John Pilger is one of the world’s acclaimed investigative journalists and documentary film-makers. He is a leading critic of the foreign policies of the United States and the United Kingdom, imperialism, war, racism, neoliberalism, atrocities against indigenous people and the corporatisation of the media. In his journalism career of six decades, Pilger has documented, with prescience and precision, how the world order is shaped by the interests of powerful nations. Based in the U.K. since 1962, he has made 61 documentaries capturing some of the most important events and episodes of the second half of the 20th century and the present century. These include the Vietnam war; the turmoil in Cambodia; Indonesia’s genocide in East Timor; the U.S.’ intervention in Latin American countries, Afghanistan and Iraq; the Israeli occupation of Palestine; and the impact of the policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on Third World countries.

Pilger made his first documentary, The Quiet Mutiny, in 1970. The landmark film was about a hitherto unreported rebellion sweeping the U.S. military in Vietnam. His reports from Cambodia in the immediate aftermath of Pol Pot’s reign for Daily Mirror, London, and a subsequent documentary, Year Zero: the Silent Death of Cambodia, alerted the world to the stricken state of the Cambodian people and helped raise more than $55 million for that country. His documentaries Death of a Nation: The Timor Conspiracy (1994) and Flying the Flag, Arming the World (1994) and written reports significantly contributed to drawing world attention to the horrors of occupation by Indonesia in East Timor. His documentaries on Australia, notably The Secret Country (1983) and a trilogy, The Last Dream (1988), Welcome to Australia (1999) and Utopia (2013), revealed much of his own country’s “forgotten past”, especially the struggles of its indigenous people. In The War on Democracy (2007), he revealed the scale of U.S. intervention in the political and economic processes in the Latin American countries. In The War on Democracy, he observes: “Since 1945, the United States has attempted to overthrow 50 governments, many of them democracies. In the process, 30 countries have been attacked and bombed, causing the loss of countless lives.” His latest documentary, The Coming War on China (2016), captures the current U.S. obsession with China.

Beginning his career in 1958, he has worked for Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror, Reuters, News on Sunday and the Independent Television Network (ITV). He has contributed to various international publications and news services, including The Guardian, The Independent, The New Statesman, The New York Times, BBC World Service, ABC Television, Al Jazeera, Russia Today, The Los Angeles Times, TruthOut, Antiwar.com, and Consortiumnews.com. As a journalist, he is well known all over the world for his dissenting voice and professionalism. On the duty of a journalist, he says: “It is not enough for journalists to see themselves as mere messengers without understanding the hidden agendas of the message and myths that surround it.”

Pilger has authored several books. They include Freedom Next Time, Tell Me No Lies: Investigative Journalism and Its Triumphs, The New Rulers of The World, Heroes, Hidden Agendas, Distant Voices and A Secret Country.

He has received prestigious awards and honours, including Emmy (American Television Academy Award) and BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) awards, both in 1991, for his documentaries; and the Royal Television Society’s award for the best British documentary. In 2003, he was awarded the prestigious Sophie Prize for “30 years of exposing injustice and promoting human rights”. In 2009, he was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize. He is also the recipient of the United Nations Association of Australia’s Media Peace Award in 1979. He was one of the youngest persons to receive Britain’s “Journalist of the Year” award in 1967. In 2017, the British Library archived Pilger’s works, including hundreds of news reports, films and radio broadcasts from his personal collection.

In this first substantial interview to any Indian media, Pilger speaks on issues such as U.S. aggression in the Asia-Pacific region, the decline of the U.S. global dominance, Barack Obama’s presidency, the war on democracy, WikiLeaks’ revelations, the changing media landscape in the digital era, the political economy of war, Vietnam, the global war on terrorism, West Asia, neoliberal capitalism, Brexit and journalism. Excerpts:

Your recent documentary, “The Coming War on China”, exposes how the U.S. is at war with China. Could you explain the mechanism of this secret war? Do you think that the Asia-Pacific will be the next region of imperialist intervention? How will this intervention unfold and what will be the fallout?

It is a “secret war” only because our perception is shaped to ignore the reality. In 2010, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton flew to Manila and instructed the newly inaugurated Philippines President Benigno Aquino to take a stand against China for its occupation of the disputed Spratly Islands and to accept the presence of five rotating U.S. Marine bases. Manila had been getting along fine with Beijing, having negotiated badly needed soft loans for infrastructure. Aquino did as he was told, and agreed to accept a U.S.-led legal team to challenge China’s territorial claims in the Spratlys in the U.N. Court of Arbitration in The Hague. The court found that China had no jurisdiction over the outcrops of the Spratlys; a judgment China rejected outright. It was a small victory in a U.S. propaganda campaign to portray China as rapacious rather than defensive in its own region. The motive lay in the growing insecurity of America’s national security/military/media elite that it was no longer the world’s dominant power.

In the following year, 2011, President Obama declared a “pivot to China”. This signalled the transfer of the majority of U.S. naval and air forces to the Asia-Pacific region, the biggest movement of military material since the Second World War. Washington’s new enemy—rather, renewed enemy—was China, which had risen to extraordinary economic heights in less than a generation.

The U.S. has long had a string of bases around China, from Australia through the Pacific Islands, to Japan and Korea and across Eurasia. These are currently being reinforced and modernised. Almost half of America’s worldwide network of more than 800 bases ringed China, “like the perfect noose”, commented a State Department official. Under cover of “the right of freedom of navigation”, U.S. low-draught ships intrude into Chinese waters. U.S. drones overfly Chinese territory. The Japanese island of Okinawa is a vast U.S. base, with its contingents prepared for an attack on China. On the Korean island of Jeju, Aegis-class missiles are aimed at Shanghai, 400 miles away [640 kilometres]. The provocation is constant.

South Korean soldiers and U.S. Marines from III-Marine Expeditionary Force from Okinawa, Japan, ski during their joint military winter exercise in Pyeongchang, South Korea, on December 19, 2017. Photo: Ahn Young-joon/AP.

On October 3, for the first time since the Cold War, the U.S. threatened openly to attack China’s closest ally, Russia, with whom China has a mutual defence pact. There was little media interest. China is arming rapidly; according to specialist literature, Beijing has changed its nuclear posture from low alert to high alert.

People like Noam Chomsky say that the American empire is on the decline. Do you think so? In recent times we have seen the U.S. trying to reach some kind of agreement with North Korea; earlier it had tried to re-establish diplomatic relations with Cuba. What do these episodes indicate? Do you think that the world is becoming more diverse?

The American empire as an idea may be in decline, along with the assumption of a sole overarching power and the dollarisation of the world economy, but the U.S. military might has never been more threatening. A new Cold War beckons isolation for the U.S. and danger for the rest of us. At the beginning of the 21st century, [the American journalist and novelist] Norman Mailer wrote that American power had entered a “pre-fascist” era. Others have suggested we are already in it.

This picture taken in 1954 shows Vietnamese soldiers resting between two advances in a trench at Dien Bien Phu. The fighting began March 13, 1954, and 56 days later, on May 7, shell-shocked survivors of the French garrison hoisted the white flag to signal the end to one of the greatest battles of the 20th century. Photo: AFP.

You had said that one of the public relations triumphs of the 21st century was Obama’s “change we believe in” slogan. You had also said that Obama’s worldwide campaign of assassinations was arguably the most expensive campaign of terrorism since 9/11. Why were you so harsh towards Obama, who has actually won the Nobel Peace Prize? What do you think of Donald Trump and his presidency?

Jubilant mujahideens drive into Kabul in 1980 with posters of the Jamiat-i-Islami commander Ahmad Shah Masood. The huge convoy escorted Sibgatullah Mojadidi from Pakistan to take over power 14 years after the Communist coup that brought about the civil war. Photo: THE HINDU ARCHIVES.

I wasn’t “harsh” towards Obama. It was Obama who was harsh towards much of humanity, contrary to his often absurd media image. Obama was one of the most violent U.S. Presidents. He launched or sustained seven wars and left office with none resolved: a record. In his last year as President, 2016, according to the Council on Foreign Relations, he dropped 26,171 bombs. It’s an interesting statistic; it’s three bombs every hour, 24 hours a day, on mostly civilians. The bombing technique Obama made his own was assassination by drone. Every Tuesday, reported The New York Times, he selected the names of those who would die in a “programme” of extrajudicial murder. All males of military age in Yemen and the frontiers of Pakistan were considered fair game. He increased America’s special forces operations around the world, notably in Africa. Along with France and Britain, he and his Secretary of State Hillary Clinton destroyed Libya as a modern state on the false and familiar pretext that its leader was about to conduct a massacre of “innocents”. This led directly to the growth of the medievalists of ISIS [or Islamic State] and a stampede of immigration from Africa to Europe. He overthrew the democratically elected President of Ukraine and installed an openly fascist-backed regime—as a deliberate provocation to Russia.

The award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Obama was a sham. In 2009, he stood in the centre of Prague and promised to help create a world “free from nuclear weapons”. In truth, he increased America’s nuclear warheads and authorised a long-term nuclear building programme costing a trillion dollars. He prosecuted more whistle-blowers—truth-tellers—than all the U.S. Presidents combined. His singular achievement, one might say, was the demise of the American anti-war movement. Hoodwinked into believing Obama’s messages of “hope” and “peace”, the protesters went home. Obama’s sole distinction was that he was the first black President in the land of slavery. In almost every other aspect, he was simply another American President whose constant utterance was that the U.S. was “the one indispensable nation”, which presumed that other nations were dispensable.

U.S. President Donald Trump. “Many in the U.S. elite loathe Trump not because of his personal behaviour but because of a far more profound embarrassment; he is America without the mask.” Photo: JIM YOUNG/REUTERS.

Perhaps Obama’s cleverness lay in the image that he and others successfully manufactured and cultivated. Donald Trump can also be described as just another (violent) American President. His distinction is that he is a caricature. Many in the U.S. elite loathe Trump not because of his personal behaviour but because of a far more profound embarrassment; he is America without the mask.

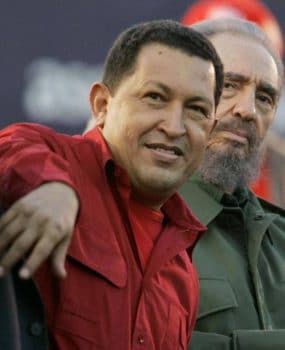

Your film “The War on Democracy” documents the U.S.- orchestrated coup against Hugo Chavez, who stood against imperialism, with the help of the right-wing and capitalist bourgeoisie of Venezuela. This was not a new thing for most of the Latin American countries. But today we see more and more countries of the continent resist U.S. imperialism. Apart from Cuba and Venezuela, left-wing governments are in power in countries such as Bolivia and Ecuador. What is its signal? These days, we are also hearing stories of right-wing offensive in countries such as Venezuela and Brazil. How do you assess the present Latin American political landscape?

I don’t agree that “more and more countries [in Latin America] resist U.S. imperialism”. That may have been true when Hugo Chavez was alive; even then, the U.S. never surrendered its influence on the continent. Today, there is only Bolivia, Nicaragua and, of course, Venezuela, with Venezuela fighting for its life. Most of Latin America is effectively back in Washington’s grip, especially Brazil. Formerly enlightened Ecuador is another prime example. The obsequious government of Lenin Moreno has invited the U.S. military back and threatened to abandon Julian Assange. The economic oppression of the IMF again blights Argentina. Versions of the Washington Consensus, known as neoliberalism, rule almost everywhere on the continent. Cuba is quiet, understandably.

Venezuela’s President Hugo Chavez and Cuban President Fidel Castro in July 2006. “I don’t agree ‘that more and more countries [in Latin America] resist U.S. imperialism’. That may have been true when Hugo Chavez was alive…. Today there is only Bolivia, Nicaragua and, of course, Venezuela, with Venezuela fighting for its life.” Photo: AP.

WikiLeaks has achieved far more than what The New York Times and The Washington Post in their celebrated incarnations did. No newspaper has come close to matching the secrets and lies of power that Assange and Snowden have disclosed. That both men are fugitives is indicative of the retreat of liberal democracies from principles of freedom and justice. Why is WikiLeaks a landmark in journalism? Because its revelations have told us, with 100 per cent accuracy, how and why much of the world is divided and run.

How do you analyse the changing media landscape in the digital era? On the one hand, the Internet has opened up a vast avenue of free space or independent platform. The Internet offers space for counter-narrative, which the mainstream corporate media do not pay heed to. But, on the other hand, you have big digital monopolies that control the digital space. How do you view the situation? What are the challenges ahead?

The challenges are only as great as people allow. Digital data are capitalism’s new gold rush; digital surveillance is democracy’s new adversary. Both differ only in form and scale from the infinite varieties of power that people have had to resist since the beginning of history. Today, we all have a toehold in the digital world; we have the Internet, which is power. How we deploy this power rather than trivialise it depends on our willingness to embrace timeless principles of resistance.

You have been engaged in war reporting for more than five decades. You have covered most of the major wars, including the Vietnam War, the Iraq war and the Afghan war. A number of countries practise increasing armament as an economic policy. The role of huge arms- selling companies is also important. What is the political economy of war?

The political economy of war in the modern era is the political economy of the U.S. The U.S. denies some 80 million of its citizens proper health care while devoting almost 60 per cent of its federal discretionary budget to war preparation. India also has a war economy. In 2018, India joined the world’s top five military spenders, with a military budget of $63.9 billion, which surpasses [that of] France. Almost half the national budget is spent on the military. When I first went to India, I discovered another world existing inside the military bases, inhabited by healthy well-fed people, with clean water and educated children. Outside these and the gorgeous bubbles, India has more malnourished children than anywhere on earth.

Vietnam syndrome

The Vietnam War has been one of the bloodiest and most deadly chapters in the post-War era. You started war reporting in Vietnam. It was the first televised war. Vietnam War is history of the massacre of more than three million people. Could you please speak on the horror you saw in Vietnam? What was the role of the Western media in Vietnam? Recently, you captured the attempt to rewrite Vietnam War history in U.S. textbooks. Even the memory of Vietnam haunts the world’s mightiest state?

Does the “memory of Vietnam haunt the world’s mightiest state”? I am not sure “haunts” is the right word. What annoys America’s apologists is that the army of the “indispensable nation” was expelled from Asia by a peasant nation in Asia: that it suffered a humiliating defeat. They have since sought a “better result” by re-writing what they call “the Vietnam syndrome”, a euphemism for the enduring embarrassment of a catastrophe.

Ken Burns’ 2017 epic documentary series for Public Broadcasting began with the claim: “The war was begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence and Cold War misunderstandings.” The dishonesty of this statement ignores the numerous “false flags” that led to the invasion of Vietnam, such as the Gulf of Tonkin “incident” in 1964. There was no good faith. The faith was rotten and cancerous, and more than four million people died.

I saw something of the suffering: the targeting of civilians described as “cockroaches” by the U.S. commander General William Westmoreland. In the Mekong delta, following a bombing run, there was the smell of napalm, and petrified trees festooned with body parts. I also witnessed heroism. In 1975, I came upon the lone survivor of a Vietnamese anti-aircraft battery, all of them teenage girls; she was kneeling at the new graves of her comrades.

‘Terrorism, product of states’

You have questioned the U.S. war on terrorism as an instance of hypocrisy and double standards. Why do you say so? If that is the case, then the question that arises is, how to curb terrorism? How challenging is the threat of terrorism to a modern and civic life?

The great majority of terrorism is the product of states. Yemen is currently subjected to unrelenting acts of terrorism by the Saudi state, which has sponsored other forms of terrorism, notably the 9/11 attacks. The “war on terror” launched by U.S. President George W. Bush in 2001 was, in reality, a war of terror, resulting in the death of millions of people, mostly Muslims. Powerful states, such as the U.S. and Britain, have developed terrorism as a “strategic” weapon; the support for jehadism in Libya and Syria are vivid examples. The conclusion is or ought to be obvious: when governments stop promoting terrorism, the bloody outrages in their own cities are very likely to cease.

You said that the U.S. has both “good terrorists” and “bad terrorists”. Who are the good and bad terrorists of America?

WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange addressing the media from the balcony of the Ecuadorian embassy in central London on February 5, 2016. Photo: JACK TAYLOR/AFP.

The designation can change without notice. Currently, the Saudis are “good terrorists”; indeed, they are not referred to as terrorists. The ultimate bad terrorists—Al Qaeda—are now good terrorists, fighting on America’s side in its long war against the Shias. The Kurds historically have been both good and bad terrorists; in Iraq, the Kurds were good; in Turkey they were bad. The designation rested on whether or not they are fighting the U.S.’ latest enemy.

By the last decades of the 20th century, the world witnessed the West Asian region becoming the hotspot of Western intervention. After 9/11, this intervention assumed the character of two wars: the Afghan war and the Iraq war. Islamophobia reached new heights in the West. The clash of civilisations theory found champions from the state machinery, the best example being George Bush. How do you historically locate the Western interests in West Asia and also the growth of Islamophobia in the West?

I recommend the work of the British historian Mark Curtis, whose book Secret Affairs traces the close relationship of the British state to extreme Islam. What is clear is that the likes of ISIS and Al Qaeda were the product of Western imperial governments. In Afghanistan, the mujahideen might have remained a tribal influence had it not been for “Operation Cyclone”, a U.S.-led plan to turn extreme Islam into a force that would expel the Soviet Union and bring down the Soviet state. What the West feared in the Middle East [West Asia] was what Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt called “Pan Arabism”. It feared Arab peoples throwing off the shackles of tribalism and feudalism and controlling and deploying their own resources. For this reason, Afghanistan’s only progressive government was declared “communist” and destroyed. For the same reason, Palestinians are held in a state of unending oppression.

Edward Snowden, who worked as a contract employee at the U.S. National Security Agency, in Hong Kong, on June 9, 2013. Photo: AP.

With the U.S.’ recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel on December 9, 2017, the grief and fear of Palestinians has increased. As you have said, they are refugees in their own territory. You have described the aggression on Palestine as the longest military occupation in modern history. Could you elaborate on the Palestinian issue? What are the strategic and geopolitical interests of the U.S. in the region? What is the way forward to bring justice to Palestinians?

A principal U.S. aim is to keep the Middle East uncertain, unstable and divided by tribal war. John Bolton, the U.S. National Security Adviser, has said as much, almost gleefully. This was how the British controlled the region. The design centre of this “policy” is Israel, an imperial anachronism imposed on the Middle East when the world was decolonising. As the Israeli historian Ilan Pappe documents in his latest book, Israel was designed as a prison for its indigenous people, the Palestinians. All Western hypocrisy resides in Israel. [Syrian President] Bashar al-Assad is designated as a monster, but [Israeli Prime Minister] Benjamin Netanyahu, a supreme monster, is granted impunity to control Palestinians, and to a considerable degree, the U.S. Congress and the White House, and the Houses of Parliament in London.

John Pilger, after visiting Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy in London June 22, 2012. Photo: Reuters.

This licence was displayed recently when Jeremy Corbyn, the British Labour leader who may well be the next British Prime Minister, was subjected to an entirely bogus campaign that defamed him as anti-Semitic. Instead of dismissing this contemptuously, Corbyn bowed to it and betrayed his many years of supporting the rights of the Palestinians by agreeing to a definition of Zionism that denied Israel its true status as a racist state. As I write this, Israeli soldiers routinely massacre Palestinians in Gaza, including children. Since March [2018], 77 unarmed Palestinians have required amputation, including 14 children; 12 have been left permanently paralysed after having been shot in the spine. Not a single Israeli has been injured.

What we call globalisation is in the real sense neoliberal capitalism. You exposed probably the first experiment of the structural adjustment programme in Indonesia in the 1960s. You say that there is no difference between the ruthless interventions of international capital in foreign markets these days and those in the olden days, when they were backed up by gunboats. As a journalist familiar with the functioning of the deep state, could you tell us about the evolution of neoliberal economic experiments? How does it work in the present day?

Neoliberalism is an extension of what used to be called monetarism, both of them exotic or extreme versions of the overarching “ism”—capitalism. In the West, led by [British Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher and [U.S. President] Ronald Reagan and their European equivalents, a “two-thirds society” was declared. The top third would be enriched and pay minimal or no tax. The middle third would be “aspirational” with some of them “succeeding” in a ruthlessly competitive world and others falling irrevocably into debt. The bottom third would be abandoned or offered stable impoverishment in return for their obedience. The relationship between people and the state would change from benign to malign. A new buffer class of managers tutored in American corporatism, with its own “culture” and vocabulary, would supervise the conversion of social democracy to a corporate autocracy. Public “debate”, managed by a fully integrated media, would be dominated by “identity politics” with all notions of class banished as an “issue”. False foreign demons (led by Russia, closely followed by China) would be designated “necessary enemies”.

‘European oneness is propaganda’

The experiment of the European Union was eulogised as an indication of oneness of Europeans and a model in the post-socialist era. But Brexit was a big blow to such propaganda. What is your take on the E.U. project? What do you read in Brexit and similar demands?

The European Union is basically a cartel. There is no “free” trade. There are exclusivity rules set down and policed by the central banks, principally the German central bank, with concessionary benefits for the weaker members, namely the movement of labour across borders, though this is now in question. The central aim of the E.U. is the protection and reinforcement of the economic power of the strongest. Brussels is a centralised bureaucracy; democracy is minimal. The “European oneness” you refer to is propaganda, promoted by those who receive most from being in the E.U. The crushing of Greece is a lesson the majority of Britons appear to have understood.

E.U. leaders and their counterparts from the candidate countries pose for a group photo at the conclusion of the E.U. summit in Copenhagen on December 13, 2002. “The European Union is basically a cartel. There is no ‘free’ trade.” Photo: AP.

Your works reflect on re-establish who controls the destiny of humanity, in which way powerful nations, big corporates, bourgeoisie, powerful lobbies make the laws and rules of the world. Democracy seems to be the casualty. In spite of these, we have inspiring stories from around the world of resistance against these mighty forces. Are you optimistic and hopeful about a better world?

There are inspirational forces of resistance in many countries, notably India. Ever since I first reported from India in the 1960s, I have been moved by the will of ordinary people, especially farmers, to stand up for justice in their lives. The recent great march [from September 23 to October 2] of 50,000 farmers from [Haridwar in] Uttar Pradesh to New Delhi was typical. Disciplined, political and resourceful, they have much to teach those of us in the West who imagine protest is mockery of Trump or signing a petition to your Member of Parliament. When the government in Delhi allowed the police to attack the farmers on Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday, they fought back. The political promise of where their movements might lead is perhaps the most vivid revolutionary reminder in the world today. They represent the struggle of people and agriculture everywhere against the neoliberal bulldozers of “urban development”: the theft of human space and its conversion to a grotesquely lucrative commodity. That Indian governments have not responded to the suicides of over 300,000 farmers is an historic tragedy, though one that can be reversed at any time. In one sense, India’s farmers represent us all. As Vandana Shiva has written, their predicament and resistance are a warning that unless we have land security and seed security and agriculture belongs to the people, the colonisation of the world’s countryside by the likes of Monsanto offers as great a threat to human existence as climate change. Of course, people are never still. They will “rise like a lion after slumber…”, as Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote . When the resistance isn’t visible, it is always a “seed beneath the snow”. I have never known as much public awareness as there is today, yet confusion, too. The “populism” of people in the West, so often misrepresented as reactionary, expresses both a will to resist and a disorientation of how to resist. That will change. What never changes is the fear of the powerful for the power of ordinary people.

The kind of journalism that you practise is really a challenging one and indeed tough, too. Through your documentaries, articles and other journalistic works you have questioned the world’s most powerful states and its democratic fraud. What shaped your views to become a dissenting voice in journalism? What are your influences and what keeps your spirit alive?

These days, most of established journalism is an echo of power. It is not the mainstream, an Orwellian word. A true mainstream tolerates dissent, not censors the unpalatable. What shaped my views? Reporting the struggle of societies across the world, including their triumphs, however small, remains an enduring influence. Or perhaps these influences begin early in life. “We support the underdog,” my mother once said to me as a boy. I like that.