In Open Veins of Latin America (1971) Eduardo Galeano wrote, ‘our wealth has always generated our poverty by nourishing the prosperity of others’. Galeano’s book lyrically details Latin America’s long history, from its colonisation to the era of military coups of the 1970s. In this long period, the wealth of the continent was stolen to benefit imperial powers elsewhere (in Europe and in North America) as well as local oligarchs. The people and land were leached of their wealth. Forests, rivers, soil and subsoil—all were converted from their natural state into raw material for capitalist accumulation. The more the resources, the more the pillage and the poorer the people.

In the midst of the continent is the vast Amazon, the world’s largest tropical rainforest. The Amazon is the main bio-genetic reserve for the planet and in it sits enormous mineral resources. If you destroy the Amazon, you destroy the planet. To plunder the Amazon is the road to planetary destruction.

The Amazon has long been the epicentre of disputes over the desires of the large powers to give their capitalist firms an advantage in exploration and extraction. The largest part of the rainforest is inside Brazil, which has been pressured to allow foreign firms to ravage its riches. Brazil has responded to these external interests with initiatives—such as tax exemptions, public loans, donation of lands and public investments in infrastructure—that facilitate the exploration of the territory.

Destruction of the Amazon—done by Brazilians and non-Brazilians alike—has been ongoing with deforestation, aggradation of rivers, expropriation of land and slaughter of indigenous people. This threat to the Amazon has only become more severe since Brazil’s ‘soft coup’ in 2016 and the subsequent right-ward trend.

Dossier no. 14 has been researched and written by the Brazilian office of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. The team in São Paulo benefited greatly from the inputs by Professor Edna Castro (Federal University of Pará), an expert in neo-extractivism, and by Luiz Zarref (MST National Coordination), who holds a doctorate in geography from the Federal University of Goiás and was crucial in shaping our understanding of the role of agri-business in the Amazon for this dossier. We are also grateful for the new book—Amazonia: Riqueza, Degradaçao e Saque—by Professor Gilberto Marques (Federal University of Pará).

The Immensity of the Amazon Region

The Amazon is the largest tropical rainforest on the planet. It represents 61% of Brazil’s landmass and contains 77% of all of Brazil’s conserved land. It holds one-fifth of the world’s fresh water. The rich forests and soils of the Amazon store a substantial amount of carbon that would otherwise leak into the atmosphere and contribute to catastrophic climate instability. The Amazon is legendary for its bio-diversity.

Brazil’s part of the Amazon is home to 170 different indigenous communities. 98% of all indigenous land in Brazil is inside the Amazon Rainforest region. There are many communities that have lived in the region for more than 11,000 years. In the Amazon, there are 357 remaining quilombola communities (which take up 32% of Brazil’s landmass). When Africans escaped from the institution of slavery (which ran from 1532 to 1888), they formed quilombos, many of which remain active till today. There are ribeirinhos—people who live near rivers and make their lives around the rivers—as well as people who make their living through tapping rubber, cultivating chestnut, babaçu and coconut trees. The Amazon is a region that has been home to people for more than 11,000 years.

The Amazon is not merely Brazilian. It is shared with Colombia, Peru and Venezuela—these, with Brazil, are amongst the five most biodiverse countries in the world. Bolivia, Ecuador, Guyana and Suriname also find their territories in the Amazon. The biodiversity of the region is at the core of South American integration.

The destruction of the Amazon has serious consequences not only for Brazil, but for all of Latin America—and the world. The instruments of this devastation are several: deforestation, logging and illegal burning of the forest, the disorderly expansion of livestock, roads and soybean cultivation as well as the implementation of large mineral and energy projects.

From the series “Ilha do Combú”, Municipality of Belém, Pará (one of the municipality’s 42 Islands), 2014. Credit: Evna Moura.

The International Context

The crisis of capitalism triggered in the United States in 2007 had a global impact. It can be compared to the crisis of 1870 and the crisis of 1929, crises that forced capitalism to reinvent itself.

The current crisis comes at a time of great international churning, with the geopolitical tussles over hegemony between the United States of America and its allies, the Chinese and the—now substantially weakened—BRICS bloc. The outcome of this crisis was the strengthening of financial capital and the imposition of an unfavourable correlation of forces for the working class and the world’s poor. Historically conquered rights have been eroded as the shields of unions and of laws have been eaten into. Not only have oppressions on lines of gender and race increased, but the offensive to exploit biodiversity has intensified.

Capitalism’s response to the crisis has been to restore the shine on neo-liberalism and to encourage the predatory accumulation pattern that centralises public wealth into the hands of the few, a process described by the Marxist geographer David Harvey as ‘accumulation by dispossession’. Powerful mining firms have launched an offensive against natural assets in places such as Brazil. If they are able to corner the market on these assets, they can improve their own profitability and deflect the impact of the ongoing crisis of capitalism. The tendency is to turn Latin America, once more, into a supplier of raw materials rather than to allow the continent to diversify its economic activity. Latin America, through this process, will become increasingly dependent on agribusiness and on mining.

Certain key strategic dimensions open up as a result of this offensive on the economies of Latin America:

- Push to control raw materials, including oil. This has a direct impact on the profitability of firms that now are able to earn enormous returns on capital investment.

- Increase in the concentration of wealth and land by smaller and smaller sections of society.

- Reform of the State to adjust to the new demands of capital accumulation.

- Push to use the State’s resources to underwrite the work of private business. This has a direct impact on the distribution of State revenue towards the public good.

- Push to undermine historically won rights that enhance the power of the working-class. This has a direct impact on the distribution of income.

- Increased disorientation in society that leads to an escalation of drug trafficking and illegal economic activity and to an increase in violence and social intolerance, particularly racism.

- Increase in the ideological hegemony of the right, including the neo-liberal intelligentsia.

Xavante (Mato Grosso). Photo from the XVIII Meeting of Traditional Cultures in Chapada dos Veadeiros, 2018. Credit: Evna Moura.

The National Context

The current Brazilian context is shaped by uncertainty—including uncertainty of labour and social rights. But what is certain is that the entire political process from before the 2018 elections had been driven to a large extent by the fight over the Amazon. The national and international elites attached to the agribusiness and mining sectors had a pioneer role in the soft coup process made up of the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, the persecution of President Lula, and the recent election of President Jair Bolsonaro in October 2018.

The agribusiness lobby in the National Congress became the great supporter of the administration of Michel Temer (2016-2018). In exchange, this lobby was able to get—among other things—the government to withhold this sector’s debts. Temer’s illegitimacy, however, prevented the agribusiness sector from winning many of its demands.

When Jair Bolsonaro ran for the presidency in 2018, he spoke openly on behalf of agribusiness and mining, including his intention to roll back regulations and open the Amazon to business interests. He said he would hand over indigenous lands, quilombola territories and conserved land to agribusiness and landowners for exploration and exploitation. They revelled in his commitment to eradicate the landless movements and to abolish environmental regulations (including over the overuse of pesticides). He said he would give priority to the infrastructural projects and the financing needs of these business sectors.

Bolsonaro united the interests of various fractions of Brazil’s national bourgeoisie with the interests of international capital (notably, with the imperialist bloc, with the emerging neo-fascist bloc and with financial capital). Their goals are clear:

- Defeat the Brazilian working-class and deploy brutal forms of labour exploitation.

- Plunder the commonly-held goods of the people, such as oil, gold, water and land, as well as to curtail Brazil’s biodiversity. The State would facilitate the rentier dynamics of the national bourgeoise and provide the platform for transnational capital to accumulate at will.

- Appropriate the social wealth held in public funds, in state-owned companies and in the public sector (health and education). There is a direct policy to privatise public wealth and subordinate these institutions to transnational finance capital.

- Realign Brazil’s foreign policy orientation, from one of being pledged to multi-polarity to one that is subordinate to the interests of the United States of America.

Bolsonaro’s presidency has engineered many shifts related to environmental issues, some cleverly disguised and others patently obvious. Bolsonaro wanted to abolish the Ministry of the Environment, but that would have been very provocative. Instead, he restructured the ministry to gut it of its enforcement ability. Many of the functions of the Ministry have been eliminated, others suspended and yet other reassigned to other ministries. The point is to render such ministries ineffective. That is what the government has been doing. The head of the Ministry of the Environment is Ricardo Salles, the founder of a movement to ‘straighten Brazil’ (Movimento Endireita Brasil). In Salles’ view, to ‘straighten Brazil’ means to liberate business interests from regulations on labour and environment exploitation. Since 2017, Salles has faced a civil action for the violation of environmental laws to damage the Tietê River protected area.

Amazon and the Projects of Predatory Exploitation

The exploitation of the Amazon follows clearly the pattern of what is known as neo-extractivism. This is a concept that describes the removal of large volumes of natural resources from a country before they are processed into more refined materials or goods. The raw materials are destined for export, with little advantage to the country that produced them. This technological gap—where the wealth of natural resources is drained from countries like Brazil in the tricontinent to the Global North—is a continuation of a long history in which the wealth of Latin America’s ‘has always generated our poverty by nourishing the prosperity of others’, as Galeano would say. The country that holds the wealth is forced to forfeit it to its former coloniser who holds a near-monopoly over the technological capacity to produce and refine these resources. Having been forced to forfeit this part of the production process, the former colonies are left with no choice but to purchase the final products at much higher costs. The country of raw materials is left dependent on the world market. It can do nothing else but sell its raw materials and then use that money to import goods at much higher prices.

Earlier exploitation in the Amazon was for rubber, which was tapped to satisfy the ravenous hunger of the industrial revolution. The Brazilian state provided a platform for transnational firms to take advantage of the resources. Large numbers of people from Brazil’s Northeast were displaced into the Amazon to become the labour force for the exploitation of the rubber trees. When U.S. control over rubber plantations in Asia satisfied world demand, the Amazon’s trees and workers were forgotten. Brazil did not control the market and was utterly subordinate to the transnational firms.

After the 1964 civil-military coup, the dictatorship occupied the whole territory of the Amazon in the name of the defence of national sovereignty. The real goal, however, was to contain the workers and to seize the land so as to set in motion a new environment for the exploitation of the Amazon. It was seen as the ‘frontier of natural resources’, which were delivered to transnational corporations once more. These conglomerates have increased their power over the years. To better understand their work, we have divided this section into three areas:

- Mining

- Agribusiness and the exploration of biodiversity

- The natural world (including the construction of dams and the theft of native knowledge of Amazonian plants).

From the series “Ilha do Combú”, Municipality of Belém, Pará (one of the municipality’s 42 Islands), 2014. Credit: Evna Moura.

Mining

Mining in the Amazon dates back to the discovery of manganese (essential to iron and steel production) in the state of Amapá in 1945 by the mining firm Icomi. Icomi represented the interests of the U.S. transnational corporation Bethlehem Steel. Three years before this discovery, the Brazilian state had already created a company to facilitate mining: Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (CVRD). The company studied the Amazon in search of minerals to exploit. CVRD created Amza (Amazônia Mineração S/A)—a joint partnership of CVRD and U.S. Steel. Such partnerships allowed the state to guarantee the extraction and production of raw materials by private firms. U.S. Steel would not take risks. It would be protected by Amza. Similar manoeuvres allowed Mineração Rio do Norte, a subsidiary of the Canadian firm Alcan, to extract bauxite without risk.

Not until 1967, in the midst of the military dictatorship, was the Amazon seen as a major export region for minerals on an industrial scale. This took place with the sale of the Brazilian company Jari Ltd. to Universe Tankship, a subsidiary of the U.S. conglomerate Daniel Ludwig. They began to mine for bauxite and kaolin. These conglomerates were given tax concessions by the Brazilian government.

The Brazilian state took the responsibility to build all the necessary infrastructure for mining—such as highways and hydroelectric plants. The power generated was entirely for the mining firms and not for the people who lived in the Amazon, nor for the workers who were taken there. Little wonder that the indigenous people, the remaining inhabitants of the quilombos, the landless people, and the small producers remain in constant conflict with the state’s project to exploit the Amazon.

By the 1990s, the role of the CVRD had changed dramatically. In 1997, the CVRD was sold into private hands for U.S. $3.3 billion. It was a fire-sale. The company had valued assets—such as 12.9 million tons of iron—which were not factored into the sale price. Public assets were given into private hands. In 2003, the firm ceased to be a Brazilian company. The New York Stock Exchange traded 67% of its shares, while 33% remained in Brazilian hands.

The privatization of CVRD came as private, transnational conglomerates took over the mining of the Amazon. The Brazilian state now acts merely as the facilitator of private extraction. The largest mining companies operating in Brazil today are Vale (Brazil), HydroNorte (Brazil), CBMM (Brazil), Magnesita (US), Anglo American (UK), Albras (Brazil, Japan), Alcoa (US), Maracás Mine (Canada), Kinross (Brazil and Canada), Hydro Paragominas (Norway and Australia) and MRN (Brazil).

From the series “Ilha do Combú”, Municipality of Belém, Pará (one of the municipality’s 42 Islands), 2014. Credit: Evna Moura.

Of the many minerals extracted from the Amazon, iron accounts for 44.5% (copper follows at 11.1%). China and Japan are the major consumers of Brazilian iron. Much of this iron comes from the mines of Carajás (in the state of Pará). Brazil’s economy, reliant upon high commodity prices, fluctuates according to the demand for iron from China and Japan. Any slowdown there hurts Brazil.

Brazil mainly exports primary raw materials in the crudest state, without any necessary technological innovation to add value to the commodity. In 2017, 78.3% of Brazilian exports from the Amazon region were unprocessed, with 7.7% semi-manufactured (such as alumina and primary aluminium) and with 14% exported as manufactured goods.

Vale alone accounted for 62% of all exports from the Amazon (70.2% from the state of Pará). It has not upgraded its mechanisms for mining. Outdated infrastructure, as well as impunity granted by the State, are among the main reasons that Vale and Samarco are responsible for the biggest social and environmental crimes in Brazil. These disasters include the collapse of tailing dams in Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019)—both in the state of Minas Gerais and both owned by Vale. These tailing dams are used to hold waste products from the mining of iron ore. These disasters revealed the number of such tailing mines across the Amazon as well as the number of hydroelectric plants that are now in operation, under construction or being planned. As each mountain of ore is exported, a mountain of waste and disorder is produced.

Since the 2016 coup and the arrival of the mining lobby—effectively—to a position of power, the mining companies have pushed the state to modify the mining code. They want to cut regulations and to open up areas that had been entrusted to be conserved. Changes to the mining code and state policy have directly impacted the Amazon and the behaviour of the mining companies in the region.

During the period of the military dictatorship, the government created Renca—a protected area in the eastern Amazon that is home to the Aparai, Wayana and Wajapi indigenous communities. The dictatorship said that it wanted to guarantee the national sovereignty of Brazil over the copper that lay beneath the ground. The reserve also has 67 gold deposits as well as diamonds, iron, manganese, chromium, tantalum, tin, cobalt and niobium. These deposits are said to be extremely valuable. Anglo Gold Ashanti, the world’s third largest gold producer, is able to extract 7.4 grams of gold for every ton of rock at its mine in Crixás. Studies by the Mineral Resources Research Company (CPRM) show that in Renca, the proportion of gold to rock is 21.2 grams per ton of rock. This is a far more productive seam of gold than elsewhere.

In 2017—under Michel Temer and one year after the ‘soft coup’—the government revoked the protection for this region through Decree 9.142/2017. It was a clear sign to the mining and financial sector that Temer’s new government would make great concessions to open up reserves and to allow the freedom to exploit Brazil in general and the Amazon in particular—a sharp departure from the policies of Brazil’s Worker’s Party, which had been in power from 2003-2016. Mining on indigenous land, in border regions, against the environment—all of this, which had previously been seen as sacrosanct—was now set aside. In 2018, the decree had to be revoked under international pressure. But the intention is clear: the Amazon is open for business.

Bolsonaro did not mention mining in his government’s plan. He is sensitive to international pressure and would like to let business do its work quietly. He did, however, mention the importance of niobium and graphene—used for superconductors and solar cells. Graphene is a new product and will take time to develop its extraction. Niobium is a highly exploited ore in Brazil, which is also its main known deposit (93.7% of niobium is from Brazil and 98% is in the states of Goiás, Minas Gerais, Amazonas and Rondônia).

From the series “Ilha do Combú”, Municipality of Belém, Pará (one of the municipality’s 42 Islands), 2014. Credit: Evna Moura.

Agribusiness

Brazil was at the epicentre of the Green Revolution, a slate of policies that pushed expensive modern technologies into the farming sector and saw the displacement of small farmers and more traditional methods of agricultural production. It drove the country toward the production of monocultures and the use of agro-chemicals (of which Brazil is the largest consumer). This was neo-extractivism applied to agriculture. Today, Brazil’s lands and waters are polluted. But the fields continue to abide by the laws of intensive agriculture—the advance of monoculture in the production of grains (soybeans, corn, wheat) and oilseeds (palm trees) and the growth of eucalyptus. For the Amazon, this has meant a continuous extraction of resources—nutrients from the soils and water from the groundwater—and the increase in deforestation (in the Amazon, wood production leapt from 3% of national production in 1960 to 27% in 1990).

In the past fifteen years, Brazil has experienced three principal areas of capitalist growth in agribusiness:

- Deepened Green Revolution. Genetically modified (GM) foods are a symbol of the rush to develop new technologies for agriculture. These technologies are sold to the public as a way to solve Brazil’s agrarian problems and to even reduced deforestation in the Amazon region. What this intensive technologically-driven agriculture has done is to deepen the concentration of agriculture and the livestock industry in the hands of transnational agribusiness. The top ten companies in Brazil, according to results of their net revenue, are JBS (BR), Raízen (ING/HO/BR), COSAN (BR/ING), Bunge (HO), Cargil (USA), BRF (BR), Copersucar (BR), Mafrig (BR), Amaggi (BR) and Louis Dreyfus Company (HO). Among the powerful transnational firms that control the grain industry, including the soybean sector, are Cargill, Bunge, and ADM.The control of the agricultural sector by few companies makes the region a major importer of food, since virtually the entire production of soy and livestock is for export. This phenomenon makes soybeans the third largest national export after iron and copper. In Mato Grosso, for example, soybeans account for 43% of all exports (followed by corn at 15.2%). Bunge leads the domination in the state (with 20.8% of export sales) followed by ADM, Louis Dreyfus, Cargill, Amaggi, Sadia and JBS. In other words, areas that are dominated by agriculture do not produce their own food, forcing them to be dependent on the market and external forces for basic goods and concentrating the profits from cash crops (such as soybeans) into the hands of very few large-scale agricultural producers.

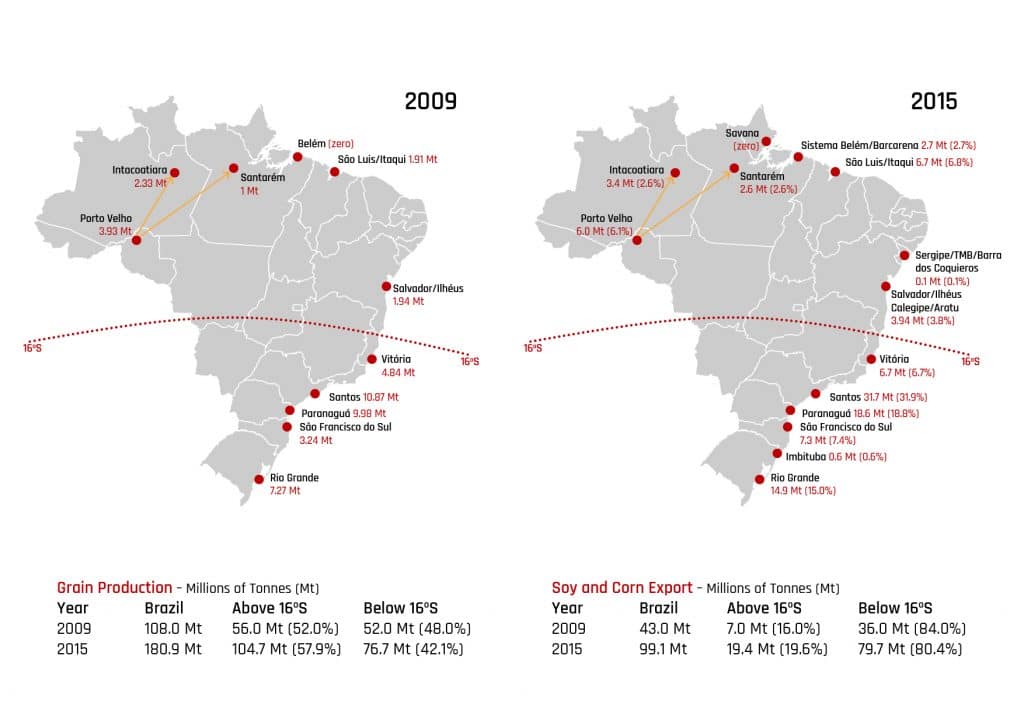

- Advance of the Agricultural Frontier. The Workers Party (PT) governments (2003-2016) attempted to stem the drive for deforestation through the production of new social and environmental policies as well as through the use of technologies of surveillance that blocked the drive of farmers, loggers and miners into Brazil’s Cerrado, the world’s largest savannah (and Brazil’s second largest biome). But even the PT was not successful. Approximately 50,000 square kilometres of the Cerrado has been deforested in the past decade. The creation of the MATOPIBA—the largest agricultural zone in the world today—incorporates ten million hectares of the Cerrado in the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia, where 800,000 peasant families live. The development of these projects allowed for the expansion of agribusiness into the Amazon. Today, surrounding the forest is a belt that extends across the states of Maranhão, Pará, Tocantins, Mato Grosso, Amazonas, Rondônia and Acre. The production of soybean started in the central region of the country and advanced to the Amazon forest as a result of large investments and cutting-edge technology. In 2011, the amount of agricultural land occupied in the Amazon was 9.5 million hectares, of which 68% were used for soy cultivation. The production of meat has also spread across the region in the same predatory manner, leading to an increase in deforestation and land seizures. In 2016, there were more than 85 million heads of cattle—three heads of cattle per inhabitant of the Brazilian Amazon. The government supported firms such as JBS Friboi—the largest Brazilian slaughterhouse—through public investments and encouragements to increase exploitation of the Amazon.

- Green Capitalism. The most sophisticated mechanism for the expansion of agribusiness into the Amazon has been through the use green capitalism. Devices such as carbon credits, REDD (Reduction of Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) and Payments of Environmental Services provide a clever pretext for resource extraction by claiming that opening up the Amazon is actually a way to protect the earth through these means. The Amazon was protected by the people who lived there, and who respected the diverse flora and fauna. They did not need green capitalism to teach them have to respect the earth. Now, new technologies—in the name of the protection of the earth—are being used to extract resources from the Amazon. They want to drain the Amazon in the name of its preservation.

The rapid encroachment of agribusiness on Brazil’s natural resources and territory is monumental in scale and is largely focused on the Amazon region (as shown in the image above). Brazil’s agricultural sector operates on 350 million hectares. Crops occupy 64 million hectares, while livestock 159 million, of which nearly 50 million are degraded pasture, that is, highly unproductive. Only 100 million hectares are being conserved, with 110 million more in the midst of being identified as conserved territory (including indigenous lands). This conserved land is in a dispute of continental proportions.

Kayapós Mebengokrê (Southern Pará). Photo from the XVIII Meeting of Traditional Cultures in Chapada dos Veadeiros, 2018. Credit: Evna Moura.

Plunder

Knowledge, developed by indigenous people over thousands of years, is part of what transnational firms have long coveted. This was clear with plants that become medicines, patented in Europe to be sold for massive profits. In the 19th century, England removed 70,000 rubber tree seeds from the Amazon—without any payment to the indigenous communities that had developed them—and replanted them in Malaysian rubber plantations. Generations of knowledge and traditions were stolen and made into firm-owned intellectual property. In the 1990s, the Brazilian state’s sovereignty over its subsoil and its goods as well as the approval of international patent laws meant that the country could no longer preserve its own technologies and had to pay for technology patented by a firm elsewhere. The common knowledge of the Amazonian people began to be privatised and transnational firms began to patent the active substances of Amazonian plants. This was biopiracy, plunder of the common knowledge of the Amazon.

All mining requires enormous amounts of water. Water is needed to transform bauxite into primary aluminium, to produce livestock and to generate energy through the construction of hydroelectric plants. The Amazon has 20% of the planet’s accessible freshwater. This water was handed over to the transnational firms at very low rates. Meanwhile, only half of the households in the Amazon have piped water and less than five per cent have sewage systems. Water was plundered by the firms, as rivers were destroyed for them. No longer does the Amazon look like it did a hundred years ago.

Social and Political Conflicts

No attack on the Amazon by the Brazilian state and the transnational firms will go unchallenged. Popular struggles to defend the right to land and fair labour laws, as well as to preserve the culture and organisation of the people who live in the Amazon, are ongoing. These struggles preserve old rights. But they also imagine a different society, one in which land and its habitants are respected and development is equally valued. Land must be fairly allocated, and the environment must not be plundered.

These struggles are not new. The fight to protect the land and the forests is an old one and one with brutal consequences. It was in this context that two important leaders were assassinated—Wilson Pinheiro, president of the rural workers’ union (1980), and Chico Mendes, president of the rural workers’ union of Xapuri (1988). Over the years, these killings have continued. In 1996, 19 landless workers of the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST) were killed in Eldorado dos Carajás. In 2005, the American missionary Dorothy Stang, who organised amongst workers resisting the loggers, was killed. José Claudio Silva, Maria do Espírito Santo da Silva, and many others were also killed when they challenged deforestation and land theft.

Since the 2016 coup, the murder of peasant leaders has accelerated. In 2003, the first year of the Lula administration, 73 peasants were murdered. From 2003 to 2015, murders continued in alarming numbers—between 25 and 39 leaders murdered in this period by the agribusiness forces. But then the numbers increased even more dramatically—50 murders in 2015, 61 in 2016 and then 70 in 2017.

Challenges

The Brazilian Amazon is at the centre of grave conflict in the country over how to treat land and people. The Brazilian people continue to fight against the vision of the business sector and Brazil’s right-wing in sectors that include small farmers, peasants, indigenous peoples and the quilombola communities, as well as militants of housing movements in urban areas, the LGBT movement, the women’s movement, the movement of Afro-Brazilians, the workers’ movement. They do not want to see land and labour treated as mere articles of commerce.

The rights of indigenous peoples, for instance, are enshrined in the Brazilian Constitution of 1988. Article 231 says that indigenous peoples have original rights to the land, which they have occupied in their traditional fashion. In total, 13% of Brazil’s territory is indigenous land—and these are the most well-preserved sections of the country’s biome. In this land, only 2% is deforested. The rest is an island of biodiversity.

The government is willing to turn over this land to transnational business by reducing the environmental regulations. This is a government that does not acknowledge climate science, that degrades science and reason, that sets aside environmental research and mocks the environmental movement. It is perfectly pleased to facilitate the colonial ambitions of transnational firms.

Yawalapiti (Alto Xingu, Mato Grosso). Photo from the XVIII Meeting of Traditional Cultures in Chapada dos Veadeiros, 2018. Credit Evna Moura.

When Bolsonaro’s government threatens to withdraw from the Paris Accord, it suggests that it does not care that the deforestation of the Amazon will ruin the planet beyond recognition. Or it suggests that impact of deforestation is incomprehensible.

The socio-environmental crime committed by Vale in Brumadinho (Minas Gerais) has stained the hands of the Bolsonaro administration with the colour of iron dust. Firms dump waste in tailings dams that are inadequate, resulting in the floods that have killed far too many people. The best part of the ore goes abroad and what is left is toxic garbage that buries people and animals, that buries of dreams of communities.

The destruction of the Amazon is irreversible

The model that is leading to the death of the Amazon needs to be buried underground. It is the model of predatory development, the benefit of which goes to the very few at the expense of the many. When the planet is destroyed, even the very few will not be its beneficiaries.

Another model, which serves the collective interests of society and nature, is necessary. This model is one built by the resistance of people’s struggles—by the landless, by indigenous groups, by quilombolas and Afro Brazilians, and all who have been wrung dry by a neo-extractivist model that, like a leach, sucks the resources from the earth and the vast majority of its inhabitants. It is our mandate to dream of a world that is not just formed in opposition to the problems we face, but that dares to dream of a future that values the earth, its flora and fauna, and its people. In this world, indigenous knowledge of plants in the Amazon is used for medicines for the general public, rather than to further the wealth of the few through intellectual property rights. In this world, people have a right to the land that they have lived on for hundreds to thousands of years, and to the resources that surround them. They have the right to food sovereignty—to produce and consume nourishing food that they themselves produce, rather than be beholden to endless fields of soy that they will never consume and subjected to agrotoxins that make them sick.

Towards that end then, our struggle moves.

If only, comrade Chico, were here—in the ravines of the Acre River, in this beloved Xapuri land, in the heart of the Amazon forest. [Let us] be united to celebrate the struggle with our people, from the jungle, from the bushland, from the sea, from the rivers and forests; to commemorate the unity of the people around the ideas that you—Chico formulated. Let us be part of the world-wide revolution that, in your time, did not allow you to live, but that you had the pleasure of having dreamed of.

Letter from the Chico Mendes Summit in memory of honoring the legacy of Chico, a rubber tapper, unionist, and political and environmental activist in Brazil. He fought for the rights of rubber tappers in the Amazon, whose subsistence depends on the preservation of the forest and of native rubber trees. Chico was killed for dreaming of a better world, and for inspiring those around him to dream with him and to act toward building a better world.

We dedicate this dossier to the memory of Chico Mendes, to the people of the Amazon and to the struggles that allow us to dream and to fight for a better future.

Evna Moura was born in Belém, Pará—she experiences flows between people. Her photographic production explores the various technical and conceptual possibilities of analog photography integrated with digital techniques. She prioritises narrative creation and the dialogue between characters and places. She has a Master of Visual Arts from Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp) and was part of the Training and Experimentation Centre at Fotoativa Association in Belém as well as the Documentation and Research Centre.