President Trump has long pointed to the U.S. balance of payments deficit as a sign of U.S. economic weakness. Of course, his nation-state focus, and claim that trade deficits with countries such as China and Mexico are the result of unfair trading practices that benefit foreign business and workers at the expense of U.S. business and workers, is misleading. These deficits owe much to the operation of U.S. corporate controlled cross-border production networks, which have boosted U.S. corporate power and profits largely at the expense of workers in all three countries.

Criticizing past administrations for selling out America, President Trump has pursued a series of policies—renegotiated trade agreements, tariff wars, public shaming of corporate disinvestment, and tax reform—all of which are supposed to help rebuild the U.S. economy by encouraging U.S. firms to modernize and expand their U.S. operations. These policies have all failed to achieve their stated aim. In fact, they have, largely by design, only served to strengthen existing corporate dominated patterns of international production and value capture.

As a result, there has been little change in U.S. trade patterns. The U.S. trade deficit in goods, as shown below, has continued to grow every year of the Trump presidency.

Strengthening TNC power and profits

After first threatening to dissolve NAFTA, President Trump eventually pursued a rewrite of the NAFTA agreement. However, his proposed changes to the agreement primarily speak to corporate needs, especially the new chapters that increase protection for intellectual property rights and promote greater cross-border freedom for electronic commerce and digital trade. Similarly, the Trump tariff “war” against China appears primarily aimed at forcing the Chinese government to tighten regulations protecting U.S. intellectual property rights and open new sectors of its economy to U.S. foreign investment, especially the finance sector.

President Trump has also engaged in occasional twitter “wars” against corporate decisions to close or relocate abroad part of their operations. Initially, corporate leaders felt pressure to modify or delay their decisions. Now, no doubt reassured by the general policy direction of the Trump administration, they no longer appear worried about his periodic outbursts. For example, both GM and Harley Davidson recently announced plans to shut domestic plants in favor of overseas production and have largely ignored Trump’s tweets critical of their globalization activities.

Much has been written about these efforts, but little about the consequences of the last policy, tax cuts, on U.S. TNC decision-making. The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” Act, signed into law on Dec. 22, 2017, was promoted as a way to encourage U.S. transnational corporations to bring back funds held outside the country and boost their domestic investment. However, as a Bank of France blog post by Cristina Jude and Francesco Pappadà makes clear, this initiative, like the others, has done nothing to change U.S. corporate behavior, although the lower tax rates make it more profitable.

Jude and Pappadà focus on profit hording and profit shifting. Profit hording refers to the accumulation of “non-repatriated earnings” by U.S. TNCs. Economists estimated that U.S. firms held approximately $2.5 trillion outside the country at the end of 2017 and the Trump administration predicted that a large share would be brought back thanks to the one-time lower tax rate included in the 2017 act. Apple alone is said to hold $252 billion in offshore accounts.

Although economists speak of corporate earnings held abroad, in fact most of those earnings are held in the US. However, as long as those funds are not used for certain purposes, such as paying dividends to shareholders, financing domestic acquisitions, guaranteeing loans, or making investments in physical capital in the US, they can be invested in the U.S. tax free.

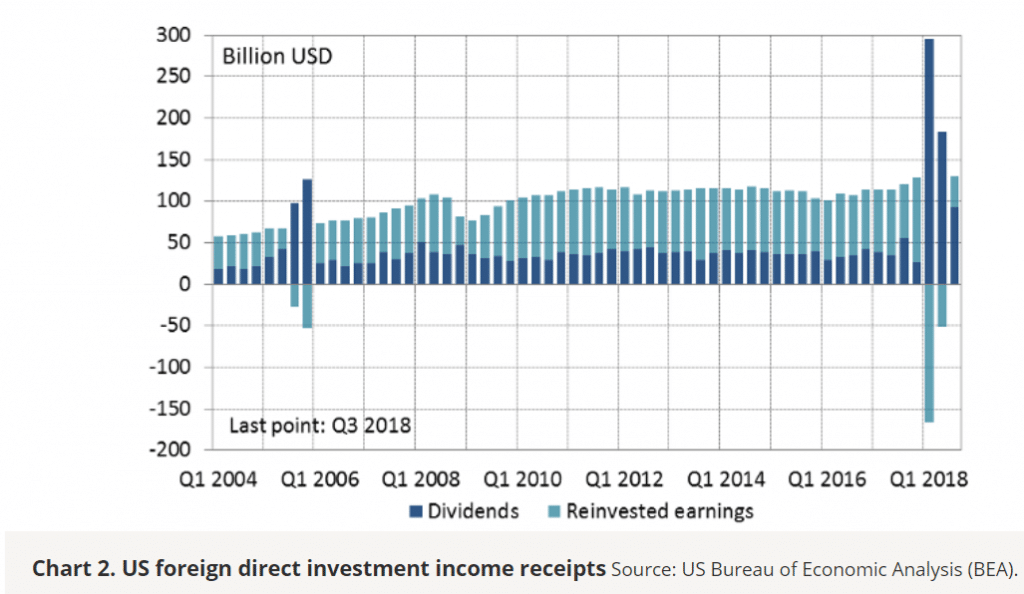

As we can see in the chart below, U.S. companies did respond to the one-time lower tax rate by “repatriating” some funds. Dividend payouts went up, which resulted in a period of negative “reinvested earnings” in foreign affiliates.

However, as Jude and Pappadà explain:

Despite the permanent cut of the standard corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, the adjustment of repatriated dividends and reinvested earnings appears limited to the first and second quarters of 2018. Indeed, dividends decrease substantially in quarter three, whereas reinvested earnings return to positive as they were before the tax reform.

The response of U.S. companies to the corporate tax reform mainly consisted in the partial repatriation of previously accumulated stocks of earnings (around 20 percent of the total) due to the temporary lower tax. This firms’ behavior is similar to the one observed in 2005 when another law granted U.S. multinationals a one-year tax holiday to repatriate foreign profits at a 5.25 percent tax rate.

Thus, the tax change produced a one-time shift in a relatively small share of the non-repatriated earnings held by leading U.S. TNCs, with stock owners the primary beneficiaries. Moreover, this shift did not change the overall size of income receipts from U.S. foreign direct investment, as the increase in dividends was offset by the negative reinvested earnings.

If the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” is to have a long-lasting effect on the U.S. trade balance, it needs to stop the corporate practice of tax shifting, which is how TNCs generated the huge sum of money held as non-repatriated earnings. Profit shifting refers to the corporate strategy of using various means such as transfer pricing, often achieved using intellectual property rights over patents and trademarks, to book profits generated from U.S. activities in a lower-tax jurisdiction. As Jude and Pappadà point out, “six small jurisdictions (Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland), which count for less than 1 percent of the world’s population, hold 63 percent of the overall profits earned abroad by U.S. multinationals.”

Google is, as Tim Hyde explains, one of the firms that makes good use of this strategy:

it is able to claim billions of profits in Bermuda each year (corporate tax rate: 0 percent) even though it has no office building there and not even any employees on the island…. this is legitimate because the rights to Google’s search and advertising technologies are technically owned by a subsidiary called Google Holdings housed in Bermuda, thanks in part to a trick called the Double Irish Dutch Sandwich. Other Google subsidiaries pay billions in royalties to the Bermudian company Google Holdings for the rights to use its technology, which was originally invented by Google employees in California and sold to Google Holdings in 2001. Those billions of profits are reclassified as Bermudian rather than American or Irish and thus not taxed.

If U.S. firms booked their earnings in the US, rather than in a foreign tax haven, foreign direct investment receipts would decline, net U.S. service exports would increase, and the overall trade deficit would narrow.

An Oxfam study of profit shifting by leading pharmaceutical companies shows just how important this strategy is to U.S. TNCs and how much we lose from it:

Abbott, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, and Pfizer—systematically stash their profits in overseas tax havens. As a result, these four corporate giants appear to deprive the United States of $2.3 billion annually and deny other advanced economies of $1.4 billion. And they appear to deprive the cash-strapped governments of developing countries of an estimated $112 million every year—money that could be spent on vaccines, midwives, or rural clinics.

Pharma corporations’ “profit-shifting” may take the form of “domiciling” a patent or rights to its brand not where the drug was actually developed or where the firm is headquartered, but in a tax haven, where a company’s presence may be as little as a mailbox. That tax haven subsidiary then charges hefty licensing fees to subsidiaries in other countries. The fees are a tax-deductible expense in the jurisdictions where taxes are standard, while the fee income accrues to the subsidiary in the tax haven, where it is taxed lightly or not at all. Loans from tax-haven subsidiaries and fees for their “services” are other common strategies to avoid taxes….

Further opportunities for avoiding taxes involve locating corporate brand or patents in tax havens, and fees for marketing, finance, or management services. For example, a pharmaceutical corporation may bill much of its R&D costs on products consumed around the globe to a subsidiary in a tax haven where R&D rights are registered, even though not a single researcher is based there. That immediately creates a cost in the country where the product is consumed, which minimizes the tax bill, and an artificial profit in the tax havens, where almost no taxes are paid in return.

As a result of this practice:

Pfizer posted losses on U.S. operations of 8 percent in 2013, 25 percent in 2014, and 31 percent in 2015. The pattern has continued, with Pfizer posting losses of 32 percent in 2016 and 26 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, Pfizer’s international operations earned 56–58 percent in 2013–2015 and even more in the two years since (64 and 72 percent). The story is similar though less extreme for Abbott and Johnson & Johnson.

The pharmaceutical industry is no outlier. According to a study by three economists, Thomas Tørsløv, Ludvig Wier, and Gabriel Zucman, “close to 40 percent of multinational profits were artificially shifted to tax havens in 2015.”

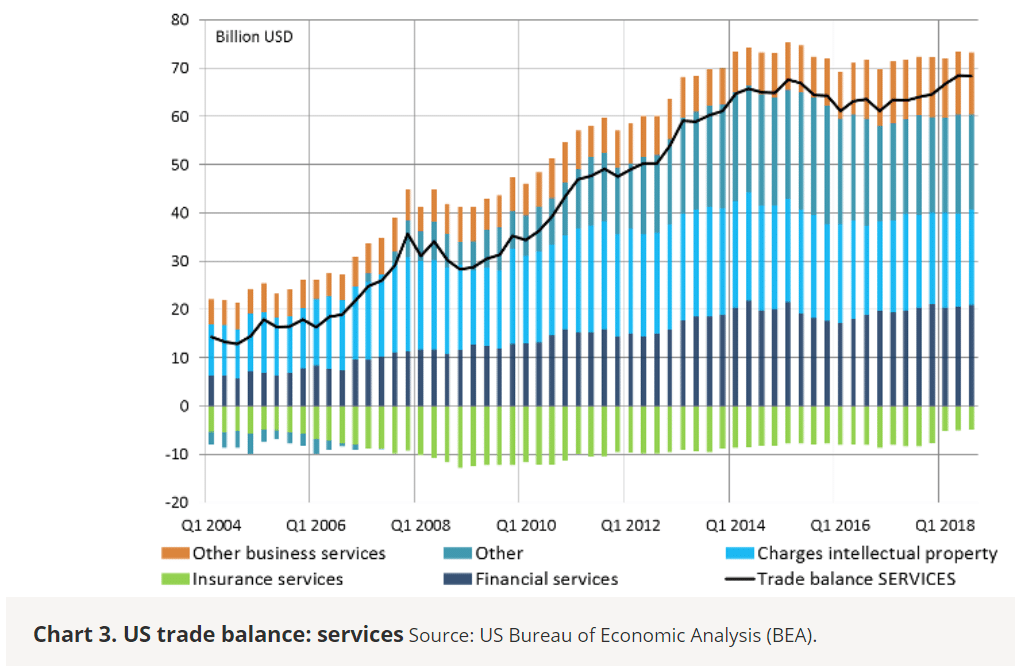

And, as the chart below reveals, there is no sign that passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has produced any change in U.S. TNC profit-shifting activities. As Jude and Pappadà discuss:

In Chart 2, we observe a change in the composition of foreign direct investment income, but the balance remains stable at its pre-reform level. Moreover, this is not associated with an increase in net exports of services. In particular, the decomposition of the services trade balance in Chart 3 shows that there has not been any increase in intellectual property charges, for which profit shifting is more relevant. At the moment, it is too soon to assess the full impact of the reform as U.S. multinationals may take time to adjust the location of their assets and activities. However, the profit shifting decisions of multinational firms do not seem to be affected so far.

In sum, for all of Trump’s bluster, his administration has done nothing to produce a change in TNC business practices or improve the health of the U.S. economy. In fact, quite the opposite is true, as almost his initiatives have been designed, above all, to expand the reach and profitability of leading U.S. corporations.

Note: The original title of this article was “The Trump Administration: Lots of Noise But Nothing Changed For US TNCs.” —Eds.