Venezuela in the Centre of the Imperialist Offensive

On 29 April 2019, the attempted military uprising against the government of Nicolás Maduro failed. Two months beforehand, there was an attempt to breach Venezuela’s borders at the Colombian city of Cúcuta under the pretext of delivering humanitarian aid. US President Donald Trump attempted to intensify the economic, financial, and military blockade of both Venezuela and Cuba. The US and UK appropriated Venezuelan assets held outside the country, and Trump openly threatened military action against Venezuela. Meanwhile, the opposition—without popular support—urged protests inside the country and intervention from outside.

Venezuela and its Bolivarian Revolution have been the terrain of a major battle since 1998—when Hugo Chávez won his first election. It intensified after the coup d’état in Honduras in 2009. Harsh US sanctions and threats of war transformed internal disputes in Venezuela into the centrepiece of a global geo-political confrontation. This US-driven policy threatens war and destruction in Latin America.

Open threats of war come alongside a repertoire of tactics used by the US government and its allies to undermine the Venezuelan government and the Bolivarian Revolution. These tactics include a long history of economic pressure that began with the failed coup attempt against the government of Hugo Chávez in 2002 (Stedile, 2019). This is known as a hybrid war—a combination of unconventional and conventional means using a range of state and non-state actors that runs across the spectrum of social and political life (Ceceña, 2012; Borón, 2012; Korybko, 2015).

Korbyko (2015) defines the term hybrid war as:

Externally provoked identity conflicts, which exploit historical, ethnic, religious, socio-economic, and geographic differences within geostrategic transit states through the phased transition from colour revolutions to unconventional wars in order to disrupt, control, or influence multipolar transnational connective infrastructure projects by means of regime tweaking, regime change, or regime reboot.

The methods of intervention are developed in what Korbyko refers to as Full Spectrum Dominance, meaning that they operate with full military and cultural power over various forms of social life, especially over the hearts and minds of the population (Ceceña, 2013; Boron, 2019).

Dossier no. 17 from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research reflects on the hybrid war unleashed against Venezuela. We document the repertoire of tactics, but also the motives behind them. We are interested not only in the recent attack on Venezuela, but in the similarities between this attack and others in Latin America over the past decades. This general onslaught in Latin America needs to be understood not in terms of the war against this country or that one, but in terms of the method of domination that shape the current neo-liberal and imperialist offensive in the region.

El Mango Village in the town of Argelia, Department of Cauca, Colombia. Courtesy of Marcha Patriótica.

The Nature of the Neo-liberal Offensive and Resource Wars Against the Commons

The general economic crisis of 2007-2008 signified the decline of the hegemonic project of the United States of America. A set of so-called emerging countries—especially from East Asia—gradually transformed the axis of capital accumulation. China, in particular, appears to be one country capable of challenging US hegemony through projects such as the ‘New Silk Road’ (Merino and Trivi, 2019), which has been extended from its original Eurasian territorial span into Africa and Latin America.

The United States has reacted to its economic decline in many ways, but one salient approach has been through a new neo-liberal offensive of predatory accumulation and a deepening of finance capital’s hold on the economy. At the centre of this new neo-liberal project is a battle over the control of resources—both goods that had either been held in common or in the public sector and untapped natural resources. Today there is a heightened competition over the control of territories and resources—a competition that has resulted in many belligerent conflicts, from conventional to unconventional wars.

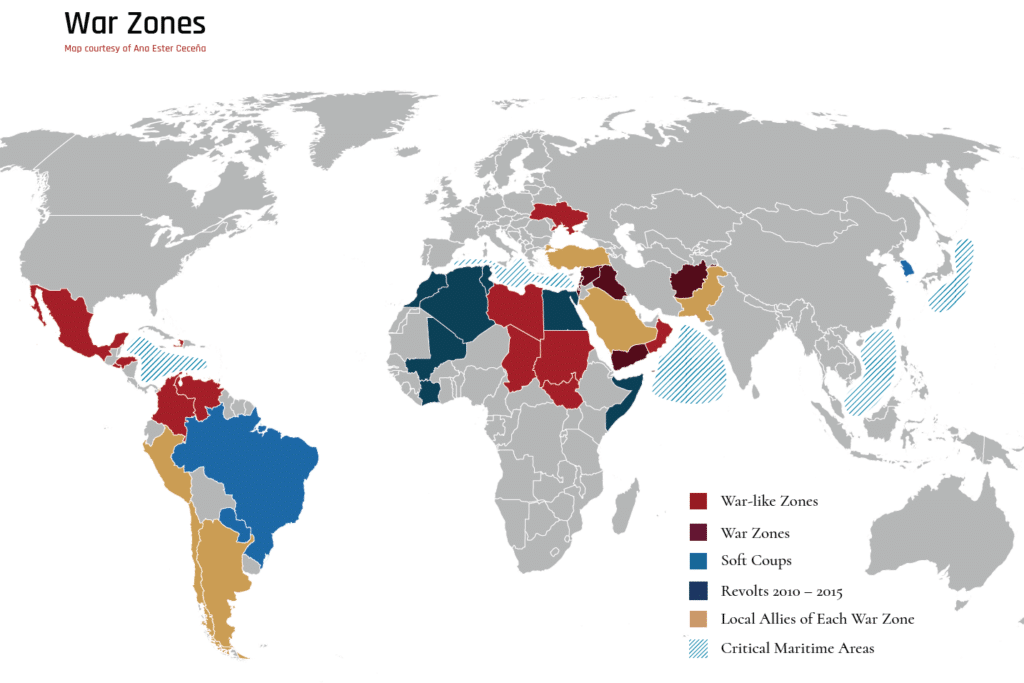

Energy sources, especially oil and natural gas, remain key. Ana Esther Ceceña’s map shows how the areas rich in oil and natural gas are also prone to conflict and war. Thomas Barnett, formerly of the US Naval War College, says that this belt of countries indicates ‘the Pentagon’s primary area of interest.’ A zone rich in energy becomes a zone of war. In these zones, US hegemony is challenged by ‘emerging powers’ such as Russia and China. China’s Belt and Road Initiative, for example, runs through Iran and absorbs North Korea, two countries under US pressure.

The United States considers Latin America to be its ‘natural zone of influence’ and even its ‘backyard’. This is a region rich in natural resources. It is important to list the minerals key to the United States and to US-based corporations: in 2010, Latin America and the Caribbean provided these companies with 93% of its strontium, 66% of its lithium, 59% of its silver, 56% of its rhenium, 54% of its tin and 44% of its aluminium (Bruckmann, 2011). The control of the production of energy—including oil, the control of the extraction of minerals and water, the control of land and biodiversity—offers the United States and foreign capital extraordinary investment opportunities.

To control these natural resources, the United States has used a new strategy—the hybrid war or diffuse war—in addition to conventional wars. The governments that are targeted by the US are those that are hostile to US hegemony. This hybrid war—rather than a conventional war—allows the US to exploit the political, economic and military weakness and limitations of the governments in the region. The goal is to control natural resources as well as markets, transportation lanes and energy systems, and even the lives and imagination of the Latin American population.

The centrepiece of this project is to control the Amazon region, where there is a high concentration of natural resources. The Amazon is a unique region due to its biodiversity. Many communities that live in the Amazon region have—over the years—developed a rich understanding of the plants and animals of the tropical rainforest, knowledge that is coveted by many firms, particularly pharmaceutical companies. Nine South American countries border the Amazon, making it a fulcrum for South American regionalism. Little wonder that it is also central to the project for the assertion of US hegemony in the continent, which now faces a serious assault on its people and resources (see Dossier no. 14: Brazil’s Amazon: The Wealth of the Earth Generates the Poverty of Mankind, 2019).

Part of Venezuela lies in the Amazon region. This is key to the imperialist offensive, particularly because of the region’s immense reserves of hydrocarbons and other minerals. Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves, surpassing Saudi Arabia, although the petroleum is not of the same quality. Even as other sources of energy are being developed, oil continues to be the vital ‘black gold’ that powers capitalist enterprises and the industrialised military. In the short term, the scarcity of oil only exacerbates the dispute for the control of its existing reserves. Due to its geographical proximity to the United States and the potential to save transportation costs, Venezuela is—as the saying goes (with special reference to Mexico)—so far from God, but so close to the United States.

Oil is not the only resource of interest to the United States and Canada (the driving forces in the Lima Group); US and Canadian companies are also very interested in Venezuela’s deposits of gold, nickel, iron and diamonds. Control of Venezuela’s wealth and territory—particularly the Amazon—is crucial to the United States.

The United States began to wage a direct conflict with Venezuela the moment that President Hugo Chávez and the Venezuelan people began to take control of the development of their oil industry and of the country’s other assets—when the wealth of this industry was turned over for national development rather than for corporate profit. In 2002, a US-backed intervention attempted to oust recently elected Chávez from the presidential palace. However, within 48 hours, massive popular uprisings forced the US-backed right to allow Chávez to return. The moment marked not only a break in friendly US-Venezuelan relations, but also a shift in Chávez’s own governance; it was after this that Chávez stepped forward more boldly to strip the Venezuelan elite’s control over the oil industry.

The failed coup d’état in 2002 came as a reaction from the United States and the Venezuelan oligarchy to the new laws of Chávez’s administration regarding hydrocarbons and land. The aftermath of the coup led to the deepening of social control over hydrocarbons, with the transformation of the management of the state oil and gas company PDVSA (Petróleos de Venezuela, SA). For the United States, the objective was to regain control of Venezuela for the production of oil, notably to US firms such as Exxon and Chevron. The ongoing Bolivarian Revolution, however, was intent on using the oil profits from PDVSA for income redistribution through a variety of social programmes.

Part of the US sanctions regime was to deny Venezuela access to the US and global banking systems. To circumvent the US banking system and to carve out a way to sell its oil, Venezuela’s oil company has attempted to trade oil through various crypto-currencies such as the petro, as well as to trade oil with the Venezuelan currency—bolívares. In promoting the use of the petro and the bolívares, the Venezuelan government hoped to be able to circumvent the US embargo on Venezuela and to abandon the use of the dollar for its oil transactions. Venezuela’s moves are not in isolation. Other countries—such as Russia, Iran and China—have also advanced similar procedures. Even the European Union has considered selling gas to Russia in Euros and to create an alternative mechanism to trade Iranian oil.

Venezuela has made progress in diversifying its oil buyers, moving away from its previous reliance upon US oil markets. Since the US embargo has tightened, Venezuela has turned to China—which is now its largest oil purchaser as well as its main creditor. In 2018, Venezuela took out a US$5 billion loan from China. Venezuela has transferred a block of the shares of the oil company CITGO—property of PDVSA—to the Russian energy company Rosneft as a counterpart for another loan. The implications of these deals are important. They show that Venezuela has had to be creative as it meanders around the tight US embargo, which includes an economic and political siege on the country and the appropriation of Venezuela’s foreign holdings. Furthermore, it shows that Venezuela has had to take advantage of newly emerging powers in an increasingly multi-polar world. In this sense, the emergence of China and Russia as alternative trade partners and economics powers is significant.

The Economic War Against the Venezuelan People

If the imperialist bloc does not approve of a government—often for its failure to subordinate itself to imperialism—that government will face severe repression and intervention, often in the form of a hybrid war. The economic battle is a key part of the hybrid war. All methods are used to weaken a country’s economy, rattle its population and then open up society to a ‘guerrilla war’, as Korybko suggests from his reading of the US Army Special Forces’ training documents for unconventional war (Korybko, 2015).

Imperial forces have a long history of intervening to economically suffocate the population of non-aligned countries. Having made them gasp for air, the imperialists blame the governments for—effectively—choking themselves. There is a long chain of such suffocations, with Cuba at the centre. The blockade against Cuba began in October 1960 and was escalated in 1996 with the Helms-Burton law during the Clinton administration. In the 1970s, US President Richard Nixon’s administration made the Chilean economy ‘scream’, which sabotaged the government of Salvador Allende and drove the 1973 coup d’état. In the 1980s and 1990s, the US-dominated finance and development organisations—the IMF and the World Bank—drove policies that created hyperinflation and shortages throughout Latin America; these organisations then presented neo-liberal economic policies that merely heightened the crisis. In other words, the cause of the problem was brought in as its solution. The same policies used against Cuba from 1960 and against Chile from 1971 have been turned against the governments of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro: stingy foreign investment, promotion of capital flight and currency speculation as well as erection of trade barriers that caused planned shortages (CELAG, 2019).

The attempt to suffocate Venezuela intensified in 2012 and deepened in a more belligerent and aggressive manner in 2017. Former chief of the US Southern Command Kurt Tidd laid out the objectives of the economic war in his text, Plan to Overthrow the Venezuelan Dictatorship: ‘Masterstroke’ (23 February 2018).

Increase instability to a critical level by intensifying the undercapitalisation of the country, the leaking out of foreign currency and the deterioration of its monetary base, bringing about the application of new inflationary measures….Fully obstruct imports, and at the same time discouraging potential foreign investors in order to make the situation more critical for the population (Kurt Tidd, US Southern Command, Top Secret/20180223).

We can summarise the multiple tools of imperialism’s economic war in three dimensions (Curcio, 2018).

(1) The production-distribution dimension

Many countries in Latin America—as in the Global South—rely on the export of primary goods for their external revenues. For Venezuela, it is oil. Until the arrival of the Chávez government, the country relied on the import of most food and consumer goods to satisfy the domestic market. Over the past two decades, Venezuela’s government has attempted to increase national production of food. But the progress has been insufficient to meet popular demand. A large percentage of consumer goods and foodstuffs are still imported by the private sector (Vielma, 2018).

The reliance on the export of primary goods and the import of food and consumer goods sets the stage for a particular tactic of the economic war: hyperinflation. The haute-bourgeoisie that controls food imports engineers price increases in two ways: by encouraging shortages of goods and by currency speculation. These two mechanisms are central to manufacturing hyperinflation. Since 2017, average prices have increased by more than 2% daily, spiking in 2018 and at the start of 2019. Researcher Pasqualina Curcio (2018) argues that reliance on food traders who worked with the black market dollar rate (Misión Verdad, 2016) and the withholding of food bought at government-mandated fixed prices created induced shortages and reliance upon black market prices. This resulted in the 90% increase in food prices. These two mechanisms—shortages and currency speculation—erode the economy, setting in motion the contraband and illegal sections, which further promote instability and inflation.

This is why none of the textbook explanations for hyperinflation can be applied to Venezuela. It is not a simple problem of economic mismanagement. The economy has been manipulated to generate discontent, chaos and desperation. Latin America has experienced decades of manipulation of its money supply and goods to create hyperinflation and recession. This is, arguably, a vicious way to discipline the working-class and governments of the people.

(2) The commercial dimension

Dependency on the export of primary goods and the import of food and consumer goods drives countries in Latin America to borrow foreign currency from commercial lenders. This produces a structural vulnerability for countries in the region. Without the free flow of dollars to finance consumption—including of food—society in the region becomes desiccated and the potential of any economic growth withers. To cut off the lending of foreign currency is essentially a death sentence for a country.

No wonder that the United States has issued more than six decrees that punish commercial relations with Venezuela. Fines and sanctions are placed on any firm—commercial and financial—that trades with Venezuela. Commercial cargo, on its way to Venezuela, is routinely confiscated. This is why there is a critical shortage of food, medicine and other basic goods in the country.

Economists Mark Weisbrot and Jeffery Sachs (2019) suggest that these sanctions and this embargo creates a manufactured ‘humanitarian crisis’ that has resulted in the deaths of 40,000 Venezuelans from 2017 to 2018 alone.

(3) The financial dimension

Starting in 2015, with increased intensity since 2017, the United States has impeded Venezuela’s financial operations. Even the normal work of a sovereign state—the issuance of debt and financial instruments to raise funds—has been blocked since these often rely upon financial markets rooted in Wall Street and the City of London. Not only does the US prevent Venezuela from issuing government bonds, but it also prohibits PDVSA from issuing its own financial instruments to raise capital in dollars from different financial markets.

Over the past two years, the US has moved aggressively against Venezuelan assets. It has frozen the funds from CITGO (PDVSA’s company) that operates in the United States. It has encouraged the withholding of gold reserves (valued at US $550 million) deposited in the Bank of England. It has prevented international financial organisations from carrying out any transactions with Venezuela. It has pursued legal action to confiscate public assets of the Venezuelan people. Trump has signed four decrees that stifled the ability of the Venezuelan state to raise funds:

- Executive Order no. 13827 (March 2018) targeted the crypto-currency Petro, which attempted to resolve Venezuela’s exchange rate problem (Teruggi, 2018).

- Executive Order no. 13835 (May 2018) targeted receivable accounts as well as other operations.

- Executive Order no. 13850 (November 2018) prevented the commercialisation of gold.

- Executive Order no. 13857 (January 2019) established a blockade and froze CITGO-PDVSA’s accounts in the United States.

These three dimensions—production, commercial, and financial—produced hyperinflation and scarcity, withdrew the basic tools that the government could have used to solve the crisis, and aggravated the suffering of the Venezuelan people. This is not a normal economic crisis. This is part of a hybrid war strategy deployed by the imperialist bloc. Last year, former US ambassador William Brownfield openly admitted the use of the economic dimension in the hybrid war, saying that ‘perhaps the best solution would be to accelerate the collapse. … we should do it understanding that it’s going to have an impact on millions and millions of people who are already having great difficulty finding enough to eat’. But, he continued, ‘the desired outcome justifies this fairly severe punishment’. Along the same lines, a US State Department spokesperson said at a Mexico City press conference in 2018:

The campaign of pressure against Venezuela is working. The financial sanctions that we have imposed…have forced the government to start falling into default, both in the sovereign debt and in the debt of PDVSA, its oil company. And what we are seeing….is a total economic collapse in Venezuela. Then our policy works, our strategy works, and we will keep it.

Donald Trump imposed new measures against Cuba that are along these same lines, making it relatively impossible for foreign businesses to operate on the island. For example, a new set of sanctions make it possible to prosecute businesses that appear to engage with any part of the economy from which a Cuban-American family had their businesses seized as part of Cuba’s reforms in the years following the revolution

These measures against Cuba and Venezuela are a form of economic and political discipline against all of Latin America. They are a clear message from the US government on what lies ahead for any nation that dares to embark on a radical process of change counter to its imperialist interests.

Violence and the Militarisation of Social Life. The Neoliberalism of War and the Experience of Colombia.

Violence and chaos have struck Venezuela. It begins with small protests and then escalates to road blockages (guarimbas). It morphs into hate crimes and to the incitement to loot. Targeted assassinations follow. The prolonged sabotage of the electricity grid paralyzes the country and poses a serious blow to the government. Each of these acts is designed to incite a reaction from the State and from parastatal groups. This reaction then opens the door to portray the popular government as dictatorial and delegitimise its right to rule.

What we see in Venezuela is something that is commonplace across Latin America today. Imperialism attempts to destabilise institutions and create the conditions for intervention through a coup d’état or by other means. These are direct attacks. But, the structures of neo-liberalism provide other, more covert mechanisms to create social polarisation and crisis. The technologies of economic chaos and the shock tactics to implement IMF policies fragment society. High rates of inequality and the emergence of black markets encourage the growth of mafias, inculcate violence as an economic force, and impose chaos and insecurity amongst the population. It is into this circumstance that we see the emergence of the ‘neo-liberalism of war’, the militarisation of social relationships, and the creation of a punitive security state, that seeks to manage the affairs of an increasingly broken society. A new consensus is bred that is based on the idea of ‘security’ (González Casanova, 2013, Seoane, 2016).

Colombia is a key example of this new consensus. During the government of Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010), the government established an emergency situation—a state of exception—as the normal state of affairs. It was during this government, for instance, that the army assassinated thousands of civilians, who were then falsely passed off as guerrillas to present an image that the army was making an advance against the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), a scandal known as ‘false positives.’

The situation in Colombia is not new. It goes back to the war that began in 1964, although some scholars place its origin even earlier, in the first half of the twentieth century (Moncayo, 2015). In this violent process, a process known as la Violencia (‘the Violence’), a new social class came into being that is made up of a diverse range of social actors—from merchants to landlords to key economic players in the black market. Despite the diversity of its actors, this new social class operates under a united political vision that has very close ties to the United States. This oligarchy’s united political vision is straightforward: to impose neo-liberal economic policies and to adjust ‘democracy’ to enable them to remain in power and rule with an iron fist (Gonzalez Casanova, 2013).

The oligarchy’s bargain is expressed through the militarisation of everyday life, both in the rural and urban areas. According to the Latin American Security and Defence Network (REDSAL), in 2016 there were 1,732,837 troops in the armed forces throughout Latin America—not including the police and private security forces. Brazil has the largest army (366,614), followed by Venezuela (365,315), Mexico (267,656) and then Colombia (265,060). Colombia has the highest proportional number of its armed forces in the army (220,527)—as opposed to the navy and the air force. There is one member of the army for every 220 residents of Colombia (total population of 48 million), while there is only one doctor for every 543 residents of the country (Prada and Salinas, 2016, p. 18). The level of militarisation is more extreme in the periphery of the country, where peasants, indigenous communities and Afro-Colombians are concentrated. Here, landlords and their paramilitaries have waged a systemic war against the population. These landlords—a key part of the oligarchy—fight to expand their control of monoculture farms (including coca), mining, and extensive livestock production (Farjado, 2005). As a result of this war, militarisation is particularly intense at the frontlines of the primitive accumulation of capital. In the region of Catatumbo (population of 288,452)—located in the northern border with Venezuela—there are 9,200 members of the armed forces—not including the police. That means that there is one soldier for every 33 residents. The situation is the same in Arauca and Gujira (which border Venezuela), as well as Cauca, Chocó and Nariño (on the southwest Pacific coast).

The high level of militarisation has not resulted in peace or security for the communities that live there. A study by Indepaz Foundation (2019) finds that the most violent municipalities are in the regions of Catatumbo, Cauca and Arauca, which have the highest concentration of soldiers and which pose the greatest risk to the lives of popular leaders of the peasants, indigenous communities and Afro-Colombians. This is where popular leaders are being assassinated at the highest rates. Between November 2016 to April 2019—since the peace agreement was signed between the Colombian State and the FARC in October 2016—there have been 569 recorded assassinations of leaders of popular movements. 265 of these assassinations—almost half of the total—took place in only 119 of Colombia’s total 1,101 municipalities. The highest number of these murders took place where there was the highest concentration of military troops (Indepaz Foundation, 2019).

The Colombian state did not ask for the demilitarisation of the FARC in order to inaugurate a new age of peace. The oligarchy and the State waged the war to maintain the concentration of their property—including the vast land holdings—and to erase the serious political challenge of the Left (notably the FARC). The peace project suggested neither any compromise on the question of economic inequality nor any compromise on political power.

Rather than advocate for a comprehensive peace project, the government of the United States—led by Donald Trump—has increased its rhetoric around the Drug War, an old argument for US intervention in Colombia. Since the 1990s, the US has used this Drug War argument to station 2,000 marines on Colombia territory to ‘advise’ the Colombian military and to fulfil the US War on Drugs and the Struggle Against Transnational Crime. Needless to say, this is an agenda of the US government and not of the Colombian people, who suffer from this ceaseless war (Vega Cantos, 2015).

Since the 1960s, the conservative government of the Frente Nacional (1962) and the National Police have developed a range of techniques to consolidate the power of the oligarchy (Vargas, 2006). The military and the police have operated together in cities and towns to squash dissent. In recent years, the State has moved into new arenas—notably into cyber-security and psychological operations. Attempts to control society through the manipulation of biometric data (National Police, 2018) have become commonplace. New psychological mechanisms to militarise society have emerged in the past few years (Escobar, 2009). Networks of citizens have been mobilised as a counter-insurgency formation by Álvaro Uribe’s government to both challenge popular struggles by co-opting their adherents and to supplant them by the discourse of security.

The oligarchy—supported by the United States—has succeeded in its project to militarise society and maintain neo-liberal forms of social control. The assassination of social leaders shows both the existence of a limited or restricted democracy as well as the failure of the State to truly suppress social dissent. However, the hybrid war in Colombia has not succeeded in pacifying social and political struggles, which continue to be the primary mechanism by which the people seek change against the establishment. Militarisation keeps the country in the dark, enveloped in a long night that social movements nonetheless illuminate with their struggles and their bravery as they fight for a new dawn in Colombia.

Humanitarian Aid and New Forms of Neo-Colonial Government: The Experience of Haiti

Part of the imperialist strategy regarding Venezuela is to point to the existence of a humanitarian crisis—particularly a crisis of food, medicine and energy—and to then suggest that this crisis is the product of Bolivarian policy. Having made these two claims, an emergency scenario is crafted which is used to justify a foreign intervention masked as humanitarian aid. Comparisons are made between the imperialist attack on Venezuela, the regime change operation in Libya, and the chaos produced in Syria. But little is said of the ‘Haitian model’, which provides an instructive case to better understand what has happened to both the concepts of ‘humanitarian aid’ and ‘multilateral intervention’.

International aid to Haiti has been channelled through about 10,000 non-governmental organisations (NGOs), many of them linked to the European Commission and to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). These NGOs have a budget that is close to Haiti’s GDP and they have more resources than the state agencies for social policy. The result of the growth of the NGO sector in Haiti is that it has fragmented the supply of public services and—as a consequence of the canalisation of funds—has atrophied state institutions. Functions typically assigned to the nation-state are now in the hands of private, transnational actors. The structural problems faced by the Haitian people are not seen in totality but are parcelled out into a microscopic series of problems. The function of the NGO humanitarian sector is to redirect and narrow the anger of the Haitian people from structural issues that uphold the status quo to this problem or that problem, each of which is the remit not of the nation-state or international forces but of this NGO and that NGO.

Portella (2015) notes that NGOs ‘have fed a selfish and mercantile culture with results incapable of promoting structural changes in the country’. This creates a culture of intense competition for resources among the people, with a general attack on the experience of social solidarity. It is worth noting that those who presented themselves as key figures of ‘civil society’—including many NGOs—were key legitimators of the 2004 coup in Haiti.

The problem is not humanitarian aid. It is the selective application of the offer of aid, which masks the manner of imperialist interference. The way ‘humanitarian aid’ works in the logic of imperialism is that it first dehumanises the target country by promoting the view that the people are not capable of helping themselves. It is suggested that this lack of capability to manage even the most elementary aspects of existence is for historical, cultural, political and even racial reasons. This mobilisation of ideology functions to remove the imperialist system from the framework—even though (or even because) it is precisely this system that produces the conditions that demand humanitarian aid. The idea of ‘humanitarian aid’ is a self-fulfilling prophecy that ignores the origin of problems and exaggerates the role of the target countries for the production of distress. The ‘humanitarian aid’ that is offered by the United States and the European Union comes with a halo of legitimacy that is difficult—and yet necessary—to dismantle. This ‘aid’ project is the most sophisticated and effective form of imperialist penetration into the Global South.

The idea of guardianship or trusteeship is essential to understanding the ‘soft’ conceptions of neo-colonial politics. These ‘soft’ tactics of imperialism followed anti-colonial movements that defeated the colonisers through political and military conflicts. Having been removed, the colonisers return through the idea of guardianship or trusteeship under various spurious claims of humanitarianism and of security. Amongst these are humanitarian aid, the war on drugs, technical support to manage unpaid foreign debt, and the prerogatives that come with protection of direct and indirect foreign investment. Alongside these claims is the larger one that the target country is a ‘weak state’, a ‘fragile state’, or a ‘failed state’ (Corten, 2013). These concepts were applied to Somalia, Haiti, and Syria. But there is no such thing as an essentially ‘failed state’. What we have instead are states whose sovereignty has been compromised and whose agenda has been set aside by the intervention of the Washington Consensus. It is imperialism, not ineptitude, that has torn these states apart.

The argument that the humanitarian crisis was created by the ‘failed state’ leads to the conclusion that the ‘international community’ must intervene to preserve ‘international security’. The same script was used against Venezuela. In 2014, US President Barack Obama signed an Executive Order that suggested that the situation in Venezuela posed an ‘unusual and extraordinary’ threat to US national security. Ideas of ‘failed state’ and ‘international community’ were mobilised to threaten an intervention. The Order escalated the economic and military siege of Venezuela, even as the situation on the ground in Venezuela had not changed. Haiti’s crisis was also transformed from an internal problem to an international one. In 2004, the UN Security Council subjected Haiti to Chapter VII of the UN Charter (Resolution 1542), which considers the country a threat to international peace—making the UN Security Council rather than Haitian democracy the arbiter of the country’s future. This situation continues to prevail today. The UN has sent several missions to Haiti based on this mandate, such as the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) from 2004 to 2017—which was made up mostly of Latin American military forces under Brazilian command—and the United Nations Mission to Support Justice in Haiti, from 2017 to the present (Louis-Juste, 2009).

MINUSTAH offers us the example of a ‘proxy’ or ‘subsidiary’ war (Korybko, 2015). It is an outsourced war, with Latin American soldiers in charge of a largely urban population. The mission prepared Latin American military forces for the new national security doctrine—to deal with urban unrest that results from economic inequality and social fragmentation. That the occupation of Haiti was ‘Latin Americanised’ allowed the US and its allies a more economical approach to the exercise of hegemony—and a masked form of domination. The involvement of the Colombian and Brazilian forces in the aggression against Venezuela continues this ‘proxy’ or ‘subsidiary’ war logic.

The entry of forces under the UN flag reduced the sovereignty of Haiti, which lost its ability to control its territory. The coercive function in Haiti was now taken over by a transnational set of actors, who governed the country by remote control through the work of the multilateral military force. On the ground, as society fragmented further, criminal gangs, and drug cartels, NGOs and neo-Pentecostal churches, regional oligarchies and paramilitary forces, international missions and aid agencies tore Haiti into multiple and contested sovereign domains. Haiti’s sovereignty became porous, its ability to control its resources minimal. The fragmentation provided an advantage to the imperialist bloc, which benefits when sovereignty is disrupted and when finance capital is able to move fluidly and without threat to itself. This fragmentation is the character of the neo-colonial form of government.

Virtual Legitimization: The Role of Corporate Media

Out of the ashes of the US defeat in Vietnam (1975) and the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989) arose the US doctrine of ‘full spectrum dominance’. The US government understood that the Vietnamese did not win because of any superior military technology on the part of the guerrilla fighters. Rather, what they had on their side was cultural and moral superiority, which strengthened the resistance of the Vietnamese people and of those who stood in solidarity with them.

‘Full spectrum dominance’, therefore, grasped the importance of the production of subjectivity—the emotions and reactions of people—and the organisation of everyday life. These elements—subjectivity and everyday life—become targets of warfare. The exercise of hegemony is premised upon making one’s worldview the only worldview, to see the world through the eyes of those who exercise hegemony. This worldview not only includes ideological frameworks but also the full range of human emotions—how to understand desire and beauty, values and aesthetics—as well as all the dimensions of human survival—organisation of the market and production. How to feed oneself, how to heal oneself, how to think, how to act—all of this is shaped by one’s conception of reality. If one’s subjectivity and organisation of everyday life is shaped by the hegemonic power, then subordination is near complete—the full spectrum dominance is successful. The war is won before the weapons have been drawn.

Central to ‘full spectrum dominance’ is the emphasis given to the culture industry—not only to the media, but also to the way ‘community’ is shaped. In our world, the organisation of work has mutated into structural unemployment, underemployment and precariousness. In this context, the method for the creation of social interactions has changed. Social subjectivity is formed by new institutions, often fragmentary in their nature—religious sects and sub-cultures as well as the family. Emphasis on these institutions and on the retreat into the family erodes broader platforms of social identity formation—notably through political parties and trade unions, which are not necessarily sectarian.

The media plays a crucial role here. Euclides Mance (2018) observes that there is a three-level network for the flow of information.

1) First, a ‘high command’ which has monopoly control over communication flows—often mass media firms—that deliver information shaped by powerful corporate and political forces.

2) Second, the information is fed into a decentralised network of groups that are divided according to individual preferences and tastes and by geography. These ‘interest groups’ are shaped by computer algorithms that track behaviour and create databases. Mance shows that it is at this level that robots (or bots) operate on the basis of artificial intelligence to both collect data on consumer use and deliver data to deepen social fragmentation.

3) Third, the information that is produced from large firms and channelled through ‘interest groups’ is now distributed from person to person. The channelled information that targets individuals corresponds with his or her interests and desires. This motivates the person to spread this information through his or her social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter). The personal distribution of the information increases its credibility because the individual is known and trusted. This process operates like a virus that infects a system, making it extremely difficult to combat, since eliminating one source—a single person—does not impact the functionality of the system.

In Brazil, for example, this style of information flow was essential to awaken an unengaged middle class, as Pepe Escobar has written (2016). Social media was the mechanism to operate on small groups of young people who then became the spear for the creation of discontent and for the destabilisation of key institutions in the country. It was this process that produced and transmitted the narrative that former presidents Dilma Rousseff and Luiz Lula Inácio da Silva (Lula) are the most corrupt politicians in the country, despite a lack of evidence and despite rife corruption among the right-wing that was left out of the picture, a process discussed in-depth in our fifth dossier:Lula and the Battle for Democracy, June 2018. As we have seen, the extensive use of fake news during the 2018 presidential elections marked the political landscape.

In Venezuela, the media war has reached an extreme level. A diverse array of media institutions participates in the creation of a right-wing common sense about the situation in Venezuela. Traditional large media corporations (print, radio and television) have always been in the hands of, and represented the views of, the wealthy Venezuelan oligarchy. They have used this traditional control to expand into the Internet, where their communication tools have allowed them to dominate the battle of ideas (a concept discussed in-depth in our thirteenth dossier: The New Intellectuals, February 2019). Social media and the use of artificial intelligence allowed the right-wing to assemble, identify, and shape the feelings and desires of sections of the population. This kind of psychological warfare allowed the right-wing to produce the view that the government in Venezuela needs to be overthrown—an operation that is mimicked across Latin America.

Fake news becomes news. False stories about the murder of opposition activists, false economic data, false inflation of crowds at miniscule protests, and false stories about torture form the centrepiece of the misinformation carried out by the big media houses, refracted into social media and into the media of private conversations. Since the middle-class uses social media at higher rates than the working class and the landless poor, it is through this medium that false narratives are transmitted; this is where it becomes ‘real’. These narratives then inform news media outlets when they shape their stories. The working-class and the landless poor do not use these channels in sufficiently large numbers to contest fake news. The wealthy and the middle-class are free to say whatever they want on social media, a relatively class segregated domain. This internal cultural war, fed by right-wing opinion, now feeds the construction of world public opinion through the ‘international’ media.

It is impossible to militarily intervene in a country unless public opinion is disposed to the intervention. Favourable conditions need to be created—especially a scenario that seems to suggest few other alternatives than military intervention. The economic embargo which produces a shortage of goods and the build-up of a military cordon around the country are necessary, but so too are the psychological and communications wars. If world opinion is shaped to see the government as a criminal entity, then war becomes acceptable—perhaps even necessary.

Outside the echo chamber of social media, the realities on the ground in Venezuela are quite different. The world media portrays the Bolivarian government as isolated while it portrays the opposition as having the support of the people. The world media—largely the media of the corporations—develops a narrative of Venezuela that favours the Venezuelan right-wing and imperialist interests. But this narrative does not make sense. It cannot understand why the opposition is unable to overthrow the government. It ignores the mass mobilisations in favour of the government that take place across the country, while it exaggerates the mobilisations for the opposition, even though they are much smaller.

The International Siege and the Threat of Military Intervention

The US government has repeatedly said that ‘all options are on the table’ when it comes to Venezuela. That phrase means simply that the US government is willing to intervene with its military. In early May, opposition leader Juan Guaidó requested that the US Southern Command begin planning for an invasion. There is no question that this is a serious situation.

It is particularly serious because of the long history of US military interventions in Latin America, from the proclamation of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) to the war against Mexico (1846-1848). Few countries in the hemisphere have not been invaded by the US. The list is long: Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, Granada—some of these countries more than once (Suarez Salazar, 2006). However, the US has not yet directly sent its own troops to invade a country in South America. If it does attack Venezuela, it would be its first direct military strike on the continent.

Thus far, it appears as if the US is using the threat of military intervention as part of its diplomatic game as well as to influence events inside Venezuela. Meanwhile, the corporate media is doing its part building a psychosocial operation with few precedents.

El Mango Village in the town of Argelia, Department of Cauca, Colombia. Courtesy of Marcha Patriótica.

Some Latin American and Caribbean countries have agreed to recognise Juan Guaidó, a deputy in the National Assembly, as the interim president. Colombia, Chile, Brazil, and the United States —all led by extreme right-wing governments —have promoted a permanent ‘diplomatic siege’ against the Venezuelan government, which has also found expression in a direct attack on Venezuelan diplomatic property. The US is trying hard to build a regional and international bloc against the Bolivarian government. But this has its limits as there are significant challenges on the international stage. Even the countries that are part of the siege against Venezuela are not keen on direct military action.

A regional war with a multi-national intervention would rely on the participation of neighbouring states such as Colombia, Guyana, and Brazil. But here there are problems. The ruling class in Brazil and its military are not willing to enter such a conflict. They believe that a military intervention has an uncertain outcome, which would not give them significant advantages. The beneficiary will be the United States and international capital, not the Brazilian bourgeoisie. Without Brazil, the possibility of a military option is weakened. A two-front war with the participation of Colombia and Guyana as well as with the Fourth Fleet of the US Southern Command on the Atlantic coast could be possible. Another scenario is for the US to encourage Colombia to invade Venezuela. This option has support from the Colombian government, but it is not operational. The Colombian military has been equipped to fight an unconventional war against a guerrilla army. It is not prepared for a full-scale war against a regular armed force that is highly disciplined and prepared. The only way the Colombian army could prevail is if it acted merely as a deployment platform for an eventual US offensive. Along these lines, joint US-Colombian military exercises have been taking place as have meetings between the Colombian high command and the generals of the US Southern Command.

It is not yet clear what role Venezuela’s neighbouring countries would play in sharing the risk of the outcome of a war on the continent. Direct military intervention in Venezuela would be very costly—with logistical expenses for mobilisation, expenses for the maintenance of troops, expenses for the war and then the casualties. This does not count the political costs to be borne by the region from such a war, which would be devastating.

The US’ recent interventions in Venezuela involve indirect forces, as well as covert operations led by regional powers or secretly financed transnational private contractors. In early May, Reuters reported that a mercenary company—Academi—was prepared to assemble several thousand Latin American military troops to operate in Venezuela. Academi, formerly Blackwater, has a long history of brutality, notably in the US war on Iraq. Towards the end of May, groups of Colombian paramilitaries were captured in Venezuela. They have been accused of preparing acts of violence and destabilisation. Such covert work has been ongoing for the past decade.

Clearly, the Venezuelan government—since the time of Hugo Chávez—has been preparing for the possibility of a direct military intervention. The idea of civil-military unity has been developed into the notion of ‘integral defence’ and into the policy of the Tactical Method of Revolutionary Resistance (Método Táctico de Resistencia Revolucionaria). The entire military structure and its forms of struggle have been reorganised to draw from society’s support of the Bolivarian Revolution (Negrón Varela, 2018). The institutions of popular power—notably the communes—will be key channels of resistance to fight to defend the territory of Venezuela. The construction of popular power in the country is informed by the political will to defend the Bolivarian process.

Dilemmas of the Present and the Future

The assault of the hybrid war against Venezuela has intensified over the past few months. The elements of the hybrid war include: economic and financial suffocation, economic destabilisation, media and diplomatic blockades, the promotion of violence inside the country—including assassinations—the generation of chaos with the attack on essential services (including the electricity grid), the pressure for an institutional fracture or a coup d’état and, finally, the threat of an external military intervention.

We have examined these processes in the preceding pages. We have also looked at how the hybrid war strategy has operated in other countries in the region, notably in Colombia and Haiti. The landscape of the hybrid war shows us how the imperialist offensive has operated throughout the region. Re-colonisation is in the cards, with the project to appropriate the natural resources of the hemisphere. Venezuela is at the centre of this offensive. It is where the Bolivarian experience—which had for a brief time inspired a wave of progressive governments across the hemisphere also known as the Pink Tide—remains alive. That experience is what draws the anger of the imperialist bloc. The attack on Venezuela is not only about the control of natural resources or the control of the Amazon region. It is also about the suppression of an alternative political project that threatens the legitimacy of US hegemony. If Venezuela can succeed in building a sovereign society that benefits the majority of its people, of creating a socialist stronghold in a capitalist world, it calls into question the entire narrative put forth to legitimise the routine theft thrust upon the majority of the world’s population under capitalism, from the appropriation of their labour to the wide-ranging devastation it causes on health, security, and general wellbeing.

In the 1930s, the Peruvian poet César Vallejo wrote a poem for Spain, then in the midst of an ugly civil war. Vallejo reworked the section from the Bible where Jesus tells his apostles to take a chalice of wine, which should now be understood as his blood. Vallejo sang, ‘Spain, take this chalice from me!’ The poem asks children to help Spain, which must not be allowed to fall. Spain in the 1930s is Venezuela today. Latin America must now reject the drums of war.

As we finish writing this text, President Nicolás Maduro remains in dialogue with the so-called International Contact Group. His government has participated in dialogue with the opposition mediated through the government of Norway. He is even willing to call for early parliamentary elections. The US government has deepened the economic blockade by banning all commercial and passenger flights between the US and Venezuela and it has violated the Vienna Convention (when its police entered the Venezuelan embassy in Washington, DC to hand it over to Guaidó’s supporters). There are two sides to this conflict: one side is open to dialogue, while the other is intent on its hybrid war. No-one committed to the values of peace, justice and emancipation can remain indifferent or passive in the face of this conflict.

Authors and Acknowledgements

This dossier was written jointly by the Buenos Aires and São Paulo offices of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. The researchers at the offices worked in collaboration with the Colombian Critical Thinking Group of the Institute of Latin American and Caribbean Studies of the Social Sciences Faculty of the University of Buenos Aires (Grupo de Pensamiento Crítico Colombiano del Instituto de Estudios de América Latina y el Caribe or IEALC), with Lautaro Rivara (a sociologist and militant of the Dessalines Brigade in Haiti), and with Ana Maldonado (a sociologist and militant of the Frente Francisco de Miranda). We are grateful to them and to the researchers whose work—acknowledged in the text—has guided us.

English

- Curcio, Pasqualina. ‘Hyperinflation Is a Powerful Imperialist Weapon’. Monthly Review. Online, 14 May 2009.

- Escobar, Pepe. ‘Brazil, like Russia, Under Attack by Hybrid War’. Counterpunch, 30. March 2016.

- Korybko, Andrew. Hybrid Wars: The Indirect Adaptive Approach to Regime Change, Moscow: Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, 2015.

- Manwaring, Max. Venezuela as an Exporter of 4th Generation Warfare Instability, Carlisle Barracks: US Army War College Press, 2012.

- RESDAL ‘A Comparative Atlas of Defence in Latin America and the Caribbean’. 2016, RESDAL.

- Stedile, Joao Pedro. ‘Notes to discuss the current situation in Venezuela’. La Voie Démocratique, 18 February 2019, latest update, March 18, 2019.

- Suárez, Luis. Century of Terror in Latin America: A Chronicle of U.S. Crimes Against Humanity. Havana: Ocean Press, 2006.

- Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. ‘Dossier 4: The People of Venezuela Go to Vote’. May 2018.

- Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. ‘Dossier 5: Lula and The Battle for Democracy’. June 2018.

- Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research 2018. ‘Dossier 13: The New Intellectual’. February 2019.

- Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. ‘Dossier 14: Brazil’s Amazon: The Wealth of the Earth Generates the Poverty of Humankind’. March 2019.

- Teruggi, Marco. ‘How Do You Prepare a Coup in the 21st Century?’, Internationalist 360°, 16 May 2019.

- Weisbrot, Mark and Sachs, Jeffrey. ‘Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela’, Washington: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April 2019.

Spanish

-

- Boron, Atilio 2019 “Venezuela enfrenta una guerra de quinta generación”, entrevista en Caras y Caretas TV, 10 de mayo.

- Bruckmann, Mónica 2011 Recursos naturales y la geopolítica de la integración sudamericana.

- Ceceña, Ana Esther 2013 “La dominación de espectro completo sobre América”.

- Ceceña, Ana Esther y Barrios Rodriguez, David 2017 “Venezuela ¿invadida o cercada?”. Disponible en.

- Chalmers, Camille 2015 “Haití siempre ha sido un mal ejemplo para determinados intereses”.

- Corten, André (coord.) 2013 Estados débiles: un cuarto de siglo después en Haití y República Dominicana, miradas desde el Siglo XXI (Pétion-Ville: C3 Editions).

- Curcio, Pasqualina 2018 Hiperinflación: arma imperial (Caracas: Editorial Nosotros Mismos)

- Escobar, Felipe y Salamanca, Yesid 2009 “Reseña de ‘De Macondo a Mancuso: Conflicto, violencia política y guerra psicológica en Colombia’ de E. Barrero”.

- Fajardo, Darío 2015 “Estudio sobre los orígenes del conflicto social armado, razones de su persistencia y sus efectos más profundos en la sociedad colombiana”.

- González, Casanova Pablo 2013 “Democracia, neoliberalismo y la lucha por la emancipación”.

- Indepaz 2019. Informe.

- Instituto Tricontinental de Investigación Social 2018 Dossier N° 4. Elecciones presidenciales en Venezuela. ¿Qué es lo que está en juego?

- Instituto Tricontinental de Investigación Social 2019, Dossier N° 14. Amazonía Brasilera: La pobreza de un pueblo como resultado de la riqueza de la tierra.

- Korybko, Andrew 2019 Guerras híbridas. Revoluciones de colores y guerra no convencional (Buenos Aires: Batalla de Ideas).

- Louis-Juste, Jean Anil y otros 2009 Haití: la ocupación militar y la tercerización del imperialismo (Uruguay: Ediciones Universidad Popular Joaquín Lencina).

- Marco Teruggi 2018 “Medidas económicas en la tormenta”.

- Misión Verdad 2016 “Los hilos económicos de la guerra contra Venezuela”.

- Moncayo, Víctor 2015 Hacia la verdad del conflicto: insurgencia guerrillera y orden social vigente. Disponible en.

- Negrón Varela, José 2018 “La razón de porque Estados Unidos no invade Venezuela”.

- Policía Nacional 2018 “Policía Nacional inaugura el Centro de Capacidades para la Ciberseguridad de Colombia ‘C4’”. Disponible en.

- Prada, Sergio y Salinas, Manuel 2016 Estadísticas del sistema de salud: Colombia frente a OCDE (Cali: PROESA—Centro de Estudios en Protección Social y Economía de la Salud)

- Resumen Latinoamericano 2018 “Muy importante: Documento base sobre el Bloqueo económico contra Venezuela”.

- Santiago, Adriana (coord.) 2013 Ayiti pale (Fortaleza: Expressão Gráfica e Editora).

- Seoane, José 2016 “Ofensiva neoliberal y resistencias populares: una contribución al debate colectivo sobre el presente y el futuro de los proyectos emancipatorios en Nuestra América”, en Revista Debates Urgentes N° 4.

- Stedile, Joao Pedro 2019 “Notas para debatir la crisis en Venezuela”.

- Suárez Salazar, Luis 2006 Un siglo de terror en América Latina. Crónica de crímenes de Estados Unidos contra la humanidad (La Habana: Ocean Sur).

- Teruggi, Marco 2018 “Medidas económicas en la tormenta”.

- Teruggi, Marco 2019 “Venezuela ¿cómo se prepara un golpe en el siglo XXI?”, en Revista Cítrica.

- Vargas, Velásquez Alejo 2006 “De una Policía militarizada a una Policía civil: el desafío colombiano en el posconflicto armado”.

- Vega Cantor, Renán 2015 “La dimensión internacional del conflicto social y armado en Colombia injerencia de Los estados Unidos, contrainsurgencia y terrorismo de Estado”.

- Vielma, Franco (2018). “Razones y factores que explican el aumento de los precios en Venezuela”.

- “Cuatro operaciones de propaganda de los halcones sobre Venezuela,” May 14, 2019, Mision Verdad.

Portuguese

- Ceceña, Ana Esther 2019 “Amazônia é fundamental para hegemonia dos EUA na América Latina”. Entrevista realizada pelo Instituto Tricontinental de Pesquisa Social com Ceceña, 5 de maio.

- Escobar, Pepe 2016 O Brasil no epicentro da Guerra Híbrida.

- Mace, Euclides 2018 “As redes de whatsapp como armas de la guerra híbrida na campanha presidencial de Jair Bolsonaro”.

- Portella, Êmily 2015 “O lado oculto da ajuda humanitária: o caso do Haiti”.