Over the past few decades, Indian workers have faced the crushing blows of neo-liberal policy and at the same time fought against them in a spectacular way. Several of the general strikes in the past few years have broken world records–180 million workers on strike in 2016, 200 million this year. Since India won its independence in 1947, it has pursued a ‘mixed’ path of national development. Important sectors of the economy were kept in government hands, while new public-sector firms were established to manufacture essential industrial goods, in line with the country’s development goals. The agricultural sector was also organised so that the government provided credit to farmers at subsidized rates and the government set procurement prices to ensure that farmers continued to grow essential food crops.

All of this changed in 1991 when the government began to ‘liberalize’ the economy, privatise the public sector, reduce its role in the agricultural market and welcome foreign investment. Growth was now premised on the rate of return on financial investment and not on the investment in people and their futures. The new policy orientation–liberalisation–created a new middle class and earned the wealthy fabulous amounts of money. But it has also created an agrarian crisis and produced a precarious situation for workers. The government, since 1991, knew that it was not enough to privatise the public sector and to sell off precious public assets to private hands. It had to do two more things. First, it had to make sure that public sector enterprises would fail and would then lose legitimacy. The government starved these public-sector firms offends and watched them swing in the wind. Without investment, these firms were unable to make improvements and so began to deteriorate. Their demise validated the argument of liberalisation even though their demise had been manufactured by an investment strike. Second, the government pushed to break trade union power by using the courts to undermine the right to strike and by using the legislature to amend trade union laws. Weaker unions would mean demoralized workers, which would mean that workers would now be utterly at the mercy of the private firms.

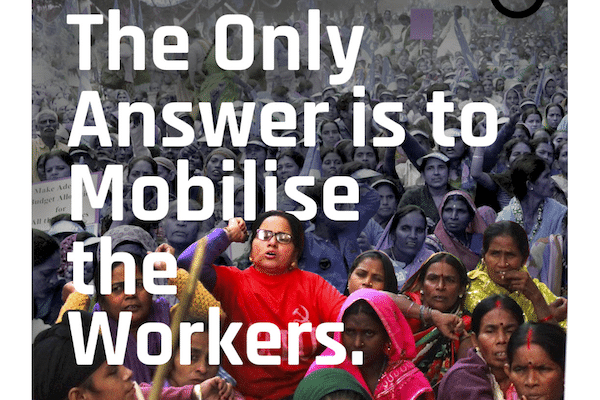

K Hemalata, President of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), addressing the March to Parliament by Child Care Workers organised by the All India Federation of Anganwadi Workers and Helpers (AIFAWH). New Delhi, February 2019.

Photo credits: CITU Archives

However, Indian workers and trade unions have not given up. Ten major worker federations have helped organise seventeen major general strikes over the course of the past fifteen years. One of the key labour federations is the Centre for Indian Trade Unions (CITU), which celebrated its 50th anniversary this year. CITU has a membership of over six million workers. CITU’s president is K. Hemalata, who is also a Central Committee member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and a veteran of the trade union movement in particular as the General Secretary of the All-India Federation of Anganwadi (child care) Workers and Helpers. Hemalata spoke to Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research about the structure of the Indian workforce, about worker militancy and about the challenges before the trade union movement.

In India, a large part of the workforce is in the informal sector. What challenge does this pose to the trade union movement?

The trade union movement globally has been weakened by neo-liberal policies. Trade union rights and trade unions themselves have been under attack. In India, we find that trade unions have not lost our membership. However, only 10% of Indian workers are in the unions affiliated with central trade union federations. According to the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector, about 93% of the Indian workforce is in the unorganized sector with most of them being agricultural workers. We, in the trade union movement, differentiate between the unorganized sector and unorganized workers. Much of the unorganized sector is made up of small firms that employ only one or two workers. But the unorganized workers are not just those who are working in these small firms; they are also workers who are in government employment or employed in large private sector companies who have not yet organised themselves. The increasing tendency by the government as well as large corporations to contractualise and casualise their work force is making the task of unionization very complicated.

None of the governments over the past decades have been able to amend India’s fairly strong labour laws. But they have used different methods to weaken labour rights. The right- wing BJP government has extended fixed-term employment in which workers are given contracts that run for a few weeks; in Haryana, workers are hired for just an hour or two hours on fixed-term contracts. The government notification–because it is constrained by labour laws–says that even fixed-term workers get wages and benefits that are given to permanent workers. But which fixed-term worker–who is employed for a few hours–is going to fight for higher wages or benefits? Fixed-term workers cannot complain or make demands for their rights–not if they want the employer to continue to give them an hour of work here and an hour of work there. The workers are under immense pressure not to demand anything.

But, if workers do not fight, they do not get what is due to them.

The government has provided many a loophole for employers to undermine labour laws. One such loophole is through the schemes for apprenticeships. Workers are not treated as workers but as apprentices who do not earn a wage but only a stipend with no benefits. The National Employability Through Apprenticeship Programme (NETAP) is a joint-venture between the Ministry of Labour and various non-governmental organisations. Agencies that supply workers to employers–such as the Indian online recruitment and job portal Team Lease– are part of this scheme. The agency signs a contract with the firm and supplies workers, who are then moved around between firms. The workers can remain as apprentices for their entire work life. If you are an ‘apprentice’, then you are not a worker. If you are an ‘executive’ or a ‘volunteer’, then too you are not a worker. Workers in sales are now known as executives. Even workers in the National Child Labour Project of the Ministry of Labour are given designations such as ‘volunteer’, ‘friend’, or ‘guest’ so that they are not counted as workers and therefore they cannot be brought under the protections of India’s labour laws.

Importantly, when we go to organise contract workers or ‘apprentices’ or ‘friends’, we find them very receptive to the unions. Some ‘apprentices’ who are hired by the Indian Railways–India’s largest employer–formed an organisation and held a demonstration in Delhi to demand that they be made regular employees. The dichotomy between permanent workers and contract workers needs to be broken down and we need to use our limited resources to organise all workers everywhere.

One of the key elements of the working class today is what is known as precarious work–with the workers known as the precariat, the precarious proletariat. How has the trade union movement tackled the challenges posed by this development?

Our belief is that we must organise the contract workers with the demands of the permanent workers. There should be no difference made between them. If permanent workers’ unions are not convinced that they should include contract workers, we form separate contract worker unions to build their strength. We find that the contract workers are very militant. In the major general strikes of 2015 and 2016, we found that about 40% of those who participated were not in any trade union.

One of the best examples of our work is with regard to theanganwadi (child care centre) workers. In 1989, we initiated contact with the workers of the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) who are otherwise called anganwadi workers. In Andhra Pradesh–where I am from–we went from village to village to locate the anganwadi centres. When we met the workers, they told us that their main grievance was low wages. Moreover, they were considered ‘social workers’ and not workers as such. We found that the women workers faced harassment–even sexual harassment–at work. They were forced to work in the homes of their officers. Their anger at low wages and at harassment made them very militant. We held regular meetings, where the women pushed an agenda to struggle. They were very brave. In the face of retrenchment and of police attacks, they fought on. A lot of political pressure was exerted on these women. But their confidence in the union could not be broken. This has been a very successful struggle amongst the more precarious workers. It helped us sharpen our analysis about the importance of working amongst such workers and about the importance of taking all of their grievances–not only low wages–seriously.

The government now wants to privatise the ICDS, turning over child development schemes to non-governmental organisations and to the private sector. We decided that it is not enough for our union to oppose this privatisation, but that we should mobilize broader village communities against it. The government has basically eroded the ICDS, providing inadequate food for the children and letting the infrastructure– such as the water supply–deteriorate. Anganwadi workers and our union have begun to explain to villagers that the workers want to do their job well, but they cannot do so for lack of resources. Privatisation, instead of solving this problem, is going to make it worse–since now these services will be provided for profit and not for the well-being of the community. We have been mobilizing the beneficiaries of these schemes–entire villages–to go to the Child Development Project offices to demonstrate. The officers had to admit that it is not the fault of the anganwadi workers that the services are not as good as they could be. This admission has given the villagers faith in the anganwadi worker and in the union. It has in fact given the villagers faith in the idea of the union. Construction workers and factory workers in the village now think of unionization as something positive. So, do health care workers, whose militancy is linked to the militancy of anganwadi workers. These campaigns have been contagious.

The anganwadi workers are what we call ‘scheme workers’–they work in various schemes of the government of India. The Child Development Scheme workers are angina workers. The National Health Mission, set up in 2005 by the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, was staffed by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) workers. The anganwadi and ASHA workers are both ‘scheme workers’, as are the midday meal workers (who provide the midday meal for school children) and the Development of Women and Children in Rural Areas (DWCRA) workers.

Workers in each of these schemes suffer from low wages, from being given titles that deny them labour rights (such as ‘helper’ or ‘friend’). We held a massive mobilisation of scheme workers in November 2012 to inform those who work in individual schemes that they are not alone and that they need to unite both on their separate platforms and together around common struggles to fight for their rights.

Take the case of the auxiliary nurse midwives–ANMs. Every primary health centre in villages hires one ANM. Now the government is hiring a second ANM, but under a different name. The second person will be called a ‘social worker’ and paid a lump sum amount instead of a proper wage. Or take the case of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, the elementary education scheme. There are sikshamitras–or ‘guest teachers’–and vidya volunteers who are given a fixed amount instead of wages, and no benefits.

“We want wages, not honorarium for work”. Protesters at the March to Parliament by Child Care Workers under the banner of AIFAWH. New Delhi, February 2019.

Photo credits: CITU Archives

The National Health Mission hires nurses and staff for its hospitals and health centres. The governments of India and Norway have come to an agreement to expand this scheme, but the workers hired as part of the expansion are not treated as full-time workers. They are called yashoda mamata. Yashodais the foster mother of Krishna, a Hindu god. These yashodas who work for the National Health Mission are paid a pittance– 3000 rupees per month. They work around the clock, doing all the work from patient intake to child deliveries to immunization to record keeping. After three years of such work, a yashoda will be replaced by another yashoda. Almost one crore (ten million) workers–mostly women–work in this scheme.

In the government’s agricultural department, there were permanent employees with the title ‘agricultural extension officer’. Now they have been replaced in many parts of India by precarious workers with titles such as adarsha rythu (‘model farmer’) and krishak sathi (‘farmer’s friend’). They are seen as ‘assistants’ and ‘friends’, not as workers. They are given 1500 rupees per month as an honorarium and not as a salary. The same kind of thing has happened to the staff of the National Child Labour Project.

All of these workers–from nurses to midwives to childcare workers–have formed unions. Our task is to consolidate these struggles.

Indian workers are highly mobile, moving from one state to another in search of work. One scholar–Jan Breman–called this phenomenon, which he had studied in Gujarat, footloose labour. The problem with such labour practices is that workers are outside of the social norms with which they are familiar, and they are often attacked as outsiders. How has the trade union movement dealt with this kind of inter-worker pressure, often created by employers for their benefit?

Indian industry has grown along certain industrial belts, such as the Kancheepuram Industrial Area (in Tamil Nadu), the Medak Industrial Area (in Telangana) and the Manesar Industrial Area (in Haryana). Many of these areas have factories of multinational firms such as Foxconn, Honda, Hyundai and Nokia. The factories have some permanent workers, but of course they have even larger numbers of contract workers. Amongst these workers are large numbers of migrants from other parts of India. When workers in these factories go on strike, they are often not supported by the villagers who live near the factories because there are few ties between the workers and the villagers. This was the case in the long struggle by workers in the Maruti Suzuki factory in Manesar. Not only are the workers often from elsewhere, but they also speak different languages than those who live near the factory. There are social fissures that are easily exploited by the employers.

In Himachal Pradesh, the workers’ movement–organised by CITU–is strong in the hydroelectric sector, where a large number of migrants worked during the construction stages of the project. When we began our organisation drive there, we not only worked in the power plants, but, crucially, we also worked amongst the local villagers in coordination with farmers’ unions like the All-India Kisan Sabha (AIKS). This was done not only to form unions of farmers, but also to ensure that the unions of the power plant workers would get support from the villagers.

This was done at a time of great attacks against the workers –including the killing of some of the workers. Our CITU leader from Himachal Pradesh–Rakesh Singha–was attacked and kidnapped in March 2015 during a struggle at the Wangtoo Karcham project of the Jaypee company at Kinnaur.

In Kerala, the Left Democratic Front government has started a programme to offer Malayalam language courses for migrant workers. This allows them to develop closer ties with people who live beside their places of work and in their neighbourhoods. If you provide workers with the means to enter the society where they work, then the divides cannot be so easily exploited by management. We are trying to bring these lessons to bear in other states.

The issue of migration raises the question of where workers are employed. Some workers are employed in Special Economic Zones–as you mentioned–while others are employed at home. Could you talk a little bit about the spatial fragmentation of work and the difficulties this poses in terms of forming unions?

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and Exclusive Export Units are set up all across India, but they are concentrated in a few states. The SEZ Act in India (2005) does not prohibit labour organizing. Formally, all labour laws are applicable to the SEZs, but the government has avoided their implementation in order to attract investments from multinational firms. Labour laws are not honored in these SEZs and workers are afraid. Laws related to maternity benefits, sexual harassment, minimum wage, the right to organisation, collective bargaining, and so on are not applied. Firms are given time-bound exemptions for complying with certain labour laws, say for five years. After five years, they close up their shop, change their name, and start a new factory or they leave one SEZ and go to another.

The firms hire workers from far outside the region of the SEZ. We found that in one SEZ in Andhra Pradesh, the firm employs individual workers from 200 different villages and sends company buses to villages as far as 100 kilometers from the factory. So, these workers are scattered and terrified of losing their jobs. Even then, the workers went on strike and got the factory to agree to improve their working conditions. But the state government used the entire machinery of the state to prevent the agreement from being implemented. The government did not want to provide any example of the advancement of workers’ struggles, since this would perhaps scare off new investment.

Union cadre are not allowed into the SEZs. We wait outside and distribute leaflets based on information provided by disgruntled workers. We share with them an assessment of what they are entitled to based on the law. At the Visakhapatnam Special Economic Zone in Andhra Pradesh, there were Belgian and Israeli-owned diamond cutting factories. Workers at the SEZ went on a spontaneous strike. We supported them. They gained confidence and set up a CITU-affiliated workers’ union. The government refused to accept what had happened. The police were sent in. Earlier the managers used to hire goons to intimidate workers; now the employers seem to hire goons to be the managers.

On one side, you have SEZ workers and on the other you have home-based workers. Home-based production has certainly increased in a range of sectors, from bidi (cigarette) rolling to the stitching of blue jeans. Outsourcing has become rampant. Companies distribute raw material to the workers who manufacture the goods in their homes–often in slums. Workers do not produce the entire product; often they produce just a part of the commodity. This means that the workers are not concentrated in one factory, where they can get organised. Rather, they are working on just a part of the commodity, spatially separated from fellow workers, and have less power because of this. We have taken up the organisation of home- based workers as one of our priorities, but we know that this kind of work is very difficult. In Anantapur (Andhra Pradesh), we have been able to form a union of workers who stitch blue jeans. But it is not strong yet.

One of the methods we are going to use is to organise people in their residential areas and not just at the places of production. We took this decision at the 15th CITU conference in 2016. We decided that workers need to be organised through the struggles for electricity and sanitation as well as ration cards.

Karl Marx, in Capital, wrote that in his time the largest number of workers in Britain were in domestic service. What are the possibilities for organising domestic workers in India?

In general, in most sectors of domestic work, one employer hires several workers. This is the case in a factory or even in-home-based work. But in domestic service, one worker can have many employers. A domestic worker goes from flat to flat cooking and cleaning working for multiple employers in the course of a single day. In this context, it is hard to negotiate with an employer. It is not even always possible to negotiate with a residents’ association for an apartment building. Some unions have been formed in West Bengal, Tripura, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, and Maharashtra. But they are not very strong. That is why we have demanded that the government create welfare boards for those in domestic service. These boards would fix and monitor the provision of minimum wages as well as the working conditions of those in domestic work. But this is not being taken seriously by the government. In Delhi–the capital of India–there are many agencies that supply domestic workers. These agencies are basically labour supply firms. They should be regulated. They often give some modest advance to the workers at high interest rates and then deduct service payments from their wages. Workers get bonded to these agencies. Since we have no strong unions here, we simply cannot do anything. In Kerala too, we are trying to strengthen our union of domestic workers and fight exploitation by agencies.

Women and children at Jamalpur Shekhan village, Haryana. July 2018.

Photo credits: Celina della Croce

What about Information Technology (IT) workers, since they would likely see themselves as white collar professionals rather than as workers?

IT workers began to suffer job loss after the 2008 crisis. The situation in the United States–which was the key destination for Indian IT workers–changed, and U.S. visa possibilities dried up. Before the crisis, workers used to shift jobs easily and they had many opportunities. But the crisis meant that it was difficult to go abroad or to shift jobs or even to earn enough money. Recruitment has come down and pay packages have declined. A feeling grew that they need to organise themselves or at least raise their demands.

At that time, a debate opened up about whether IT workers are workers or professionals. We said that they are workers who have a classical employer-employee relationship and therefore should be organised. Whether they want to form unions or not is a different issue. Whether they have a right to form unions is clear–as employees they certainly have this right. The National Association of Software and Services Companies (NASSCOM) argued that IT employees are professionals and were not therefore workers with a right to unionise. They would, of course, take that position.

IT workers began to hold demonstrations and we supported them. They raised their grievances and they began to organise on the basis of these grievances. Unions began to be formed and registered, such as in Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu.

A sticker, in Tamil language, of the CITU’s Tamil Nadu unit near the venue of the Mazdoor-Kisan Sangharsh Rally (Worker-Peasant Struggle Rally) organised jointly by the CITU, the All India Kisan Sabha (AIKS), and the All India Agricultural Workers Union (AIAWU). New Delhi, September 2018.

Photo credits: Subin Dennis

Out of these struggles we formed the National Coordination Committee of IT and ITeS Employees Unions. In our work, we found that IT eS workers are paid very low salaries–10,000rupees per month–without job security or pensions. They are a highly exploited section of the workforce. This is not just in the private sector. The government has developed an electronic service (‘e-seva’) that digitizes government services in an online portal scheme. The thousands of computer operators that are attached to this scheme are underpaid and exploited. The Coordination Committee works with both private and public-sector IT workers from Odisha to Tamil Nadu, from Telangana to Karnataka. We hope that we will be able to build a movement because the workers feel that they need to be organised. It is possible to organise them. By the way, graphic designers have formed a registered trade union that is affiliated with CITU in Maharashtra. It is a nation-wide union.

One of the elements that plagues the working class is social discrimination. Hierarchies of caste and gender and differences of religion and region play a role in dividing workers. What is the union’s attitude towards social distinctions?

Our union, CITU, turns 50 years old this year. CITU’s first president–BT Ranadive–addressed the issue of social discrimination beginning in the 1970s. But we cannot claim to have addressed this issue forcefully enough. How do you deal with the fact that social hierarchies of caste and gender divide workers? We fight these differences, particularly religious communalism, by linking workers together through their day-to-day issues. The politics of religion and religious fundamentalism divide workers and create conflict amongst them. Such a politics weakens the workers’ movement. We do not oppose religion, but we say it is a personal matter and not something for the union. But, we have come to understand that we have to go deeper. Take the struggles around caste discrimination. It is not something that should be left to oppressed caste or scheduled caste workers to take up alone. The whole union and all workers have to oppose caste discrimination. You cannot unite the working class if you do not consider the divides within the working class. So, unless you take up how the oppressed castes or scheduled castes and scheduled tribes have been deprived and oppressed for centuries, you cannot form strong working-class unity. This has to be explained to the savarna (dominant caste) workers. They have to be convinced of the correctness of the attack against caste hierarchy and they have to be mobilized in a joint struggle. Such a position requires patience. This is the same with gender, an issue that we have tackled since 1979. Organizing working-class women is part of organizing the working class. Platforms might be created to strengthen the confidence of oppressed sections, but the general orientation is to create broad class unity out of this process–not to fragment the working class on the lines of social oppression.

Woman engaged in home-based tailoring work in Bhirdana village, Haryana. July 2018.

Photo credits: Celina della Croce

We have conducted political education around these themes of gender and caste oppression. We have unions that are themselves fragmented by caste, such as safai karamchari (sanitation workers) unions that have historically hired from a certain set of castes and municipal workers who might have come from another set of castes. Both unions are part of our federation, but the connection between them is not strong. We need to take up issues of caste and gender hierarchy not inside individual unions alone but from a political perspective at the level of the federation itself.

What accounts for the militancy of Indian workers overthe past decade? There have been not only large general strikes but also many local struggles.

Militancy has certainly increased and is illustrated by the general strikes–the latest being on 8 and 9 January 2019. Millions of workers joined the struggle. These general strikes brought together almost all of the major labour federations in India, except for the right-wing Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS). The workers and the trade unions had generally formulated demands that came out of their own grievances. Since these general strikes, there is a greater political understanding of the struggle. We moved from five demands to ten, and now to fifteen. These demands have moved from a defense of trade union rights to major reforms to address the agrarian crisis. We have called for a national minimum wage, compulsory recognition of unions and better public distribution of basic commodities. There are also key demands that are specific to the unorganized workers–such as the demand for the abolition of contract labour, the demand for the regularization of scheme workers and the demand for the creation of a social security fund for the unorganized workforce. In March 2019, ten central trade unions created a workers’ charter (see ‘Workers’ Charter of Demands’ in the appendix).

The working class raised these demands based on the entire class, not just on their sector. This is a very positive development.

The cause of this militancy is that the conditions of life have deteriorated for workers in India, both in the countryside and in the city. Wages are stagnant, agriculture is in distress. Struggles in one sector have inspired struggles in another. Farmers who had committed suicide in large numbers as a consequence of the agrarian crisis are now marching on the streets. We saw this in the Kisan (Farmer) Long March in Maharashtra and in the Kisan struggles in Rajasthan and in other parts of central and northern India. We have seen militant struggles of women workers who are in the various schemes. In Andhra Pradesh, when any minister comes to give a speech, the local anganwadi leader is often arrested beforehand or her family members are arrested. As soon as the minister leaves, they are released. This arrest is to stop any protest. In Haryana, the Chief Minister abused women workers because he was afraid of their militancy. He was later forced to apologies due to the women’s actions and mounting public pressure.

Workers have taught each other that struggle is the only way to improve their situation. That is the reason for the wave of militancy.

This militancy has been very impressive, but it has been met by a media blackout and by employer violence. Could you talk about these reactions?

We look at it from a class perspective. The media is controlled by big corporations. They do not want to highlight the hundreds of thousands of workers in demonstrations. If some identity- based organisation or a voluntary organisation does a small protest, they are given a lot of coverage. This is not a question of media management or better public relations. This is a class blackout of our struggles. The neoliberal framework is designed to destroy trade unions. Their silence about us is a form of pretending that we do not exist. We are not surprised by the media blackout. We expect it.

We go directly to the people and explain what the unions are doing, what the workers are doing. The workers and the people must have a close relationship. We have to be our own media. We have been doing this in the case of the anganwadi workers and the transportation workers. When the anganwadi workers go on strike, they explain their actions to the people. When transport workers went on strike, they went to the people and explained how privatisation and the Motor Vehicle Act would dismantle the Public Road Transport Corporations and take benefits away from the people. Electricity workers in Haryana explained that their strike against privatisation was also a strike against the rise in rates for consumers, while the workers in the Federation of Medical and Sales Representatives’ Association of India went to the people to explain that their strike was for health care as a right, to bring the price of medicine down and to improve the entire infrastructure of health care delivery. The people must be involved. This is our approach.

Red Flags at the camping site for participants of the Mazdoor-Kisan Sangharsh Rally (Worker-Peasant Struggle Rally) organised jointly by CITU, AIKS and AIAWU. New Delhi, September 2018.

Photo credits: Subin Dennis

Violence is a normal approach by employers. We say saama daana bheda dandopaya–first you try to bribe the workers, then you threaten them, then you try to divide them and then you kill them. They try all these things. So many of our activists have been beaten, tortured and killed. The capitalists are violent and then they use the courts to accuse workers of violence. The only answer is to mobilize the workers.

Red Flags at the camping site for participants of the Mazdoor-Kisan Sangharsh Rally (Worker-Peasant Struggle Rally) organised jointly by CITU, AIKS and AIAWU. New Delhi, September 2018.

Photo credits: Subin Dennis

Appendix: Workers’ Charter

- Fix the national minimum wage as per the recommendations of the 15th Indian Labour Conference and the Supreme Court judgement in the Raptakos & Brett case, which has been reiterated unanimously by the subsequent 45th and 46th Indian Labour Conferences.

- Abolish the Contract Labour system in jobs of a perennial nature; immediately implement equal wages and benefits to contract workers doing the same job as permanent workers, as per the Supreme Court judgment.

- Stop the outsourcing and contractorisation of jobs of a permanent and perennial nature.

- Strict implementation of equal pay for equal work for men and women as per the Indian Constitution and the EqualRemuneration Act and also as reiterated by the Supreme Court.

- Minimum Support Prices for farmers’ produce as per the recommendations of the Swami Nathan Commission; strengthen the public procurement system.

- Loan waiver to farmers, and institutional credit for small and marginal farmers.

- Comprehensive legislation covering social security and working conditions for all workers, including agricultural workers.

- Take immediate concrete measures to control the skyrocketing prices of essential commodities; ban speculative trading inessential commodities. Expand and strengthen the public distribution system; no compulsory linkage of Aadhar to avail the services of Public Distribution System (PDS).

- Check unemployment through policies encouraging labor-intensive establishments; link financial assistance/incentives/concessions to employers with employment generation in

the concerned establishments; fill up all vacant posts in government departments; lift the ban on recruitment; stop the policy of 3% annual surrender of government posts. - Assure minimum pension of Rs 6000 per month and inflation-indexed pension for all.

- Recognise workers employed in different government schemes, including anganwadi workers and helpers, ASHAs and others employed in the National Health Mission, Mid-Day Meal workers, para-teachers, teaching and non-teaching staff of National Child Labour Projects, Gramin chowkidars, etc. as workers, and pay minimum wages and social security benefits, including pension etc., to all of them.

- Immediately revoke ‘Fixed Term Employment’, which is in violation of the spirit of ILO Recommendation 204 that India has ratified.

- Stop the disinvestment/strategic sale of public sector undertakings. Give revival packages to important Public-Sector Undertakings (PSU) in the public interest.

- Revival and opening of sick jute industries and tea plantations, as thousands of workers in these industries are facing distress, malnutrition and deaths due to closure.

- Revoke the decision to privatise railways, defense, ports and docks, banks, insurance, coal, etc. Immediately revoke the decision allowing commercial mining of coal.

- Stop privatizing defense production and closure of defense units. Strengthen and expand the state-owned defense industry to achieve self-reliance in defense.

- Stringent measures to recover bad loans in banks; take criminal action against deliberate corporate defaulters. Do not pass on the burden of bad loans onto the banking public through penalties and higher service charges. Stop the merger and amalgamation of public sector banks. Stop the closure of bank branches. Increase the interest rate on bank deposits to offset the inflation rate.

- Periodic wage revision to all CPSU Workers without insisting on any affordability condition.

- Withdraw the Motor Vehicle Act (Amendment) Bill 2017, and Electricity (Amendment) Bill, 2018.

- Immediately resolve the issues of central government employees related to the recommendations of the 7th Pay Commission.

- Scrap the New Pension Scheme and restore the Old Pension Scheme.

- Stop anti-worker and pro-employer amendments to labourlaws and codifications. Ensure strict implementation of existing labour laws.

- Implement paid maternity leave of 26 weeks, maternity benefit and crèche facilities for women workers; no incentive should be given to employers who are following amended provision of Maternity Benefit Act as proposed by the Government.

- Strict implementation of the Prevention of Sexual

Harassment of Women at Workplace Act. To increase political participation, immediately enact 33% reservation for women in state legislatures and Parliament. - Ratify ILO Conventions 87 and 98 on the Freedom of Association and the Right to Collective Bargaining along with the ILO Convention 189 on Domestic Workers.

- Stop the dilution of OSH & Welfare provisions through the merger of 13 Acts in one Code. Ensure the implementation of existing Acts and rules. Fill vacant posts of factory inspectors, mine inspectors, etc.; lift the ban on inspections. Ratify ILO C-155 and recommendation 164 related to OSH &Environment. Tripartite audit of human and financial loss due to accidents should be mandatory.

- Strengthen Bipartism and Tripartism; make recognition of trade unions by employer’s mandatory in every establishment; no decision should be taken on any issue related to labour without consensus through discussion with trade unions; ensure regular, meaningful social dialogue with workers’ representatives.

- Cut the subsidies given to corporates.

- Make the Right to Work a fundamental right by amending the Constitution.

- Ensure 300 days of work under MGNREGA. Enact similar legislation to cover urban areas. Fix minimum wages to not be less than the minimum wage of the respective state.

- Strict measures to stop the inhuman practice of manual scavenging. Compensation, as per Supreme Court judgment, to the families who die while cleaning sewers.

- Strict implementation of the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act.

- Immediately fill up all backlogs in the posts reserved for SC/ST; reservation of jobs for SC/ST in private sector employment.

- No eviction of Adivasis from their habitats, strict implementation of the Forest Rights Act for Adivasis.

- Protect couples opting for inter-caste and inter-religious marriages. Ensure strict actions against those encouraging/resorting to so-called ‘honour killings’.

- Ensure strict punishment for all those who are guilty of rape and other cases of violence against women. Make such offences ‘rarest of the rare’, with capital punishment to ensure safety of women in letter and spirit.

- Ensure effective implementation of Article 51 A of the Constitution that calls upon all citizens to promote harmony, spirit of common brotherhood, diversities and to transcend religious, linguistic, regional and sectional culture and to denounce policies derogatory to the dignity of women.

- Free and compulsory education for all children up to ClassXII along with technical education. The budget allocation for education should be 10% of the GDP.

- Free health care for all. Strengthen health infrastructure, particularly in the rural and tribal areas. Increase government expenditure on health to 5% of the GDP.

- Potable drinking water should be provided to the whole populace.

- Protection of street vendors should be ensured. States should frame rules accordingly.

- In order to protect the interests of home-based workers, which is a women-dominated sector, ILO Convention 177 on Home Work should be ratified along with an Act for Home-Based Workers.

- Workers should have active and effective participation

in all welfare boards constituted for their welfare. The unspent amount of cess collected under Building and Other Construction Workers’ Welfare Board should be spent only on welfare of workers. Welfare boards should have adequate workers’ representation. The functioning of the boards should be strengthened so that workers can get registered with the board and have easy access to welfare benefits. - The Government should direct States to frame the rules forth inclusion of waste recyclers of solid waste management in cities at all levels.

- The Working Journalists Act should be amended to include journalists and workers from all media organisations to ensure decent wages and job security. Constitute a new wage board for journalists in print, electronic and digital media to revise wages in media organisations.