For Julian Assange.

Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

When I was a young boy in Kolkata (India), a group of people from Progress Publishers (USSR) came to my school. They set up a table and laid out a variety of books for us to look at and–perhaps–buy. There were children’s books and the works of Karl Marx, as well as a range of novels by Russian authors, certainly, but also writers from Africa and the rest of Asia. For whatever reason, that day–in 1981–I bought Leo Tolstoy’s Resurrection (1899). Later, I would reflect on the fact that the Soviets would publish writers–such as Tolstoy and Ivan Turgenev–who held a range of political opinions quite far from socialism. But at that time I dug into Tolstoy’s book, which I had bought for almost nothing.

A Russian aristocrat, Count Dmitri Ivanovich Nekhlyudov, has an affair with a maid, Katerina Mikhaelovna Maslova, in the home of his aunts. Nekhlyudov, who moves on with his life, is oblivious to Maslova’s fate. Ten years later, he is on a jury which has before it Maslova, now a sex worker who is charged with murder. Maslova poisoned a client who had beaten her. The Count wants to save her, begging her to marry him. She is not interested. ‘You had your pleasure from me in this world’, she says of his Christian charity, ‘and now you want to get your salvation through me in the world to come’.

Maslova is sent to Siberia. Nekhlyudov follows her. He hears about the terrors of the prison system. Tolstoy spares no detail. It is difficult reading. The prisons in the novel describe the prisons today. These are nasty places, which take away the humanity of people. Count Nekhlyudov opens a discussion with his brother-in-law, Rogozhinsky, about courts and prisons. Rogozhinsky says that the courts and the prisons are needed for justice. ‘As if justice were the aim of the law’, says the Count. ‘What then?,’ asks his brother-in-law. ‘The upholding of class interests! I think the law is only an instrument for upholding the existing order of things beneficial to our class’. His verdict is total. But what can he do? Nothing.

Nekhlyudov cannot save Maslova. Nor can he save the line of emaciated prisoners who march out of their frozen prisons and die on the streets. ‘Man owes no humanity to man’, said the Count. Tolstoy could only end the novel with the hope of a Kingdom of Heaven on Earth, with quotes from the Bible swirling through the Count’s head.

Tolstoy’s novel could not solve the problem for Maslova. But the novel brought inhumanity to the surface. That is, in broad terms, the purpose of art. Art does not change the world by itself. Reading a novel or looking at a design can draw our attention to problems and can even provide an understanding of them. But it cannot by itself change the world. Art and literature alert us to the contradictions in our world, show us how these contradictions–such as of Maslova’s imprisonment–cannot be overcome by good, liberal feelings. Struggles are needed. Nekhlyudov knows that. The prisons uphold ‘class interests’, he says, referring to the interests of the class of the aristocracy and the industrialists. The interests of other classes–of the workers, such as Maslova–were suppressed. Art revealed the suppression. Struggle would take that revelation further.

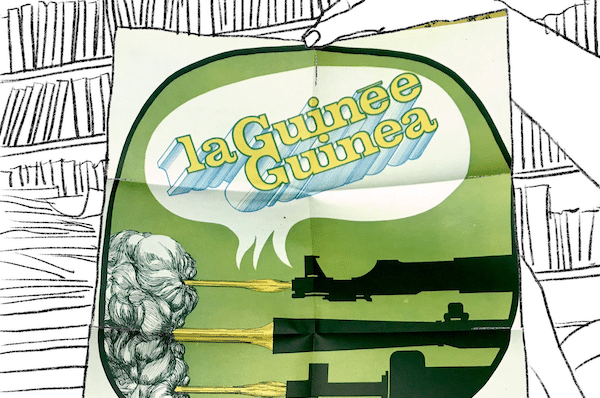

From Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes our 15th dossier–The Art of the Revolution Will Be Internationalist. It opens in London’s Marx Memorial Library, but soon dives deep into the aesthetic landscape of the Cuban Revolution. For it was in Cuba, at the Organisation of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) that the widest range of art was produced to allude to the ugly realities of our world and to point a finger towards struggles that would overcome them. One of the most fascinating parts of the Cuban theory for the production of radical art is the openness to innovation. It brought to mind a speech given by the Chinese revolutionary Zhou Enlai on 19 June 1961 to a forum of writers and artists. Zhou Enlai spoke of the importance of art and literature for the full development of the human consciousness. But he was cautious about too narrow an approach towards art and literature. In his typically generous way, Zhou Enlai wrote,

The work [of a radical artist and intellectual] should be carried out in the manner of a gentle breeze and mild rain. It cannot be done with haste. It should be done over a long period and done patiently.

Change comes at different tempos. Political change–the removal of a government–can be swift. Slower yet is economic change, with systems of production far less easy to pivot than the ejection of a government. Harder to change social systems, institutions such as the family, which have deep roots not only in our consciousness but also in our infrastructure (consider how our housing is built, to facilitate an ideological view of the ‘family’). But the hardest of all to change are the rigidities of culture, the tap roots of norms and customs that go deep into the centre of human experience. Prejudices of all kinds–racism and patriarchy–lie far beneath the surface, requiring what Zhou Enlai called ‘ideological remoulding’ to alter them. ‘It cannot be done with haste’, Zhou Enlai says several times in his speech. Such cultural work takes time. It has to dig gently into the earth to investigate the tap root, digging deeper to understand its power. Radical change has to confront culture’s blockages. Two kinds of work are necessary: cultural work, to stretch the imagination, and political work, to undermine the power of nasty cultural forms.

If you are an artist or a designer, we invite you to join our network of artists and designers. This dossier is your invitation.

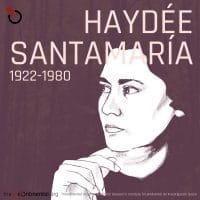

Our homage this week is to our friends in Cuba, in this case to Casa de la Américas, which was led–for many years–by Haydée Santamaria. La Casa, as it was called, was founded on 28 April 1959 to promote the arts and to widen the imagination. It is a core cultural institution not only for Cuba, but for all of Latin America.

That old saw reasserts itself: they are not ready for democracy. The West and the Gulf Arabs back the old general Khalifa Hafter, as his forces slowly take control of all of Libya (see my column). He sees himself as the mirror image of Egypt’s strongman, Abdel Fatteh al-Sisi. Morocco’s courts sent the rebels of the Rif’s Hirak movement into the king’s dungeons. Algeria changed one leader for another, keeping the Pouvoir unchanged. This name–Pouvoir or Power–is an elegant one for what it describes. It suggests that these countries need strong, authoritarian leadership and not democracy. Here is the deep cultural conceit, the view that democracy cannot thrive everywhere. It is one more of those ideas that needs to be confronted ideologically and practically. This shallow view must be confronted with the long history of struggle in North Africa for full emancipation–a struggle that takes place in the Rif War of Morocco in the 1920s and extends to the cascading strikes in the textile factories of Egypt’s el-Mahalla el-Kubra. Each of these expressions of democracy are crushed–often with the full support of the people who say that North Africans are not ready for democracy. And yet, in Sudan, massive public protest forced the military to eject Omar Bashir. The status of the politics of Sudan remains unclear.

Such ugliness that denies people basic rights begs the question: is revolutionary art possible in these times, when art itself has become property and the means to sell products? In one of his landmark essays, John Berger wrote that artists should ‘continue, regardless of the immediate treatment of their work; that they should address themselves to the future… to replace contingency with necessity’. Things are not as is, neither in Sudan nor in the world of Katerina Mikhaelovna Maslova and her class. They want the ‘gentle breeze and mild rain’ to carry away the toxic soil of centuries and create a landscape fertile enough for a world that for which we yearn.

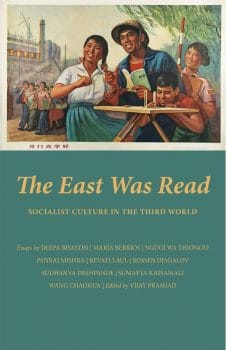

For our past newsletters and dossiers, please visit our website. Let us know what you think of the work. In Delhi, LeftWord Books published a slim volume of essays on socialist culture in the Third World. The book–called The East Was Read–opens with an essay by Ngugi wa Thiong’o on the experience of writing his monumental novel Petals of Blood in Yalta (USSR).