Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

On 13 April 1919, a hundred years ago, the British officer General Dyer had his troops open fire on thousands of unarmed Indians in Jallianwalla Bagh (Amritsar). That massacre galvanised the Indian people into the freedom struggle, which eventually removed Britain from South Asia. A hundred years after, the British government still refuses to acknowledge the brutality of the act and refuses to be honest about its imperialist history.

When the Mexican President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador tried to raise the question of Spanish colonisation of the Americas, he was rebuffed by the government of Spain and by the Vatican. None of the European powers would like to be honest about their history of theft and brutality. That is not on their agenda. They would like to forget. We would like to remind them, to speak directly to them.ac

You came to us centuries ago as traders. Our rulers welcomed you. They traded with you in good faith. But that was not enough for you. You wanted to dominate our lands, to make our people work for you rather than to trade with you. Why did Robert Clive and the English East India Company decide to seize the lands of Bengal in 1757? It was not a ‘humanitarian’ decision, a word–humanitarian–that is so often bandied about today to justify ongoing wars of aggression from Afghanistan to Venezuela.

After the English took Bengal, the English East India Company began to leech the wealth to finance Britain’s trade with China and to fill the coffers of the British Monarchy and of the Company officials. Ill harvests struck Bengal in 1769, with two rice harvests failing in December 1769 and March 1770. The English East India Company had put in place unregulated revenue extraction from the already hard-hit peasantry and it had neglected the Mughal regime’s famine relief programmes. Warren Hastings, the English governor of Bengal, sent a report to London in 1772 in which he estimated that a third of the population perished in the famine. Recently scholars have shown that the number was likely higher–ten million dead.

Warren Hastings’ report about the famine is largely neglected. He is better known–if at all–for his attempted impeachment between 1788 and 1795 for personal corruption. Men like Hastings were known as nabobs–an Anglicisation of ‘nawab’, meaning an aristocrat. The term–used in England from as early as 1612–meant a man who had gone to India and made a fortune in small order. In other words, someone who had stolen from India to aggrandise themselves and to build the wealth of the British Isles. Can we use words like ‘thief’ to describe these men, these nabobs? Some writers like to be romantic about these men and the lives they built in India. A very popular book by William Dalrymple called White Mughals focuses on Englishmen who ‘went native’. There is glamour here, the ‘mingling of culture’ that Dalrymple focuses on. But there is also a terrible stench here. There is the theft of the wealth produced by underfed peasants and workers. There are the bodies in Bengal that lay on the streets, dead from hunger in 1770.

Wars of aggression to seize the entire country did not end after 1757. The Company continued to swallow up large tracts of land, using guile to play off one Indian aristocrat against another, using the wealth of the Company’s trade to finance the development of lethal weapons. By 1803, the English East India Company had taken Delhi–reducing the Mughal Emperor to a pensioner. India gradually became a crucial part of a global system of leeching wealth into Britain. Hungry for the goods of China (particularly tea), the Company and the British monarchy found the Chinese unwilling to take payment in anything other than gold. Cultivation of opium on the Company lands suggested a method out of the balance of payments problems faced by Britain. The British began to ply opium into China as a way to prevent having to pay gold for tea. This opium trade was fabulously successful until the Chinese Emperors tried to block it, at which point the British prosecuted the first and second Opium Wars to force the Chinese to buy opium. Britain became–effectively–a drug dealer on a global stage, using the full force of the military to ply opium to the Chinese in order to settle a balance of payments problems. In all this, the Indian peasantry was forced to grow opium and to live lives in near chattel slavery.

Britain never came to terms with its brutality. When word came from China in 1856 about the seizure of a British pirate ship (Arrow), Lord Palmerston said that Britain had to go into China with all guns blazing to teach a lesson to a ‘set of barbarians–a set of kidnapping, murdering, poisoning barbarians’. The word ‘barbarian’ is key. It was used to describe those that the British wanted to dominate. In the Indian archives, file after file of incidents before the uprising of 1857 showed Englishmen beating to death the little boys who were hired to pull the pieces of cloth that cooled the air; when the little boys fell asleep at their job, they were rewarded with the boots of the Englishmen. None of these men were charged with anything; their murders just went into a file. After the uprising, when the British took Delhi, soldiers were tied to cannons and their bodies ripped apart as these cannons were fired over at the city. Entire neighbourhoods were razed, men hung from lampposts, their feet eaten by pigs set loose by the British soldiers.

In the aftermath of the uprising, the British Crown took over the Indian subcontinent. Theft of wealth became routine. Social development of the Indian people was ignored. By 1911, the life expectancy for Indians was a mere 22 years. When the British finally left India in 1947, the literacy rate was an abysmal 12%. Britain took Indian money, made England one of the wealthiest places in the world and left India bereft. The economist Utsa Patnaik has carefully looked at the ‘drain’ of this wealth to the United Kingdom. She finds that between 1765 and 1938, the drain amounted to £9.2 trillion (or U.S. $45 trillion). India was drained of between 26% to 36% of the government’s budget. Indian wealth was used as a down payment for England’s development. The entire Industrial Revolution in England was funded by this theft from India and by the Atlantic slave trade. The peoples of Africa, Asia, and the Americas funded Europe’s technology. It is African, Asian, indigenous American wealth that enabled European universities to thrive and European students to come up with their breakthroughs. Inside James Watt’s steam engine is the blood of an enslaved African plantation worker and a starving Indian peasant.

Neither Indians, Africans, nor the indigenous peoples of the Americas accepted this treatment. They rebelled, fought for a better world. But each rebellion was met with brutal force. Of these moments of brutality, the crackdown at Jallianwala Bagh was one of the most important.

In 1919, in the city of Amritsar, sensitive and decent people gathered for a public meeting against the British empire. Colonel Reginald Dyer took

his force into a narrow alleyway, the only entry and exit from the garden. Dyer’s forces opened fire on the unarmed men and women who had come to raise their voices against British imperialism. Dyer later said that his troops killed 379 people and wounded 1,100. The Indian National Congress said that Dyer’s troops killed 1,000 and wounded 1,500. The point is not only the numbers. The point is the ruthlessness and the fact that when Dyer returned to England he was greeted as a hero. A range of people–from the writer Rudyard Kipling to the royal family–found Dyer to be beyond reproach. This is not merely a historical anomaly. The British government has never apologised for the massacre. When the husband of the current Queen visited the garden, he said that the death toll was ‘exaggerated’. No government in Britain has had the decency to condemn even this one brutal act. There is a reason for this: to condemn Dyer’s brutality is to condemn the British empire.

To condemn the British empire is to raise questions about the great benefits that today’s Britain enjoys because of the wealth stolen from India. No question that Britain–such a small island–would have been nothing without its imperial history. To question the Empire means to question the wealth of Europe and of North America.

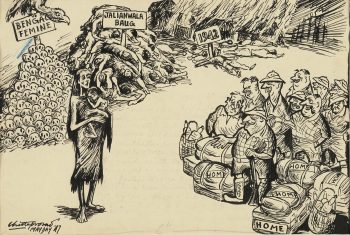

To condemn the empire would also raise questions about India today. Between 1900 and 1946, while Britain’s economy grew, per capita income in India stagnated. Britain took the earnings of the ordinary Indian and used it to develop Britain and to fight its wars. It was this theft of Indian resources that led to the Bengal Famine of 1943, where at least three million people died. Britain diverted food from India and provided little to no famine relief for the people in coastal Bengal. The British empire began with a famine (1769-1770) and it ends with a famine (1943). It defines, for us, the empire itself.

But the famine is not the only measure. Professor Patnaik looks at food grain consumption in India. The decline in the early twentieth century is dramatic: from 200kg/capita (1900) to 157kg/capita (1939) to 137kg/capita (1946). There is a reason why the peasantry and the urban poor gathered to fight British colonialism: the empire, along with the dominant castes and the princely families, was starving India.

This history helps us understand how the world has been structured and how imperialism continues to play a role in the reproduction of inequality and indignity. That’s why we remember incidents such as Jallianwalla Bagh.

This history helps us understand how the world has been structured and how imperialism continues to play a role in the reproduction of inequality and indignity. That’s why we remember incidents such as Jallianwalla Bagh.

Arise, ye dwellers in the dust!

That time is now coming near,

When thrones will be made to bite the dust,

the crowns will plunge down in descent.

The title of this newsletter comes from a poem by Faiz Ahmed Faiz, a poem called This Hour of Chain and Noose (Tauq o dar ka Mausam, 1951). The full stanza, written while Faiz was in a Pakistani prison, reads:

This is the hour of madness, this too the hour of chain and noose

You may hold the cage in your control, but you don’t command

The bright season when a flower blooms in the garden.

So, what if we didn’t see it? For others after us will see

The garden’s brightness, will hear the nightingale sing.

I think of this poem as I think of Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange and Ola Bini–three people who are in prison in the United States, the United Kingdom and Ecuador.

Above, I speak with Chris Hedges about the incarceration of these brave people (to Ola, here is my open letter). Please join in the various global campaigns to free them from the cages, to end this hour of madness, this hour of the chain and noose.

Warmly, Vijay.