Most economists and politicians sing the praises of competition. It is supposed to keep firms on their toes for the benefit of consumers and workers. Well, competition is certainly alive and well in the U.S., but the results are far from positive for working people.

Monopolized product markets

The Open Markets Institute recently issued a report that looks at recent changes in industry concentration in 32 different product markets. It framed its work as follows:

While it may appear as though there are endless brands to choose from online and on the shelf, most are owned by a few large parent companies, the array of labels a mere façade creating the illusion of abundant options.

Locating data on how few companies control individual markets, though, has long been difficult, and not by accident. Although Americans used anti-monopoly policies throughout much of the 20th century to preserve competition, a shift in ideology in the late 1970s allowed increased monopolization across the economy. To shield this pro-corporate turn from the public, the Federal Trade Commission halted the collection and publication of industry concentration data in 1981.

To remedy this gap in public knowledge, Open Markets purchased extensive, up-to-date industry intelligence from IBISWorld, a team of analysts who collect economic and market data, with the intention of releasing the information regarding industry concentration to the public.

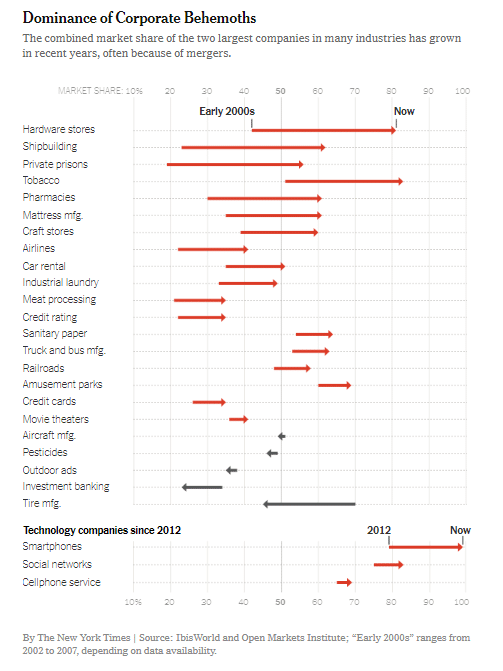

David Leonhardt, in his New York Times commentary on the report, includes the following summary chart:

And as Leonhardt notes, “If anything, the chart here understates consolidation, because it doesn’t yet cover energy, telecommunications and some other areas.”

These trends paint a picture of an economy in which a growing number of industries are dominated by a few powerful corporations, one that belies the conventional view that since our economy is subject to ever stronger competitive pressures, fears of monopoly domination are unjustified. This is not a new insight. For example, John Bellamy Foster, Robert W. McChesney, and R. Jamil Jonna made the same point in a 2011 Monthly Review article:

A striking paradox animates political economy in our times. On the one hand, mainstream economics and much of left economics discuss our era as one of intense and increased competition among businesses, now on a global scale. It is a matter so self-evident as no longer to require empirical verification or scholarly examination. On the other hand, wherever one looks, it seems that nearly every industry is concentrated into fewer and fewer hands.

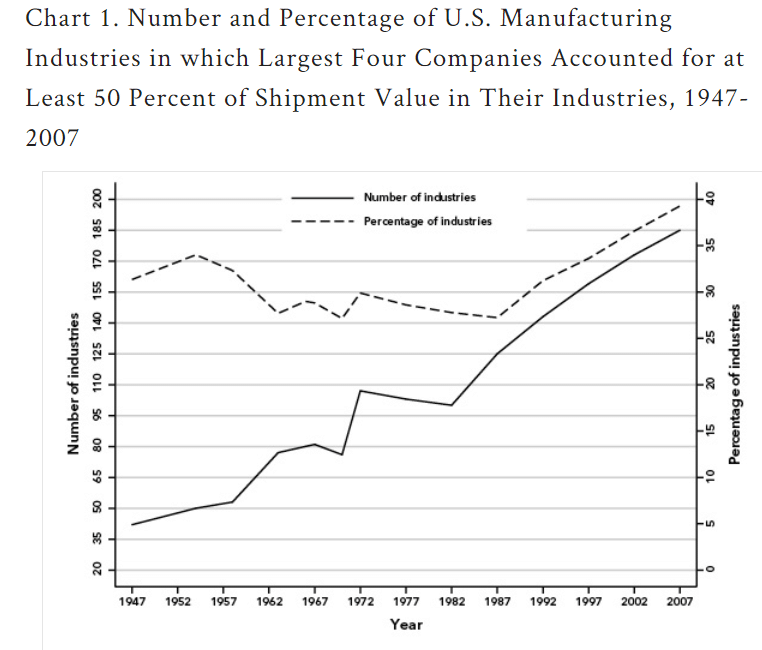

The following chart, taken from the article, illustrates their point about growing industry concentration.

Foster, McChesney, and Jonna explain this “striking paradox” by showing how the competition that captures our attention is increasingly driven by, and largely takes place between, powerful, globally-organized corporations. And, they also discuss the ways in which mainstream economic theory has worked to minimize public awareness of the resulting monopolization of economic processes and its negative consequences for the stability and vibrancy of the economy.

Precarious work

One negative consequence of these competitive battles is worth highlighting here: the transformation of labor relations which is making work, by design, more precarious. As Lauren Weber, in a Wall Street Journal article titled “The End of Employees,” explains:

Never before have big employers tried so hard to hand over chunks of their business to contractors. From Google to Wal-Mart, the strategy prunes costs for firms and job security for millions of workers. . . .

The outsourcing wave that moved apparel-making jobs to China and call-center operations to India is now just as likely to happen inside companies across the U.S. and in almost every industry. . . .

The shift is radically altering what it means to be a company and a worker. More flexibility for companies to shrink the size of their employee base, pay and benefits means less job security for workers. Rising from the mailroom to a corner office is harder now that outsourced jobs are no longer part of the workforce from which star performers are promoted. . . .

Companies, which disclose few details about their outside workers, are rapidly increasing the numbers and types of jobs seen as ripe for contracting. At large firms, 20% to 50% of the total workforce often is outsourced, according to staffing executives. Bank of America Corp., Verizon Communications Inc., Procter & Gamble Co. and FedEx Corp. have thousands of contractors each.

Is it any wonder that income inequality has exploded in the U.S. and even a record-breaking economic expansion in terms of longevity brings few benefits to working people? Clearly, we need some new words, if not an entirely new song, if we are going to keep singing about competition.