In Message to the Grassroots, a speech given in Detroit in late 1963, Malcom X famously observed that ‘Of all our studies, history is best qualified to reward our research.’ More recently, in The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia (2019), Benjamin Dangl examines the political work that has been undertaken in Bolivia to contest elite and colonial histories by recovering and affirming histories that take popular agency and struggle seriously. He argues that this work has offered ‘a bridge between generations, a way to share stories of oppression and resistance and, as a result, move people to take action’. This work requires actively researching, thinking, and writing against what the Haitian intellectual Michel-Rolph Trouillot called the ‘silencing’ of the radical histories of the oppressed by forms of colonial power—a ‘silencing’ that has been so effective that it has often made these histories ‘unthinkable’.

In post-apartheid South Africa, the rich histories of struggle against colonialism and apartheid came to be largely monopolised by the ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC). The story of the ANC was told in a way that foregrounded the role of the elite within the organisation. The new elite that formed around the ANC and the state mobilised claims about the past to legitimate its own authority, including its authority to suppress new forms of popular struggle. New struggles, including those with deep roots in the struggles of the past, were often ascribed to external conspiracies and criminality. As the ANC became more authoritarian during Jacob Zuma’s presidency (2009-2018), it presented the history of struggle in acutely masculinist terms, with the military actions foregrounded. This displaced the memory of popular struggles organised from workplaces and rural and urban communities, struggles in which women often played a central role.

Similar to the case of Bolivia, the best-organised of the new forms of popular struggle that have emerged after apartheid have explicitly affirmed the recovery of popular histories of struggle as important political work. These forms of struggle, which threaten to disturb the hegemony of the ruling class, have faced severe and often murderous forms of repression. In the land occupations organised by Abahlali baseMjondolo in Durban, for example, history is invariably given a central place in political education.

A century after its formation, the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) has largely been forgotten, but its history is extraordinary. The explosive growth of the ICU—which took the form of a trade union on the docks in Cape Town, a peasant movement in the rural Eastern Cape, and a squatters’ movement in Durban—in the 1920s was astonishing. The ICU wove Garveyism, syndicalism, and Communism into forms and histories of struggle with pre-colonial roots, expanded across Southern Africa without regard for national borders, and counted people from various African countries and the Caribbean in its leadership, as well as people who were Indian and mixed race. Today — in a time in which the history of struggle is relentlessly refracted through the prism of elitism, in which various forms of chauvinism are proliferating, and in which state-driven xenophobia is increasingly resulting in state and popular violence against migrants from elsewhere in Africa, and Asia — there is much to be learnt from the history of the ICU.

We Are Building Up a Union*

We are building up a union

With which we hope to save the land

I.C.U. are its initials

In its ranks we take our stand.We shall show by workmen’s council

How to banish sweated ills

How to raise the black man’s status

How to conquer strife that kills.Union means an all-in movement

None outside to scab upon us;

With folded arms we’ll stand like statues

Sing our song but make no rumpus.Forward then in one big union

All in which we’re organised

Solid phalanx undivided

No more shall we be despised.I.C.U. spells workers only,

I.C.U. – fraternity

I.C.U. means liberation;

I.C.U. – ‘Labour holds the key’

* This poem from the ICU is displayed at the Workers’ Library Museum in Newtown, Johannesburg. No attribution is given to an author.

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in the port city of Cape Town in 1919. It rapidly spread across the country and into the wider region, including the countries that are now Namibia, Lesotho, Zimbabwe, and Zambia.

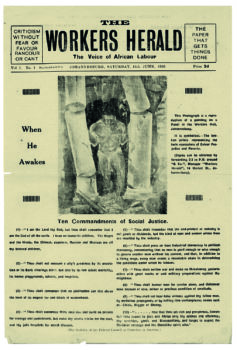

The Workers Herald (Official Organ of the I.C.U.). Wits University, Historical Papers Research Archive.

In his autobiography, Clements Kadalie—who became the first black national trade union leader in South Africa—recalls walking down Darling Street in Cape Town on a Saturday afternoon in 1918. Kadalie had arrived in Cape Town from Nyasaland (which is now Malawi). He was born and educated in a mission school and came to Cape Town from Rhodesia (which is now Zimbabwe), where he had worked as a mine clerk. He wrote that it was ‘the systemic torture of the African people in Southern Rhodesia that kindled the spirit of revolt in me’. That afternoon he was pushed off the pavement, and then assaulted, by a white police officer. A white passer-by, A.F. Batty, intervened. Batty had bee n a trade unionist in Britain and was a socialist. The two began working together politically and decided to try and start a trade union to represent black workers on the docks. They called a public meeting on Buitengracht Street on 17 January 1919. Here they formed the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (ICU) with 24 members. By December of that year, the ICU, working with an established syndicalist union, the Industrial Workers of Africa (IWA), was able to call a strike that shut down the docks for three weeks.

Radical Currents in Cape Town

As Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker show in The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (2000), revolutionary ideas often circulated through port cities during the colonial period. Cape Town is no exception. In 1808, people enslaved on farms outside of Cape Town rose in revolt. The slave revolt was led by a Mauritian slave tailor, Louis, and included people born in the Cape, as well as India, Ireland, and what is now Indonesia. The slave revolt was inspired by the Haitian revolution against slavery, which came to a victorious conclusion on New Year’s Day in 1804. News of the revolution in Haiti most likely reached enslaved people on farms outside of Cape Town via Caribbean sailors and dockworkers.

More than a century later, the ICU emerged out of the general black ferment—including riots, strikes, boycotts and anti-pass campaigns—that developed in most towns, and many rural areas in South Africa, after the First World War.

There had been considerable popular dissent in Cape Town for some years, both on the docks—the largest employer in the City—and in the shanty towns. The shanty towns surrounding the city date back to an outbreak of the bubonic plague in 1901 when Africans—stigmatised by colonial racism as being ‘unsanitary’—were blamed for the rapidly spreading illness and subjected to armed attacks that chased them from the city. The plague had in fact been brought to the city by rats in the hay bales that accompanied horses imported from Argentina for use in the Boer War.

Under the system of segregation, single African migrant workers were supposed to be confined to the Dock Native Location; African families were confined to the Ndabeni Township. The township, on the periphery of the city, had no streets or street lights, was adjacent to a sewage dump, and was surrounded by a patrolled barbed wire fence. It was a carceral space, a ghetto. Nonetheless, it soon become massively overcrowded, with the result that land was occupied and shack settlements were built across the city. As is common across space and time, shanty town militancy tended to peak when residents were threatened with evictions.

The Social Democratic Federation, formed in Cape Town on May Day in 1904, was an important precursor to the ICU. It mobilised for workers’ solidarity across race and ran soup kitchens, a book shop, a Socialist Hall with regular public events, and a printing press. It organised a union, strikes, and the direct appropriation of bread. It also organised trips to the beach, a choir, and even socialist christenings. Some of its more radical members called for armed direct action under a black flag aimed at seizing the land and factories and placing them under workers’ control.

The major upsurge in political militancy around the country at the end of the First World War in November 1918 was sparked by returning soldiers who were expecting a better deal, as well as by rampant inflation. The IWA, formed in Johannesburg in 1917 on the model of the Industrial Workers of the World, called its first mass meeting in Cape Town in 1919. Fred Cetiwe, one of its key figures, was from Qumbu in the rural eastern side of the Cape Province. After being fired from his job in Johannesburg for his leading role in the South African National Native Congress (SANNC) campaign against the pass laws, Cetiwe came to Cape Town and lived in Ndabeni, which was seething with political energy in the face of a threatened ‘slum clearance’. In 1920 the IWA would start working closely with the ICU. The SANNC, founded in 1912, would become the African National Congress (ANC) in 1923.

But syndicalism was not the only radical idea in the air on the docks in Cape Town. Marcus Garvey’s ideas also had considerable traction among dockworkers from the Caribbean. This was significant for the ICU from the outset as its initial constituency included dockworkers designated as ‘coloured’ by colonial authority, as well as African workers and workers from the Caribbean.

In 1920, the ICU would make its first breach across the borders of the colonial state when James La Guma, a Communist whose son Alex would go on to become a great Communist novelist, was sent to set up a branch in Lüderitz, in what was then South West Africa, and is now Namibia.

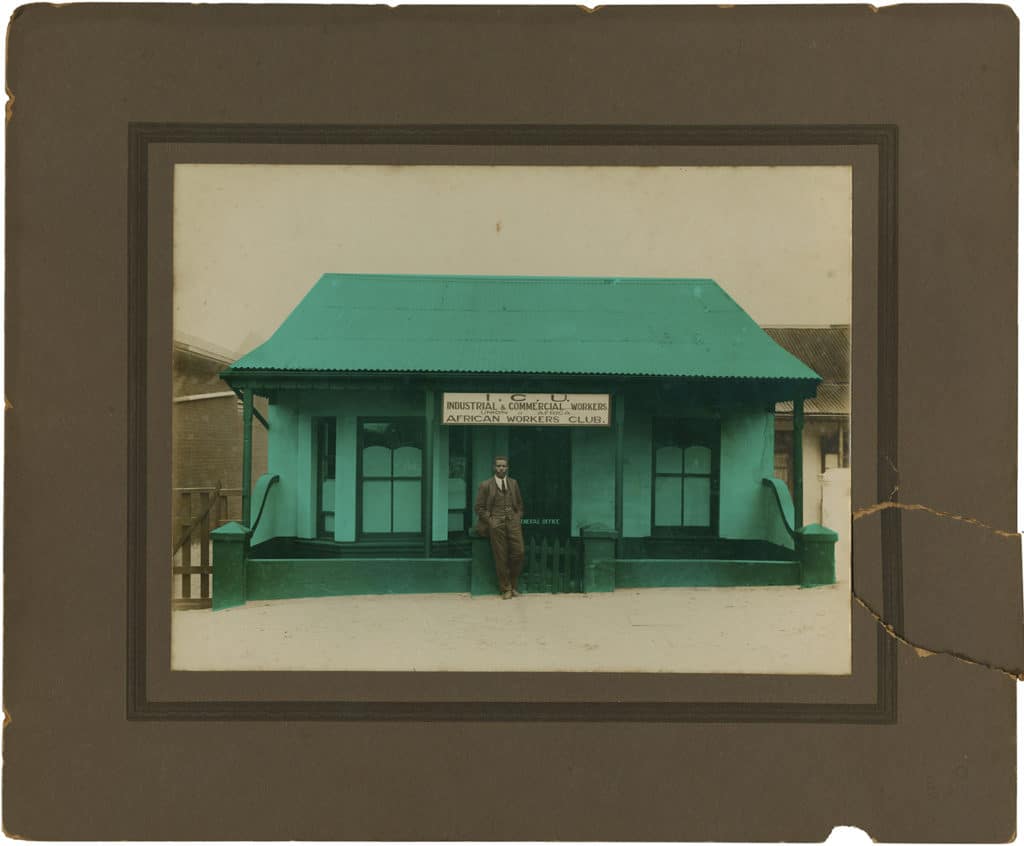

A.W.G. Champion standing at the entrance of the African Workers Club, 25 Leopold Street, Durban. UNISA Archives.

One Big Union

The dominant opinion in the SANNC opposed attempts to organise workers independently of the nationalist movement, which was firmly under the control of the aristocracy and the professional class. But in July 1920, H. Selby Msimang, a founding member of the SANNC and a newspaper editor who had become an effective labour organiser, called a conference of working-class leaders representing a number of unions in the inland city of Bloemfontein. The thirty or so delegates to the conference decided to create ‘one great union of skilled and unskilled workers of South Africa’. They resolved to unite under the banner of the ICU. When Msimang was elected as the President and Kadalie was unsuccessful in his bid to become the Secretary, the two had a falling out. But the ICU quickly developed into a mass movement with support from workers, peasants, squatters, and intellectuals across Southern Africa.

At a time when women could not join the SANNC as full members, it is striking that one of the central aims of the new organisation was to take a position for equal pay for men and women and to ‘see that all females in industries and domestic services are protected by the organisation, by encouraging them to enrol in all branches of the Union and to help them obtain a living wage’. However, this was not achieved. At the height of its popularity, women made up around 15% of the union’s members. Despite this, the ICU did enable the emergence of some powerful women leaders, and the organisation’s stated commitment to gender equity in this period is noteworthy.

Samuel Masabalala—a leader of the ICU—returned from the conference to Port Elizabeth, an industrialising port city in the Eastern part of the Cape Province, where he tried to organise a general strike. Soon after, he was arrested in October 1920 on trumped up charges. When a crowd of three thousand gathered to demand his release, twenty-four people were shot dead and many more wounded. After the massacre, shop workers in Port Elizabeth slipped pamphlets into boxes of goods moving out to the country and, within a month, farm workers in the Orange Free State (a province in the centre of the country) had heard of the riot and were threatening their bosses. As it became clear that unions were taking inspiration from the Russian Revolution, there was a growing white panic about the ‘Red Flag People’, as the ICU was known to whites, amidst calls to mobilise commandos.

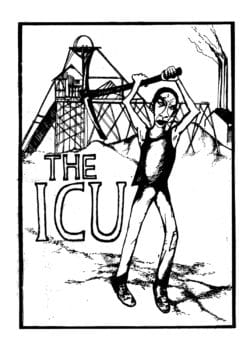

I.C.U. History Pamphlet Cover (published in 1983 by the Labour History Group). Wits University, Historical Papers Research Archive.

Msimang responded to the militancy that emerged in Port Elizabeth rather gingerly and in 1921 Kadalie assumed control of the union with the support of the Port Elizabeth branch. Caribbean leadership within the ICU—as well as the organisation’s close links to Garveyists in both the United States and Soviet Communism—drew the ICU to avidly follow anti-colonial movements elsewhere in Africa and in India. Cosmopolitan ideas from around the world were tied to grassroots forms of anti-colonialism that had roots in pre-colonial forms of popular politics. Helen Bradford argues that ‘from the conflict-ridden relationship between African nationalism and internationalism, there had emerged a seminal political perspective’.

To the growing horror of the white authority, the ICU dismissed the Congress—as SANCC, and later the ANC were known—as ‘good boys’ and the ‘old brigade’. At the same time, the ICU steadily expanded throughout South Africa. In April 1925, it played a significant role in a stay-away by 23,000 black residents in Bloemfontein that turned into a riot where police property was destroyed and men boldly marched through the city waving red flags. Five people were shot dead.

Explosive Growth

By 1925, more than 22,000 Africans were living—illegally and generally in shacks—in what were then peri-urban areas of the port city of Durban, in the province of Natal. Neighbourhoods like Mayville, Sydenham, Cato Manor, and Clairwood became the centre of a self-organised proletarian presence in the city. Housing conditions were far from ideal in what the mayor called the city’s ‘meanest quarters’. In these relatively autonomous and increasingly cosmopolitan neighbourhoods, popular culture was forged outside of direct white domination. People began to develop livelihoods outside of wage labour. The Natal branch of what was now termed the African National Congress (ANC) was largely absent from these spaces, focusing instead on the demands of a small mission-educated and propertied elite for incorporation into the colonial system. A key demand was for housing for ‘the better class’ of Africans.

In 1925, a branch of the ICU was opened in Durban. AWG Champion soon assumed control. Champion had been expelled from the Amanzimtoti Institute (later Adams College), a highly regarded mission school, for organising pupils in a militant protest against the school’s disciplinary regime. Like many of his contemporaries in the African middle class, he had a history of precarious work and had held eight badly paid jobs before becoming an organiser. Champion was a charismatic organiser and, within eighteen months of his arrival in Durban, the local ICU employed fifty-eight secretaries, clerks, and organisers.

Though the organisation was quite hierarchical and was largely run by cliques at the top level, branches often (although not always) had a much greater degree of popular control. Despite some instances of corruption and various internal fractures, the ICU expanded into rural areas at a rapid rate. In 1927, twenty-one village branches were opened in Natal in just three months. The union drew in around ten thousand pounds in Natal that year and the Durban branch claimed 27,000 paying members—an astonishing number given that the population of Africans in the city was estimated at between 35 and 40,000. The union claimed 50,000 members for the whole province.

The explosive growth of the ICU was not unique to Durban. Between 1927 and 1928, the movement spread across the country and branches were being formed in tiny villages with something of the velocity of Mao’s prairie fire. Rural Africans formed the bulk of the union’s estimated 150,000 to 250,000 members. Faced with strikes, refusals to work, cattle-maiming, and other more generalized forms of defiance, angry white farmers invoked state intervention on the grounds that this was not trade unionism but ‘general upheaval’.

In the Transvaal province, a conservative estimate put membership at 27,000 in 1927. Legal battles, which panicked white farmers, were key to the union’s ability to attract rapidly growing support, but they also exhausted the union’s funds and set up expectations that the union could not always meet.

Bradford writes that in Transkei—then a ‘reserve’, later a ‘homeland’, and now part of the Eastern Cape province—the ICU was ‘captured by its constituency’. Longstanding popular aspirations for land and autonomy fused with Garveyist ideas that were brought to the area by visiting speakers and the newspaper of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. A millenarian peasant movement cohered inspired by the hope that African-Americans were coming, with their own fleets and weapons, to free Africans. The slogan of the moment was amaMelika Ayeza! (The Americans are Coming!).

The union also spread through what were then Rhodesia, Basutholand, and South West Africa. Its discourse varied according to context and ranged from plans to buy land to encouraging people to take down fences and to plough where they liked.

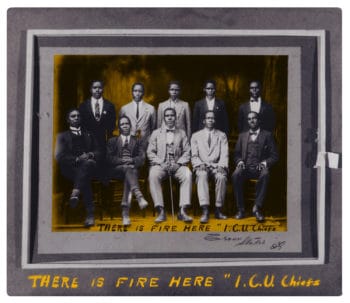

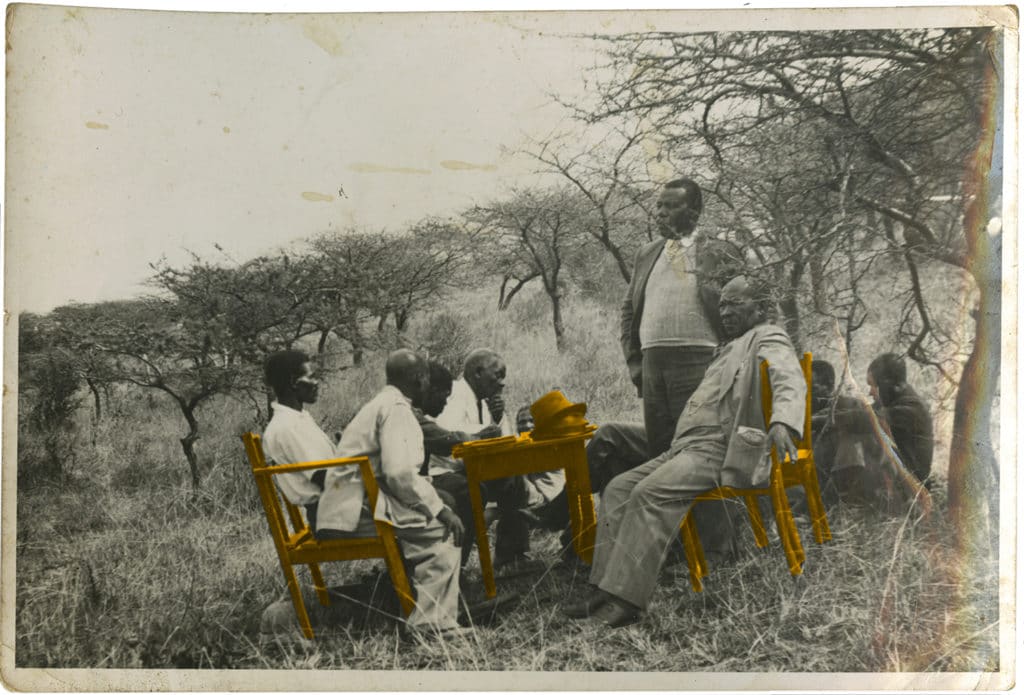

A.W.G. Champion )standing) and his best friend Mr. Tom Gwala (sitting), member of the I.C.U. UNISA Archives.

Rifts in the ICU

In Durban, the ICU mixed the syndicalism of the Industrial Workers of the World with Zulu nationalism, a broader African nationalism, and Garveyism. Paul la Hausse argues that ‘[t]hrough a sustained and generally successfully campaign of litigation aimed at a battery of repressive municipal by-laws, the ICU succeeded in capturing the imagination of Durban’s labouring poor’. The ICU quickly became adept at using the courts; their legal successes included lifting the curfew on African people, exempting African women from carrying night passes, ending the power of the police to make arbitrary arrests of African people, ending character references in passbooks, ending the prohibitions on Africans engaging in trade in the city and, most famously, ending the system by which African people were dipped, like cattle, in tanks of disinfectant on arrival in Durban. These legal victories won Champion huge popular support.

But, at the end of that year, Champion was suspended pending an investigation into claims of financial irregularities. In June of the following year, most of the Natal branches followed Champion as he left the national ICU to form the ICU yase Natal faction which developed what la Hausse called ‘a peculiarly local political culture’.

The ICU was not well received by the Zulu monarchy. In August 1927, King Solomon Zulu—speaking through a newspaper edited by John Dube, the founding president of the SANNC—ordered his amaKhosi (referred to as ‘chiefs’ by colonial authority) to ‘[k]ill this thing in all our tribes’. The sugar baron William Campbell gave active support to the King’s attempts to mobilise against the ICU. But not all of the amaKhosi accepted the King’s line. Those who supported the ICU were sacked by the colonial state.

The ICU explicitly opposed the elite politics of the ANC, whose members it derided as ‘amaRespectables’, and whose meetings it sometimes forcibly closed. After the ICU militia broke up a meeting organised by Dube for ‘respectable natives’ and amaKhosi to discuss ‘rotten social conditions’—caused not by the Municipality or colonialism but by ‘town natives’ who organised all night dances—Dube declared that:

Town Natives are out of control, and the criminal element is increasing … it is up to those in authority to break up these amalaita mobs [urban gangs]. The leaders of these gangs must be found out and dealt with. The heterogeneous mixture of detribalized natives in our large towns is a problem within a problem.

This discourse mirrors that of colonialism at every turn.

The ICU had its own hall at 117 Prince Edward Street in central Durban and ran night schools, staged music and dance performances, held large marches, made innovative use of the courts, and ran publications. Strikingly, the ICU members spoke in many churches, where it became what liberation theology would later call a prophetic voice, often leading to a profound re-orientation of their collective social vision. Bradford notes that there was significant ‘grass-roots support for the ICU’s court battles’ and concludes, quoting Friedrich Engels, that, ‘[s]imply in order to fight, achieving and defining specific legal rights is a key tactic whereby movements acquire “first a soil to stand on, air, light and space”. In Bradford’s estimation, ‘[t]he ICU was constituting itself as a rudimentary but nonetheless alternative power centre in wide-ranging spheres of social and state activities’. She adds that:

especially when infused with the creativity of members, even superficially moderate activities could point the way to the development of innovative, popular institutions. Fragmentary and partial though they were these attempts to broaden the conflict to various arenas of society were nonetheless significant. Thus, in addition to its meetings and office work, the ICU promoted alternative political and cultural practices to those through which whites shaped the ideas of blacks.

Much has been made of the lower-middle-class origins of most of the leadership, who were often people with some skills facing proletarianisation as a direct result of policies to give preference to white workers. But not all of its leaders shared these origins and nuanced studies show that, although leaders were frequently concerned with their own personal trajectories, the ordinary members of the ICU were often able to direct the leadership from below. Moreover, the African petit-bourgeoisie was being systemically pushed out of opportunities and forced to exist in a fundamentally precarious state—both economically and politically. Under these circumstances, a downward political identification was not uncommon.

However, that identification was not complete or uniform. Kadalie increasingly preferred to seek recognition from official forms of authority, to operate through officially sanctioned channels, and to step back from sometimes militant forms of direct action organised from below. This resulted in escalating tensions with the Communists in the movement, who supported direct action from below, and, at the meeting of the ICU National Council in December 1926, Kadalie, with the support of Champion, successfully argued for the expulsion of the Communists.

The following year, the union—which had a membership of a hundred thousand making it, up to that point, the largest trade union in African history—refused to support a series of strikes in Durban and Johannesburg. Instead of going to the striking workers, Kadalie declared that ‘strikes were wicked’ and sailed to Europe to mobilise international support. He was very well received and began, in a manner not entirely dissimilar to some forms of contemporary NGO politics, to see international pressure as a substitute for organisation.

But there were certainly still militant currents in the organisation, some of which looked to the developing anti-colonial movements around the world for inspiration, rather than looking to liberals or socialists in Europe. In May 1927, The Star reported that the Provincial Secretary of the Orange Free State, Keable ‘Mote, known as ‘the Lion of the North’, had told a village audience that ‘I am going to speak about the spirit of the age, which is that every nationality in the world is struggling for political freedom’.

The ICU constitution, adopted in December of that year, declared that:

As Karl Marx said, every economic question is, in the last analysis, a political question also, and we must recognise that in neglecting to concern ourselves with current politics, in leaving the political machines to the unchallenged control of our class enemies, we are rendering a disservice to those tens of thousands of our members who are groaning under oppressive laws and are looking to the ICU for a lead.

Christianity and Garveyism—both inflected with millenarian overtones—were also strong currents in the movement.

The Christian and Africanist inflections in the movement’s politics were encouraged by the fact that, as Paul Landau observes, ‘policemen had to monitor public assemblies to keep proper distinctions in place: meetings had to be religious, or cultural, or tribal, but never political, never concerned with changing people’s situations in this world’.

In 1928, the tremendous difficulties of sustaining a rapidly-growing mass movement led to serious fractures. As is so often the case, rivalries and tensions that had been manageable while the union was growing proved seriously problematic while the union was in decline. In Durban, the money for court battles against the municipality ran out and the union was reduced to petitioning. But there was still a general spirit of revolt in the air and Indian workers were able to successfully organise a number of unions.

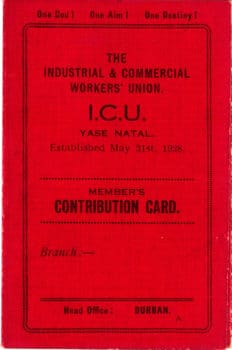

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union I.C.U. Yase Natal Member’s Contribution Card. Wits University, Historical Papers Research Archive.

In July of that year, William Ballinger was dispatched from Scotland to act as an advisor to the ICU. After being informed by Scotland Yard that Ballinger’s primary concern would be to oppose Communism among African workers, white liberals in South Africa were eager to pay his fare and his entry was granted by the State. Bradford, who notes that Ballinger’s ‘lack of experience in trade unionism was apparently outweighed by his anti-Communism’ observes that he was ‘the embodiment of liberal hopes’ for the ICU and cites the expression of the hope that Ballinger’s appointment as an advisor to the ICU would conclusively drive ‘a wedge between the native and the Moscow agitator’.

In 1929, the Communist Party of South Africa was established in Durban. Despite Champion’s suspicion of both the white leadership of the party and its position on property, some leading ICU yase Natal members joined the party. The rebellious spirit that had been in the air for some time began to take a millenarian form. In meetings, it was often declared that freedom was a few months off and, as Bradford explains, struggle took all kinds of forms ranging from ‘petitions, legal battles and passive resistance, through to work stoppages, land seizures and bloody warfare’. Pass officers—who were charged with enforcing segregationist laws that restricted the movement and rights of black South Africans—were attacked.

Confrontation in Durban

Opportunities for African women to find work in Durban were very limited. A 1930 survey showed that only 4% of African women had employment. Beer brewing became a key way for many women to earn a livelihood. The municipality’s attempts to prevent independent beer brewing, and to monopolise the sale of beer in order to fund the day-to-day oppression of Africans were deeply unpopular. The Sydenham shacklands were a hotbed of militancy and day labourers across the city provided a base of sustained opposition to the city’s beer policy.

In 1929, women began to organise against municipal canteens and for the right to brew beer in small towns across Natal. In November of that year the protests reached Durban. The protests were ascribed—as is more or less always the case in the colonial imagination—to a malevolent external agitator. Raids on domestic brewers had been relentless and destructive and often involved theft and harassment. In some parts of Durban, such as Sydenham where 10,000 Africans had settled, and where the state simply did not have the capacity to implement mass evictions, shack settlements had become spaces with a degree of autonomy from state control. But in May of that year, the local state signalled its intention to seize control of beer brewing and selling in Sydenham. The ICU quickly responded with two large marches from the ICU Hall in 117 Prince Edward Street to Sydenham—the first was headed by a brass band, a man in a kilt, and flag bearers carrying the Union Jack and a red flag with a hammer and sickle.

This movement of residents from what was then the urban periphery into the centre of the city, clad in red, created considerable white anxieties. One song, sung by marching domestic workers, expressed an unambiguous defiance:

Who has taken our country from us?

Who has taken it?

Come out! Let us fight!

The land was ours. Now it is taken.

In the middle of June, the dockworkers, who were housed together and well able to mobilise swiftly and effectively, declared a boycott of the beer halls. Champion was initially hostile to the idea but, in the end, had to lend his support. Once he was forced to abandon his first strategy—which was to use the language of Christian temperance to oppose the beer halls—the ICU was able to channel the ferment into a well-organised boycott.

During a meeting of 5,000 people at Cartwright’s Flats that was organised soon after a thousand picketers had clashed with police outside of a beer-hall, he declared that ‘from today the ICU is taking up the burden of the togt labourers [day labourers] and are in sympathy with them and are willing to die with them … We should get money in Durban and go and build homes outside … Down the [municipal] beer!’

ANC President J.T. Gumede also spoke at the meeting. In 1927, Gumede, James La Guma (a Communist from Cape Town and an early participant in the ICU), and Dan Colraine (a white Communist, had visited Communists in Brussels and Berlin), where they were warmly received by 10,000 people before making their way to Moscow as guests at the celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. At the personal invitation of Joseph Stalin, Gumede continued on to Georgia. He was very taken with the Soviet attempt to transcend ethnic nationalism and returned declaring, famously, that ‘I have been to the new Jerusalem. I have brought the key which would unlock the door to freedom’. At the meeting at Cartwright’s Flat’s Gumede declared that:

The ICU has taken the place of the Congress absolutely in Natal and that shows that the officers of the [Congress] were wrong to think that they could think for other people. … Now let us combine and take our freedom. … Today the Black man and the poor White man is oppressed … the money goes to the Capitalists … work together for the National Independence of this country.

The following year, Gumede was forced out of the Presidency of the ANC—largely due to his embrace of Soviet Communism—and replaced with Pixley ka Seme, a mission-educated man with degrees from Columbia and Oxford University who had married into the Zulu royal family.

On 17 June 1929, all five of the Durban beer halls were picketed by dockworkers and a white motorist was killed. Champion was taken to the agitated crowd by the police, where—according to both his own account and that of the police—he tried to calm the crowd and they dispersed after some time. But a white mob rushed to the ICU Hall to exact vengeance. La Hausse gives a concise account of the events:

White ‘vigilantes’ laid siege to the ICU Hall, and by evening close on two thousand white civilians, from ‘every class’, and three hundred and fifty policemen faced six thousand stick-wielding African workers. These Africans had poured from every quarter of town to relieve the beleaguered men, women and children in the hall and in the ensuing clashes one hundred and twenty people were injured and eight mortally wounded.

In the end, the ‘vigilantes’ destroyed the ICU Hall along with the instruments of its famous brass band. Protest spread to nearby Pinetown and the small towns of the interior. Although the Durban riots were soon crushed by the police, the municipal beer monopoly never regained its full authority. Resistance was soon taken up by the dock workers who, with the support of the Communists, organised against passes the following year at the cost of some lives.

In September 1930, Champion was banished from Natal for three years not—as Shula Marks shows—as a result of the beer hall riots but, rather, because he had met with the Zulu King, Solomon, in the aftermath of the riots. She argues that ‘it was through the Zulu royal family that the state hoped to ‘refurbish traditionalism’ and to strengthen its hold over the chiefs and its rural network of control. … The thought that Champion might himself use the same network and perhaps radicalize it was clearly disconcerting’. She also quotes G.N. Heaton Nicholls, president of the sugar cane planters’ association and an arch segregationist, who argued in a letter to the national government that ‘I think it is pitiable that instead of strengthening the aristocratic and conservative elements amongst the natives, we are driving them into the arms of native revolutionaries’.

The boycott of the beer halls continued for some time after the attack on the ICU hall. A massive and highly militarised early morning raid on the dock workers’ barracks in November, conducted amidst escalating white paranoia about a worker-led uprising, did not break the boycott, nor did a call for its end by the ANC. As late as 1936, sales at the municipal beer halls were still less than half of what they had been before the boycott.

By 1930, the political initiative in the city had shifted in favour of the Communist Party of South Africa—ironically in part due to the banishment of Champion. Amidst opposition from the ICU leadership, the Communist Party—led by dock worker leader Johannes Nkosi—organised day labourers to burn the passes that they were forced to carry, and that restricted their movement and subjected them to government control. On 16 December, more than 2,000 passes were handed in to be burnt before the police attacked the gathering, subjecting Nkosi to a serious assault that took his life on 19 December. Three others were also killed.

Dube refused to condemn the police and blamed the violence on ‘these new people who have left home to come and work here’. The presentation of political dissent as being consequent to people being out of place, and illegitimately in the city, was not a uniquely white phenomenon. It is a trope that is still invoked by leading ANC politicians in Durban today. The crushing of the pass burning protest marked the end of the first major sequence of popular protest in Durban.

The Communist Party went underground and more than two hundred of its most active members were deported. By 1931 the ICU was a spent force in South Africa, although various offshoots continued for the next thirty years, and it continued to flourish in Rhodesia until the 1950s.

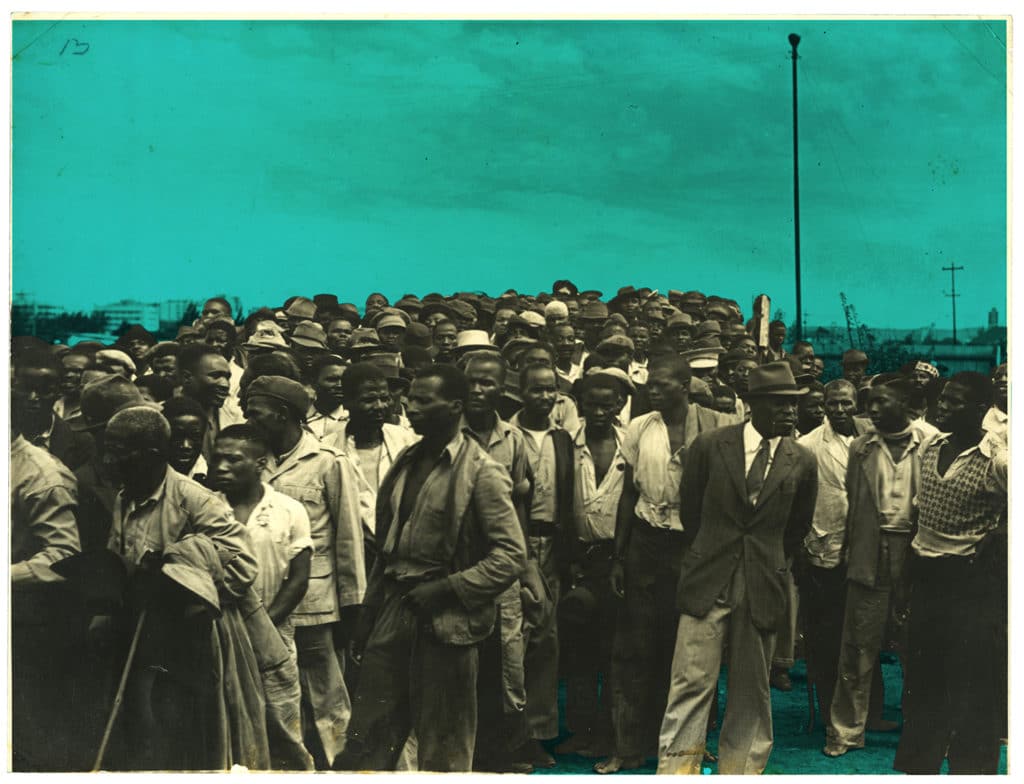

ICU meeting with police in attendance (William Ballinger ICU Adviser is also in attendance). UNISA Archives.

The Mental Sediment

We could say, with Rosa Luxemburg, that ‘[t]he most precious, because lasting, thing in the rapid ebb and flow of the wave is its mental sediment: the intellectual, cultural growth of the proletariat, which proceeds by fits and starts’.

ICU leader Jason Jingoes captured the essence of that sediment in an interview in The Herald in March 1927:

Although its initials stood for a fancy title, to us Bantu it meant basically: when you ill-treat the African people, I See You; if you kick them off the pavements and say they must go together with the cars and the ox-carts, I See You; I See You when you do not protect the Bantu; when an African woman with her child on her back is knocked down by the cars in the street, I See You; I see You when you kick my brother, I See You.

The ‘mental sediment’ left by the rise and fall of the ICU was global. In 1938 CLR James, the great Caribbean intellectual, wrote that:

It will be difficult to overestimate what Kadalie and his partner, Allison Champion, achieved between 1919 and 1926… The real parallel to this movement is the mass uprising in San Domingo. There is the same instinctive capacity for organisation, the same throwing-up of gifted leaders from among the masses.

Further Reading

- Bonner, Phil. ‘The Decline and Fall of the ICU: A Case of Self-Destruction? Essays in South African Labour History. (Ed). Eddie Webster. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1978.

- Bradford, Helen. A Taste of Freedom: The ICU in Rural South Africa, 1924—1930. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1987.

- Bradford, Helen. ‘Class Contradictions and Class Alliances: The social nature of the ICU leadership, 1924—1929’ in Resistance and Ideology in Settler Societies, (Ed.) Tom Lodge, Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1986

- Champion, A. W. G. The Views of Mahlathi: Writings of A.W.G. Champion, a Black South African, edited by M.W. Swanson and translated by A.T. Cope and E.R. Dahle. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press and Killie Campbell Africana Library, 1982.

- C.L.R. James. A History of Pan-African Revolt. Washington: Drum and Spear Press, 1969 (originally published in 1938).

- Collis, Victoria. Anxious Records: Race, Imperial Belonging, and the Black Literary Imagination, 1900—1946, PhD Thesis, Columbia University, 2013

- Cooper, Frederick (ed.), Struggle for the City: Migrant Labor, Capital, and the State in Urban Africa, Beverly Hills/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications, 1983.

- Cope, Nicholas. To Bind the Nation: Solomon ka Dinuzulu and Zulu Nationalism 1913–1933. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1993.

- Cope, Nicholas. ‘The Zulu Petit Bourgeoisie and Zulu Nationalism in the 1920s: Origins of Inkatha’ in Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3, 1990.

- Couzens, Tim. The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of H.I.E. Dhlomo. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985.

- Dangl, Benjamin. The Five Hundred Year Rebellion: Indigenous Movements and the Decolonization of History in Bolivia. Oakland: AK Press, 2019

- Jingoes, Jason. A Chief is a Chief by the People: The Autobiography of Stimela Jason Jingoes, recorded and compiled by John and Cassandra Perry London: Oxford University Press, 1975

- Johnson, David. ‘Clements Kadalie, the ICU, and the Language of Freedom’, in English in Africa, Vol. 42, No. 3, 2015

- Hemson, David. ‘Class Consciousness and Migrant Workers: Dock Workers of Durban’. PhD Thesis. University of Warwick. 1979

- Kadalie, Clement. My Life and the ICU. New York: The Humanities Press: 1979

- Landau, Paul. Popular Politics in the History of South Africa, 1400-1948. New York: Cambridge University Press: 2010

- La Hausse, Paul. Brewers, Beerhalls and Boycotts: A History of Liquor in South Africa. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1988.

- La Hausse, Paul. Restless Identities: Signatures of Nationalism, Zulu Ethnicity and History in the Lives of Petros Lamula (c.1881-1948) and Lymon Maling (1889 C.1936). Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2000.

- La Hausse, Paul. ‘Drinking in a Cage: The Durban System and the 1929 Beer Hall Riots’, in Africa Perspective, No.20, 1982

- La Hausse, Paul. ‘The Dispersal of the Regiments: African Popular Protest in Durban, 1930’ in Journal of Natal and Zulu History, Vol. 10, 1987.

- La Hausse, Paul. ‘The Cows of Nongoloza’ Youth, Crime and Amalaita Gangs in Durban, 1900–1936’ in Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1, 1990.

- La Hausse, Paul. ‘Beer, Social Control and Segregation’. Honours Thesis. University

- of Natal. 1980.

- La Hausse, Paul. ‘The Struggle for the City: Alcohol, the Ematsheni and Popular Culture in Durban, 1902—1936’. M.A. Thesis. University of Cape Town. 1984.

- Linebaugh, Peter & Rediker, Marcus. The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston. Beacon Press. 200.

- Marks, Shula and Richard, Rathbone (ed.), Industrial and Social Change in South Africa: African class formation, culture and consciousness 1870—1930. New York: Longman, 1982.

- Marks, Shula. The Ambiguities of Dependence in South Africa: Class, Nationalism, and the State in Twentieth—Century Natal. Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1986.

- Marks, Shula. ‘Natal, the Zulu Royal Family and the Ideology of Segregation’ in Journal of Southern African Studies, Vol. 4, 1977—78.

- Masilela, Ntongela. The Cultural Modernity of H.I.E. Dhlomo. Trenton: Africa World Press, 2007.

- Maylam, Paul, and Edwards, Iain (eds.), The People’s City: African Life in Twentieth Century Durban. Durban: University of Natal, 1996.

- Maylam, Paul. ‘“The Black Belt”: African Squatters in Durban, 1935-1950’ in Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol. 17, No. 3, 1983.

- Maylam, Paul. ‘The Rise and Decline of Urban Apartheid in South Africa’ in African Affairs, Vol. 80, No. 354, 1989

- Meli, Francis. A History of the ANC: South Africa Belongs to us. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1988.

- Mkhize, David. Ngavele Ngasho. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter and Shooter, 1965.

- Peterson, Bhekizizwe. Monarchs, Missionaries & African Intellectuals: African Theatre and the Unmaking of Colonial Marginality. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2000.

- Roux, Edward. Time Longer Than Rope: A History of the Black Man’s Struggle for Freedom in South Africa. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1948.

- Skota T.D. Mweli (ed.), The African Yearly Register: Being an Illustrated National Biographical (Who’s Who) of Black Folks in Africa. Johannesburg: The Orange Press, 1932.

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.

- Swanson, Maynard. W. ‘The City in history: the rise of multiracial Durban’ in John Bird Historical Society Proceedings, Vol. 1, No. 5, 1961.

- van der Walt, Lucien. ‘The First Globalisation and Transnational Labour Activism in Southern Africa: White Labourism, the IWW, and the ICU, 1904–1934’ in African Studies, Vol. 66, 2007.

- van der Walt, Lucien. ‘Anarchism and Syndicalism in an African Port City: The Revolutionary Traditions of Cape Town’s Multiracial Working Class, 1900–31. Labor History, Vol. 52, No, 2, 2011.

- Vinson, Robert Trent. The Americans Are Coming! Dreams of African AmericanLiberation in Segregationist South Africa. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2012.

- Wickins, Peter. ‘The One Big Union Movement Among Workers in South Africa’ in The International Journal of African Studies, Vol. 3, No. 3, 1975.