Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

It has been almost a year since we got off the ground. Our offices across the world humming with activity. You have received forty-four newsletters from us, eleven dossiers and one notebook and one working document. More is on the way as we enter our second calendar year.

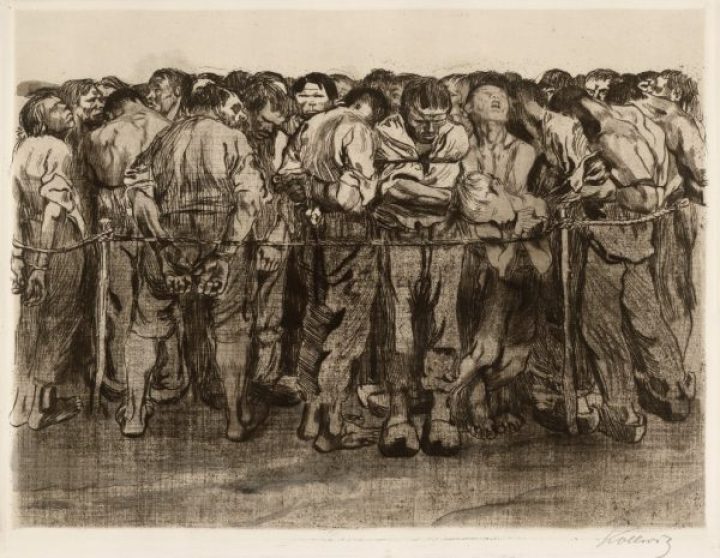

Over the course of these newsletters, we have laid out some of the broad outlines of our concerns and our hopes. We have tried to confront the reality that we live in the Age of the Strongmen–the time of authoritarianism. The broad smiles of the neoliberals have faded. They had their moment to squeeze society and produce prosperity for the few. When the neoliberals squeezed society, wealth travelled upwards to the few and left the many bereft. It was in this condition of unbearable inequality that the Strongmen appeared. They promised jobs and an end to corruption, but what they actually delivered was social toxicity. It was easier to blame minorities for broad social problems than to actually try and solve them. The Strongmen continued the agenda of the neoliberals, but this time without a smile on their faces. They promised violence and they delivered violence. These are ugly times.

In 1935, the German Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote a short note on capitalism and fascism:

Those who are against fascism without being against capitalism are willing to eat the calf, but they are against the sight of blood. They are easily satisfied if the butcher washes his hands before weighing the meat. They are not against the property relations which engender barbarism; they are only against barbarism itself.

‘Property relations’ referred to capitalism–in which a small minority of the world’s population holds the vast mass of social wealth (land, labour and capital). This social wealth is used homeopathically to hire human beings and exploit nature not for any other reason than to make money from money, namely for profit. Concern for humans and nature does not drive the investment of this capital, greedy by its nature.

This capital stands apart from human life, eager to accumulate more and more capital at all costs. What drives the few–the capitalists–is to increase their profits by seeking higher profitability.

In cycles, capitalists find that there are no easy and safe investments that would guarantee profits. This crisis of profitability, as we showed in our first Working Document, leads to two kinds of strikes:

- First, a tax strike, where the capitalists use their political power to reduce the tax burden on themselves and increase their wealth.

- Second, an investment strike, where the capitalists cease investing in the productive sector but instead park their wealth speculatively to preserve it.

These strikes by the capitalists draw social wealth away from social use and dry up the economic prospects of very large numbers of people. With increases in automation and productivity, capitalists begin to substitute machines for workers or else displace workers by the efficiencies of the production process. In this case, investments are made–into machines and into workplace efficiencies–but these have the same impact on society as the investment strike, namely that there are less people employed and more people become permanently unemployed.

High rates of income and wealth inequality alongside dampened aspirations for a better life amongst large sections of the population create a serious crisis of legitimacy for the system. People who work hard but do not see their work rewarded begin to doubt the system, even if they cannot see an exit from the ‘property relations’ that impoverish them. Mainstream politicians who champion the ‘property relations’ and who call upon the desperate to become entrepreneurs are no longer seen as credible.

We hope to provide examples of a possible future that is built to meet people’s aspirations, share glimmers of this future that exist today. Examples of this can be found in our dossiers on housing cooperatives in Solapur (India) built at the initiative of women beedi workers and on the reconstruction of Kerala (India) after the flood. Look out for our work on the excluded workers of CTEP (Argentina) and on the cooperatives of the MST (Brazil).

The Strongmen enter where no such future seems possible. They belittle the mainstream politicians for their failed projects, but then they do not offer a coherent solution to the escalating crises either. Instead, the Strongmen blame the vulnerable for the dampened aspirations of the vast majority. Amongst these vulnerable are social minorities, migrants, refugees, and anyone who is socially powerless. The fangs of the Strongmen are flashed at the weak, who earn the anger of those who have high aspirations but cannot meet these aspirations. The Strongmen draw on the frustrations of people without offering any reasonable exit from a situation of high inequality and economic turbulence.

One theory to explain the problem is that of underconsumption. The general tenor of this theory is that the goods being produced cannot be purchased by the mass of people, since these people do not have enough income to buy them. This is a problem of the demand-side. If there is a way to increase the money given to the mass of the people, then they can increase consumption and save capitalism from its crisis.

One approach toward this underconsumption problem is to increase the delivery of private credit to people who will then be urged–via advertisements–to live beyond their incomes. They will go into debt, but their consumption–it is hoped–will stimulate the economy out of a crisis. Eventually, these people will not be able to pay off their debts. Their debt will balloon and will create serious social problems. Governments will be forced to borrow to lift the burden off the backs of the banks–when the borrowers go bankrupt. The fact of this borrowing pushes the neoliberal governments to create further austerity programmes against social spending. The delivery of private credit to solve the problem of underconsumption typically ends up with social austerity.

A second approach toward this underconsumption problem is for the government to give an economic incentive to consumers through tax cuts or through a direct cash transfer scheme. Either way, the government turns over its money to the people and encourages them to buy goods and stimulate the economy. Once more, it is the government that goes into debt to solve capitalism. Once more, the debt will balloon, and the government will have to go into an austerity programme to appease the creditors and the IMF (when the IMF comes calling, little good results–as Celina della Croce, the Coordinator of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research makes clear in this recent article). Once more social austerity will result, and it will once more dampen the buying power of the public.

The cycle will continue.

Either individuals and families or the state go into debt so as to increase aggregate consumption and save capitalism from itself. By this method, capital itself is not asked to sacrifice anything. It is allowed to pursue the strategy of profitability.

Capital seeks to increase its profitability by various means, such as:

- Substitute machines for people or make people more efficient. This allows firms to hire less people, to take advantage of automation and productivity gains and to leverage their effective competition to wipe out their competitors.

- Transfer factories to areas where wage rates are lower and where regulations of the workplace and of the environment are suppressed.

- Decrease the tax burden by going on a tax strike, transferring their money to tax havens.

- Move capital from productive activities into finance, trade and rent-seeking activities.

- Buy up public assets at low costs and monetarise them for profit.

These strategies allow capitalists to increase their wealth, but at the same time impoverish other people and society.

People are asked to be patriotic. Capital is only asked to be profitable.

For the Left, this situation poses serious challenges. The first set of challenges is to find a way to organise people who find their society shattered and their expectations confounded. The second set of challenges include how to find a policy exit from this system and its limitations.

What are the challenges before us to organise the people against the intractable system?

Aspirations. Over the course of the past five decades, the capitalist media and the advertising industry have created a set of aspirations that have broken the culture of the working-class and the peasantry as well as the traditional cultural worlds of the past. Young people now expect more from life, which is to the good, but these expectations are less social and more individual, with the individual hopes often attached to commodities of one kind or another. To be free is to buy. To buy is to be alive. That is the motto of the capitalist system. But those who cannot afford to buy and who go into debt for their aspirations are also constantly disappointed. It is this disappointment that the Strongmen channel towards hatred. Can left movements channel this disappointment into productive hope?

Atomisation. State cuts of social services, the increased privatisation of social life and the astronomical increase of interaction with the digital world has increased atomisation of human interaction. Where people had previously exchanged ideas and goods, helped each other and inspired each other, now there are less and less venues for such face-to-face interactions. The fragmentation of society and the exhaustion of people to find survival has made it harder for the left to bring people together to create social change. Television and social media now dominate the world of communication. These are venues that are owned by monopoly capitalist firms. The left has always relied upon institutions of society to be its transmitters. As these social linkages fragment, the left dissolves. Can left movements help rebuild these institutions and processes, this society that is our basis?

Outsider. The Strongmen point their fingers at the ‘outsider’–the social minorities, migrants, refugees, and anyone who is socially powerless. It is against these people that the far right is able to build its strength. There can be no left resurgence without a firm and complete defence of the ‘outsider’, a total rejection of the fascistic ideas of hatred and biology that saturate society. It is harder to build a politics of love than a politics of hate. Can left movements develop a politics of love that attracts masses of people?

Confidence. Politics of the people is rooted in confidence. If the people do not feel confident in their activity to either reform or to change the system, then they will not be active. Waves of unrest often lead to increased confidence, but even here the point of emphasis is not the last person to join a protest but the first few people who built the network to build the protest. Social decay leads to a lack of confidence to make political change, particularly when the aspirational society suggests that the only necessary change is for everyone to become entrepreneurial. Can the left produce the sensibility that a future is possible and to engender confidence amongst people to fight to build that future?

Democracy Without Democracy. In societies where there is no democracy, this problem is not immediate. In such places, the immediate task is to win the fullest democracy. In those societies where democracy is the main form, or where there is at least an illusion of democracy, the oligarchy and imperialism have used many methods to undermine democracy, to dominate society without suspending democracy. The methods used are sophisticated, including to delegitimise the institutions of the state, to disparage elections, to use money to corrupt the electoral process, to use social media and advertising to destroy opposition candidates and to utilise the least democratic institutions in a democracy–such as an unelected judiciary–to erode the power of elected officials. Can the left defend the idea of democracy from this attrition without allowing democracy to come to mean merely elections and the electoral system?

Our research institute–Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research–is conducting investigations along these five lines.

Once you have organised people to push for a new world system, what is the policy framework that needs to be adopted? It is here that intellectuals must put their heart and soul into action. We need to think hard about the many creative ways to use our social wealth to solve the immediate problems of humanity–hunger, sickness, climate catastrophe. We need to find ways to uproot the basis of wars. We need to use our creativity to reconstruct the productive sector around forms such as cooperatives. We need to use social wealth to enrich ourselves culturally, making more physical places for us to interact, to produce culture and art. We need to use our social wealth to produce societies that do not force people to work to survive but that subordinate work to human ingenuity and passion.

It is cruel to think of these hopes as naïve. It tells us a lot that it is easier to imagine the end of the earth than to imagine the end of capitalism, to imagine the polar ice cap flooding us into extinction than to imagine a world where our productive capacity enriches all of us.

Our entire staff joins me in wishing you a happy new year.

Warmly, Vijay.

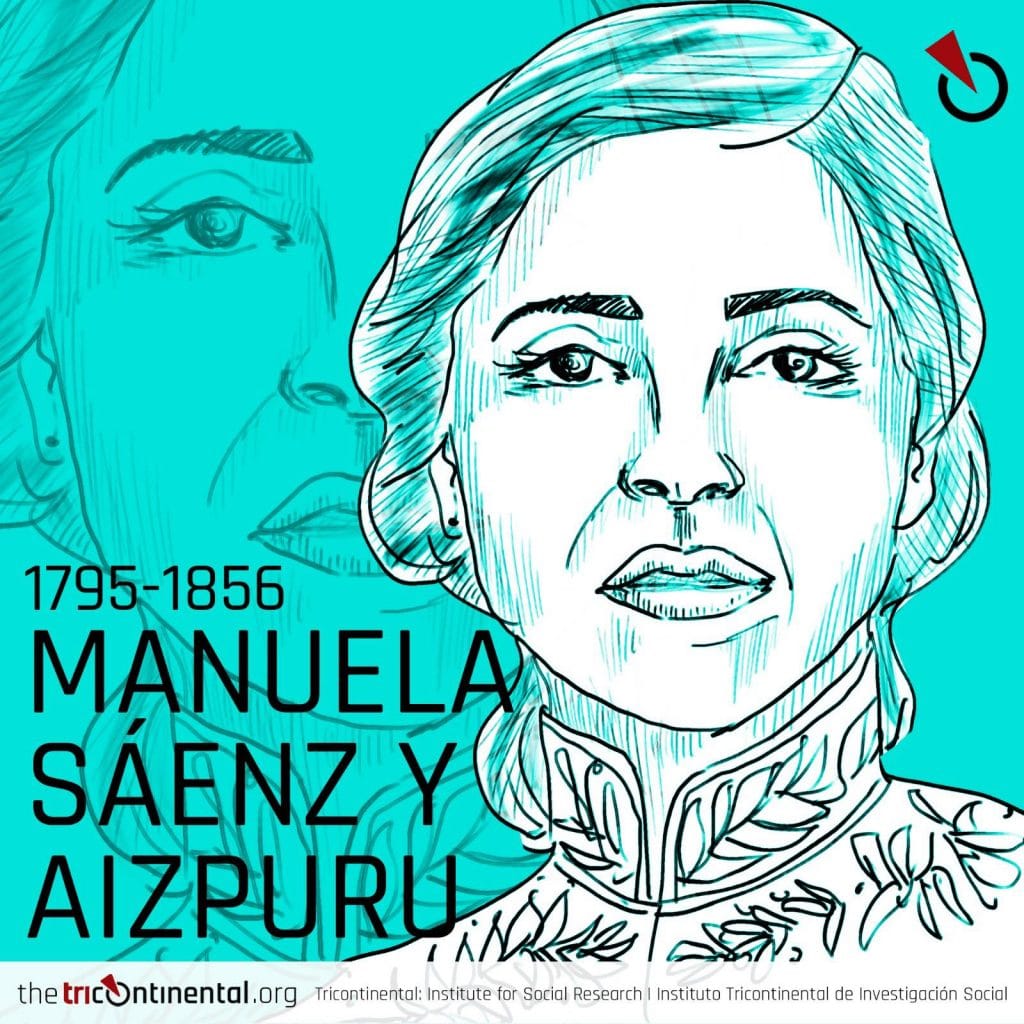

PS: (see below) we celebrate the birth of Manuela Sáenz y Aizpuru (1795-1856), the revolutionary who was born in Quito (Ecuador) and who would fight for Latin America’s independence alongside Simón Bolivar. After she saved his life, she was known as the Liberator of the Liberator.