A lot of companies and entities folded, vanished or ended up in severe trouble in 2008. Bear Sterns, Alfred McAlpine, Virgin Megastores, Merrill Lynch. But perhaps one of the more overlooked and important disestablishments was the Scott Trust.

The Scott Trust was created in 1936 with the objective of “securing the financial position and editorial independence of the Guardian in perpetuity: as a quality national newspaper without party affiliation; remaining faithful to its liberal tradition; as a profit-seeking enterprise managed in an efficient and cost-effective manner.” This trust was dissolved in 2008 and replaced by The Scott Trust Limited, a deceptive name that gives the impression that The Guardian remains controlled by a trust and not a corporation. The change was made in view of “the hypothetical risk of future changes in inheritance tax law that could, in theory, threaten the Guardian’s independence”.

Like all non-charitable trusts, and unlike limited companies, the Scott Trust has a finite lifespan. In light of this, the trustees have decided that pursuance of the core purpose is best served by transferring ownership of the shares they currently hold in GMG to a newly formed, permanent limited company, The Scott Trust Limited. This company becomes the new parent of GMG, replacing the existing trust.

The Scott Trust, 2008

But just how independent exactly is The Guardian as of 2019? the answer perhaps depends on your definition of independence. While no partisan Murdoch style press baron is pushing the buttons and pulling strings, The Guardian is perhaps just as beholden to corporatism and the interests of capital as the next newspaper, regularly espousing the neoliberal “party line” rather the actual views of its left-wing readership.

Let’s take a look at some examples from over the past few days.

Let’s take a look at some examples from over the past few days.

In keeping with a theme that ran throughout much of the press, Labour’s loss of 82 seats at the local elections was considered “heavy losses”. While losses obviously need analysis, describing Labour’s losses as “heavy” in the face of the Tories losing 1333 seats was clearly absurd. The last time a party lost more councillors was in 1995 when John Major lost over two thousand. Yet Labour was the talking point.

And there’s being a talking point and then there’s nothing less than a full broadside on Corbyn. Spreading the debunked  antisemitism conspiracy theory yet further, Jonathan Freedland firmly nailed the Guardian‘s colours to the mast by backing a

antisemitism conspiracy theory yet further, Jonathan Freedland firmly nailed the Guardian‘s colours to the mast by backing a

propaganda campaign that is devised by far-right Israeli nationalists and spread with eagerness by Corbyn’s neoliberal critics.

But The Guardian‘s neoliberal party line doesn’t end with Corbyn, it’s quite happy to ensure that Donald Trump’s imperialist war on Venezuela goes without any possible suggestion it might be anything other than “an uprising” and that the opposition still has “hope” against Maduro.

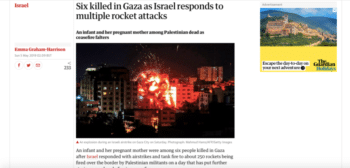

Palestine doesn’t get off scot-free either. While the newspaper rightfully acknowledges that an innocent pregnant woman and child were killed by Israeli violence, they fail to mention that Israel killed two protestors and Injured 82 others including 32 children prior to any suggestion that Hamas fired rockets at Israel. This gives the insidious appearance that Hamas fired first and that Israel can, therefore, be justified in response.

Palestine doesn’t get off scot-free either. While the newspaper rightfully acknowledges that an innocent pregnant woman and child were killed by Israeli violence, they fail to mention that Israel killed two protestors and Injured 82 others including 32 children prior to any suggestion that Hamas fired rockets at Israel. This gives the insidious appearance that Hamas fired first and that Israel can, therefore, be justified in response.

Finally, not quite this week but worth mentioning simply for the ongoing vindictiveness. Here Hadley Freeman spreads debunked conspiracy theories surrounding Julian Assange’s behaviour at the  Ecuadorian embassy that originate with the corrupt Moreno regime. Once again The Guardian would rather stand with Donald Trump than the majority of its readership.

Ecuadorian embassy that originate with the corrupt Moreno regime. Once again The Guardian would rather stand with Donald Trump than the majority of its readership.

The Few, Not The Many

So how have we got to this state of affairs? The best place to start is always at the top and what we find at the top of The Guardian is particularly revealing. For a newspaper that espouses liberal values and is so quick to virtue signal, it is overwhelmingly rich, overwhelmingly middle class and overwhelmingly white.

All information via Bloomberg.

| Board Member | Alma mater | Other Board Memberships/Interests |

| Neil Berkett | Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand | Sage S.A. |

| David Pemsel | Unknown | The Scott Trust Limited |

| Katharine Viner | Pembroke College, Oxford | The Scott Trust Limited |

| Alex Graham | University of Glasgow | The Scott Trust Limited |

| Jennifer Duvalier | University of Oxford | Mitie Group NCC Group |

| Nigel Morris | Unknown | Clownfish Marketing The Advertising Council Aegis Network |

| John Paton | Ryerson University, Canada | Boat International Media ImpreMedia Wanderful Media |

| Baroness Gail Rebuck | Unknown | Penguin Random House Koovs |

| Coram Williams | University of Oxford | Penguin Random House Pearson Publishing |

| Richard Kerr | University of Oxford | None listed |

| Yasmin Jetha | University of London and Imperial College, Cambridge | NatWest Bank Ulster Bank Royal Bank of Scotland |

Some of the annual total compensation figures that we have from Bloomberg across their interests include £1,018,000 for Coram Williams, £706,000 for David Pemsel, £434,000 for Richard Kerr, £372,000 for editor Katherine Viner and £50,000 for Gail Rebuck. Annual compensation is the payment and other expenses for services rendered to employees. The amount of annual compensation is usually between 1.5 and 2 times the annual salary.

What we see here is that the board of The Guardian is made up of those with significant interest in major corporations, at least 5 of the 11 members are Oxbridge educated, likely more. It is made up of those who have come from other major corporations such as the chair Neil Berkett who is formerly of Virgin Media and it is made up of those that are either members of the 1% or represent the interests of the 1%.

These are the few, not the many and the turkey doesn’t vote for Christmas.

But is The Scott Trust Ltd, the owners of the Guardian Media Group, any better?

| Board Member | Alma mater | Other Board Memberships/Interests |

| Alex Graham | University of Glasgow | Guardian Media Group |

| David Pemsel | Unknown | Guardian Media Group |

| Katharine Viner | Pembroke College, Oxford | Guardian Media Group |

| Emily Bell | Christ Church, Oxford | 21st Century Media |

| Catherine Howarth | Unknown | None |

| Will Hutton | Bristol University | Principal of Hertford College, University of Oxford |

| Stuart Proffitt | Unknown | Penguin Press |

| Sir Anthony Salz | Exeter University | The Eden Trust N M Rothschild & Sons |

| Vivian Schiller | Cornell University | None listed |

| Russell Scot | Unknown | The Football League |

| Ole Jacob Sunde | University of Fribourg | Formuesforvaltning AS Blommenholm Industrier AS Schibsted ASA |

| Nils Pratley | Unknown | Guardian Financial Editor |

| David Olusoga | University of Liverpool | None |

While they would certainly appear to be more representative, with less links to Oxbridge and fewer links to corporatism, there are still alarming issues with the makeup of the board alongside indications of exactly where the interests of the newspaper lay. For example, Sir Anthony Salz served as the Head of Independent Review of Business Practices at Barclays, he is Executive Vice Chairman at Rothschild and worked on the merger between Rupert Murdoch’s Sky and British Satellite Broadcasting. Neil Berkett as we mentioned was formerly of Virgin Media.

There are few working-class voices at the top of the Guardian, there are few BAME members. How many of the upper echelons of the newspaper understand the needs of those who require universal credit or even food banks? what can they understand of Venezuela or Palestine? Can they really understand the interests of the ordinary person in the street any more than the likes of The Times or Telegraph?

American Interests

Of particular note is how many of the Scott Trust Ltd have connections to the United States. Vivian Schiller is formerly of CNN, NBC and the NYTimes, Emily Bell is a Professor and Director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York. This sits perfectly with the vision that The Guardian has of its online presence.

The advance of the internet and the world of social media shares has meant that British newspapers have increasingly geared their output toward the United States audience, The Daily Mail is an excellent example of this, having long become a perennial favourite of the far-right MAGA crowd. The Guardian likewise has aimed to generate revenue from the American audience with then Guardian CEO Andrew Miller saying in 2013 that the goal was to “increase the commercial opportunity of our readership.”

I took on the role two years ago and one of the first things I wanted to do was really understand where our readership is to try and see increasing ways of monetising the digital business. It took two seconds to realise that two-thirds of our readers are outside of the UK. And therefore I wanted to try a strategy of modest investment to make sure we increase the commercial opportunity of our readership.

Andrew Miller, 2013

Of course, socialism is not the ideal thing to be promoting to American audiences with Republicans being outright hostile to the prospect and Democrats being at least disinterested, if not equally as hostile. By sticking to the mainstream neoliberal consensus in the United States, having supported Hilary Clinton over Bernie Sanders, for example, The Guardian ensures that it doesn’t rock the boat and continues to keep the revenue flowing. Their positions on Venezuela and Julian Assange fit perfectly in line, not with the British Labour Party and its membership, but the American Democratic Party of Hilary Clinton and Joe Biden.

The majority of that income comes from ad-revenue.

The Bottom Line

In 2013, The Guardian U.S. delivered record online traffic, with 20 million unique users, a 12% growth. Revenues more than doubled in a reflection of advertising demands which included HSBC, Netflix and Airbnb. Of all digital news outlets, HSBC ploughed the most funding into The Guardian.

HSBC has long been criticised for flagrant criminality including money laundering. They currently hold over $1 billion in shares in companies that provide equipment to the Israeli military. In 2014, HSBC closed the accounts of North London Central Mosque and many other Muslim clients as they were used for donating money to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Likewise, Airbnb has regularly come under criticism from the BDS Movement for listing properties in the occupied territories. The Guardian seems quite willing to take their money while telling us how terrible it is.

While perhaps ethically questionable, there’s no reason that the concerns of advertisers should change the editorial policy of The Guardian, is there? not so. In fact, there is evidence that the demands of advertisers have done just that.

While perhaps ethically questionable, there’s no reason that the concerns of advertisers should change the editorial policy of The Guardian, is there? not so. In fact, there is evidence that the demands of advertisers have done just that.

While HSBC was channelling money into The Guardian online, they also had extensive dealings with The Telegraph, a fact that led to the 2015 resignation of Peter Oborne when he revealed that HSBC had unduly influenced his reporting on the aforementioned banning of Muslim accounts at the bank.

Late last year I set to work on a story about the international banking giant HSBC. Well-known British Muslims had received letters out of the blue from HSBC informing them that their accounts had been closed. No reason was given, and it was made plain that there was no possibility of appeal. “It’s like having your water cut off,” one victim told me.

When I submitted it for publication on the Telegraph website, I was at first told there would be no problem. When it was not published I made enquiries. I was fobbed off with excuses, then told there was a legal problem. When I asked the legal department, the lawyers were unaware of any difficulty. When I pushed the point, an executive took me aside and said that “there is a bit of an issue” with HSBC.

Peter Oborne, Open Democracy, 2015

Oborne also revealed just how important online traffic had become to media outlets, being less interested in the factual accuracy of journalism and more interested in exactly how many shares it would receive on social media. Despite their pretence of being aloof to such tactics, The Guardian is by no means different when it comes to the priorities of the modern media.

On 22 September Telegraph online ran a story about a woman with three breasts. One despairing executive told me that it was known this was false even before the story was published. I have no doubt it was published in order to generate online traffic, at which it may have succeeded.

Peter Oborne, Open Democracy, 2015

In 2014, The Guardian inked a “seven-figure” deal with Unilever that was “centred on the shared values of sustainable living and open storytelling”. The move came despite The Guardian‘s public commitment to environmentalism and Unilever being criticised by Greenpeace for causing deforestation through their purchasing of palm oil from suppliers that are doing untold damage to the rainforests of Indonesia. Despite a public commitment to obtaining their palm oil from sustainable sources by 2015, Unilever was criticised in 2016 by Amnesty International when it was revealed their Singapore based palm oil supplier Wilmar International was profiting from child labour and forced labour.

In 2015 The Telegraph revealed that the previous year The Guardian had willingly changed and then removed an article on the Iraq war to avoid upsetting Apple. Apple had purchased significantly expensive “wraparound” advertising on the Guardian‘s website and stipulated that their adverts shouldn’t appear next to “negative news”, a stipulation with an incredibly broad range.

The Guardian has also regularly merged the distinction between what is sponsored advertising and journalism, publishing a variety of articles that have been presented as news or articles when they are paid advertising. The newspaper has also tried its best to hide this fact.

The Guardian has also regularly merged the distinction between what is sponsored advertising and journalism, publishing a variety of articles that have been presented as news or articles when they are paid advertising. The newspaper has also tried its best to hide this fact.

A quick glance at the comments section reveals that the above article once contained the phrase “this content is supported by sponsors” which it no longer does. In 2016 the newspaper began to label sponsored content as “paid content” and appears to have removed all the old references to sponsored content while doing so. Who the sponsors were was seemingly never revealed.

Also in 2016, veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman revealed that The Guardian has published similar sponsored articles in their health care section where the “this content is supported by sponsors” vanished after a number of seconds. Again, no information seems to have been provided as to who was sponsoring the articles or in what form, yet the article contained “quotes from officials representing Pfizer, AstraZeneca, GSK, and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry”.

In 2015, The Guardian had delivered 346 commercial partnerships in the past year including the publication of sponsored content and a project for Sky which “included collating all the articles written across The Guardian to show they were generally more positive than press coverage elsewhere.” Other endeavours included “a roundtable on sustainable diets funded by Tesco and a seminar on public health reform sponsored by drug firm Pfizer.”

The Guardian does not truly represent the interests of either the working class or those suffering under the yoke of American or Israeli imperialism for the simple reasons that others in the press don’t–corporatism and an unrepresentative power structure. The leadership is representative only of middle and upper-class servitude to neoliberal Atlanticism, not to the interests of the struggling working class. The desire to generate revenue, during years of making a loss, has driven the newspaper into the arms of bankers and marketers, creating yet another newspaper unwilling to challenge the political and social status quo for fear of upsetting advertisers or readers and losing that all important revenue. While The Guardian may like to claim it is independent and free thinking, this is either merely wishful thinking or simply a delusion. Or perhaps it’s just a nice slogan to sell to the dreamers, a slogan that they came up with in a marketing meeting one day.

Perhaps, at the end of it all, it really is just all about advertising.