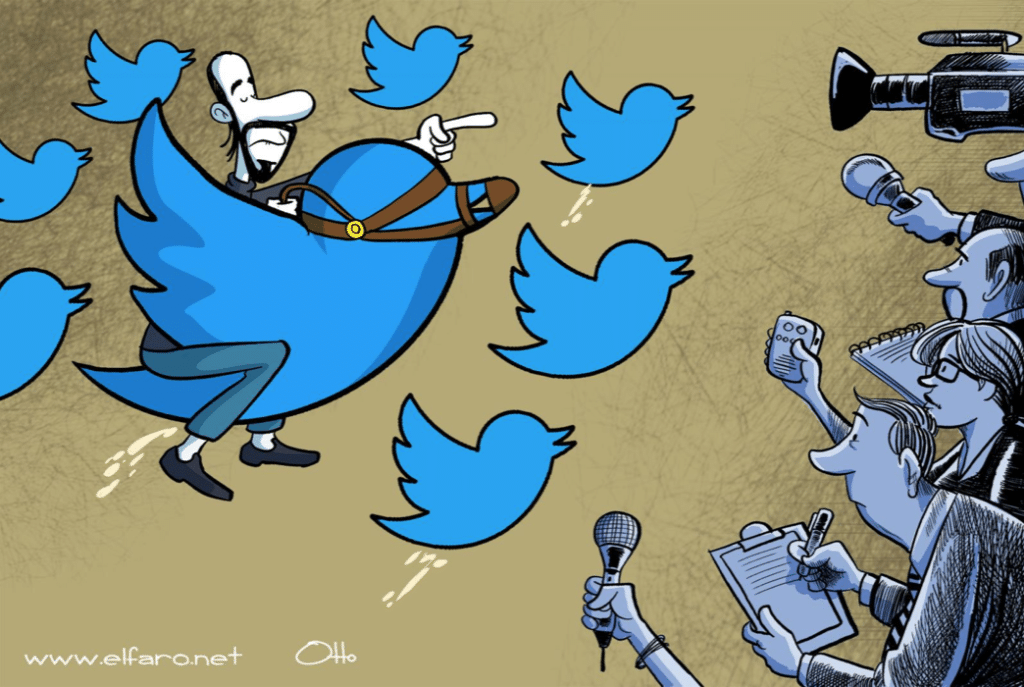

In a cartoon recently published on the Salvadoran news website El Faro, the country’s president, Nayib Bukele, is shown leading an army of blue birds—one of which he has harnessed and rides—toward a group of microphone- and camera-bearing reporters. Should there be any doubt on the part of the reader regarding the cartoon’s message, the title, “Attack the Messenger,” brings the point into sharper focus. The 38-year-old Bukele has frequently taken to Twitter to address criticism from the press, sometimes in a manner seen as unbecoming of a politician. “Attack the Messenger” reflects the uneasiness Bukele’s behavior has stirred among Salvadoran journalists, while also hinting at a more general anxiety about where the young president, who took office on June 1, will take the country.

Otto Meza, “Ataquen al mensajero” (“Attack the Messenger”), El Faro, May 3, 2019.

“Attack the Messenger” was drawn by Salvadoran political cartoonist Otto Meza, a calm, bespectacled 46-year-old, and appeared in El Farolero, Meza’s more-or-less weekly column in El Faro. Bukele has been a regular target of Meza’s pen in recent months, but El Farolero goes far beyond the nascent presidency in its coverage and deals with a whole spectrum of domestic issues. Indeed, many of the themes Meza uses to label his cartoons provide a stark overview of the issues facing contemporary El Salvador: “Migration,” “Inequality,” “Corruption,” “Transparency,” “Impunity,” “Historical Memory.”

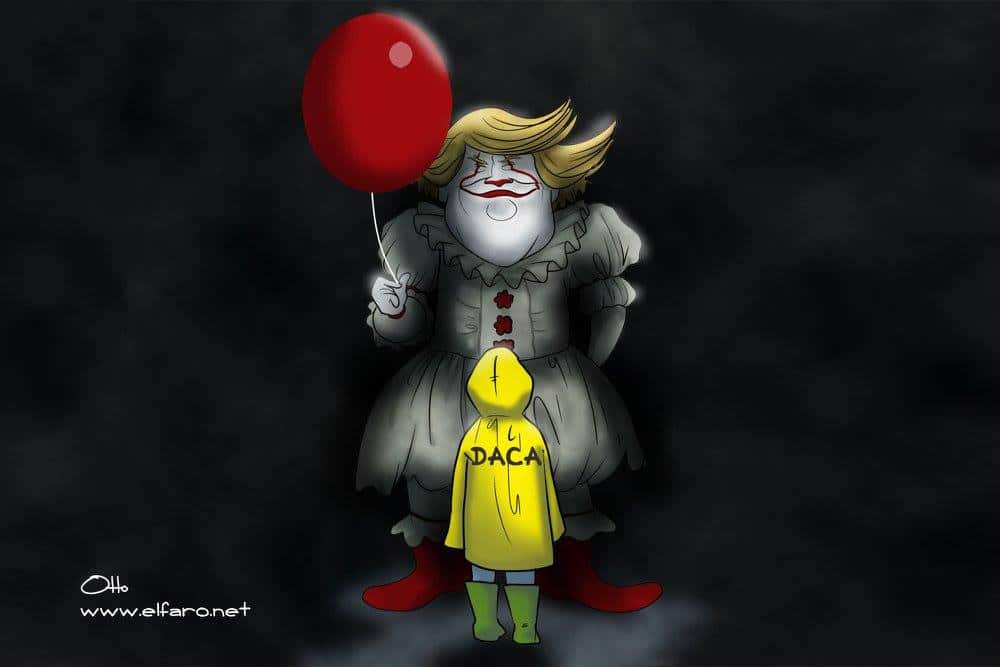

On top of El Salvador’s endemic problems, over the past several years the country has also become a favorite target of Donald Trump, another politician who makes frequent appearances in El Farolero and whom Meza describes alternatively as “a buffoon,” “a child throwing a tantrum,” and “someone truly dangerous.”

In “It. By Donald Trump,” Meza dresses the U.S. president up as the eponymous clown from the Stephen King novel and puts him face to face with a young child in a yellow rain jacket that reads “DACA” on its back.

Otto Meza, “It. By Donald Trump,” El Faro, September 5, 2017.

Born in 1972, Meza came of age during El Salvador’s twelve-year civil war, which began in 1980 when left-wing guerillas rose up against the government. In San Salvador, the country’s capital and Meza’s hometown, blackouts occurred commonly throughout the conflict. During evenings, Meza, having developed an interest in drawing thanks to an artistically inclined uncle and an early childhood exposure to Peanuts, began to “express how I felt through drawing.”

Meza also felt politically awakened during the war, although it might be more accurate to describe it as an awakening to the absurdities of politics. In his mid-teens, Meza’s friends began being forcibly recruited by both guerillas and the government and, as more and more of them began to die, Meza found himself developing a strong distrust of ideology and politics, because, “at a young age, I saw mothers cry for sons who died on the right and sons who died on the left.”

Vestiges of this attitude can be found in Meza’s cartoons, where politicians are invariably depicted in a negative light—though there are gradations to the harshness. Appearing in a jester’s hat could almost be considered a compliment coming from Meza, while those who have truly attracted his ire can expect something more along the lines of a Nazi armband.

In conversation, Meza is more sanguine about politicians. He admits that “there have been very good politicians in [his] country,” but explains that they do not appear in his cartoons because he believes that “politics and politicians don’t exist to be applauded, but rather to be scrutinized through the exercise of journalism.”

A chance wartime encounter with eminent Salvadoran cartoonist Carlos Ruiz Moisa—better known as Ruz—led to Meza’s first lessons in political cartooning. He was taught how to highlight a person’s features and advised that “to make a cartoon on a subject, you need to read a lot.”

Meza says that in El Salvador “there is an enormous tradition of cartoonists” that stems from the fact that “we’re very often telling jokes” and “cartoons are a good place to laugh at ‘untouchable’ [politicians].”

After high school, Meza spent five years in medical school before dropping out and pursuing a career in graphic design. He was hired as an illustrator in 2003 for a children’s magazine put out by La Prensa Gráfica, an establishment Salvadoran newspaper, and published occasional cartoons in the paper until he was made its editorial cartoonist in 2007 and given the opportunity to publish cartoons regularly.

But it was not until 2009, the year he became a contributor to El Faro, that he was allowed the editorial leeway necessary to give full voice to his political outlook. Whereas his previous workplace considered certain subjects too inflammatory for the Salvadoran public—for example, Meza says that he knew he “couldn’t touch themes related to the rights of the LGBT community, from any angle”—at El Faro he has “the freedom to choose [his] topics and approach the cartoon.”

Things have certainly changed. LGBT-related cartoons are a mainstay of El Farolero and, thanks to the topic’s universal relevance, have been some of Meza’s most popular work internationally. Meza remembers his surprise when, in a single day, he saw reproductions of his cartoon “#AgainstHomophobia” at pride marches in El Salvador and Spain. The cartoon shows an individual nailed to a crucifix with a drooping head, the face cut off by the bottom edge of the panel. Nailed to the crucifix above the head is a pride flag, beside which appear the words: “And more than 2000 years later, intolerance keeps making mistakes.”

Otto Meza, “#ContraLaHomofobia” (“#AgainstHomophobia”), El Faro, May 18, 2016.

Migration is another topic with international reverberations often addressed by Meza. While all Central American countries deal with the issue to one degree or another, El Salvador is disproportionately affected. El Salvador’s population is just 6.2 million, but it is estimated that some 1.2 million Salvadorans citizens live in the United States.

While Meza says that immigration is “complicated,” he is skeptical of Bukele’s use in a recent Washington Post op-ed of the word “lose” when referring to Salvadoran migrants in the United States. “I don’t know if the term is a political slogan or something with real meaning,” he says, mentioning that he does not consider an acquaintance who migrated to the United States to work as a doctor as “lost.”

One recent cartoon of note is “American Nightmare,” a take on the photo that circulated in June of drowned Salvadorans Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his 23-month-old daughter Angie. In a vein similar to Michael de Adder—the Canadian cartoonist who was fired for his own depiction of the photo—Meza ties the drowned migrants directly to Trump: their bodies are situated at the bottom of the panel while, in the upper half over a dark blue background, are the words “America First.”

Otto Meza, “Pesadilla americana” (“American Nightmare”), El Faro, June 25, 2019. The image pays homage to drowned Salvadorans Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his 23-month-old daughter, Angie.

On the more strictly domestic front, the looming issue now facing El Salvador is the Bukele presidency. For thirty years, two political parties dominated Salvadoran politics: the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance, both of which came to prominence during the civil war. Bukele, though a member of the FMLN during his time as mayor of San Salvador, ran for president with the center-right Grand Alliance for National Unity.

His defeat of the established parties in the elections this past February was a landmark for El Salvador, but Meza is wary of exaggerating the importance of the two-party system in Bukele’s victory. “Lots of people say that Bukele came to break the two-party system. I wouldn’t say it was the two-party system. There were two currents of thinking, the extreme right and the supposedly radical left. But both currents had one thing in common—both were corrupt.”

Based on Meza’s cartoons, you would think he has nothing but contempt for the new president. Bukele is depicted as vain and Twitter-obsessed, an opportunist without substantive political beliefs. When speaking about him, however, Meza adds some nuance to the opinions expressed in his cartoons. “He has some reforms for the education system that seem interesting,” Meza says, not without a hint of enthusiasm in his voice.

But Meza is quick to emphasize that Bukele’s Twitter attacks on the media and the resultant Twitter mobs are not to be taken lightly. Meza has himself been a target of these Bukele-supporting mobs—comprised “generally of anonymous accounts” and whose attacks he describes as “very visceral”—with the harassment becoming so intense in recent weeks that he had to temporarily shut down his Twitter account.

Given its superficial similarities to Mexico, a country notoriously dangerous for members of the press, it might be surprising to hear that, as Meza sees it, a Twitter mob is the worst response most Salvadoran journalists can expect to their work. And while there have been sporadic cases of murdered journalists—the most recent example Meza can recall is from the late 2000s—Meza is emphatic that he has never truly feared for his life.

Regarding the impact of political cartooning, Meza is modest but also hopeful he can have a positive influence on Salvadoran society. “I don’t think it’s useful for changing opinions. Instead, I think it’s useful for promoting tolerance.” He adds that he is also happy if he manages, “to irritate some [political] dinosaurs.”

Neither sentiment will surprise a regular reader of El Farolero.