of young people will be exposed to the harms generated by degrading representations as they pass through the museum.

As part of our children’s education, they have a right to know the full story behind the collecting and the exhibiting of the museum’s contents. They should be told how and why the AMNH was the center of the eugenics movement in the early part of the twentieth century. They should learn about the real Teddy Roosevelt, strenuously driven, as he was, by the ideals of male chauvinism and white supremacy, and how those socially destructive values were, and still are, embedded in the museum’s classification and framing of materials. They should be informed about the ongoing contribution of these misbeliefs to present-day racism, sexism, and homophobia. They should be prompted to ask why the museum only exhibits the culture of non-Euro/settler peoples i.e. the colonized populations of the world. And, ultimately, they should be encouraged to consider why such cultural halls belong in a museum of natural history at all.

The AMNH likes to describe itself as an educational institution, but there is nothing in the museum that would inspire schoolchildren to ask such questions, even though hundreds of thousands are required to visit annually as part of the New York public school curriculum. As for higher education in the AMNH’s would-be peer institutions, the museum tends to feature only in college curricula as a case-study in colonial nostalgia. In our universities, course syllabi are constantly being amended to reflect new schools of thought and breakthroughs in historical knowledge. By contrast, most of the museum’s dioramas and exhibits have not been altered in many decades, and many are untouched since they were installed a hundred years ago.

Nor has the museum lent its influential voice to the two other causes we have brought to its doors.

1) It has been silent on the issue of renaming Columbus Day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and it has yet to move forward on the acknowledgement that its building sits on occupied Lenape territory—a decision wholly under its own control. We have condemned this position of non-advocacy and this reluctance to adopt a Territorial Acknowledgement as aggressive actions against Indigenous peoples. We have demanded that the museum take immediate steps to remedy the harms.

2) In the course of the debate generated by the Mayor’s commission to review “symbols of hate” in New York City, the AMNH made no public comment on the fate of the equestrian statue of Theodore Roosevelt which greets visitors to the museum on Central Park West. The commission was split over the decision to remove the monument—a full half of its members voted for its relocation. Given how integral the statuary and hagiography of Roosevelt is to the AMNH, the museum should have taken on its share of responsibility for addressing the Monument’s future rather than punting the decision wholly to the City. Its officials have privately described to us their shame at having to pass by the monument every day, and the time is now long overdue for them to address their “Roosevelt problem.” We have demanded that the AMNH leadership publicly state its resolve to rethink this deeply flawed adoration of Roosevelt, which confronts visitors at the entrance and which is further imposed on them inside the museum itself, in the lavish homage on display in the Theodore Roosevelt Rotunda and the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Hall.

The museum is not a private institution, it relies heavily on public funding (upwards of $17 million annually), and so we all have a right to insist on accountability. As people gather on October 8th, we will ask them to help reclaim the space of the halls through self-organized tours and to imagine a different kind of institution. The assembly to follow will feature reports and testimony from these tours. We will acknowledge the decolonial proposals presented over the last two years, and consider the museum’s responses, as outlined above. With these in mind, the assembly will formulate new demands, for adoption by those present. Participants will pledge to pursue these demands with the AMNH’s senior officials and board members, and with elected city officials who are ex officio trustees.

Decolonize This Place

NYC Stands with Standing Rock

Signatories: American Indian Community House, Black Youth Project 100, South Asia Solidarity Initiative, Chinatown Art Brigade, Take Back the Bronx, The People’s Cultural Plan