‘Fully Automated Luxury Communism’ trivializes the global environmental crisis with badly-researched techno-hype and hopelessly inadequate political plans.

Aaron Bastani

FULLY AUTOMATED LUXURY COMMUNISM

Verso, 2019

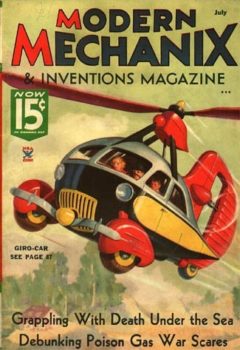

When I was ten years old, I read and re-read a stack of decades-old Modern Mechanix magazines that I found in my grandfather’s basement. Throughout the Great Depression, MM regaled its readers with breathless accounts of technological marvels that were going to change the world, very soon.

Issue after issue promised the kind of things that were later parodied in The Jetsons TV show—flying cars, air conditioned cities, weather control, robots and the like.

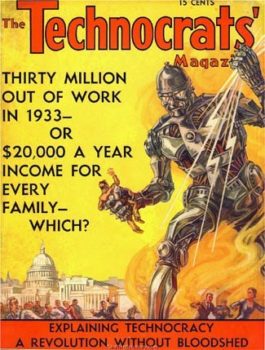

The same publisher produced The Technocrats’ Magazine, devoted to the claim that if engineers ran the government, new technology would lead to a world of plenty and a 13-hour work week.

Fully Automated Luxury Communism lacks the garish covers, but otherwise it reminds me of those magazines. If Aaron Bastani is to be believed, new technological marvels are about to create “a society in which work is eliminated, scarcity replaced by abundance, and where labour and leisure blend into one another.”

The title isn’t a joke—the author, a leftish journalist who often appears on British television, seriously argues that new technology will solve all our problems and usher in a new era of abundance for all, making capitalism obsolete. Agriculture and steam engines radically disrupted human societies in the past, and now a Third Disruption based on information processing and microchips has begun—“a world dramatically different from our own is both inevitable and near at hand.”

Chapter after chapter of Fully Automated Luxury Communism hails the wonderful world of tomorrow. Solar cells will deliver limitless energy so cheaply that fossil fuels will be rapidly and totally replaced. Intelligent robots and automatons will do all the hard work and most of the easy stuff, too. Genetic engineering will “spell the end of age-related and inherited illness altogether.” Milk and eggs and all kinds of meat will be grown in vats, making vegans of us all and eliminating industrial farms. Cheap rockets built by 3-D printers will mine asteroids (“perhaps as early as 2030”) so we will never run out of raw materials.

All of this is related with the kind of gee whiz enthusiasm that ten-year-old me loved in my grandfather’s magazines. Radical changes are coming sooner than we expect, and each is awarded the ultimate futurist accolade—paradigm shift!

In case you doubt that such sweeping changes can happen quickly, Bastani repeats the oft-told story of the “Horse Manure Crisis” that “struck fear into the hearts of Londoners” in 1894. There were so many horses in the city that, The Times calculated, “in fifty years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.” An urban studies conference held four years later found the problem insoluble—but of course it disappeared when automobiles replaced horses a few years later.

Similarly, Bastani tells us,

A few short decades from now, the seemingly terminal problems of today will appear as absurd as the London manure crisis of 1894 does to us.

This was my first clue that Bastani’s research is unreliable, because the Horse Manure Crisis is a myth. The article he confidently quotes was never published in The Times or anywhere else, and that urban studies conference didn’t happen. The Times itself says the story is “fake news.” A simple internet search would have shown him that the anecdote and his conclusion are, well, horse manure.

The rest of his research is just as superficial. He provides no footnotes at all, so his claims are hard to check, but his bibliography mainly lists newspaper and magazine articles, not scientific studies. His enthusiastic account of India’s Green Revolution, for example, depends entirely on one magazine article by anti-environmentalist Gregg Esterbrook, ignoring many studies of the social and environmental damage caused by dependence on proprietary seeds and synthetic fertilizers. His accounts of robots and space mining draw heavily on statements by entrepreneurs whose prime concern is to impress investors. I’m sorry, but Elon Musk is not a reliable guide.

There’s another problem with the horse manure story. While cars solved some problems, they created bigger ones, including air pollution, climate change, urban sprawl, and over a million traffic deaths every year. Not once does Bastani even hint that his exciting new technologies might have downsides. Does engineering the human genome pose no dangers? Will synthetic meat factories have no environmental impact? He tells us that space miners will move mineral-rich asteroids closer to Earth, but doesn’t question the wisdom of pushing gigantic space rocks towards our vulnerable planet. Remember the dinosaurs?

An ecological society will certainly need advanced technologies—but implementing them properly will depend on the precautionary principle, not thoughtless cheerleading.

He doesn’t say so, but Bastani’s argument parallels the claim made by pro-capitalist ecomodernists, that technology will “decouple” economic growth from environmental damage. The difference is that they think capitalism will last forever, while he thinks it can’t survive decoupled growth that radically reduces the cost of energy and goods. “Faced with the limitless, virtually free supply of anything, its internal logic starts to break down. This is because its central presumption is that scarcity will always exist.”

As Bill Jefferies has pointed out, this confuses capitalism as such with neo-classical economic theory. Far from being threatened by abundance, capital thrives on it. If the cost of energy and raw materials falls as Bastani expects, some corporations may disappear, but others will take advantage of low costs to create new industries and manufacture more commodities. Technology may change capitalism, but nothing short of revolution will stop its deadly growth.

Bastani frequently quotes Marx, but his economics are Keynesian, his history is crude technological determinism, and his political program doesn’t go beyond social democratic reforms.

After promising “previously unthinkable abundance” and an end to work, what he actually advocates is an expanded welfare state and traditional electoral politics. Marx said the workers must emancipate themselves, but Bastani tells us that “the majority of people are only able to be politically active for brief periods of time,” so they must depend on populist politicians who will win their votes by promising unlimited luxury for all.

Those politicians will promote local economic development by encouraging cooperatives and credit unions, while central banks keep interest rates low and invest in “automation that serves the people.” Everyone will be guaranteed access to energy, housing, healthcare and education, paid for in part by a tax on greenhouse gas emissions.

Those are progressive measures that deserve support, but none of them goes one step beyond the limits of capitalism. The “transformation as seismic as that of the arrival of agriculture” is nowhere in sight.

Like Modern Mechanix magazines, Bastani’s book is long on sensational speculation, but the back pages don’t deliver on the cover’s promises. It trivializes the global environmental crisis with badly-researched techno-hype and political plans that don’t come close to addressing the world’s problems. In the end, Fully Automated Luxury Communism is just an empty slogan.