The Great Recession of 2008 marked the end of a lengthy period of international economic growth and rapidly increasing international trade. Now, some ten years later, economic activity, including trade and foreign direct investment, remains far below pre-crisis levels with little sign of revival. In fact, with growth falling in Europe and Japan, and many third world countries struggling to deal with ever larger trade deficits and worsening currency instability, the weak recovery is likely on its last legs.

Some analysts now question whether the transnational corporate created globalization system, which the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) calls hyperglobalization, is in the process of unwinding. While real tensions, compounded by U.S.-initiated trade conflicts, do exist, UNCTAD’s 2018 Trade and Development Report provides evidence showing that the system still serves the interests of the core country transnational corporations that established it and they continue to strengthen their hold over it.

Global trends: slowing growth and international trade

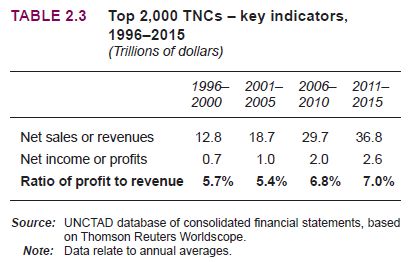

As panel A in the figure below shows, the years 1986 to 2008 were marked by strong global growth and export activity, with so-called “developing countries” accounting for a significant share of both, thanks to the spread of Asian-centered, cross-border production networks under the direction of core country transnational corporations. It also shows the decline in global growth and tremendous contraction in trade in the post-crisis period, 2008 to 2016.

It is this contraction in global trade, along with the decline in foreign direct investment, that has fueled discussion about the future of the current system of globalization, and whether it is unwinding. However, trends in the export elasticity of economic output, illustrated in Panel B, are an important indicator that the system is evolving, not fraying, and in ways that benefit core country transnational corporations.

The export elasticity is a way of measuring the effect of exports on national economic activity; the greater the elasticity the more responsive national production is to exports. What we see in Panel B is that the export elasticity of developed countries rose in the post-crisis period, while that of developing countries continued its downward trend. This trend highlights the fact that core country transnational corporations continue to craft new ways to capture an ever-greater share of the value created by their production networks, and more often than not, at the expense of working people in both developed and developing countries.

Transnational corporate gains

Exports are dominated by large companies, overwhelmingly transnational corporations. As the authors of the Trade and Development Report explain:

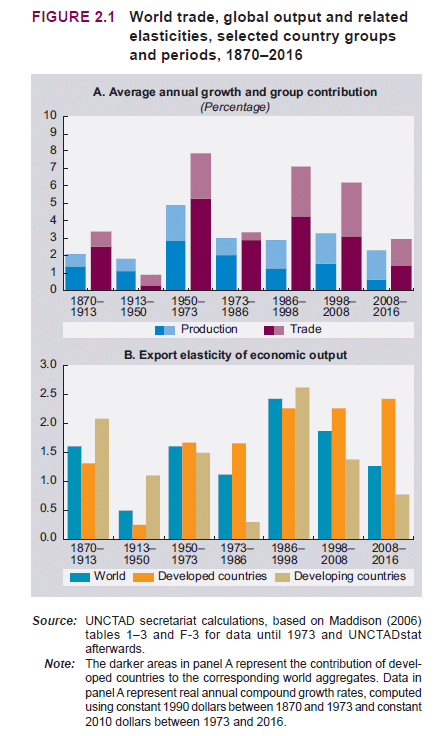

recent evidence from aggregated firm-level data on goods exports (excluding the oil sector, as well as services) shows that, within the very restricted circle of exporting firms, the top 1 per cent accounted for 57 per cent of country exports on average in 2014. Moreover, while the share of the top 5 per cent exceeded 80 per cent of country export revenues on average, the top 25 per cent accounted for virtually all country exports.

Moreover, as we can see in the figure below, the share of exports controlled by the top 1 percent of developed country and of G20 firms has actually grown in the post-crisis period.

Studies cited by the Trade and Development Report found that concentration is even greater than the above figures suggest. One found that “the 5 largest exporting firms account, on average, for 30 per cent of a country’s total exports.” Another concluded that “in 2012, the 10 largest exporting firms in each country accounted, on average, for 42 per cent of a country’s total exports.”

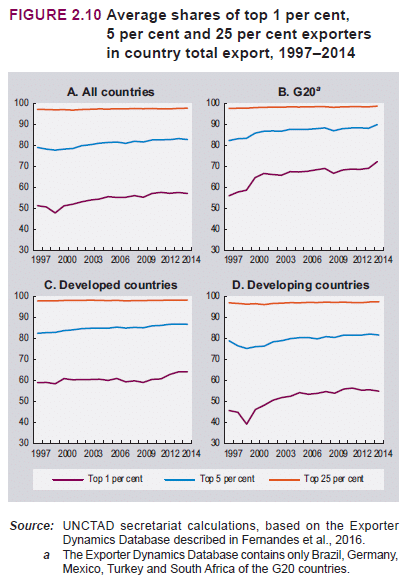

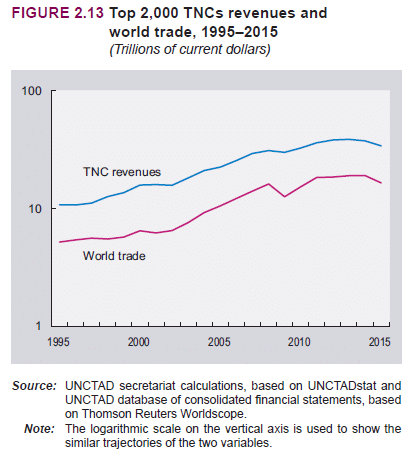

The next figure looks at earnings for a group composed of the 2000 largest transnational corporations, a group that includes firms from all sectors. Not surprisingly, their earnings closely track global trade and have recently declined in line with the downturn in world trade. However, as the table that follows makes clear, that is not true as far as their rate of profit is concerned. It has actually been higher in the post-crisis period.

In other words, despite a slowdown in world trade, the top transnational corporations have found ways to boost what matters most to them, their rate of profit. Thus, it should come as no surprise that transnational capital remains invested in the global system of accumulation it helped shape.

Transnational capital strengthens its hold over the system

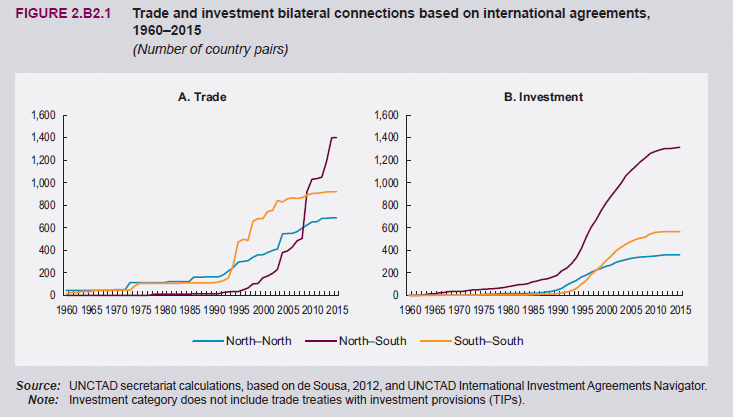

A powerful indicator of transnational capital’s continuing support for the existing system is the steady increase, as highlighted in the figure below, in new trade and investment agreements between countries of the so-called “north” and “south.” These agreements anchor the existing system of globalization and, while negotiated by governments, they obviously reflect corporate interests.

In fact, these new agreements have played an important role in boosting the profitability of transnational corporate operations. That is because they increasingly include new policy areas that include “increased legal protection of intellectual property and the broadening scope for intangible intra-firm trade.” This development has allowed core country transnational corporations to secure greater protection and thus payment for use of intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, rights to design, corporate logos, and copyrights from the subcontracted or licensed firms that produce for them in the third world. These new agreements have also made it easier for them to shift their earnings from higher-tax to lower-tax jurisdictions since the geographical location of services from most intangible assets “can be determined by firms almost at will.”

According to the authors of the Trade and Development Report,

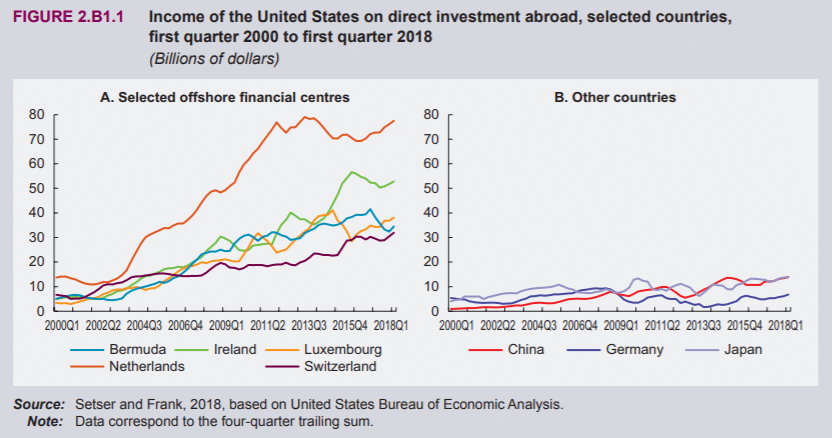

Returns to knowledge-intensive intangible assets proxied by charges for the use of foreign [intellectual property rights] IPR rose almost unabated throughout the [global financial crisis] and its aftermath, even as returns to tangible assets declined. At the global level, charges (i.e. payments) for the use of foreign IPR rose from less than $50 billion in 1995 to $367 billion in 2015. . . . a growing share of these charges represent payments and receipts between affiliates of the same group, often merely intended to shift profit to low-tax jurisdictions. Recent leaks from fiscal authorities, banks, audit and consulting or legal firms’ records, revealing corporate tax-avoidance scandals involving large TNCs, have made clear why major offshore financial centers (such as Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Singapore or Switzerland) that account for a tiny fraction of global production, have become major players in terms of the use of foreign IPR.

The growing use of this tax avoidance strategy by U.S. transnational corporations, as captured in the figure below, highlights its strategic value to transnational capital.

Social costs continue to grow

The globalization process launched in the late 1980s transformed and knitted together national economies in ways that generated growth but also serious global trade and income imbalances that eventually led to the 2008 Great Recession. The weak post-crisis recovery in global economic activity is a result of the fact that without the massive debt-based consumption by the U.S. that helped temporarily paper over past imbalances, the globalized system is unable to overcome its structural tensions and contradictions.

However, as we have seen, transnational capital has still found ways to boost its profitability. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, their success has only intensified competitive pressures on working people, raising the costs they must pay to maintain the system. An UNCTAD press release for the Trade and Development Report emphasizes this point:

Empirical research in the report suggests that the surge in the profitability of top transnational corporations, together with their growing concentration, has acted as a major force pushing down the global income share of labor, thus exacerbating income inequality.

It is of course impossible to predict the future. A new crisis might explode unexpectedly, disrupting existing patterns of global production. Or workers in one or more countries might force a national restructuring, triggering broader changes in the global economy.

What does seem clear is that current economic problems have not led to the unwinding of what UNCTAD calls hyperglobalization. In fact, the Trade and Development Report finds that “many advanced countries have since 2008 abandoned domestic sources of growth for external ones.” The current system of globalization was structured to benefit transnational capital, and they continue to profit from its operation. Unless something dramatic happens, we can expect that they will continue to use their extensive powers to maintain it.