This article is featured in Red Pepper Issue 223: Feminist Futures. Subscribe now for the best in news, views and cutting-edge analysis. —Red Pepper Eds.

When you hear of French feminism, it tends to be strongly associated with images of writers such as Simone de Beauvoir and Hélène Cixous, and crowds of women demonstrating throughout history, from the French revolution to May ’68. The Declaration of the Rights of Women in the late 18th century shines as an early example of the mass struggle of women in France to avoid being silenced behind the universalist illusion of their male counterparts. Even the republican slogan of ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ lays down a framework, if only in theory, for a broader movement towards freedom for all.

Yet alongside this glorious past and the broad political possibilities it opens up (illustrated nowhere as effectively as in the successful slave revolution in Haiti), it is much rarer for the description of French feminism and its political legacy to include an exploration of the imperialist and racist practices that have characterised it for some, in particular those from France’s former colonies. France’s treatment of indigenous Algerian women throughout the 132 years of colonialism provides an insight into some of the failings that have shaped political discourse in France in relation to women’s liberation.

Not feminism but feminisms

Naturally, there are many different forms of feminist thought and practice in France – and we shouldn’t associate the oppressive practices and failings of the French state, or the individuals and groups who serve as an extension of it, with those of feminism more widely. That said, if we are to make sense of contemporary French politics and the continuous assault on Muslim women’s bodies, right to choose and freedom of religion, one has to look closely to the underbelly of the republic’s offer to ‘liberate’ Muslim women and women of colour.

The claim of women’s liberation became a defining feature of France’s mission civilisatrice (civilising mission), through which it justified its presence in the global South and its aggressive imposition of ‘French values’ on its subjugated colonial population. This mission—not dissimilar to Rudyard Kipling’s ‘white man’s burden’—served as a way to justify the extraction of natural resources, the theft of land and the super-exploitation of indigenous labour. It imposed a French schooling system, entirely in the French language, which taught the French state’s official history, culture, and values in a bid to bring the colonised out of darkness and into the light. The most absurd of its methods have become sadly famous, such as the way populations from Mali to Vietnam were forced to learn about ‘their ancestors: the Gauls’.

While there is much to say about the danger of teaching populations one is trying to subdue that they too are children of the revolutionary republican tradition, it is equally important to focus on how rhetorical liberation can become a powerful weapon of repression. And so it was for the women of Algeria. French women, teachers and state officials were recruited in campaigns to liberate Algerian women from the supposed shackles of tradition, religion and Algerian patriarchy—a process that has since been summarized by Gayatri Spivak, albeit in a different context, as ‘saving brown women from brown men’. Algerian women became the battleground where the French state attempted to stamp its authority.

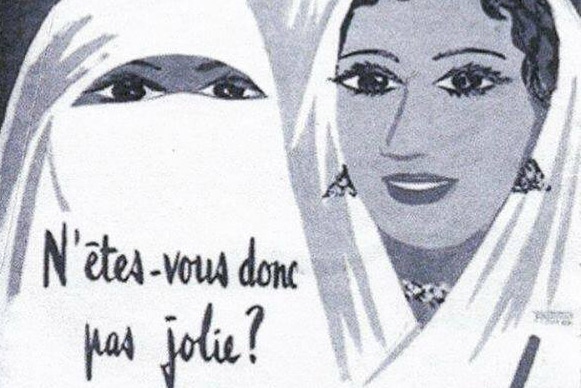

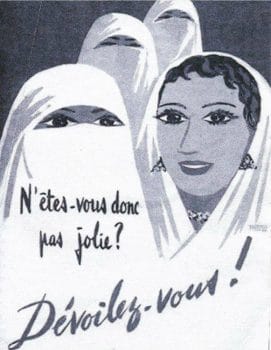

‘N’ëtes-vous donne pas jolie? Dévoilez-vous’ (‘Are you not pretty? Reveal yourself!’): A colonial poster from French-ruled Algeria.

The campaign to ‘liberate’ Algerian women centred around unveiling them. Posters appeared in the streets that depicted an Algerian woman wearing the traditional white haik, next to an unveiled woman with make-up. The posters read: ‘Unveil yourself! Aren’t you pretty?’ Algerian women were also called upon to participate in public ceremonies of unveiling where their haiks were burnt on the public square, while French women were found assaulting haik-wearing women in the street in an attempt to forcefully ‘free’ them.

Ironically, Algerian women mobilised these stereotypes against the colonial powers. While haik-wearing women were considered submissive and lacking political agency, and unveiled women in western clothes were imagined as liberated representatives of the French state behind enemy lines as it were, both became actively involved in smuggling documents, weapons and information for the FLN (National Liberation Front), Algeria’s anti-colonial movement.

This process is captured beautifully in the film The Battle of Algiers, as well as in Frantz Fanon’s Algeria Unveiled. Fanon documents how ‘the unveiled Algerian woman […] assumed an increasingly important place in revolutionary action’—turning the coloniser’s need to ‘unveil’ them into a way of going unseen amid colonial society.

Confrontations and contradictions

These confrontations have more than a historic importance. They shed light on the contemporary place of Muslim women in France and the double aggression against them, both by the state and by a section of the feminist movement.

When, in 2005, two teenage Muslim girls of Jewish heritage who had converted to Islam were excluded from their school for wearing the hijab—a process initiated by their teacher as well as their headteacher, who were both members of radical socialist organisations—a national debate emerged on the place of visibly Muslim women in French society. This triggered a series of events that led to the banning of the hijab in French state-funded institutions, while the burka—worn by around 300 women in the whole of France—was made illegal. A more recent example of this process led to the exclusion of Muslim women from university for wearing skirts that the institution judged to be ‘too long’ and hence Islamic. This whole process was actively supported by the French left and its feminist organs.

This full-frontal assault by the state and the so-called progressive institutions in France was carried out under the banner of liberating Muslim women from patriarchal control. It did not matter that these women protested their right to choose their dress and religious practices. It did not matter that the ban effectively pushed many Muslim women out of the public sphere. Nor did it matter that they now had to choose between access to higher education under the humiliating glare of the republic or respecting their religious convictions.

Many socialists and feminists, activists and concerned citizens, both Muslim and not, stood up against this assault. When hijab-wearing Muslim women were attacked by other women during the annual demonstrations that mark International Women’s Day in France, broad alliances of feminists across France organised a collective response under the banner of ‘An 8 March for All’.

Just as a brave minority stood with the people of Algeria against French colonialism, a courageous and important minority stands today against state racism and discrimination. The lesson remains the same: the promise of 1789—liberty, equality and fraternity—depends always on solidarity from below against state violence from above. In the famous words of the Algerian revolutionary slogan: only one hero—the people.