Nick Estes did not intend to write a book about Standing Rock. He was working on his dissertation about Indigenous rights at the United Nations when the movement against the Dakota Access pipeline exploded on the edge of one of the 16 northern Plains Indian reservations of the Oceti Sakowin people, known by the U.S. government as the Sioux. Estes, a member of the Lower Brule Sioux tribe who grew up in South Dakota, felt he had little choice but to change his plans. He traveled home to the Dakotas and wrote much his book sitting on his aunt’s couch, drawing on oral histories shared by elders and relatives and cross-referencing them with archival documents.

Cover of Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance by Nick Estes. Courtesy of Verso Books.

The result is “Our History Is the Future,” which traces Indigenous resistance from the Lakota people’s attempt to deny Lewis and Clark passage down the Missouri River in 1804, to the Red Power movement’s demands for treaty enforcement in the 1960s, to today’s Indigenous-led fights against fossil fuel projects. Writing about the massacre at Wounded Knee, where 300 Indigenous men, women, and children were murdered by U.S. soldiers in 1890, Estes highlights the revolutionary premise of the nonviolent Ghost Dance movement the victims followed. With a long tradition of daring attempts at decolonization, Estes argues, Indigenous people represent a powerful challenge to the profit-driven forces that threaten continued life on the planet.

In addition to working as an associate professor of American studies at the University of New Mexico (and an occasional Intercept contributor), Estes is an activist with the Albuquerque-based Red Nation, which organizes around a range of issues, including fracking near sacred sites and Diné communities in New Mexico’s Greater Chaco region, child detention on the border, and urban police violence against Native people. Estes spoke to The Intercept about Native activism after Standing Rock, the Green New Deal, and the rebirth of Indigenous culture that the mainstream media is missing. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you explain what you mean by the title phrase of your book, “our history is the future”?

I look at the Ghost Dance prophecy, which was an anticolonial uprising among particularly Lakota and Dakota people on the northern Plains in the late 19th century, but also a widespread spiritual movement that went up the west coast of Canada and down to parts of what is today Mexico. If they were completely harmless, then the United States wouldn’t have deployed its army against starving, horseless people at Wounded Knee. The reason it represented such a threat was not because Lakota and Dakota Ghost Dancers were going around and murdering white settlers—it was because it was a vision of the future.

When you subjugate a people, you not only take their land and their language, their identity, and their sense of self—you also take away any notion of a future. The reason I chose this name is because in this particular era of neoliberal capitalism, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. The argument I’m making is that within our own traditions of Indigenous resistance, we have always been a future-oriented people, whether it was taking up arms against the United States government, whether it was taking ceremonies underground into clandestine spaces, whether it was learning the enemy’s language. This pushes back against the dominant narrative that Indigenous people are a dying, diminishing race desperately holding on to the last vestiges of their culture or their land base. If that were the case, then I don’t think we would have an uprising such as Standing Rock or, today, Line 3 or Bayou Bridge, or the immense amount of mobilization around murdered and missing Indigenous women.

You write about the idea of accumulation of resistance, which “is not always spectacular, nor instantaneous, but that nevertheless makes the endgame of elimination an impossibility.” What does that mean for Indigenous-led movements today?

Growing up as a Lakota person, your heroes are Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull; they’re also [American Indian Movement activists] Russell Means, Madonna Thunder Hawk, also Phyllis Young. We don’t necessarily choose those circles of resistance. We’re born into it, because we are still colonized people. The tradition of resistance within the Oceti Sakowin dates back to the first arrival of Americans. We weren’t stupid people—we knew what they were about, and we came to know the United States, after Lewis and Clark trespassed through our territory in 1804, as a predator nation. Those people who first met Lewis and Clark told their children, and their children told their children.

To be Indigenous is to be political by default, because we’re not supposed to be here, first of all, and second of all, we’re Indigenous because of the land we sit atop, and the land we protect, and the territories we protect, and that means that we will always be in the way of development. There’s no neutral stance that Indigenous people can take.

I love somebody like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the fact that she herself is a water protector and her campaign began at Standing Rock. I also recognize the limitations of her position in Congress. Obama couldn’t stop the pipeline; none of the people he appointed in his administration could stop the pipeline. We have to recognize that Indigenous movements in places like the northern Plains can do things we cannot expect politicians to do—things that only Indigenous movements like NoDAPL can do. It’s false to assume that power lies somewhere else.

A protester is treated after being pepper-sprayed by private security contractors on land being graded for the Dakota Access pipeline near Cannon Ball, N.D., on Sept. 3, 2016. Photo: Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images.

The Intercept’s coverage of NoDAPL focused on the collaboration between police and private interests and the criminalization of Indigenous resistance. How does Standing Rock fit into the more quotidian role of police in Indigenous people’s lives?

In the past, Indian people in certain communities could not leave the reservation without a pass. They could not leave without permission from an Indian agent. To leave the open-air prison was to be an outlaw, and you were subject to being captured or hanged or imprisoned. Even though that may not be true today, culturally and socially it’s still a practiced norm. In Albuquerque and places like Rapid City, South Dakota, one of the common refrains that police say when they’re enacting violence on Indigenous people is “Go back to the reservation.” Indigenous people are seen as not belonging even on their own homelands.

I would say that the everyday forms of violence are much more deadly than the police violence that happened at Standing Rock, even though it was brutal, and it caused a lot of trauma. [Police] intensified the things they had already mastered. They already knew how to profile Indigenous people — they’re border-town cops. This is Morton County, just north of the Standing Rock Indian reservation. For a while, they had Red Tomahawk, the guy who killed Sitting Bull, on their State Highway Patrol patches. They embrace that history; they’re not confused about the role that they’re playing. They’re just the modern iteration of the 7th Cavalry.

In your book, you describe a disaster that the Oceti Sakowin people faced that perhaps holds some valuable lessons for organizers confronting the climate crisis. Could you explain the Pick-Sloan Plan and the flooding of Indigenous land?

I think about this strong push toward the Green New Deal—and I agree in principle and in spirit with the Green New Deal—but I also kind of cringe a bit. The Pick-Sloan Plan at the time was one of the largest dam projects in history. In 1933, the federal government began to construct a massive dam near the Fort Peck Indian Reservation of the Assiniboine and Sioux people (the Nakota people). It was a public works project during the Great Depression designed to provide relief and employment to white workers in Montana and the surrounding region. As a result, hundreds of Native people were displaced, and thousands of acres of their lands were flooded to essentially save the settler economy from itself. This has been a historical phenomenon in the United States: Whenever there’s a crisis of legitimacy for the status quo for the capitalist system, it’s oftentimes Indigenous lands that are sacrificed.

The inspiration for the Green New Deal really began in the camps at Standing Rock, where Ocasio-Cortez started her campaign. But we have to remember the pitfalls of fixing settler economies at the expense of Indigenous lands. Sometimes I feel that the burden of transition is placed on Indigenous people. I see that with these transition plans—now the Navajo nation is going to be producing solar power to fuel the entire Southwest. OK, so has it really changed from a resource colony? Because the Navajo nation was producing coal that powered the whole Southwest, and now it’s producing oil to power the global economy in the United States.

I think it’s useful to look at the dams, which were applauded by everyone in the United States. John F. Kennedy came and gave a speech, and my grandmother was actually in the audience. My grandmother talked until the day she died about what it was like to shake hands with John F. Kennedy, but, at the same time, he was there to celebrate the destruction of our homeland. So there’s always this trade-off. That means we have to address the primary contradiction, which is settler colonialism, if we’re going to honestly and justly transition out of the current carbon economy.

You close the book with a demand for the emancipation of the earth from capitalism. We’re at a crisis point ecologically, and a lot of people are looking to the Green New Deal as a central point of organizing. What do you think is required for something like this to be a meaningful vehicle for justice?

The interesting thing about the way the Green New Deal has been framed is that it’s a “pragmatic” environmental policy. There are elements that are missing from the Green New Deal that should be fought for. The deal omits a clear commitment to keeping fossil fuels in the ground, and it needs to reject carbon-pricing schemes that simply privatize the air we breathe and allow the industry to keep extracting, transporting, and burning fossil fuels so long as it has a “green face.” Those are things that Indigenous communities have been fighting for, and I don’t know why they’re not in there.

The other thing, going back to that pragmatic language—pragmatic for whom? We have 10 years. What is pragmatic about extending the behemoth of fossil fuel capitalism? It’s either us or them, and there’s nothing pragmatic about sustaining the system, because the system is destroying us. It’s an issue of race and class in the sense that the most vulnerable are always going to be the poor brown people of the earth, the humble of the earth, and we recognize that.

This shouldn’t be a capitulation to power to sell it to the Nancy Pelosis of the world, who unabashedly is calling herself a capitalist. She’s not interested in undoing these systems. So it’s something we should fight for, but it’s also something we should recognize as limited and flawed in some ways, and we should demand more and really redefine the parameters of what a “pragmatic” response to global climate change is.

Demonstrators gather to protest the Dakota Access pipeline in front of the White House in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 13, 2016. Photo: Jim Watson (AFP: Getty Images).

You’ve talked before about the lack of Indigenous authorship in mainstream media. In the wake of Idle No More, Native authors became more a part of Canadian media, but that hasn’t happened in the U.S. to the same degree in the wake of NoDAPL. Do you see that changing?

Increased representation of Indigenous people in media and the popular imaginary in Canada occurred because of the Idle No More movement and the federal government’s Truth and Reconciliation process, which actually required certain reforms at universities or in media rooms to open up spaces for Indigenous people. But this isn’t Canada; this is the United States.

Not only do we suffer a lack of representation in the news media, but we also suffer a lack of representation in writing and telling our own stories. That doesn’t mean that non-Indigenous people can’t write and tell our stories with integrity and credibility, but there’s unwillingness to really engage that disparity. I do think there are strides being made in certain newsrooms across the country, but there isn’t a national effort to change that. And this is happening in a media landscape where things are changing rapidly. There’s a precarity in journalism where a lot of people are freelancing and driving down the costs of stories. I’ve heard all of these things from Native journalists themselves. And some of them, journalists that I really respected, couldn’t find a place in a major newsroom, so they ended up just leaving the profession altogether.

I think right now, Indian Country is in kind of a rebirth of culture, of media and art and political activism—but the irony of it is you wouldn’t know by opening up the New York Times. We’re only a news story when it’s a white woman claiming she has Native American DNA, or when a bunch of white Catholic school boys taunt a Native elder at the Lincoln Memorial. I used to be a little bit cynical about this, but I’m actually much happier now, because I do see those changes happening even if they’re not being noticed by the mainstream.

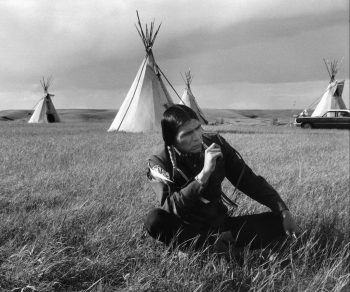

Dennis Banks, co-founder of the American Indian Movement, at the time of the treaties conference in 1974. Photo: Michelle Vignes (Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images).

Tell me about the Red Nation and your organizing work in New Mexico.

We formed the Red Nation back in 2014 after the killing of Kee Thompson and Allison Gorman, also known as Cowboy and Rabbit. They were two Navajo men who were brutally murdered by three young men on the west side of Albuquerque. It was at the tail end of this upsurge in protests against police violence in Albuquerque, but one thing I noticed was there wasn’t a lot of concern around police violence against Native people. There were some elements of the movement that were focusing on it, but by and large, it was erased. I remember [AIM co-founder] Dennis Banks came to one of our Red Nation events, and we were talking about border-town violence, and he was like, “The American Indian Movement was founded first and foremost to end police brutality. That was 50 years ago, and we’re still doing it today.”

We are an Indigenous feminist organization. This generation of young Native people are doing things that weren’t hip or cool in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, during the Red Power movement. They’re addressing things such as heteropatriarchy and the use of tradition in their own communities as a tool of oppression. A lot of our young people are nonbinary, they’re gender nonconforming, they’re queer. They’re two-spirit [an umbrella term for Indigenous peoples who do not subscribe to Western gender binaries and heteronormative sexuality]. That element of our societies was one of the first things to be almost annihilated and extinguished, because it represented an alternative political order. There’s a reason why these generals and politicians chose our men to sign treaties and negotiate. They used our men as a tool of conquest. So we’ve inherited that in our own communities. It relates to the work that we do with our unsheltered relatives on the street, who are cast out of their communities for being trans or queer.

We have comrades and relatives around the world, so we try to be in alliance with those movements as well. We have groups studying what’s happening in Venezuela right now with the U.S.-backed coup, and we have people working on Guatemala. We’re not really doing anything new in that regard. We’re building upon the work of the Red Power movement and the American Indian Movement and, as I detail in my book, its close relations with the Palestine Liberation Organization. There’s a reason why there were Palestinian flags flying at Standing Rock.

How do you see the resistance at Standing Rock being carried forward?

Before Standing Rock happened, we were not as prepared as we are now to confront the long-term struggle. It’s not just about stopping Keystone XL, which is slated to begin construction in the United States this June. Tribes are ready; organizations are ready. They know we’re ready — they’ve already been collecting intelligence on us. But this isn’t just about defeating pipelines. There’s been so much talk about envisioning what we want for our communities. Now that this fire is lit, and it can’t be put out, what are we going to do with it? After Standing Rock, all of Indian Country became friends on Facebook—that’s been a common joke. So we’ve been unified in a certain way that’s really important.

What we stand for is the continued existence of Indigenous life on this earth—but also the continued existence of life on this earth. The longer-term goal is to continue to develop as a nation of the Oceti Sakowin, with other Indigenous nations, on this path that we were meant to be on—to imagine what it would be like had we not been colonized, to imagine a future in which not just Indigenous people fit, but all people fit. All those elements existed for a brief moment in time at the camps at Standing Rock.