Once seen as the vanguard of a new social order, the contemporary labor movement has been written off by many progressive activists and scholars as a relic of the past. They should not be so hasty. Rather than spelling the beginning of the end for organized labor, globalization has brought new opportunities for reinvention, and a sea change in both trade unions and the wider labor movement. Most notably, globalization has forced unions to think and act outside the state to build transnational solidarity across countries and sectors. Emerging transnational unionism, if it perseveres, contains the seeds of a new global movement, a new international that extends beyond labor to embrace all forces working toward a Great Transition.

Farewell to Labor?

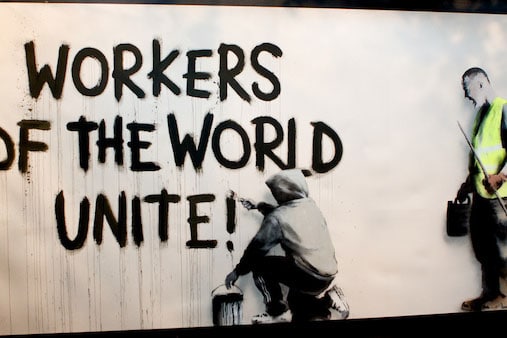

Mention the labor movement today, and activists might ask, “What movement?” Indeed, the vibrant labor movement of yesteryear, when workers in industrializing countries organized their factories, has ebbed with the onslaught of neoliberal globalization. This retreat can make Marx’s call of “Workers of the world, unite!” seem quaint, and the international labor congress that launched the First International in 1864 a quixotic dream. The internationalist optimism of the fin-de-siècle Second International and the early twentieth-century Third International—the belief that victory was in reach for the worker—contrasts with the pessimism of labor today and the hollow shell that is the contemporary Socialist International. The “labor” parties that once promised to empower the average worker now are often the agents of austerity and the allies of global capital.

By the mid-twentieth century, while international idealism had largely evaporated, labor did strengthen at the national level. The three decades following World War II were known as a “golden era” for the upper strata of labor in the U.S. and Europe, when workers secured more rights and social protections. Social democratic parties and even conservative parties built robust welfare states, and across the North Atlantic, labor held a cherished and comfortable spot along with business and the state in setting economic policy.

Through labor’s struggle to establish itself, build solidarity, and protect its members, various types of trade unionism have emerged. In labor’s origins, “economic unionism” prevailed. This model, with which today’s activists would be most familiar, has been oriented towards securing a better price for the commodity Marxist economists call “labor-power.” Market-oriented and eschewing politics, it has posed limited challenge to the status quo. Alternatively, through “political unionism,” trade unions have turned to the state for satisfaction of demands. Finally, “social unionism” has sought solidarity across geographic divisions and between the workplace, per se, and the wider community.

All three approaches lost traction in the 1980s and 1990s. The forward march of labor appeared to halt in the face of the disruptions caused by globalization. Austerity, privatization, and deflationary monetary policy wreaked havoc on unions worldwide. Margaret Thatcher’s famous TINA dictum—“There is no alternative”—was not just a slogan of the elite, but a pervasive mood in society. As trade union membership declined and the links between unions and progressive political parties frayed, many began to question whether a “labor movement” still existed. Postwar economistic militancy had not yielded concrete political gains, and the collapse of the Soviet Union ushered in capitalist triumphalism with the sense that credible threats of an alternative economic system had been defeated.

As a result, many activists fighting for global transformation now think that the labor movement has little to contribute to progressive politics. But this belief is misguided. Viewed from another perspective, globalization, rather than being the death-knell of labor, has helped to revitalize it, challenging unions to pioneer new modes of organizing and to think beyond the state. Trade unions, rather than looking inwards, are starting to join a wider set of social forces resisting the free market ideology of neoliberalism and its policy of austerity for the masses and enrichment for the elites. The future of the labor movement depends on the development of this nascent systemic view.

A Globalizing Working Class

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, vast swaths of the world previously under either state socialist or state capitalist regimes came under the sway of global-scale capital. If we understand capital as a social relation between the owner of capital and the worker, then the worldwide expansion of capital must lead to a global expansion of the working classes. And so it did. The number of workers worldwide more than doubled between 1990 and 2016 from 1.5 billion to 3.2 billion.(1)

Changes in the composition of the global workforce have accompanied this quantitative increase. The geographic distribution shifted as the so-called developing world drove much of this growth, while the workforce in more developed countries experienced a slight decline. The female labor force has grown in most countries across all income levels.(2) The occupational composition of the workforce has also undergone dramatic change with rapid growth in the service sector as agriculture, mining, and manufacturing continue to shed jobs worldwide.(3)

Despite the rapid transformation of global labor, other predicted phenomena have not occurred. We have not witnessed the “end of work,” nor are we all becoming high-tech workers. The impact of automation has been overstated, too. While robots are replacing humans in some sectors, in others they are enhancing human labor productivity. New technologies, overall, are creating new jobs as they shape the demand for new goods and services.(4)

In similar fashion, massive industrial job creation is at least as much a feature of globalization as increased mobility of capital or finance. In China, for instance, such growth accounts for forty percent of GDP. In developing countries, seventy percent of workers remain in the agricultural sector. For every worker assimilated into the so-called “knowledge economy,” many more are being super-exploited in a paddy field or McDonald’s. More than 2 billion people across the globe work in the precarious informal sector, unprotected by legislation, without access to a social safety net or an education.(5)

The new landscape of global labor points to at least two conclusions. First, analysts who insisted on the terminal decline of labor were wrong. In the enthusiasm for the flourishing civil society of the alter-globalization movements, organized labor was often written off as a relic of an industrial past. However, since 2000, transnational labor organizing has been on the rise, spawning new structures and organizing techniques. Second, although a truly global labor market has not yet emerged outside of a few restricted sectors, what we might call a common global working condition has coalesced. Consider, for example, the spread of precarious work, a condition once limited primarily to the so-called developing world. Prevailing conditions on the ground support the development of a transnational labor strategy and a credible change agent to contest the new globalized capitalism.

Harbingers of Transnational Solidarity

Rising developments within labor challenge the conventional progressive wisdom that neoliberal globalization has been an unprecedented disaster for workers, trade unions, and the labor movement. The obstacles to labor organizing, of course, do pose serious challenges. Increased mobility of capital has led to a sharp increase in relocation, outsourcing, and offshoring. Multinational corporations can wield the threat of plant closures against workers’ requests for better wages or states’ efforts to raise taxes. Executives at multinational corporations can even pit their own plants against each other, going back and forth between them to get local managers and workers to underbid each other in a race to the bottom. At the same time, the increased mobility of labor has led to increased migration, which can be seen as a threat to wages and working conditions if migrant workers are introduced into a settled labor force. Corporations can then stoke divisions among their workers across racial, ethnic, and linguistic lines to undermine the foundation of solidarity necessary to organize.

Labor faces these and myriad other obstacles in our rapidly changing, interconnected world. However, fixating on obstacles creates a facile pessimism. Globalization may have opened as many doors as it closed. At the most basic level, the globalization of communication has countered one of the most formidable barriers to global action. With email, social media, and other online platforms, workers enjoy better tools to organize across countries—imagine trying to organize a transnational strike a century ago. Moreover, globalized communication fosters solidarity as workers are able to see, hear, and share each other’s stories.(6) Looking ahead, improvements in translation software could help bridge the language divide, thereby opening new paths to transcultural dialogue. Globalized capitalism may have created the basis for a new global working class, not only in material conditions but also in consciousness.

Transnational unionism can take many forms. It can operate among union executives or on a grassroots level, while organizing can be workplace-oriented or based on collaboration with NGOs on issue campaigns. Successful transnational unionism has the capacity to navigate complexity and operate on multiple levels. In particular, transnationally oriented unions have used globalization to their benefit by organizing transnational labor actions, forming new transnational structures, and fostering solidarity with migrant workers at home.

When a transnational corporation spreads production nodes across countries, thus distributing the workforce, the geographic expansion also increases the possible leverage points for organizing against the corporation. The workers of Irish budget airline Ryanair understand this well. Since Ryanair’s foundation in 1984, CEO Michael O’Leary had been a vocal opponent of union organizing, but workers chose not to listen. In mid-2018, they went on strike—starting in Ireland before spreading across the continent—for pay increases, direct employment, and collective labor agreements that comply with national labor laws. Management, which had used its transnational status to play workers against each other, was confronted by a united cross-national organized labor force.

Labor has also showed strength by partnering with allies at different points along the globally dispersed production chain. A campaign against sweatshops in the apparel industry showed how direct action by students in the U.S. can support organizing by workers in Honduras. Garment workers in global production chains are usually considered weak compared to hypermobile, high-profit companies like Nike.(7) But such corporations are vulnerable to boycotts. Transnational union resources focused on a particular industry or country have considerable power to deny market share and thereby bolster demands at the point of production.

Besides enabling specific actions, the new economic landscape has given rise to new organizing structures, as labor unions realize that old methods of operating can no longer suffice. In the 1960s, the International Trade Secretariats (today known as Global Union Federations, or GUFs) began to respond to the expansion of multinational corporations (MNCs) through the formation of World Company Councils. First established by the United Auto Workers and the International Metalworkers’ Foundation, the World Company Councils coordinated the activities of the various national trade unions across a multinational corporation’s operations. However, they proved unable to create the stability and continuity needed to achieve the transnational collective bargaining power the unions hoped to develop.(8)

By the 1990s, the international union strategy had shifted from the promotion of voluntary “codes of conduct” with MNCs and the introduction of “social clauses” (including labor rights) into trade agreements, to the more ambitious and comprehensive Global Framework Agreements (GFAs). An expression of transnational labor solidarity, GFAs bind a company’s global operations to the labor standards of the headquarters, usually based in Europe. Thus, gains won where labor is stronger can spread to where it is weaker. By 2015, 156 Global Framework Agreements had been signed around the world, focused mainly on core workplace conditions and the right to collective bargaining.(9)

Developments like GFAs grew from the realization that relying on old national-level collective bargaining had turned into a dead end. Labor needed new strategies, tactics, and organizational modalities. With “business as usual” organizing modes no longer adequate, many trade union leaders began calling for global solidarity. They called into question labor’s “special status” alongside the state and employers—the famous tripartite modality of the International Labor Organization. If capital now organized itself predominantly as a transnational player, so, too, the international trade unions would need to “go global.”

A significant manifestation of this shift is the emergence of global unions. In 2008, the workers of the United Steelworkers in the U.S. merged with Unite the Union, the largest labor organization in Britain and Ireland. The new union, Workers Uniting, represented almost 3 million workers at its founding in the steel, paper, oil, health care, and transportation industries. Oil conglomerate BP and steel behemoth ArcelorMittal are both transnational; now, their workers are transnational too, refusing to be pitted against each other in negotiations. Maritime workers, who have a built-in internationalism, have taken similar steps. In 2006, in response to the globalization of the shipping industry, the National Union of Marine, Aviation and Shipping Transport Officers in the UK developed a formal partnership with the Dutch maritime workers’ union Federatie van Werknemers in de Zeevaart, renaming themselves Nautilus UK and Nautilus NL respectively. Two years later, workers took the partnership a step further, voting to create a single transnational union: Nautilus International. In 2015, the United Auto Workers in the U.S. and IG Metall in Germany joined forces to create the Transatlantic Labor Institute focusing on auto worker representation issues at the U.S. plants of German auto manufacturers.(10) In a decade’s span, transnationalism has entered the trade union mainstream as leadership catches up with the objective possibilities opened up by globalization.

Notably, the smartest unions are treating migrant workers not as a threat but as an opportunity. By making common cause with migrant workers, trade unions have deepened their democratic role by integrating migrant workers into unions and combatting divisive and racist political forces. In Singapore and Hong Kong, state-sponsored unions have recruited migrant workers, to mutual benefit. In Malaysia, Building and Woodworkers International, a GUF, recruits temporary migrant workers to work alongside “regular” members of the union. Through such positive, proactive outreach, unions can counter the divide-and-conquer strategy on which anti-union management thrives.

Despite such bright spots, many contradictions and pitfalls impede the forward march of transnational labor organizing. The mismatch between the unlimited scale and complexity of the challenge and the limited resources available remains a chronic problem. Also, successfully organizing new layers of workers may reduce the capacity of unions to take action due to the difficulties of mobilizing an informal or precarious global labor force. These problems are not insurmountable for a nimble and strategic labor movement, but they must be addressed head on.

Reinventing Trade Unions

The persistence of this upsurge in transnational organizing is not inevitable; maintaining growth and success requires deep rethinking of the role of trade unions. To be blunt, the popular image of “pale, male and stale” has an element of truth. Membership is down: no more than seven percent of the world’s labor force belongs to a union, with many of the most unionized sectors of the economy in decline.(11) Many trade unions still take a narrow approach to defending the interests of their existing members, rather than organizing the unorganized, not least those in the informal or precarious sector.(12) And when international trade unions try to create a countervailing force to transnational capital, they often do so in an outdated manner, such as the bid to institutionalize at a global level the postwar European system of tripartite social partnership among workers, employers, and the state.

However, no iron law governs how trade unions respond to crisis. New visions may emerge, new alliances may form, and new forward-thinking leaders may arise. If we see labor as a social movement, we will perceive its constant regeneration. While still weakened by the ravages of the long neoliberal night, the international labor movement has, since the mid-1990s, been regrouping and recomposing. Struggles have matured from desperate rear-guard actions into concerted, proactive organizing campaigns. The International Trade Union Confederation now organizes 207 million workers in 163 countries. The aforementioned GUFs have approximately 200 million members across such key sectors of the global economy as mining, metalwork, transport, steel, building, food, and public services. Together, these global unions show that labor has not disappeared as some had hoped and others had feared. Yet, structures do not in themselves make a social movement, especially when they remain chronically under-resourced.

At the same time, reorganized national trade unions in many countries are becoming significant social and political actors. One promising example can be found in the remarkable recovery of Uganda’s Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union (ATGWU), which, decimated by privatization and anti-union legislation in the 1980s, had shrunk to a mere 2000 members in 2000. By moving into the organization of informal transport workers, with support from the International Transport Workers Federation, membership has grown to over 60,000, and the union has significantly democratized its internal processes. In Indonesia, a seemingly miraculous recovery from the Suharto period (the late 1960s to the late 1990s), when the country’s unions were amongst the weakest in Southeast Asia, has occurred. Since 2000, they have become among the strongest in the region by transforming their repertoire of action: building broad-based coalitions with NGOs, working with informal worker groups, and influencing government policy.(13)

The status of trade union revitalization is subject to debate in both academic and policy circles.(14) Just as types of unions differ, so, too, have their responses to globalization, the closing down of national negotiating space, and the decline in membership. There is no singular path forward. Key directions include recruiting in new areas, with migrant workers an obvious option, building coalitions with other social movements, and intensifying international solidarity actions. Trade unions everywhere (although not all of them) are getting back in touch with their grassroots, improving their communications, and looking outward instead of inward. Trade unions began as part of a popular struggle for democracy, and what the slogans of the French Revolution meant in that day, the principles of the global justice movement could mean today.

The international trade union movement is both a transnational social movement in the making and a representative organization of workers on the ground. Its democratic structures, focus on the world of work, and membership-based nature distinguish it from NGOs campaigning on issues of gender equity, human rights, or environmental protection. While many advocacy groups are ephemeral, the labor movement will almost certainly be around for a long time, since the collective representation of workers is essential even as its organizational form evolves.

That said, the labor movement has learned a lot from social movements and kindred NGOs, and to an increasing degree has been joining the broad alter-globalization movement. The international trade union movement certainly has the motivation to “go global” (even if it is just to survive), and it has the capacity to do so. It can and will play a central and increasing role in achieving a degree of social regulation over the worldwide expansion of capitalism in the decades to come. Indeed, it must.

In the formative stages of the labor movement, unions engaged actively with the broader political issues of the day, in particular, the call for universal suffrage. There is no reason why such larger concerns cannot again move to the center of labor’s agenda, and a very good reason—the interpenetration of a host of economic, social, and environmental reasons—why they should form its backbone. In contrast to the later tradition of craft unionism, the early labor organizers did not recognize divisions based on skill or race. This tradition of labor organizing known variously as community unionism, “deep organizing,” or “social movement unionism” has been making a comeback.(15) Its spread could open a new chapter in labor’s ongoing struggle against capitalism.

Towards a New International

Our world order, globalized from above, cries out for a globalized response from below, a new international fit for the purpose of system transformation in the twenty-first century.16 With their global reach and strategy, trade unions have a central role to play, but labor alone cannot be the international of today. To offer a coherent alternative to the status quo of violence, short-termism, and political chaos, unions must link up with the spectrum of other transnational movements fighting for systemic change on issues from climate change to food security, women’s rights to indigenous rights, and racial justice to income inequality.

What would a new international look like? The models of internationals past are not useful for addressing the complex, interdependent, rapidly changing contemporary world. Nor does the template of the World Social Forum suffice, as it remains trapped by a vision of convening rather than action, and has failed to embrace the major transnational social movements, especially the labor movement.

The labor movement needs to be at the heart of any such effort since the exploitation of labor is as much at the core of capitalist relations of production in the “new” capitalism as in the old. But workers will not be the sole drivers of social transformation. All sorts of divisions—formal and informal workers, male and female, settled and migrants, North and South—must be bridged before labor can realize its full potential in an international fit for twenty-first-century challenges. Many NGOs, philanthropies, and UN organizations have an important role: migrant support groups have brought unions and migrant workers together; women’s groups have brought a feminist perspective to trade unions; environmental groups have helped form incipient green/red alliances. Ultimately, though, only transnationally organized labor can be a counterweight to transnationally organized capital.

The task seems daunting, but the myriad global interactions within and between social movements are already fertilizing the seeds of a new international. While a coordinating mechanism can emerge later, the priority now is to cultivate the basis for joint work and a politics of unity in diversity that engages old and new social movements and operates across spatial scales. This work finds expression around specific issues demanding a global response, such as fighting for climate action, gender equity, organizing the working poor, and alleviating the plight of migrants and refugees.

A new international also needs a shared a vision. Building on existing manifestoes and charters, unions and their allies can foster consensus around a new labor charter comprised of radical reformist measures with transnational resonance.17 Such a charter would be a living document to sustain a virtual dialogue among the sectors of labor, as well as with progressive social movements. Rather than a centralized process, the work can proceed as a web of network interactions—the charter would not gain its legitimacy from the approval of union leadership and intellectual elites, but from union members, shop-floor activists, and allied social movements, all challenging the predations of globalized capitalism.

The charter’s programmatic agenda would evolve to address the concerns of all working people, women and men, urban and rural, high-tech and informal, North and South. A starting list might include the call for a six-hour day to reduce work stress while distributing work more equitably; universal labor rights including the right to strike and engage in international solidarity action; and policies to ease the plight of migrants, the precariat, the self-employed, and the unemployed.

This initial set of demands could then be built on, gathering support from ever-wider sectors and movements, as we work toward an integrated transitional program to take us beyond the current failed social order. Out of this organized effort, complemented by parallel campaigns, would arise the new international we need, where, at its heart, stand the united workers of the world.

Endnotes

- ↩ International Labour Organization, World Employment and Social Outlook 2017: Sustainable Enterprises and Jobs: Formal Enterprises and Decent Work (Geneva: ILO, 2017), ilo.org

- ↩ Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Sandra Tzvetkova, “Working Women: Key Facts and Trends in Female Labor Force Participation,” Our World in Data, October 16, 2017, ourworldindata.org

- ↩“Which Sector Will Create the Most Jobs?”, International Labour Organization, accessed February 1, 2019, ilo.org

- ↩ World Bank, World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2019), worldbank.org

- ↩ Peter Pham, “How Can China Keep up Its Breakneck Economic Pace?” Forbes, March 5, 2018, forbes.com; ILO, World Employment Social Outlook: Trends 2018 (Geneva: ILO, 2018), ilo.org; ILO, Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed. (Geneva: ILO, 2018)

- ↩ Peter Evans, “Is it Labor’s Turn to Globalize?: Twenty-First Century Opportunities and Strategic Responses,” working paper, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, Berkeley, CA, 2010, irle.berkeley.edu

- ↩ Steven Greenhouse, “Pressured, Nike to Help Workers in Honduras,” New York Times, July 26, 2010, nytimes.com

- ↩ Reynald Bourque, “Transnational Trade Unionism and Social Regulation of Globalization,” in Social Innovation, the Social Economy and World Economic Development, eds. Dennis Harrison, György Széll, and Reynald Bourque (New York: Peter Lang, 2009), 123–138

- ↩ Michelle Ford and Michael Gillan, “The Global Union Federations in International Industrial Relations: A Critical Review,” Journal of Industrial Relations 57, no. 3 (2015): 456–475; Peter Evans, “National Labor Movements and Transnational Connections: Global Labor’s Evolving Architecture under Neoliberalism,” working paper, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment, Berkeley, CA, 2014, irle.berkeley.edu; Mariangela Zito, Michela Cirioni, and Claudio Stanzani, Implementation of International Framework Agreements in Multinational Companies (Rome: SindNova, 2015)

- ↩ Steven Greenhouse, “Steelworkers Merge with British Union,” New York Times, July 3, 2008, nytimes.com; “Nautilus Podcast Sheds Light on Union Organising beyond Borders,” press release, Nautilus International, August 29, 2018, nautilusint.org; “UAW, German Auto Worker Union to Announce Joint Efforts,” Automotive News, November 18, 2015, autonews.com

- ↩ See Marcel van der Linden, “The Crisis of World Labor,” Solidarity, 2017, solidarity-us.org

- ↩ For example, the Congress of South African Trade Unions brought together unions and informal worker organizations with its Vulnerable Workers Task Team in 2012, but the effort yielded little in the way of new organizing. See, Pat Horn, “Main Challenges of Organising Vulnerable Workers,” Business Report, March 28, 2014, iol.co.za

- ↩ See Mirko Herberg, ed., Trade Unions in Transformation: Success Stories from all Over the World (Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2018)

- ↩ See Cristian Ibsen and Maite Tapia, “Trade Union Revitalisation: Where Are We Now? Where to Next?”, Journal of Industrial Relations 59, no. 1 (2017): 170–191

- ↩ Jane McAlevey, No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age (London: Verso, 2018)

- ↩ The First International, founded in 1864, engaged diverse political parties, trade unions, cooperatives, and civic associations in Western Europe; the Second International (1889–1916) was based on explicitly social democratic parties (the Socialist International is a contemporary descendant); the Third International (1919–1943) included the communist parties that arose from the Russian Revolution; and the Fourth International formed in 1938 by the followers of Leon Trotsky after his expulsion from the Soviet Union

- ↩ The inspiration here is Peter Waterman, “Needed: A Global Labour Charter Movement,” Interface: A Journal for and about Social Movements 1, no. 2 (2009): 255–262