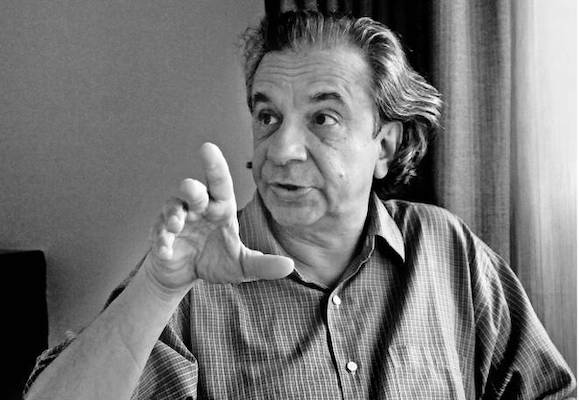

Interview with Akeel Bilgrami. This is the final part of a two-part article.

YOU have pointed out the role of liberalism in keeping out the New Deal and the social democratic ideals of [Bernie] Sanders and [Jeremy] Corbyn. And you were highly critical of liberalism for that reason. You also said that liberalism is ensuring that nothing in the political arena is conceptually available for a fundamental transformation of society. But you are not equating social democracy with a fundamental transformation of society, are you? We know, from your writings, that you believe that social democracy does not amount to a radical critique of capitalism. So, then, can you explain what you have in mind exactly?

That raises a whole range of very familiar and long-standing issues that have afflicted the Left, leading to debates in India (and no doubt in other places as well) between the organised Left and what has come to be called the “ultra-Left” and the insurgent Left.

I think that what is true and what everybody knows is that liberalism in the 20th century has, as I’ve put it in some of my writing, “taken social democracy in its stride”, that is, taken in its stride the social-democratic constraints that had been put on capitalism after the end of the Second World War. But the point of the expression “take in its stride” should not be seen as merely saying that liberalism is able to accommodate these constraints in its doctrinal framework because they don’t constitute a fundamental critique of capitalism. What more is connoted by “take in its stride” is very important, in fact absolutely crucial, in understanding capitalism today and the ideological role of liberalism and the exact nature of the accommodation.

So, what would be this “more” you would add to the nature of the accommodation?

It is this. Liberalism takes social democracy in its stride not only by accommodating social democracy but also by making sure that the accommodation is always constantly being undermined, even as it is allowed to be there. In other words, social democracy should not be allowed an equilibrium (leave alone strengthening) within its accommodated status. That is the point of liberalism and it recurs everywhere. Even the Scandinavian countries are subject to it, though, of course, being more peripheral than the main belt of capitalism, social democracy there has not been so recurrently subject to this disequilibrium and instability in its status as in other parts of the capitalist world. So, when one says liberalism accommodates social democracy, we must be absolutely clear that that accommodation is never stable and is never going to be allowed to be stable.

Though he does not speak of the crucial role of liberalism in maintaining this constant undermining pressure and disequilibrium, Prabhat Patnaik has made a related point about capitalism today in a very sharp and illuminating way. What he has said is that “the spontaneous tendencies of capitalism” simply do not allow constraints upon capital to be permanent. I am really relying on that fundamental point he makes. I’m taking it for granted.

It is worth getting clear about what exactly he means. Here is what I think he has in mind by this rather deep theoretical point in his analysis of capitalism.

The word “spontaneous” to describe these tendencies, an expression that Patnaik takes from [the Polish economist] Oskar Lange, is a little startling here because it is standardly used by philosophers (Immanuel Kant, for instance) to be synonymous with “freedom”, whereas Patnaik is talking about the opposite of freedom, the deterministic tendencies of capital. But it is not that hard to sort out what is going on. What he means is that our freedom to put abiding constraints on capital does not exist because capitalism is a deterministic force. Or to put it differently, in a way that explains why they are called the “spontaneous” tendencies of capital: in capitalism, the only thing that possesses freedom or spontaneity is capital. We don’t possess the freedom to constrain capital (at least not permanently). It is in the nature of these tendencies, and therefore in the nature of capital, to refuse to tolerate more than temporary constraints upon itself. And, if this is right, I am saying that what we are seeing today is liberalism’s essential role in facilitating these tendencies. All this has interesting consequences for how to think about the standard debates that I mentioned earlier.

Another way to elaborate Patnaik’s point is in terms of a disjunction. As he says, what follows from this point about the tendencies of capitalism to eventually undermine constraints on it, is that EITHER you transcend capitalism OR capitalism will undermine you (that is, undermine the constraints you bring to it, to capital). So, we, as human subjects in the modern period with its unique economic formation, are determined in the sense that we cannot constrain that formation, but we are also free, free to transcend the formation. That is where our freedom lies. It does not lie in establishing a stable, permanent, set of social-democratic constraints on capital since the deterministic tendencies of capital will never permit such constraints anything more than a temporary status.

The relevance of this to the debates I mentioned is that there is a position (call it ultra-Left if you like, I don’t care about labels, perhaps real world ultra-leftists will reject what I am attributing to them) which says the following: Because capitalism so completely dominates the political arena and its institutions, including parliamentary politics, the latter must be held in suspicion; what is to be sought is to overcome and transcend capital by some other, perhaps more direct, means. And I think the other position (call it the position of the organised Left, again labels are neither here nor there) is to say that the political path to transcendence comes from first establishing social democratic constraints via parliamentary politics (under the full awareness that there will be no stable accommodation of them within capitalism and the liberal ideologies that prop it up) and then proceed to build on these constraints so as to eventually transcend capital. This is not the place to discuss these options in detail.

What I really meant to stress is that contemporary populism surfaces everywhere today because ordinary working people have not been allowed by the twin causal conditions I outlined earlier to even so much as configure conceptually what such a transcendence would mean, leave alone to see their way to a path to politically achieve it.

Can you give a more concrete example to explain what you have in mind when you talk of “meaning” here and your references earlier to how ordinary people do not even have available in their political zeitgeist the “conceptual vocabulary” to make a radical critique of capitalism and seek thereby a path to overcoming and transcending it? How does this lack have specific or concrete consequences? Can you explain?

Yes, sure. Let’s look at the first failure of inference, the one I attributed to ordinary working people who have a sound scepticism about globalisation and the supra-nation of Europe but who draw the wrong inference from it when they express their xenophobic opposition to immigration.

The point here is that within a certain framework of thinking (the one, for example, shared by a liberal consensus between Blairite Labour thinking and Tory thinking which dominated British political culture through the neoliberal period; actually Labour thinking on this goes back further, if you recall the early [James] Callaghan talk of austerity), there are no conceptual resources available by which you could actually establish that immigration could be an asset for the economy. To get to that alternative framework of thought whereby you could establish that, you’d have to push in a certain direction the scepticism about globalisation and Europe that is expressed in the populist’s sound premise, but people just don’t have the conceptual resources to push in that direction. It’s just simply not among the options that are conceptualised in the politics frameworked by the liberal consensus. That’s what makes liberalism the deepest enemy of a genuine Left. Marx saw this in the celebrated essay “On the Jewish Question”, and we have talked about this more philosophically in an earlier interview.

You know, conservatism is an easy target. When I say that, I am not denying that conservatism (whether it is the Tories or the Republicans in the two countries we have focussed on in the discussion) is very often the more immediate danger, nor am I denying that wherever it wins elections, life gets harder for working people. But speaking more theoretically, the eventual obstacles are the role played by liberalism in making sure that Conservatives are the only alternative to a Blairite Labour or Clintonite Democratic position. And not only must it, for this reason, be the eventual target for a genuinely radical position, but it is also the more difficult target because liberalism always claims the moral high ground by opposing the unsavoury populisms of the extreme Right (while, of course, at the same time constantly sneering at Sanders and Corbyn as unelectable “populisms” too). Thus, my point is that they have no right to blame the xenophobia because they are partly responsible for there not being conceptually available to working people any resources to construct upon their instinctively insightful scepticism about globalisation and Europe, an alternative framework within which they could have a different view of immigration. It is this that lies behind the point I was making earlier that you can’t blame people for something that the cognitive resources are not there for them in the political options that have been conceptualised. It is undemocratic to blame them. We should be blaming those who are responsible for that cognitive deficit in the political culture. And that is what I hold liberalism responsible for and that is why I think that they are, in the end, the deepest enemy.

All this is really just bringing out in more concrete terms by a discussion of Brexit in particular, what I was saying in a much more philosophical vein in an earlier interview with you while discussing Marx’s essay on the Jewish question and [Mahatma] Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj. And you know this is echoed everywhere in our culture, not just in the political arena but in the academy as well.

Take economics departments in virtually any university in the United States, which is where I know universities best. Suppose by some miracle a radical socialist economist got tenure in an economics department at a standard university in America. The liberal consensus in the discipline would completely marginalise her. It’s not as if they would censor her or dictate to her what she can or cannot say or write (oh no, that would mean liberalism would lose its moral high ground). No, they would just make her irrelevant with pity: “Poor thing, she is 50 years out of date.” And in that ethos, most people, out of careerist anxiety, just adjust and shed their radically alternative conceptual frameworks in the discipline. If this happens pervasively in universities where capital has much less direct influence, you can imagine how much more it happens in the journalistic arena and, of course, in the political arena, which is what we have been discussing in this elaboration of the causal conditions that give rise to contemporary populisms.

So, what would you say is the solution? You say it is hard to envisage the end of capitalism, and you have shown sympathy for the instinctive scepticism about globalisation on the part of populism, despite people drawing wrong inferences from it, so would you agree with Samir Amin and Prabhat Patnaik that there should be a delinking of nations from globalisation, whether it be Brexit-like departures from Europe or more generally from the global economy that comprises contemporary neoliberal capitalism?

That is a very large question. And there should be much more discussion of it than there has hitherto been. It does seem as if something like that is inevitably going to be required as an initial step in the resistance to the ill effects of capitalism we have been discussing. But it is interesting that both the Marxist theorists you mention who have proposed this are from the South. It is just not on the horizon of Left thinking in Europe, at any rate any thinking that has any actual influence in politics. This is evident even in [Yanis] Varoufakis’ pronouncements and writings, despite his walking out of the Greek left-wing government. He will simply not countenance full national sovereignty over one’s own economy even as he rails against the establishment in Brussels and Frankfurt.

However, I do think it is just possible that Corbyn is a closet Brexiteer unable to name his position openly. The situation is extremely difficult for him for obvious reasons. There is going to be a lot of hardship that people will initially face in the short run if there is delinking, wherever it may be; any government which leads such a move will have huge problems to cope with and will have to work very hard at public education of the country’s population to present a long-term (and midterm) programme that carries conviction.

There will be a great temptation to resort to the path of austerity again, which must be resisted. There will have to be a fearless resolve to tax wealth and to tax the corporations to generate the revenues needed to avoid taking that path. In fact, something like this was the resolve in that leaked Corbyn Labour manifesto that fetched him such notoriety. All the man and the Momentum group in the party behind him was trying to propose for the post-Brexit period was to make electoral politics about something other than immigration and all it got him was notoriety, spearheaded by the sneering once again by the liberal pundits in the mainstream press, though it did consolidate his popularity among his own base. An alternative model of growth implemented through the exercise of national sovereignty over one’s own economy would have to not only be devised but made part of the agenda for educating the national public to accept it after years of having been brainwashed by propaganda (still zestfully pursued by a liberal consensus between the Tories and Blairite Labour) about the only path to growth being globalisation. Working-class’ instinctive anti-globalisation stance will not suffice. If a humane politics and political economy is sought over the middle and long run, that instinctive perceptiveness will have to be given a framework that provides an alternative form of thinking about the fundamental issues of political economy, and the concepts on which that thinking is constructed will have to become a familiar part of the political culture and zeitgeist through public education into the concepts.

As for countries of the South, were there to be delinking to regain national sovereignty over one’s economy, I think there is a simple thought experiment that economists should debate about by asking a question in the subjunctive: Would such a delinking have the effect of making the countries of the South better off than they have hitherto been and the countries of the North worse off? These things need to be debated by economists. I realise that “better off and worse off” are often themselves ideologically constituted measures, but assuming one can get over those ideological filters to agree on a neutral understanding of those terms, it would be a worthwhile debate to have among economists.

In fact, if you read the exchange between David Harvey and the Patnaiks over imperialism in the new book by the Patnaiks on the subject [A Theory of Imperialism by Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik, November 2016], this debate has already begun in a preliminary way. It needs to be pursued further. But it is very interesting to me that the only economists to be taking this line of delinking are from the South. It just shows how far globalisation has gone into shaping the thinking of even Marxist economists in the North.

If even Marxists economists of the North are opposed to delinking, it is hardly surprising that [Francis] Fukuyama summarised a whole range of Northern thinking about the current period’s political economy as constituting the “end of history”. He is just saying what I cited earlier from Frederic Jameson but with the attitude of applauding it, while Jameson was lamenting it. (Actually, in this they were both—in a remote but not by any means fanciful way—anticipated, with neither applause nor lament, in a clinically brilliant reading of Hegel by [Alexandre] Kojeve in lectures that were very influential in the European philosophy of the last century.)

I should make clear, what should be obvious anyway, that I am not equating Left theorists and economists in Europe with Fukuyama. Not at all. I am only saying that except for a very few economists in the South there is a pervasive embrace of the inevitability of globalisation and some vague, mostly unelaborated, hunch that a radical Left transformation is possible within globalisation—captured in some slogans of eminent Left economists such as: “Making globalisation work”. In a recent article in New Left Review, analysing [Donald] Trump’s America, Perry Anderson says in passing that the Left should be seeking a “genuinely alternative international platform”. He does not say a word to elaborate on it. I have no idea what he has in mind.

Mind you, it is not as if delinking for countries of the South would not come with problems of its own. The smaller economies will be at a disadvantage compared with the large countries with diverse natural resources, and so there would have to be South-South links that would have to be formed to protect the smaller nations. This would be a quite different form of relinking than BRICS [Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa]. And there is another kind of problem that often comes up in discussions these days regarding these issues. There is beginning to be a tendency to say that since countries like China (and even India to some extent) are making their economic presence felt in Africa and Latin America, there are new imperialisms emerging, and my thought-experimental question is not power centres and so it cannot just be a matter of the North’s domination over the South. Well, maybe.

But I think those are only complicating factors. I think we can count those factors in and hold those variables steady and still pose my thought-experimental question for economists to discuss, and if the outcome of this discussion is that indeed the South will be better off and the North worse off, it will bring out the extent to which economic imperialism by the advanced capitalist nations of the North over Southern nations has continued to exist since the political decolonisation that took place roughly the middle of the last century and especially accelerated via financial globalisation from the 1980s on. And that will obviously make a strong case for countries of the South to delink from global finance.

Will it not be very hard for the Left in countries of the South to get their governments to embrace delinking policies, given the fact that these governments are dominated by the corporate elites in their own countries?

Scope for resistance

You are certainly right about it being very hard these days. Left movements within nations are very weak for reasons widely known, having to do with how neoliberalism has steadily undermined the bargaining power of labour in the last quarter century both in India and everywhere else. This is, of course, partly due to the creation of a form of employment that is impermanent and part-time and contractualised. And there is also the standard “reserve army” effect that allows employers to squash the bargaining power of employed labour. In fact, the two are linked since the reserve army effect is partly to create that kind of casual form of employment. All this is undeniable. The task is deeply uphill.

But what is the alternative? Just consider, by contrast, what resistance there would be at the international level? What does it even mean? Ever since the Bretton Woods institutions were remantled, we have witnessed a kind of unleashing of capital mobility that has, as we have been saying, deprived nation states of sovereignty over their own economies because of anxieties about capital flight. But its effect on movements of resistance is equally alarming. So, take, for instance, [Luiz Inacio] Lula [da Silva]’s initial success in coming to power [in Brazil]. He came to power on the wave of a tremendous working-class movement with an impressively progressive manifesto. But how much could he do, how much could he implement given the fear of capital flight while the economy is linked to global finance? Given the link, it would have been irresponsible to implement it since capital flight would have, among other things, resulted in massive unemployment.

And so, if there is to be effectiveness of resistance under globalisation, there would have to be movements waiting at whichever place capital flies to. What sort of international solidarities would that require? Can we even imagine such a thing? [Michael] Hardt and [Antonio] Negri talk of “multitude” as a kind of “de-territorialised” resistance. Have they or anyone else ever made clear what that is apart from a fantasy? Even just within Europe, Podemos failed to come through with any support of Greece during its recent trials with the European banking establishment.

So, difficult as it is, there is only real scope for resistance at the national level. In Left commentary in India on the large September 5 [2018] worker-peasant (including agricultural labourers) rally, it was pointed out how significant it was that solidarity was shown between these two groups despite distinct and conflicting interests (after all, peasants want higher prices for what they produce, but that hurts the worker in the city who purchases, say, foodgrains). That is just the kind of solidarity that it is so hard to even imagine at a global level. What sort of similar solidarity could possibly be envisaged between peasants in India and whoever consumes the exported basmati in metropoles abroad? Or take perhaps a more realistic example.

These commentaries I mentioned explain the solidarity between urban labourer and peasant as follows. Low procurement prices for foodgrains creates destitution among the peasantry and forces their migration to the cities, which then, in turn, creates hardship among labourers in the city due to the “reserve army” effect of that migration. So it is not just in the interests of the peasantry to demand higher prices but the labourer in the city to support this. And that was partly what was so encouraging about that rally. But now can you imagine anything like this solidarity emerging in the present frameworks of political culture between white workers in the cities in the U.S. bordering Mexico and the potentially displaced migrant from Mexico to these cities? Trump’s entire support base has emerged precisely because of such solidarity being out of the question.

So the only feasible solidarities among different sectors of working (and workless) people are really on or within the site of the nation. You can have flash events like Seattle a few years ago and a few other things like that; you can have the World Economic Forum annual meetings, but admirable though these things certainly are, they do not constitute sustained movements of the sort that puts any serious pressure on the light patchwork form of international governance that global finance allows. Real change will come through movements on national sites, and parliamentary political parties in specific nations will have to be alert to what these movements are demanding and formulate their electoral platforms in accord with the interests articulated in these movements. This last point is what Sanders and Corbyn understood in their intra-party parliamentary campaigns, and such success as they have had in enlivening their respective moribund Clintonite and Blairite parties has been due to precisely this alertness on their part. But in countries of the South, pretty much all the causes that surface in these movements (with very few exceptions) are eventually pursuable only within delinked political economies. To pursue them within a neoliberal framework of globalisation makes them hostage to the anxieties about capital flight. In Europe too, as the experience of Greece has shown, there is only heartache and frustration for the Left if it seeks to have it both ways.

We have explored a lot of different themes around populism, including the realistic ways to think about alternatives and solutions to globalisation. Can you say something by way of summary about your line of thinking and argument on the subject.

My dialectic has been something like this. I started out by saying that the fact that there are very different and even contradictory contents to populisms should not make us regard populism as a contentless phenomenon and look to trivial (contentless) features of it that are in common (such as the charisma of populist leaders), even if there were such trivial features in common (which I doubt there are; Corbyn is hardly charismatic). Rather, we should look for something substantial and non-trivial that is in common, and I proposed that we should look at the common causal conditions that give rise to populisms with different, even contradictory, contents and show why they do. I then focussed on the right-wing populisms in Britain and the U.S. (speaking occasionally as well to the left-wing populisms in both places of Corbyn and Sanders). And I tried to diagnose the twin causal conditions that prompted these populisms. In doing so, I stressed not merely globalisation, which is an obvious causal condition, but the role of liberalism and its responses to populism as forming an essential part of the causal explanation of these populisms. It would be important to extend this analysis to other places, including to India under Narendra Modi.

Let me just conclude by saying a very brief word to tie up all this lengthy analysis with the two initial questions I posed.

The first question was how has “populism”, which is defined by dictionaries as “the opposition to elites by ordinary people” (surely a good thing) become a pejorative term? The points I made around what I called the “failures of inference” were intended as an explanation of that.

But what of the other question, what is the difference between populism as a way of combating elites and democracy? After all, democracy is intended to give ordinary people a chance to counter elites through representative politics. That is to say, if democracy calibrates representation with numbers and if we assume—surely, a safe assumption—that ordinary people outnumber elites, then willy-nilly democracy is going to provide a political mechanism for opposing elites. But then what is the difference between these two ways of opposing the elites, and why is populism even necessary when you already have democracy?

Power of unelected officials

Well, obviously, the answer lies in the insufficiencies of formal representative democracy. There is a great deal of literature on these deficiencies in democratic polities, but one point that is immediately relevant to this second question is that, unlike (liberal) democracy, populism also seeks (not always with complete coherence, after all what I called a “failure of inference” is a symptom of incoherence) to oppose something that democracy, it seems, has been powerless to oppose: the power of un elected officials with specific economic interests to dominate the formation of policies. The general powerlessness of democracy to prevent this is present in the fact that this domination exists with the general acquiescence of the elected representatives.

What do you mean by “unelected officials with specific economic interests”?

Just take a look at the roll call of support for both the Remain campaign in Britain and for [Hillary] Clinton in the primaries against Sanders (as well as in the presidential elections against Trump). It ranged from the IMF [International Monetary Fund], Wall Street, the OECD [Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development] and [George] Soros, to the Governor of the Bank of England. This shows the extent to which what underlies the political class that surfaces in mainstream democratic politics is a parade of corporate and banking elites. And if that is the underlying power centre in actually existing liberal democracy, then populism is bound to differentiate itself from this political class by whatever means (often incoherent, often by turning alarmingly close to fascist ideologies) that are available for it in a very constricted political culture, the sources of whose constriction I tried to present.

So, just to be clear, I want to stress two things that distinguish populism from actually existing democracy as we know it. First, because such democracy is dominated by the liberal frameworks of thought I’ve been describing, populism is to be distinguished from democracy by the fact that it is opposing an entire consensual orthodox political class (the legislatures and executive branches of these democracies) which has acquiesced in actually existing democracies to the policy-shaping control exercised by unelected representatives of the corporate and banking elites. But, second, that opposition is only instinctive and inchoate; it is often confused, and often in thrall to leaders who merely mouth that opposition while working to make the class represented by these unelected officials even more entrenched in their control. Both these points are essential to the diagnostic condition of right-wing populisms that we witness today. Populism is distinct from democracy in opposing something that democracy (in its pervasively liberal form that is present in actually existing democracies) is powerless to oppose, but the opposition it provides is often and mostly under-theorised and instinctive and largely counterproductive.

Changing notions of class

You have distinguished between populism and democracy. What about the difference between populism and class politics?

You are right to raise that point too. Populism has emerged as a renewed phenomenon in our times not only because of the limitations of actually existing democracy but because in the past many years class politics has been superseded. Two factors lie behind this latter phenomenon. First, old notions of class have broken down (for the reasons we traversed when outlining the loss of bargaining power of labour), and second, all sorts of special interests making demands on the state have emerged as a result of other groups (not defined in class terms) gaining benefits from state policies. (In India, Mandal provides the most obvious example, but there are diverse other examples.) These two factors make it necessary to introduce a new category of populism to understand what often goes on in the politics of resistance. Thus, for example, Sanders was trying to bring together many different special interests; his was not just an older form of class politics, though of course he did mobilise people suffering from unemployment and wage stagnation, but he also mobilised youth with crippling education debts, the elderly population marginalised without proper health insurance, incarcerated black populations ignored by the first black President in U.S. history, etc.

So you are saying that populism defined as “opposition to elites” is a concept that gets its point and rationale when we make both these differentiations from other forms of opposition to the elites by ordinary people: conventional democratic politics and conventional class politics.

Just so.

Fascism’s family resemblance

You have said a lot about populism, would you like to say something about fascism since that is a word now widely in currency to describe the right-wing populisms?

No, I wouldn’t, really. I find that to do so is a thankless enterprise. It just gets one into pointless scholastic debates about whether the situation in India or Hungary today is exactly like it was in Europe (Germany and Italy) in the 1930s and 1940s. These quibbles are tiresome and are not well motivated, theoretically nor, indeed, politically.

I have some sympathy for seeing the matter in the following way. (I am just going to state it and then walk away because I don’t really see that it is fruitful to discuss it in detail. I have no major investment in seeing it this way, so I don’t particularly want to defend it. I just think it is one sensible way to see it.)

If you put aside mathematics and perhaps the neologisms that natural science sometimes coins in its strict taxonomies, there are no definitions of concepts and terms. Interesting concepts simply don’t have strict definitions. Only trivial concepts do. Recall that Socrates said at the end of his life that the only thing he had managed to define ever was the term that we translate in English as “mud”. (He defined it as a mixture of soil and water, in case you are interested.) So, when you have a term like fascism, which had emerged in a specific historical context with certain features and with a loaded doctrinal connotation, you obviously can’t give any strict analytic definition of it. You have to just see if there is enough reason to think that those historical features are being replicated so as to prompt its appropriate use again. But now, again obviously, “replicated” is too strong. So, we would have to require something weaker. Let’s say, “approximated”. (Incidentally, that is why Wittgenstein once said that concepts should be thought of not in terms of definitions but in terms of “family resemblances”.)

If you recall in a previous interview with you, I had said that that is the reason why I don’t think that “secularism”, which had its origins in a European historical context, really applied to anything happening in India until after Independence (it played no serious role for Gandhi nor even Nehru till then), and indeed it only became to be seriously relevant in India after the 1980s when the European context for it was being replicated or approximated in India. So, we have to ask the same about fascism when applying it to India today or to Hungary or….

If we are talking about India, you then have to decide. Does the following amount to an approximation of what was happening in Germany and Italy in that fascist period? a) The existence of a vitally influential paramilitary organisation like the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh] working behind and influencing the state. b) The entire talk of “purity” in the Brahmanism that underlies the Hindutva outlook, mimicking talk of racial purity. c) The invoking of both the state’s police and Home Ministry apparatus as well as the invoking of “the nation”, “the people” (volk), etc. to stifle individual dissent and to undermine the institutions that would protect dissent from the state bearing down on it. d) The appeal to a glorious past of the superiority of a people being debased by the namby-pamby secular accommodation of despised outsiders and enemies within the nation (Jews then, Muslims now). e) Above all, the dispersing of these attitudes into the mentalities of the people by propaganda and by the sanction that some of them begin to feel is given to them by the state for brazenly criminal acts of lynching and other forms of brutality against minorities and Dalits. f) The role of the ABVP [Akil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad], mimicking the Balillas in Italy, tormenting dissident students on campuses across the nation. And finally, of course, g) the fusion of state and corporations, to use [Benito] Mussolini’s term, as is emerging in Modi’s economic ideal for the nation.

Well, everybody should decide for themselves if a) to g) amounts to a family resemblance to Europe in the 1930s. What else is there to say? If someone decides “no, it does not”, all you can do is just quarrel about their judgement or perhaps their taste. But there is no knockdown argument on either side. That is why I am really quite happy not to talk of fascism and talk merely of a pathological authoritarianism. For that I think we do have something like a theoretical argument and not just an appeal to a family resemblance. Here is how I’ve consistently presented that argument. I’ll repeat it here.

The state in polities broadly described as liberal democracies with political economies broadly described as capitalist are sometimes characterised by a feature that [Antonio] Gramsci called hegemony. This is a technical term, not to be confused with the casual use of that term to connote “power and domination over another”. In Gramsci’s special sense, hegemony means that a class gets to be the ruling class by convincing all other classes that its interests are the interests of all other classes. It is because of this feature that such states (which represents such a class) can avoid being authoritarian. Authoritarian states need to be authoritarian precisely because there is no Gramscian hegemony. It would follow from this that if a state that does possess hegemony in this sense is authoritarian, there is something compulsive about its authoritarianism. Now, what is interesting is that the present government in India keeps boastfully proclaiming that it possesses hegemony in this sense, that it has all the classes convinced that its policies are to their benefit. If so, one can only conclude that its widely recorded authoritarianism, therefore, is pathological.

This doesn’t mention fascism; it only mentions a pathology (though you might observe that Nazism has been frequently described as a pathology). And, moreover, nothing I have said explains the pathology. The argument merely establishes that it is a pathology and leaves it unexplained. And I think on the Left, one finds that this is generally true of fascism too. You see fascism is particularly vexing to the Left because the Left can’t take it within its explanatory stride. In this it is unlike imperialism. I think it is very plausible to say that imperialism is built into the tendencies of capitalism, so we can explain it more easily within a framework we can construct for the analysis of capitalism. But I don’t believe we have anything like an explanation of fascism that subsumes it to the outcomes of the tendencies of capital. It is not that we cannot have any explanation of fascism; it is not a mysterium, it is not even sui generis, but unlike imperialism, fascism is prima facie mysterious because any explanation that Left theorists devise for it will have to look at factors that go beyond the tendencies of capitalism. Certainly, capitalism and the crises it generates are the prompting conditions for fascism (and other approximate pathologically authoritarian states), but they do not suffice to explain it.

The neoliberal version of capitalism

The Oxford University Dictionary chose post-truth as the word of the year in 2017. The word and the world outlook behind that word are similar to that of postmodernism. Are we really living in a postmodern and post-truth age? How do you engage with these philosophical views? Marxist scholars such as Frederic Jameson make a critique of postmodernism by saying it is the cultural logic of late capitalism. How do you define the current age?

I’m too much of a philosopher to think that an age should be seen as falling under any philosophical heading. Perhaps it should not get any heading, but certainly not a philosophical one. My view of my subject is that it should remain modest in its aspirations and see its intellectual goal as only serving other disciplines (history, intellectual history, politics, political economy, law, sociology, anthropology, also art, literature…) by uncovering their conceptual foundations and offering piecemeal conceptual and critical analyses of them, rather than trying to sum up a whole zeitgeist. Thus, it’s best to leave philosophy out when describing our age and stick to less grandiose descriptions of it. I would be more or less satisfied simply to think of it as the “age (or better, the period) of the neoliberal version of capitalism”. That is what is meant by “late” capitalism, I assume. And I doubt that this period has a cultural logic. I also doubt it has a cultural logic. It has a distinct logic, it has a distinct culture, but there is no easy way of yoking these together in terms that bring together vastly disparate concepts. Such logic as it has is primarily given in the economic structures of the neoliberal phase of capitalism (though that may be beginning to come unstuck as a result of the chronic crisis that is setting in).

Such culture as it derives from these structures should be described in terms that stick close to that material ground from which it derives. So it would be quite accurate to think of that culture as one of rampant commodification. Or it would be quite accurate to describe it as a culture of obsolescence. But to then add that these are of a piece with postmodernism is to move to a much greater distance away from the material ground of derivation, and when one does that, one better have a very detailed number of carefully argued analytical steps by which one justifies doing so.

I’m not sure that I’ve seen those steps carefully enough specified by any theorist, including Jameson, much as I find him interesting.

There are genuinely interesting things in Jameson, of course. Just to mention one, he writes insightfully of “depthlessness” as a feature of postmodernist philosophy, by which, if I recall, he is suggesting that in modernism what is on the surface is always probed deeper, uncovering underlying structures, while in postmodernism all is declared to be on the surface. In modernism, what is on the surface is illusory, so the aspiration is to plumb the depth to unearth the real, whereas in postmodernism, the very idea of depth is shown in principle to be illusory and the aspiration to seek it is a principled pretension with nothing to legitimate it philosophically. All of reality is on the surface.

Marx, Freud & Nietzsche

By these lights, Marx and [Sigmund] Freud are both modernists. Their hermeneutics of suspicion takes the form of saying that there is more than what meets the eye at the surface, more than ideology (Marx) and conscious behaviour (Freud) to be probed, uncovering structures of reality at a greater depth: economic structures, structures of the unconscious. Even someone like [Friedrich] Nietzsche, by these lights, I would say, counts as a modernist rather than a postmodernist, uncovering a will to power behind surface phenomena such as the avowed morals of conscience and humility in Christian doctrine. But in postmodernism, the hermeneutics of suspicion takes the form of there is less here than meets the eye, where deconstructive methods are intended to leave all on the surface, meaning or signification itself being deflected and deferred in the play of signs because signs lack the transparency to reach down to reference or signification. What I don’t find I am able to do (and I don’t really get any plausible instruction from Jameson on how to do it) is Jameson’s derivation of this postmodernist outlook from ideas of commodification or obsolescence that he rightly mentions as symptoms of late capitalism. I think at best there is an interesting analogy. Postmodernist philosophical outlooks and a pervasively commodified culture have this form of depthlessness, it is true, but I don’t see that a greater explanatory connection is made between the two by deriving both from the same source: late capitalist neoliberal economic structures. I am inclined therefore to restrict cultural descriptions of what actually derives from late capitalism only to commodification, obsolescence (where those descriptions of the culture sticks close to the economic phenomena) but not to postmodernism, which is at an extrapolated distance from the economic phenomena, a distance that is at best and at most bridged, as I said, by an analogy. Analogies are not explanations or derivations. I hope I am being clear.

What, then, about post-truth?

Yes, now in your question earlier, you suggested that talk of post-truth may be of a piece with theoretical positions characterised as postmodernism. I don’t think that can be quite right. I assume you say this because there is some sort of scepticism about the deployment of notions like “objective” truth in postmodernist philosophical positions, which are often taken to be unblushingly committed to a kind of “relativism” about truth. But that scepticism and that relativism is very different from the current phenomena that the term post-truth is intended to describe.

Before we get to post-truth, therefore, let me say something about relativism regarding truth, which is said to define a lot of postmodernism. I think there are different issues involved in relativism regarding scientific truth and relativism and nihilism regarding matters of truths in the domain of value and culture. Regarding the latter, there is actually an interesting and carefully constructible explanatory or derivational story to tell which relate themes of relativism about value and culture with the nature of capitalism and the intellectual history around the rise of capital. I do think that cultural relativism and relativism about values evolved out of an outlook that is closely tied to the rise of capitalism. And in telling this story, I don’t think we can make a clean break between modernism and postmodernism, as is sometimes suggested in Jameson. Modernism and its commitments are entirely continuous with and indeed I would say derivationally responsible for the relativism regarding values and culture that has come to be embraced by what we call postmodernism.

My own view is that it is the scientism that emerged in the modern period that is the underlying source of relativism in postmodern philosophical positions regarding value and culture. (By scientism, I mean a distorting sort of centrality that is given to science in the modern period.) As a result of this distorting centrality, the very idea of nature (the very idea of the world around us) began to be equated with what the natural sciences study. It is this scientism that declared that there is no more to nature, that there are no properties in nature other than what the natural sciences study. I believe this is a superstition of modernity. As a result of this superstition, nature got evacuated of all value properties since natural science does not study values. Values thus got relegated to our subjective mentality, our desires (later, via doctrines like utilitarianism, to our subjective utilities) and their more purely cultural constructions. This is the large ground for relativism about values.

Scientism & capital

What do you see as the connection between scientism and the rise of capital?

The rise of modern science in the Early Modern period in Europe was much more than the rise of newly formulated, highly explanatorily powerful, laws of nature (the most systematic presentation of which were, of course, to be found in [Isaac] Newton’s Principia). There emerged an outlook or ideology that, wholly and without remainder, equated the very concept of nature with what the natural sciences study. This equation was facilitated by very specific modern institutions, which grew around modern science and the further worldly alliances that these institutions around science forged. All this did not really happen until the second half of the 17th century, the Royal Society formed in 1660 in England being a major player in it initially. Though people like [Francis] Bacon, Galileo [Galilei] and [Rene] Descartes had all earlier converged on such an ideology, it didn’t have social effects till institutions around science developed to advance it in these alliances formed with both religious orthodoxy and with commercial interests. That did not happen until Newton’s heyday in England. The Royal Society, which consisted not just of scientists but mandarins in the surround of science, lined up with the Anglican Church (high rather than popular religion; popular religion in fact opposed this turn) and with commercial interests to promote this view of nature. What they were opposing was the idea that nature was sacralised, an idea everywhere present in popular religion. This idea alarmed these orthodoxies of the Royal Society and Anglicanism and early capitalist interests, which for sometime now were by brute force privatising the commons to turn agrarian living into what we would now call agribusiness. These orthodox alliances dismissed the sacralised view of nature as a dangerous “enthusiasm” that was partly responsible for the turmoil of the remarkable English revolutionary period of the pre-Restoration period. An early puritan radical leader such as [Gerrard] Winstanley, for instance (there were many others too), explicitly sought in popular religious views of a sacralised nature a great “levelling purpose”, to use his phrase: God’s presence in nature and matter made him available to the visionary temperaments of all those who inhabit His earth, not just to the university-trained divines possessed of learned scriptural knowledge and judgement. By contrast, for the Royal Society’s mandarins, nature was brute, material and inert (it was “stupid” to use Newton’s term in Opticks). For them, God must be given a place external to nature, a more purely providential status, a clockwinder responsible for setting an inert universe in motion from a position outside of nature and matter, not a divine source of inner dynamism responsible for motion from within (sacralised) matter and nature.

Now, since, in general, value was widely thought to have a divine source, the desacralisation of nature by these worldly alliances that relegated God to a cosmic exile had the effect of evacuating nature of value properties as well. The motivations for deliberately ensuring this were closely tied to the rise of the interests of capital. It mattered for commercial interests that there should be no obstacles to taking from nature. This was essential to the conceptual foundations of capitalism. Human beings had taken from nature for millennia, of course, but in all social worlds prior to the modern period, there were rituals to show attitudes of respect and restorative return to nature before cycles of planting and even hunting. It’s only in the last 300 years with the rise of capital that we have come to think that we might take from nature with impunity. The desacralisation of nature and its attendant evacuation of properties of value (what was I calling the total equation of nature with what the natural sciences study) was essential to the modern outlook that allowed for that.

But many argue that it is unscientific to say that nature contains properties that the natural sciences cannot study?

Yes, they do. But that is an elementary fallacy. In claiming that nature has value properties, I am not saying anything unscientific whatsoever. You can only say something unscientific if you contradict some proposition of some science. But no science contains the proposition: “Natural science has complete and exhaustive coverage of nature.” That is simply not a proposition of any science. Only philosophers and public intellectuals say such silly things, scientistic philosophers who insist that there can be no questions about nature that are not science’s questions. It is sheer superstition, a superstition of modernity to match any superstition of tradition. (If a scientist like [Richard] Dawkins says it too, it is not qua scientist that he says it. It is something that he says on his own time as a philosopher or public intellectual.)

You have been described as an atheist, and yet you would call this a superstition of modernity?

Right. There is no contradiction here. It is very simple to sort out the issues.

Speaking for myself, it is true that I cannot subscribe to the view that value properties have a sacred source. But it does not follow that value must be evacuated from the world (including nature) just because of its desacralisation. Desacralisation of the world and disenchantment of the world are two different things. The former does not entail the latter. To say that the world contains no divine properties is perfectly compatible with saying it contains value properties. Indeed, a great deal of the destruction of the environment would have had conceptual obstacles if one saw value properties as intrinsic to nature. A great deal of the culture of obsolescence and commodification would have had conceptual obstacles if we conceived of objects as having intrinsic value. The point, then, is this. To be opposed to science, i.e., to be unscientific, is to give unscientific answers to science’s questions. So, for instance, creationism does that. It gives an unscientific answer to a question in science about the origins of the universe. But to be opposed to scientism, which I am, is a quite different thing. It is not to be unscientific. It is rather to insist that not all questions, not even all questions about nature, are science’s questions. The question of value is not a scientific question, and since nature contains value properties as well as the properties that natural science studies, there are questions about nature that are not science’s questions.

Now, to get back to postmodernism and relativism; relativism about value and culture, at its deepest, was made possible by the evacuation of value from nature and from things and consequently making values have their entire source in our own mentality (our desires, our subjective utilities, our preferences, to use the contemporary social science term, our moral sentiments, to use Adam Smith’s term) and its cultural constructions. And the variability of these constructions coming from the cultural variability of the human desires and mentality from which they flow laid the philosophical foundations of relativism. That is the distant conceptual source of one kind of relativism (the relativism regarding value and culture) that are said to characterise the postmodern. And so, in my view, the modernist tendency to scientism is entirely complicit in the generation of the eventual postmodern forms of the relativisms regarding value, indeed nihilism about values, that are distinctive of our own time.

I have only told a story about the rise of relativism and nihilism regarding values that links it to the conceptual foundations of capital. The question of relativism about scientific truth is a different set of issues. The most powerful and interesting critiques of objectivist notions of truth have come from historians and philosophers of science, not philosophers like Nietzsche or [Jacques] Derrida. I would not call their critique postmodern. Thomas Kuhn, for instance, in his very influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions can hardly be seen as postmodernist, though I don’t doubt that someone willing to trample with great big boots on obvious distinctions will want to assimilate him to postmodernism.

Kuhn showed the extent to which something cognitive like scientific inquiry was nevertheless a practice. He showed how much it was affected by institutions, by funding, etc. He demonstrated how an ideal of scientific inquiry in which scientists just give up on theories that are presented with recalcitrant evidence and seek new hypotheses instead is simply not applicable to how scientists actually proceeded through the history of science. He showed how much scientists stick to their guns, make adjustments, add auxiliary hypotheses to their existing ones in order to retain their cherished hypotheses and save their theories from refutation. Pierre Duhem had already anticipated Kuhn in this, as had the philosopher [Willard Van Orman] Quine in much more abstract terms. But it was Kuhn who, looking at a long span of the history of science, took on the ideal of the objectivity of scientific inquirers very explicitly and argued that it just did not fit the practice of science.

Bruno Latour, some years after Kuhn, continued with this sociological critique of the objectivist ideal of scientific inquiry with far more flamboyant rhetoric and is sometimes described, perhaps correctly, as a postmodernist. But I would be surprised if he himself has not come to regret the effect that some of his polemics have had in discrediting science itself and helping to give rise to all sorts of lunatic denials of the conclusions about climate change by climate scientists. Latour, who has great concerns about the environment and has written interestingly on it, is, of course, strongly opposed to these climate change deniers.

There are many things on which I strongly disagree with Latour. His work describing Walter Lippmann as being a more perceptive thinker than [John] Dewey airs some of the most wrong-headed ideas of democracy and politics that I have read in a long time. But on issues of climate and nature, he is on the side of the angels and has a lot of interesting things to say.

But, I have been making a more underlying point, tracing the ideological attitudes about nature in the modern period to the conceptual foundations of capitalism. I really do think that sustained harms to the climate are endemic to capitalism and it all goes back to the history and the intellectual history of the Early Modern period that I just briefly outlined.

Are you a relativist about truth yourself, whether scientific truth or truths about values and culture?

No, I am not a relativist, but I don’t think it is an easy thing to argue against relativism, and I certainly don’t think you can argue against it by setting up some ulterior notion of truth and some misleadingly idealised notion of science, which has little relevance to how science is actually practised in its institutions and throughout its history. Kuhn definitively showed that.

I don’t think I have the time to set up the conceptual apparatus to convey why exactly I am not a relativist, but I can just say very briefly indeed what the very general direction of thinking is by which I reject relativism. You see, I don’t really think it even makes sense to say truth is relative to my perspective on the world (or relative to my culture or my theory). It doesn’t make sense because it presupposes that one can step entirely outside of one’s perspective (or culture or theory of the world) onto some Archimedean position and talk about one’s perspective as a whole from that position outside it. And claim that truth is relative to it. But there is no place we can stand outside one’s perspective or culture or theory of the world. There is no view from nowhere. And so truth is just truth simpliciter, not truth relative to this or that perspective or theory. Of course, I (each one of us) judge that this or that proposition is true and make truth claims by the best lights I have in my perspective, my theory of the world, my cultural standpoint.

What other lights do I have? But to say that does not mean that truth is relative to my lights, my perspective or theory or culture. I would have to step outside my perspective to say the latter thing, and it is that stepping outside that is impossible. It is a bit of nonsense to think that it is possible. It literally makes no sense to say that we can do that. So relativism about truth is not really even a meaningfully stateable doctrine.

To fully explain all that, I’d need a lot more conceptual apparatus, but that is a very crude and simple statement of the general drift or direction of why I think there is no relativism.

Incidentally, if you want to read more about the subject of relativism, especially about values and how they affect culture and politics, you may want to look at a long and detailed report that Prabhat Patnaik and I wrote for the International Panel on Social Progress, where in the theoretical part of the report some of these issues of relativism, reason, identity, etc., in social and political and cultural matters are addressed. (You can find it in Chapter 20 of the report. The chapter is on the topic of “Social Belonging”, and he and I were jointly the lead authors of the panel on that topic.)

WithHolding truth

So you are saying that post-truth issues are not really related to or continuous with issues about relativism regarding truth nor with postmodernist philosophy, generally.

That’s right. I think they are a quite different set of issues. For one thing post-truth is very specifically focussed on politics; it is most often used to describe certain elements that have entered very recently in the political arena, most ubiquitously in the U.S. but increasingly in other countries too. And for another (though not unrelatedly), it is used to describe certain alarming and cynical tendencies that have emerged in social media, as it is called, that affect politics, both electoral politics as well as the ethos of politics generally within which electoral politics operates.

To fully understand what is distinctive, if anything is distinctive, about such political phenomena, you have to record the continuities with the past as well. It is not entirely de novo, by any means.

On these questions about politics and post-truth, first of all, we should make a rudimentary distinction between withholding the truth and inventing the “truth”. These are different phenomena.

The first of these has been around for a very long time in the political arena. It is not in the interests of those in power to have information widely disseminated. Democracy—by which I mean substantial democracy, not just procedural or formal democracy—depends on information being widely available to the electorate (to ordinary people, away from the centres of power and privilege) so that they can exercise their vote in formal democracy from a position of cognitive strength. (By the way, this is precisely what Walter Lippmann did not want in politics. He was, in this sense, deeply undemocratic.) Elites, those in or close to power and privilege, for that reason don’t like democracy to get too substantial. That is why elites, whether political or academic, keep stressing “expertise” rather than “knowledge”. Knowledge is something that anybody in an electorate can, in principle, acquire and possess. Everyone has the cognitive capacity to do so. All that is needed is the time to acquire it and its accessibility (whether in the media or in the various levels of the education system). Expertise, by definition, is something that only a few possess. It would not be expertise if the mass of people possessed it.

One strategy, then, by which truth is withheld in the political arena is for those in power to present it as expertise, something that only the cognoscenti near power possess, unavailable to the public at large.

There are other less subtle ways of withholding truth, of course, censorship and self-censorship of those who write and broadcast in the media. In the U.S., even the so-called liberal media are notorious for withholding the truth about what the American government and its allies are doing all over the world. And, of course, there is never any fundamental critique of capitalism by this liberal media. In India too, the media are abjectly subservient in recent years to power and privilege. And a lot of people, [Noam] Chomsky and [Edward S.] Herman, most extensively, have demonstrated how much of this owes to the corporate stranglehold on the media in liberal democracies.

And, of course, a different kind of stranglehold (more directly by the state) exists in countries with other forms of government. All this is widely known and hardly bears repeating.

Inventing “truth” is not just keeping vital information (information that is necessary for the electorate to vote knowledgeably) out of the public sphere and thereby reducing the prospects of a substantial democracy. It is a more aggressive intervention, and it too has also been around for sometime, often called spin in previous times. (For an earlier example of it, just take a look at the excellent film Inside Job to see how much spin or invention of truth high-ranking economists from Harvard and my own university perpetrated in order to discourage the regulation needed to avoid the 2008 financial crash.) But it has become much more a topic of discussion in the present, especially in the U.S., partly due to the unprecedented high jinx of a careening President (someone like [Silvio] Berlusconi, a comparable earlier figure in some ways, is nothing like the scale of Trump in this regard) and partly due to the cynical use of social media to influence electoral politics and the ethos of politics. It is these more recent things that post-truth was specifically coined to describe. And to the extent that it has started occurring in other countries too, the term is getting wider application.

Trump & trUth-telling

Do you think someone like Trump completely disregards the truth in all the lies he is caught out in telling by people who check the facts against his statements?

That’s a good question, subtler than it might seem on the surface. You see, there is a big difference between someone who disregards truth and someone, like the liar, who disregards truth-telling, as the liar does. Someone who lies disregards truth-telling. But the liar holds truth in regard and that is why he wants to invent it. Someone who disregards truth is quite different from the liar: he usually doesn’t care whether something is true or not, and his goal, unlike the liar’s, is not deception. He just wants to speak for the sake of other goals: like showing off or making an impression, or, in Trump’s case, to score points against opponents and come out on top, show them who’s boss, as if it was all a game. But there is no regard for truth. Just a move in a game. The liar’s goal, by contrast, is deception. In order to deceive, he has to represent himself as believing what he says even though he doesn’t believe it.

When Trump speaks something that is manifestly false, it is not really even intended always to deceive, so it is not a lie. His constituency may very well know that he doesn’t really even believe what he is saying. So, unlike the liar, he does not even want to come off as believing what he is saying. Rather, he is basically getting something across to his constituency of white working[-class] people and some other anti-elitist groups, something like “See, I just scored, I just won this game, I just thumbed my nose at those coastal liberal elites yet again. They can’t really touch me with all their superior, smug put-downs.”

And a goal like that is quite different from the goal of the liar. (Of course, while there is all this trumped-up, pardon the crass pun, game playing and point scoring, he is behind the smokescreen of these antics, doing horrible things like cutting taxes on the rich, dismantling health care, undermining environmental regulations—all the things that the Republican Party’s orthodoxy applauds, even as they descry Trump’s bad-boy behaviour; after all he is carrying their agenda far further than they had, while pretending to his constituency that he is fighting the orthodoxy of his party and really doing good things for them, for the working people.)

I’m not suggesting that Trump never lies or deceives. Sometimes he does. But often it is not a lie, it is this other thing that disregards truth rather than truth-telling. In fact, if you ask me, I think the term post-truth should be used to describe a political ethos in which one is never really sure which one is being perpetrated: lies or this other thing. One is never really sure whether it is disregard of truth-telling or disregard of truth (which is a total lack of interest in either truth or falsity). I think post-truth is a good term to describe this ethos, this confusion in the political air where one can’t even tell which form of invention of truth is going on, the liar’s or this other sort of public verbal game-player’s. There, I’ve given you a characterisation of what post-truth as a term should be used to describe. And sad to say, politics in the U.S. is very much being played out in this ethos in the last few years.

The other location for the invention of truth phenomenon is found on the Internet and social media, the runaway spread of rumour, innuendo and often sheer abuse to contaminate the ethos of politics; interventions intended to generate ideological passions rather than investigative reporting, making things up to have quick political effect, and which takes fact-checkers a long time to then correct, often too late to pre-empt the bad effects. This has become a matter of great concern to everyone, and obviously since the technology is fairly new, this phenomenon is relatively unprecedented at least on the scale that we have been witnessing in recent years.

Role of the Internet

Would you say then that, all said and done, the Internet in general is a technology that on the whole has had bad effects on politics and culture?

Like any technology, it is certainly susceptible to terrible abuse. But it also has a good side, obviously. After all, all sorts of very honourable dissident reporting and opinion pieces that could never get into the mainstream media publications or broadcasts can be found on the Internet. You can get virtually nothing outside the liberal consensus on the mainstream media. Just like you can’t get it in almost any classroom or seminar room. Only searches on the Internet make them available. All this is well known and often said about the Internet, of course. So, I am just repeating things everybody knows.

But what is less often said is that most people, most working people with a long day job and often long commutes, don’t have any time to look up the remote sites on the Internet where the truths, often withheld in the mainstream press, are available. That is the real problem in all of modern society. For them, the Internet is mostly a resort of recreation from the chores of work and family duties day after day. Fatigued by these chores and duties, they turn to whatever little frivolity they can get as recreation on the Internet. It is widely reported by surveys that most working people go to the Internet to either shop, to read about sports, or to read about celebrities, or (in the case mostly of men) to view pornography. So, the good and valuable things that would make a difference to politics and democracy, sites of real information unavailable elsewhere, tend to be viewed much more by the privileged who have time on their hands.

And that brings us full circle back to the fundamental issues about capitalism we began with. You can’t just deal with these issues by complaining about Internet technology. None of this is going to be corrected or changed unless you change the much more background conditions in which working people are completely locked into this life of stagnation, poverty, drudgery, alienation. There simply is no getting away from those deeper and fundamental issues.

Cognitive generosity

So, you would not lay the blame on the technology itself?

That’s right. The technology is neutral, as all technology is. It can be a site of good and bad. There is no point constantly bemoaning the Internet and social media. And actually, while we are on the subject, I should mention one thing about the technology of the Internet that is not only good but something I find rather moving. I had not realised until this technology came to widespread use that human beings possessed a certain rather touching trait. It is only this technology that has released this trait in human beings. If it existed before (which it no doubt did since traits, in the strict sense, are a product of evolution), it took this new technology to trigger it and manifest it in human social behaviour. I don’t know how to describe this trait exactly. It is a form of generosity, but it is a cognitive generosity, not a material generosity. It is the generosity of wanting to share whatever little knowledge one might possess with others. I had no idea that we human beings had this trait.

It really is not to be confused with material generosity. Someone who has never given a penny to Oxfam, nevertheless often has what I am calling “cognitive” generosity. She wants to share whatever she knows with everyone by putting it on the Web. Any little thing. Someone has made a good biryani; he will put the recipe on the Web. Someone has found a way of getting ink stains off clothes; he will write it up and put it on the Web. Someone has heard some fine music; she will post it on the Web. This is quite remarkable. You can’t just say they do it for the limelight. They often do it anonymously. They just want to share what they know, however humble. I could not have guessed that we had this trait 30 years ago. Only this recent technology of the Internet has made it evident to me that we have it.