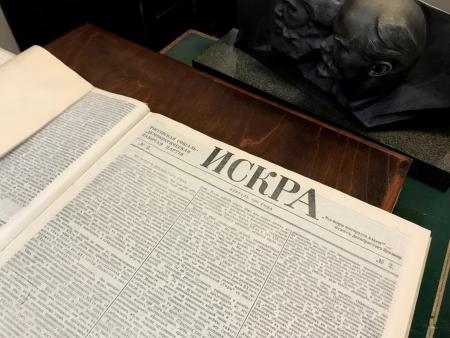

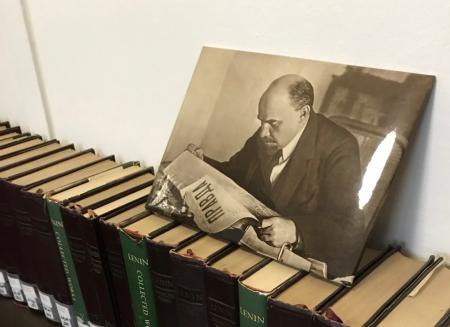

I’m in the musty basement of the Marx Memorial and Library in London. I find Marianna, buried amongst piles of posters—she is the volunteer responsible for digitizing its vast archive of posters. I am taken to a small office where Lenin spent two years, while in exile, writing for Iskra (“spark”), the underground Bolshevik newspaper and ideological heart of the Party.

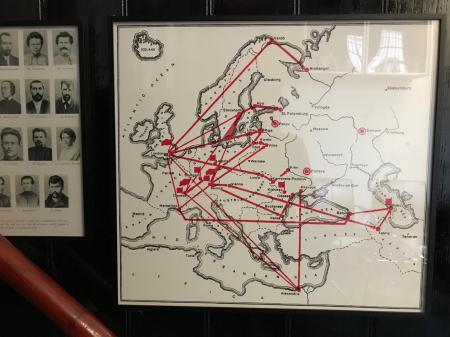

On Iskra, Lenin had said, “A newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, it is also a collective organizer. Political agitation is impossible without a regular and widely distributed newspaper. Its contributions and distributors formed the nucleus of the future Party.” There is a framed map on the wall with red arrows detailing the distribution of the paper throughout Russia and Europe—a reminder of the many lives that were risked so that the publication could find its readers.

I look at the tome on the small desk. It collects the old Iskra issues. I am visually repelled by the tightly packed Cryllic text. The frugality of space reads like a testament to the extremely difficult material and political conditions under which the publication was produced. As if the feat of reading it is as great as it is of producing it. I challenge any serious activist of today’s Instagram age to sit through an issue Iskra.

But I did not come here for comrade Lenin. I came to look through the archive’s collection of posters and publications produced by the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL).

I have a few piles of Tricontinental Magazines and Bulletins in front of me. I have never held an original copy before. These objects speak to a passage of time, in its specific historical conditions. I chronologically re-order all of them. The earliest two-colour publications were printed on rice-paper-thin paper that meant text bled onto the reverse pages. The later publications had full colour covers on high quality paper, perfect bound. I study every cover, flip through the pages.

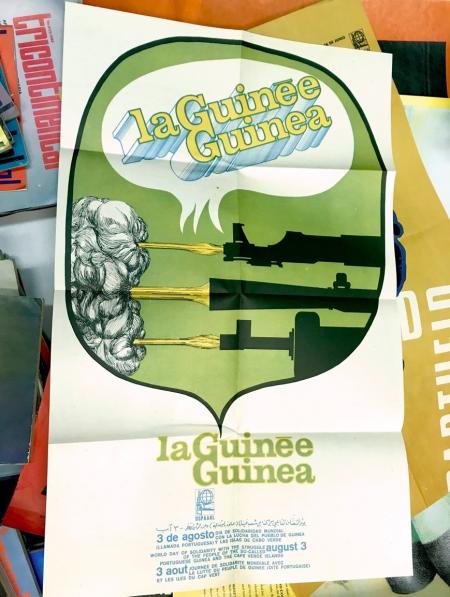

I come across a folded piece of paper wedged inside one of the issues. I open it up—it’s a poster announcing the “World Day of Solidarity with the Struggle of the People of the So-Called Portuguese Guinea and the Cape Verde Islands”. I thought for a moment about the two Portuguese colonies that form part of my own story—Macau, the homeland of my mother, and Brazil, the place I now call home. I run to Marianna with the poster, to share this simple joy of discovering the poster as it was designed to be discovered. We had to make the difficult decision of keeping the poster in its original issue or to join the poster archive. The latter choice was its fate.

There is a Tricontinental special digest dedicated to Che Guevara. It is undated but I suspect it must be around the time of his CIA-backed murder in the forests of Bolivia. It is a homage to el comandante through the many posters that OSPAAAL and Casa de las Americas made of him. The styles are as diverse as Che’s disguises. It is printed in full colour. One poster per page with ample margins. I think about the generosity of space in the layout—space for reflection and breath. I admire the quality of paper and luxury of ink used, then think about the embargo. This printed artefact, through the labour and materials behind its production, is in itself an anti-imperialist assertion.

To raise and complicate consciousness—the highest aim of the revolution itself.—Susan Sontag

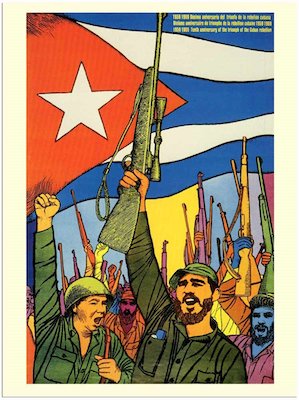

I am working on a Facebook banner image for the new organization we are about to launch—Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, a global south and movement-driven research space inspired by the legacy of the Tricontinental Conference and spearheaded by Vijay Prashad. I’ve been studying René Mederos’ poster he made for the tenth anniversary of the Cuban Revolution—a group of soldiers fronted by Fidel holding their rifles in the air with the Cuban flag flying in the backdrop. I think about what the rifle of today would be in the battle of ideas. I collage together a new sketch, replacing rifles with pens, paintbrushes, and books. I replace the soldiers with women, mothers, and children.

Since our launch in March of this year, we have produced 11 dossiers ranging from themes of shackdweller movement in South Africa to crisis on the Korean peninsula to a massive workers’ housing cooperative in India. We have launched 44 weekly newsletters highlighting the most pressing news about peoples’ movements around the world. We have published a political notebook and working document for those looking for deeper study, and dozens of weekly hand-drawn portraits, uplifting the stories revolutionaries around the world, particularly women.

As a self-taught graphic artist, trained through social movement work over the past decade, I am inspired by the internationalist orientation of OSPAAAL designers, by their deep engagement with movements and struggles, by the seriousness of their work.

On the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution, we may not need armed struggle in most of our contexts, but we surely need a lot more than pens, paintbrushes, and books to wage war against global capitalism, rising fascism, and climate collapse. Like the madmen of yesteryear, we need all the knowledge, skills, and tools so we can turn them against capital itself.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research understands that the ideological battle must be fought not only with words but also with the production of images and visuals that propel the work of movements forward. We invite self-taught and professional artists and designers, particularly those involved in movements, to join the Network of Artists and Designers.

I hope you join us.

Tings Chak is the Lead Designer for Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. www.thetricontinental.org

Instagram: @thetricontinental