The second month of the intifada is over, and the ruling class has not been able to stop what is occurring in Lebanon. This does not mean that it will not be able to do so in the future. But our steadfastness throughout this period in face of one of the most powerful manifestations of the capitalist system is in and of itself an achievement in the history of the region.

I say “our steadfastness.” By that word, I mean the steadfastness of groups that have never come together around a single issue: the working class, the middle class, the organized left, the liberals, the nationalists, members of political parties and independent individuals, as well as individuals forming the social bases of parties of the present political authority, collectivities which were never before consolidated by one party or one union or even several unions. I say “the strongest manifestation of the capitalist system” to indicate the sectarian form that has divided the population of Lebanon into sects, each entrenched and hardened in the face of one another. Mahdi Amel, the Lebanese Marxist thinker, says that the sect is a political structure, one which the capitalist system wishes to make into a social structure. This truth is what most are discovering in this uprising.

Between those who mock the revolution as a dance festival in the streets,1 and those who are paranoid about a joint local-foreign plot against the resistance movement in the region2 (probably due to their ignorance of the people’s position vis-a-vis US policies3 in this region), it is natural that the uprising in Lebanon would be rocked by destabilizing sentiments. Still, what is certain is that the vast majority in this intifada stem from the hungry and the sick: those unable to pay for hospital care, those hailing from families unable to repay bank loans, and from amongst those young women and men who are unable to find work and are pushed to commit suicide day after day.4

Let us go back to the beginning. Poverty in all its forms is what led the people to take to the streets. We do not know the unemployment rate with precision, but two years ago it was said to be approximately 27 percent, with one-third of the population living in poverty in 2018.5 But what we know with certainty is that I and most whom I know have been without work for many years, making a living from unstable and intermittent work. Social pressure in Lebanon prompts people to conceal their poverty or their state of economic crisis, because “poverty is shameful,” and because flaunting appearances and wealth is a virtue.

The societal norms created and entrenched by the leaders of the sects—which is to say, the ruling bourgeoisie cloaked by the sect—has long ago taught the working class that it is shameful to take to the street and to demonstrate and to demand their rights. But yet it is necessary for individuals and communities alike to be followers of the sect’s leader and humiliate themselves at his door, begging for crumbs. The current form of the state in Lebanon is restricted to tax collection for the ruling class and engaging in violence against “petty criminals.” Meanwhile, the state disclaims all other duties, allowing right-wing sectarian parties to distribute services to their followers according to their fealty, while plundering the lion’s share of the country’s wealth.

Oppression springing from years of silence has finally led people to talk about poverty today.6 Concealing poverty is not merely a question of concealing lack of social privilege. Concealment itself, in turn, naturally leads to a discourse which casts blame on the poor themselves: that they are poor because they are not seriously looking for work, or they do not work more than two jobs, or they do not accept to work under degrading conditions, or in particular, they do not offer obedience to the leader and beg for a job. Hiding poverty is also part-and-parcel of celebrating the existing system—capitalism and its neoliberal policies, which were implemented despite repeated warnings by left parties since the early 1990s, and by subordination to the sect and its leadership, socially, politically, and indeed systemically—a fact which we celebrate in this country; a fact which they wish us to think is unchangeable.

The result of breaking the fear of physical and social confrontation was that more than two and a half million residents of Lebanon—Lebanese women and men, refugees from Palestine, Syria, and elsewhere—stood against hunger and poverty and the state’s complete inability to carry out its duties.

Furthermore, what made us call what is happening an “intifada” and not “ordinary demonstrations or protests,” is that people began to step out beyond the parameters set by the regime—bright lines which mark the sect’s authority, beyond which lies a different authority: that of the state. In this way, people have broken with the chains of fear which tied their necks to the leader’s beacon, and told her the only exit from the crisis is to follow his leadership.

Many participants in the demonstrations talk about sectarianism instead of class struggle as they make the facile suggestion that “people’s refusal of sectarianism” is the needed solution.7 Yet they provide no evidence to support the idea that a causal relationship between sectarianism and poverty exists. This is a discourse which is supported by liberals in complete congruence with the dominant rhetoric, continuously fed by the mainstream right-wing media in Lebanon and which underscores that the crisis extends to the entire Lebanese system of government and the actual structure of the capitalist system.

The rekindling of class conceptions

There are several reasons for the severe disconnect between mainstream discourse and realities on the ground, but dominance of the neoliberal ideas of business tycoon and former prime minister, Rafic Al Hariri, is of particular importance. So-called political Hariri-ism—an approach that enforced neoliberal policies on the Lebanese state and worked on eliminating any space to talk about Marxist concepts, or to put forward the concept of class struggle—has dominated the entire post-civil war period. Alongside political Hariri-ism was a system of suppression focusing on silencing intellectuals, artists, and ordinary people who attempted to utilize class concepts. As a result, a Marxist mode of analysis was purged from everyday analyses and theories. The dominant discourse focused on the idea that the system is sectarian, and it fixed in people’s minds that the problem and solution were there as well.

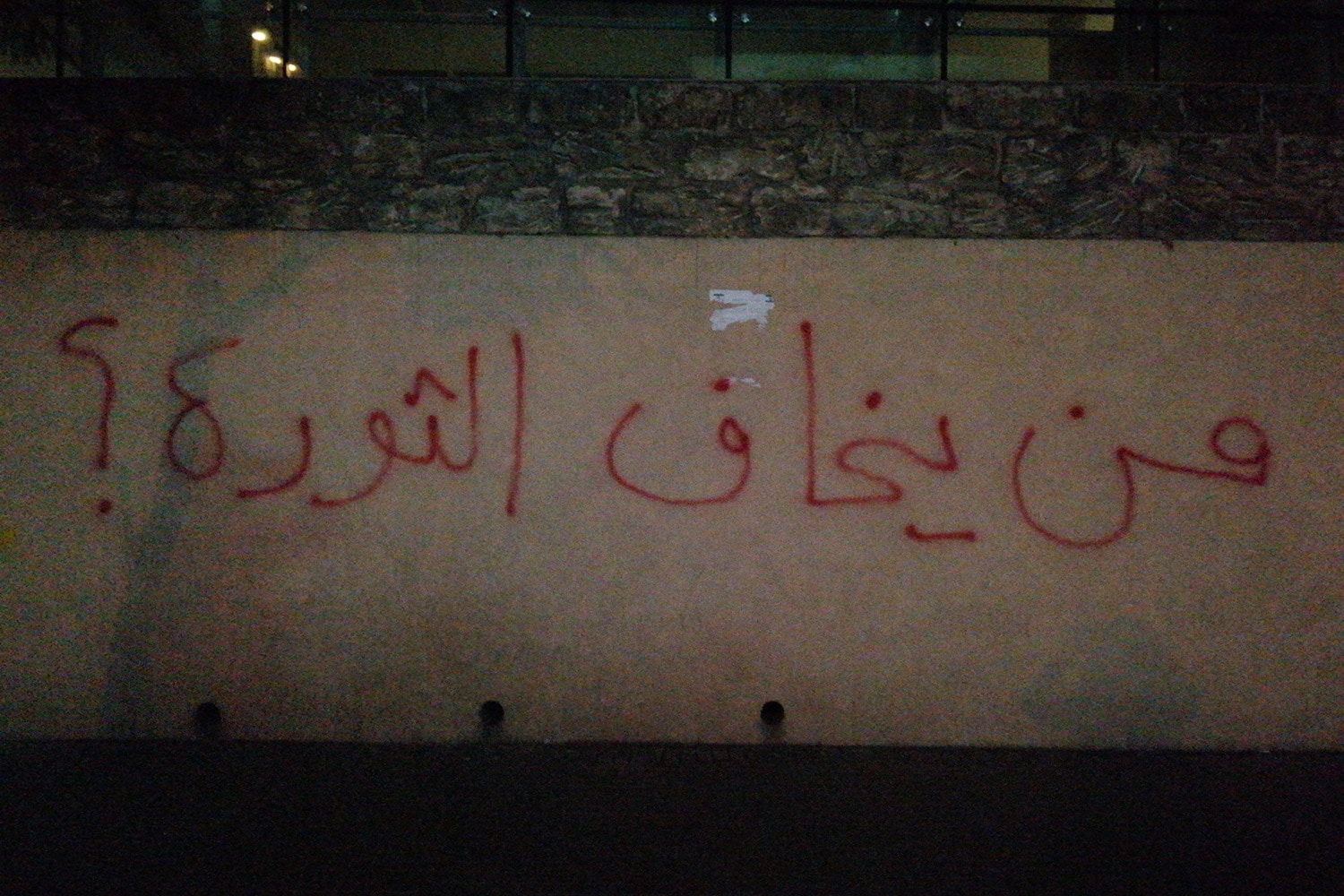

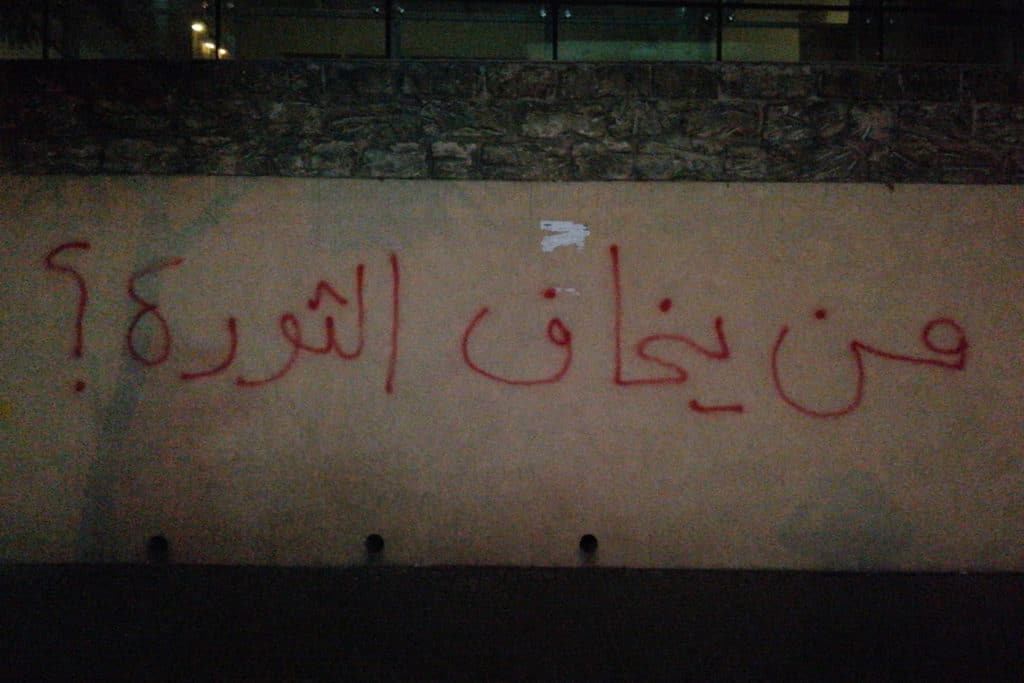

The uprising has removed any doubt about the viability of this tactic. Banning Marxist ideas from mainstream discourse and everyday discussions could not remove the reality of class, nor the fact that the struggle is manifestly a class struggle par excellance. As the slogans of the protestors makes clear—“us and them,” “the poor and the rich,” “stealing people’s wealth,” “looting,” “nationalizing banks,”… etc.—Marxian class theory is reasserting itself. Contrary to the narrative put forward by the media, there are—from the standpoint of the demonstrators—two classes: exploiter and exploited .8

What is happening today amidst the complete madness of the parties which control the ruling political authorities, and their desperate attempts to control or eliminate the uprising, is the revelation of their true fear: losing their grip over the streets of their corresponding sectarian communities and, in particular, an attack on the separation between the different communities of the working class which they have worked so hard to create. While the uprising demands a change in the social, economic, and political, these parties see this alternative as the inevitable end of their authority. On the other hand, the economic crisis and the collapse we are waiting for, if it reaches the level of more closed institutions and more employees losing their jobs, or the depreciation of the Lebanese pound, will reduce the possibility of these parties “reassuring” their bases, and restoring the bond of dependency to the leader.

Ruling class fear and retaliation

Therefore, the governing parties, after deploying violence in the form of the state security forces, resorted to three tactics that damaged the relationship of the intifada with specific groups, especially members of the Shiite community, or what has been called the separation of the Shiite working class (which was the first to rise up)—the sector of society supporting the so-called “Axis of Resistance,” from the intifada. These include threatening and inciting against the members of the Shia sect participating in the intifada, placing them under social pressure, stoking sectarianism between the intifada and members of the Shiite working class, and giving the green light as well as ordering armed men from Amal movement and Hezbollah to violently attack the uprisings in areas under the control of the Shia political couple;9 as well as the use of tools such as fake voice recordings and videos, social media sites and popular individuals (and influencers) to sow distrust about the uprising, casting it as the work of traitors, demonizing them through McCarthyite tactics. (The writer of this text has been called everything from a normalizer with the zionists, to liberal, to U.S. agent, simply because she organizes and writes against the rule of capitalist sectarian political parties.)

Walid Jumblatt’s Druze Socialist Party also used these tactics,10 but the Shiite parties’ use of them was far more impactful in terms of emptying the streets of individuals belonging to the Shiite community, due to the large numerical difference in the size of the two sects.

This hostile position of the two Shiite parties towards the uprising allowed the complete demonization of it by individuals under their banner, sometimes reaching the point of madness by blaming the uprising for the torrential rains that flooded the streets in early December, accusing the uprising of a conspiracy against the people by planning to cancel the construction of dams (Bisri Dam as an example) as part of the implementation of a plan to further destroy the already destroyed economy.

These methods have succeeded in cleaving the Shiite working class in particular from the intifada, to a greater or lesser extent. But they have also opened the door to wide-ranging discussions within the Shiite community, including those committed to following the fatwas of Hezbollah and who have believed its rhetoric about the feasibility and fairness of this system.

New stage of the intifada

As of early December, we believe that the intifada entered a new stage, as it developed in terms of its framework and composition since day one. This is a natural, logical, and healthy phenomenon. The tools of the intifada too, must be transformed and must evolve. To answer our favorite question, what is to be done? we start by looking at what the regime has destroyed, from coopting trade unions, to women’s/feminist groups and leftist parties, to forbidding the Communist Party—for many years and in many different ways—from organizing. Therefore, organization itself is the main tool of the current stage of the struggle, starting with discussions launched by legal groups, the Lebanese Communist Party, feminist groups, progressive and leftist individuals in all regions, until the establishment of organizational committees (nodes which could eventually become communes) that coordinate between each other and organize in their regions, and in that way the foundation of the revolution starts to take shape.

For, today the cow is dry. Businessmen stepped on her neck for years, extracting the last drop of milk. There is nothing left for them to fight for, except for the hopes of using us to beg either from the U.S., the E.U. or the Gulf States.

What the people say today to a stuttering, equivocating political elites—which one day rejects the existence of the crisis, another day tries to circumvent the intifada, and a third day casts it as the work of traitors—is: “your time is over.” The political elites claims their hands are tied by the nature of the system. But this is a system whose history and rules were written from day one by these same individuals. The people, in turn, say that the political elites created the crisis, and the time has come to put forth an alternative. The alternative must tend to the full range of issues—in politics, economics, society, religion, culture, agriculture, artistic creation, the environment, and education—throwing in the sea of Beirut and Tripoli, Abda, Saida, and Tyre, the leftovers of the hegemonic system.

We may be romantic in imagining that the street today creates a consciousness that our generation has never seen before in Lebanon. And perhaps it is the euphoria of this experience of trying to build an alternative. But it is also simply because we have no other option.

Notes

- ↩ Khalaf, Kamal. “Demonstrations of Lebanon.” Raialyoum, October 22, 2019.

- ↩ Khalek, Rania. “Technocracy now: The US is working to turn Lebanon’s anti-corruption protests against Hezbollah.” The Grayzone, December 1, 2019.

- ↩ “Death to America“, “we don‘t want colonization“, and “Beirut is free” were some of the slogans heard during the intifada’s demonstration in front of the U.S. embassy. This was one of several demonstrations organized in the last few years, in response to the U.S. interfering with the internal affairs of the country, as well as in support of the Palestinian cause. Dakishley, Samer. “Demonstrations in front of the American Embassy in Lebanon.” Midline News, November, 2019.

- ↩ Mohamad Zbib, as well as Drs. George Korm, Kamal Hamdan, Ghassan Diba, Charbel Nahhas, and Sami Atallah, were amongst the major economists in the past years to publish and conduct discussions around the economic situation, and to warn about te upcoming catastrophe. Al-Akhbar Newspaper’s Zbib created the “capital” appendix, which can be called one of the major sites offering information and analysis which incited the intifada. The capital appendix. Al-Attar,Sahar.“Charbel Nahhas: Lebanon is in a pre-crisis phase.” Le Commerce du Levant. January 15, 2019.

- ↩ The Lebanese state’s report on social justice in Lebanon. “Unemployment in Lebanon: Findings and recommendations.” This is an optimistic view of how many people live in poverty in Lebanon.The World Bank’s 2018 overview of Lebanon, unashamedly suggests the Lebanese economic crisis is caused by the Syrian refugees, while mentioning that the deterioration of the GDP is “driven by a higher debt service,” while “the debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to persist in an unsustainable path, at 151 percent by end-2018.” More details from Al-Akhbar’s Capital appendix.

- ↩ An old man cries in the street and speaks out about his health and economic situations, openly blaming the state. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHabm7qxjio

- ↩ The Lebanese bourgeoisie and bourgeois intelligentsia cannot understand the system in Lebanon, or it does not want to admit that the issue is actually a class and not a sect. See “How a grassroots movement toppled Lebanon’s PM,” CNN.

- ↩ Graffiti in Downtown Beirut expresses the class nature of the intifada, and in many instances revolting against Solidere, the real-estate company which took over the city’s downtown after the civil war. “If the people feels hungry, it shall eat its governors,” the Arabic version of “Eat the rich.”

- ↩ Khalil, Amal. “Burning the Nabatieh tent: we are staying here.” Al-Akhbar Newspaper, issue 3936.

- ↩ This footage shows the last (Sunday December 22, 2019) violent attacks from members of the Jumblati party on the tent of the initfada in the town of Aley. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Xn-Q-u99Fw