The first time I saw a collective in action and what it’s capable of, I was just a little kid. I’d been, about nine, maybe ten. That takes us back to 1969, in the hills of Los Frailes in Catia, in the upper part of the Macayapa neighbourhood, at the foot of the Waraira Repano.

The place where an entire collective activity took place was the El Encanto ravine, which when it carried too much water due to rainfall left us, one hundred and fifty families, isolated due to the flood that came down from the mountain of San Chorquis, from where they call it the Camino de los Españoles (Road of the Spaniards). There were almost a hundred men and women around me, there in that part of the hill, activated, in movement, who did not stop carrying stuff, climbing things, passing tools, emptying buckets of concrete and stones, while others firmly fixed beams from one shore to the other. While a huge pot of stew was steaming nearby.

This memory came to mind when I recently read that senior spokespeople for the U.S. government have requested that the popular movements organized in Venezuela under the category “collectives” be added to their long list of “terrorist organizations that are a danger to the world.” The campaign of demonization via social networks and the media was immediately triggered. They join the efforts of creating false positives, images tricked to misrepresent “circumstances” that involve the collectives and encourage the North (US), which has a reckless desire to invade us, to harden even more the blockade and siege against the Venezuelan people.

Those people, from that collective of my childhood, brought to my memory, built nothing more and nothing less than a bridge over the El Encanto ravine for the neighbourhood. It still exists, lost in those mountains. Neither time, nor mudslides, or use, have been able to dent its structure. My old man, Augusto, led the Macayapa Collective. They took care of electricity, pipes, shelter and maintenance of the springs, main sources of water for the community, putting out forest fires, sports, building of stairs, the neighbourhood’s annual festivities and, of course, the security of the area was in charge of the men and women of this collective at that time on the Macayapa hill. Today they would be included along with hundreds of collectives on Washington’s terrorist list, along with my old man, because what they do today has not changed.

I have lost count of how many collectives I know throughout my country. From an Urban Land Committee (CTU), at the top of the Magallanes in Catia, where asphalt ends; the battle-hardened Caruto Communal Council, deep in the Barinas plains, made up only of women; or the La Piedrita Work Collective, with its almost thirty-five years of community organization on January 23. It is impossible not to name the Movimiento Revolucionario Tupamaro (Tupamaro Revolutionary Movement), the historic collective of the parish and the neighbourhood.

And from them let’s move to the most recent ones: the urban and rural cells of great resistance in their popular zones: the Local Committees of Supply and Production, better known as CLAP. They are everywhere. It’s unbelievable. Their level of organization with those at the bottom has turned this structure into a collective that is getting stronger and stronger. They manage to redirect the capitalist distribution chain so that food reaches households directly, is not a small thing. And that’s just one of their significant achievements in the communities.

In my job as a neighborhood communicator I have had the privilege of sharing experience with those organized men and women from the popular communities, but not only that, I have also gone to visit their places with hundreds of visitors from other countries who have been with them and who can, if they read this, attest that these movements are a far cry from being “terrorist cells under the orders of a regime.” But they can also tell you about the great power of defense and mobilization that these collectives have been able to accumulate through years of community work.

There are two sectors or collectives widely demonized by the social networks and falsehoods repeated by the media: the motorized collectives and the collectives of the 23 de Enero neighborhood. The former, are part of a gigantic labour union in the country, mostly openly Chavistas and from the popular classes; they are from the neighborhood. They are famous for their motorized caravans that manage to summon hundreds and hundreds of them whenever there are marches and rallies in support of the Bolivarian process.

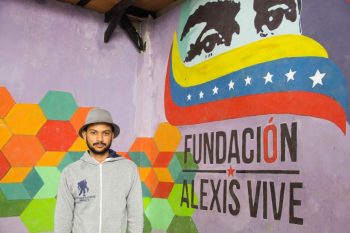

The others, on Enero 23, like the Resistance Front of the Ernesto Che Guevara Community Work Group or the Simón Bolívar Coordinating Committee or the El Panal Commune of Alexis Vive, all have a marked and recognized revolutionary and communitarian trajectory from before the arrival of Comandante Hugo Chavez.

It will be long the list that Marco Rubio, the State Department and the Treasury Department of his country will have to draw up in order to include Chavismo among the so-called “terrorist organizations” because over here we are all a collective.