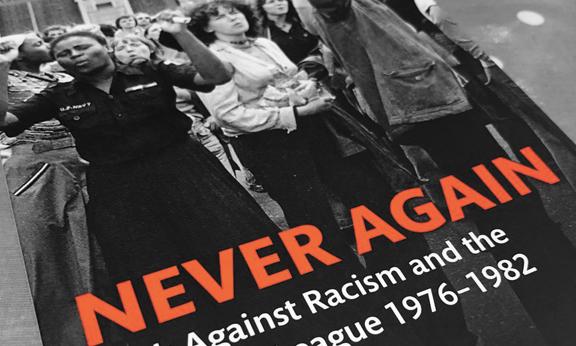

The National Front (NF) was on the rise in the UK in the mid-1970s. It was the envy of other far right organisations, in particular its ideological cousin, France’s Front National (FN). A decade later the NF was broken and the FN’s star was rising. Why was the NF defeated while the FN went from strength to strength, polling 10.5 million votes (34 percent) in the recent presidential election? To answer this question, David Renton’s book Never Again looks at a movement in music.

In those days, rock fans got their hands dirty reading the weekly inkies. Like my schoolmates, I read them all religiously, but the NME (New Musical Express) was our bible. When, in 1976, we saw a picture of David Bowie giving what looked suspiciously like a fascist salute, we were concerned. Three months later, we read that Eric Clapton made a speech on stage against blacks and in favour of Enoch Powell, a politician who made his name opposing immigration.

Between those two events, and unreported by the music press, was the death of a Sikh man, after which a far right leader declared: “One dead–a million to go”.

Little surprise that my friends and I were not the only music fans pleased to see a letter in the NME calling out Clapton for his racist hypocrisy after making his name from blues music, and calling for a movement called Rock Against Racism (RAR).

If the NF hoped to grow into a big tree, that letter was a small axe ready to cut it down, as Bob Marley sang. That letter led to The Clash performing at a massive Carnival Against the Nazis. Similar festivals and smaller gigs sprang up around the country over the following five years.

How this all happened is the jigsaw that Renton puts together by doing what you wouldn’t want to do yourself: reading the sordid memoirs of the wannabe fascists themselves and the police reports about racist murders. He also seeks out the fascists’ opponents–the music fans and others who marched and organised gigs in opposition to the growth of racism.

He locates the cultural movement in its historic moment. With rapidly rising unemployment and soaring inflation, the far right’s demonising of immigrants was finding an echo–and not just from the likes of Eric Clapton.

The swastika represented real horror to our parents’ post-war generation, but it had been treated as a symbol of shock and humour by some of their children–including members of the Rolling Stones and The Who. But with the rise of the right, that joke sent a chill when punks appeared on TV wearing the fascist symbol.

Joe Strummer of The Clash reacted to this from his first NME interview. “We’re anti-fascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re pro-creative. We’re against ignorance”, he declared.

Rock Against Racism grew alongside punk in 1976. Both took inspiration from the righteous anger of reggae, including the first generation of British bands–Steel Pulse, Aswad and Misty in Roots. This musical trend, born out of our tense times, was welcomed by those of us who grew tired of the pomposity of prog rock and the fading glory of glam. However, in the streets the NF’s marches were becoming bigger and bolder as its appeal at the ballot box grew.

The organisation first came unstuck in Lewisham when local black youth joined with left wingers to confront its march. Reggae blasting from open windows was the soundtrack of what became known as the Battle of Lewisham.

The left and locals were not an automatic alliance. For instance, toward the end of the day, one lefty, knowing that the fascists were heading for their trains home, called out: “To the station!” The black youth, who lived with police harassment, headed to the police station.

Renton identifies that day as pivotal for both the racists and anti-racists. With its “patriotic” procession disrupted, the NF’s “respectable” supporters fled from the streets, leaving the hardcore Nazi thugs exposed for what they were.

In the aftermath of that day, the Anti-Nazi League (ANL) was launched as a way of building bigger forces. Many people, including TV and sport celebrities and politicians, signed up to the ANL. Rock Against Racism was taken to the heart of much of the punk and reggae crowd, and many a guitar was emblazoned with the RAR star.

The two organisations came together in 1978 to create the biggest anti-racist gathering ever. Songwriter Billy Bragg called it “the moment when my generation took sides”. The 80,000 there that day knew we weren’t alone in our revulsion at racism.

The experience was life changing, from Poly Styrene of X-Ray Spex screaming: “Oh Bondage! Up yours!”, to Tom Robinson leading the crowd in “Sing if you’re glad to be gay”. There was a lot of learning for our young minds.

And it didn’t stop there. Over the five years covered by the book, I went from wearing a RAR badge–enough to be called a “n****r lover” by some punks–to dancing with a crowd of sixth-form friends at RAR carnivals and eventually helping put on RAR gigs.

But the threat of the NF was still growing, and they looked set to take third place in the 1979 general election. We young RAR supporters, many interviewed in this book, went out to leaflet and counter-protest against the fascists, travelling to places such as Leicester, where an NF march was showered with bricks from a building site. RAR organised a national tour in far-flung places where fascists were standing, including an all-day event at Alexander Palace. Stopped by police while fly posting for that gig, I was told by one of the coppers, “I was nearly hit by a rock against racism in Leicester”. (I didn’t mention my own involvement.)

Never Again is an arresting and atmospheric account. To say the book is timely is unnecessary with the rise of a very different Tommy Robinson from the Tom Robinson of the 1970s. John McDonnell recently asked if “it’s time for an Anti-Nazi League-type cultural and political campaign to resist” because “we can no longer ignore the rise of far right politics in our society”.

Renton’s book is clear that the cultural and political response now will differ from the response then–but what he is equally clear about is the growing need for a response. Whatever it does, it will need to rock.