Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Sitting in a fascist prison cell in Italy, Antonio Gramsci wondered about a predicament that faced communists like himself. In The Communist Manifesto(1848), Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote, ‘workers have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win’. But these chains were not merely material bonds, the chains of deprivation that prevented those who owned no property apart from their own ability to work from being fully free. These chains crept into the mind, suffocating the ability of most human beings from having a clear understanding of our world. Suffocated, the workers (who were formerly adherents of socialist and communist movements) moved towards fascism. They came to the fascist parties not because of clarity, Gramsci wrote, but because of their contradictory consciousness.

On the one hand, people who spend most of their time working develop an understanding of the ‘practical transformation of the world’. This framework is implicit in the workers’ activity, since the worker—given the theft of their time—is often prevented from having a ‘clear theoretical consciousness of this practical activity’. On the other hand, the worker has ‘inherited from the past and uncritically absorbed’ a suite of ideas and practices that help to shape their approach to the world. These ideas and practices come from all kinds of institutions, such as from the State’s educational apparatus, from religious institutions, and from the cultural industries. Such inherited ideas do not clarify the practical experience of the workers, but they nonetheless help shape their worldview. It is this duality that Gramsci calls ‘contradictory consciousness’.

If you accept Gramsci’s assessment, then the struggle over consciousness—the ideological struggle—is a material necessity. For generations of workers, the trade union, the left political parties, and left cultural formations provided the ‘schools’ to elaborate and to connect the consciousness of the workers and provide a powerful understanding of the world, the clarity to see the chains that had to be broken. Over the course of the past forty years, for a variety of reasons that we catalogued in our first Working Document, trade union membership has declined as have left-wing political parties. The ‘schools’ of the workers are no longer available. Contradictory consciousness is harder to elaborate, which is why there has been a drift of workers into the grip of organisations of social hierarchy (that are founded on social divisions of religion, race, caste and other such manifestations).

We are in difficult times, with the scales of history favouring the far-right—including forces that have divided our societies along these social hierarchies, such as caste and race, nationality, and religion. Globalisation has fragmented social life and has created a precarious situation where people are no longer sure how to make a living and are no longer able to live enriched social lives. The terminal crisis for globalisation came with the general financial crisis of 2007-2008. The agent of globalisation—neo-liberalism—had taken over social democratic parties across the world and compromised them. The field now opened for an alternative to the camp of globalisation. For a series of historical reasons, the Left entered this phase deeply weakened after the global financial crisis. The far-right, on the other hand, had two advantages. First, it did not have to try and create its constituency. Its base has been delivered to it by the hierarchies and divisions of history. It merely utilised these divisions to its advantage, one of the lines of division being religious belonging. Second, the far-right did not need to address the actual problems of the time, such as structural unemployment and the climate catastrophe, but it could simply stigmatise the Other (migrants, religious minorities) as a way to consolidate its power.

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research held a two-day seminar in Tunis (Tunisia) on religion and politics to build an assessment of the role of religion in the growth of the far-right. During the first session, researchers from our teams in Delhi (Subin Dennis and Pindiga Ambedkar), Johannesburg (Nontobeko Hlela), and São Paulo (Marco Fernandes) offered their presentations on the role of religion in each of their social and political contexts. Both the teams from Brazil and India spoke about the crushing growth of plebeian conservatism through the rise of Hindutva (in India) and the rise of Pentecostalism (in Brazil). They argued, as the Marxist intellectual Aijaz Ahmad noted, that these right-wing forces were founded ‘on an uncannily Gramscian principle that enduring political power can arise only on the basis of a prior cultural transformation and consent, and this broad-based cultural consent to the extreme right’s doctrines can only be built through a long historical process, from the bottom up’. In South Africa, the enduring authority of the African National Congress, largely although not exclusively rooted in secular modes of politics, and the failures of churches to make a decisive entry into politics has allowed the country respite from these trends.

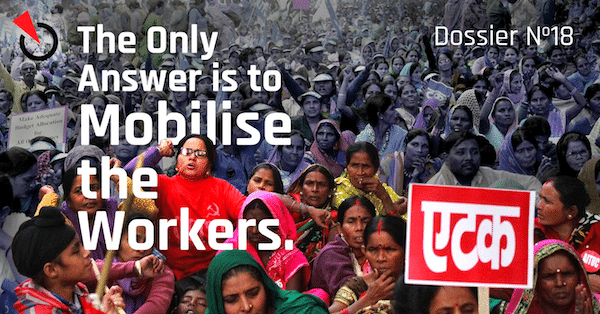

K Hemalata, President of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), addressing the March to Parliament by Child Care Workers organised by the All India Federation of Anganwadi Workers and Helpers (AIFAWH). New Delhi, February 2019.

During the other sessions, militant intellectuals and scholars from Turkey to Algeria, from Morocco to Sudan, presented their views on the role of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose politics are similar to those of the far-right RSS in India and the Pentecostal movement in Brazil. The presentations showed how the Muslim Brotherhood—as a mass movement—used its grip on education to shape the contradictory consciousness of the working class.

In the early writings of Karl Marx, there is a sense that religion is what the workers turn to as a way to gain some solace from the harshness of capitalism. As Marx wrote in 1844, ‘Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people’. This is a powerful statement, one that seeks to understand why it is that people turn to religion. Today, however, this is not adequate. More is needed. We need to understand how these organisations prey on the psycho-social problems that have escalated amongst the working-class. They provide services—however limited—to heal the great stresses of our time. Such a praxis of therapy draws in workers, eager for community and for the social welfare delivered through these organisations. We need a more robust assessment of the role of religion in our times, which is what our research hopes to produce.

What is the antidote to these ideologies and institutions of social hierarchy? To build institutions of the people—including trade unions and community organisations. But this is an enormous challenge in our times when socialist formations are atrophying at high rates. That is why our researchers in Delhi went to talk to K. Hemalata, the president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU). This interview forms our Dossier no. 18 for July, The Only Answer is to Mobilise the Workers. We strongly recommend that you read it, study it, and circulate it. Hemalata comes to her post at the union from her leadership of the All-India Federation of Anganwadi [Child-Care] Workers and Helpers. She ends the interview with the strong line that is its title—the only answer is to mobilise workers. This statement would warm the heart of Godavari Parulekar, the Indian communist leader who spent her life building the citadels of the working class in the factories and the fields.

The Only Answer is to Mobilise the Workers. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Dossier no. 18 (July 2019).

Over 90% of India’s workers are in the informal sector, most of them without any chance of unionisation. CITU has six million members, a considerable number but still not enough in a country with 1.3 billion people. Over the past decades, CITU has developed a series of strategies to organise informal workers, whether it be child-care workers or workers in small factories. Hemalata talks forcefully about the need for trade unions to take up issues of social hierarchy (patriarchy, caste, and fundamentalism) and to organise workers where they live, not just where they work. She talks about the need to organise not only the workers, but the communities in which they live. CITU’s ideological clarity and organisational suppleness have allowed it to build a strong federation, which has been in the lead in the massive general strikes that have convulsed Indian politics, with some with 200 million workers on strike.

Over 90% of India’s workers are in the informal sector, most of them without any chance of unionisation. CITU has six million members, a considerable number but still not enough in a country with 1.3 billion people. Over the past decades, CITU has developed a series of strategies to organise informal workers, whether it be child-care workers or workers in small factories. Hemalata talks forcefully about the need for trade unions to take up issues of social hierarchy (patriarchy, caste, and fundamentalism) and to organise workers where they live, not just where they work. She talks about the need to organise not only the workers, but the communities in which they live. CITU’s ideological clarity and organisational suppleness have allowed it to build a strong federation, which has been in the lead in the massive general strikes that have convulsed Indian politics, with some with 200 million workers on strike.

Matters remain grave. The rains have started in India. This has brought some respite from the catapulting heats waves that have claimed the lives of construction and agricultural workers. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has just released a report on the difficulties of working on a warming planet. But the ILO’s recommendations are weak: more mechanisation and more skills development. The real antidote in the long-term is for better policy to stem the climate catastrophe that addresses the root cause—a brutal economic system (capitalism) that seeks to reproduce capital at the expense of the planet and its inhabitants. In the short-term, the antidote is to prevent the brutalisation of workers by pushing for more trade unionism and other forms of working-class organisations. In Kerala (India), the Left Democratic Front government hastily banned work from 11am to 3pm in order to give workers respite from the heat (please see my report). More creative solutions and strategies are needed to confront a system that is at risk of destroying the planet and those who work and live on it.

Warmly, Vijay.

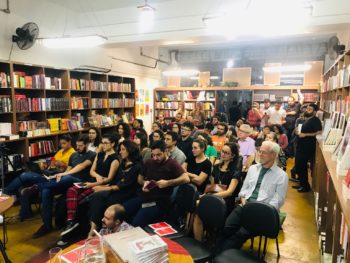

PS: this week, in São Paulo, our design team—Tings Chak and Ingrid Neves—did a presentation on art and revolutionary politics. They talked about Dossier no. 15 (April 2019)—The Art of the Revolution Will Be Internationalist. As part of their presentation, they displayed posters from the Organisation of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAAL) as well as posters by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. I wanted you to have a look at this wonderful display-