Costas Lapavitsas is an economist from Greece. He presently teaches Economics at the University of London and was elected as a member of the Greek Parliament for SYRIZA in January 2015. He left to form Popular Unity in August 2015, when SYRIZA signed a new bail-out with the EU and the IMF. His major works include The Left Case Against the EU (Polity Press, 2018), Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All (2013), Crisis in the Eurozone (2012), Social Foundations of Markets, Money and Credit (Routledge, 2003). Jude Kadri, is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of Ottawa. Kadri’s research focuses on the notion of “failed state”, specially when it comes to Arab states that have been dubbed as failed since the beginning of the “global war on terror.”

Lapavitsas is known for developing a Marxist approach to “financialization” as a concept that reflects the current historical period of neoliberalism (derived from the Marxist concept of Finance Capital, first extensively developed by Rudolf Hilferding). Financialization indicates the growing asymmetry between production and circulation during the last four decades. A prominent characteristic of financialization is the rise of profits accruing through financial transactions. The experience of developing countries in the era of financialization has been particularly harsh: they have been paying an implicit tribute to developed countries, mostly to the USA, the hegemonic issuer of the dollar.

Jude Kadri: Hello Dr. Lapavitsas, thank you so much for taking the time to answer some questions that relate to the current economic crisis in Lebanon. It is a very hard time for the Lebanese, possibly the worst crisis we’ve seen since the 1990s. As you have probably heard, we have an 80 billion internal debt a staggering 151 percent of GDP – (internal debt is debt owed to lenders within the country) that has accumulated at a rate of around ten percent over 30 years (and an external debt of 30 billion USD). A good chunk of Lebanon’s public debt is denominated in a foreign currency.

The banks have basically embezzled everyone’s dollars. The central bank told the banks that it wanted to buy dollars (it sold them bonds), and if offered them high interest. So, the central bank started this whole thing. The banks didn’t think twice and offered high interests to depositors (approx. 14% on Lebanese deposits and like 8% on dollar deposits – which is huge compared to other countries). The central bank pays the interest on current deposits by borrowing more from new depositors, creating a vicious cycle. There was no way that the banks were doing sufficient business and making adequate investments to give people the crazy interest rate they were promised. The banks sold lots of money to the central bank and then came a crash when dollar cash flow to the banks slowed down. With the current crisis, there has been soaring inflation, a devaluation of the Lebanese lira, the dollar peg (1507 Lebanese Lira to 1 USD) has come undone in the black market and wages dropped by a third. As a reaction to the crisis, Banks have imposed informal capital controls by shutting down withdrawals on a case-by-case basis. People are now unable to access their money.

Most of the solutions proposed by economists require cash injections thanks to the IMF. My interview focuses on the deeper understanding of the crisis in order to propose sustainable solutions.

My first question relates to current world trends. Lebanon doesn’t produce much and imports almost everything, and this seems tied to a world trend, we can see that in Greece and in Italy, how does it relate to the global phenomenon of financialization?

Costas Lapavitsas: Let’s take it one step at a time. Lebanon has got a massive current account deficit which also includes a balance of trade deficit, so clearly this means that the country imports much more than it exports and that is a measure of its loss of competitiveness. However, we need to be careful when we say that Lebanon consumes more than it produces. It is better to say that Lebanon is not competitive, has an enormous deficit on its current account, and does not generate enough saving to support investment. Its immediate problem starts to a large extent from that, but the situation is not as common across the world as you might think. Italy has a balance of trade and a current account surplus. Greece has managed to move away from a huge current account deficit (that even in the beginning wasn’t as big as that of Lebanon right now) through a deep recession and crisis. At the moment its current account is considerably smaller than that of Lebanon.

To me, the Lebanese crisis looks like, in the first instance, as a foreign exchange and international transactions crisis, a classic developing country crisis in the era of financialisation. As such it is closely connected to the country’s policy on the exchange rate. The fixed peg policy chosen by the Lebanese ruling class and operated by the central bank and the government for a long time, has proven destructive. The country’s economy is under great pressure because the strong pound has damaged Lebanese competitiveness on an international scale and facilitated the growth of domestic credit.

A fixed peg is a policy characteristic of financialization and dictated by the interests of financial capital in many developing countries. It is the preferred policy of big banks and financiers in a number of developing countries with the aim of entering the world market. Stabilising the exchange rate is closely connected to controlling inflation, and so financial capital can secure profits and take them out of the country safely, while industrial capital pays the penalty of low competitiveness. These phenomena are characteristic of subordinate (or derivative) financialisation in developing countries, reflecting the dominant role of finance capital and profit making by financial institutions. Lebanon is a severe case of subordinate financialisation and has ruined its economy by promoting financial interests.

Kadri: If Lebanon hadn’t held on so tightly to the peg, do you think it could actually be competitive considering its location in the Arab world and political reasons? Would the global market allow it to be competitive considering it’s a “developing country”?

Lapavitsas: I’m not suggesting for a minute that simply changing the exchange rate would resolve the crisis. Lebanon also has severe problems in its real economy: weak agriculture, weak industrial sector, over-expanded real estate sector, and so on. These are all difficult issues that require sustained policy intervention to be confronted, and instead of doing that Lebanese governments have made the problems worse over the years. But they are all connected in a variety of ways to the extraordinary policy of keeping the Lebanese pound pegged for such a long time.

As I have already mentioned, pegging the exchange rate is a type of policy found in many developing countries, a characteristic of financialisation because it allows foreign financial capitals to enter the country, make profits from high interest rates, and exit safely. It is also preferred by domestic financial capital because it facilitates heavy borrowing abroad at low rates, the money is then used domestically, often simply being deposited to earn high interest rates, and then making repayments abroad. It is basically finance capital and big business connected to finance that are keen to peg the domestic currency to the dollar.

Many developing countries have ostensibly adopted this policy in the years of financialization, but the severity of it in the Lebanon is astonishing. Other developing countries frequently state that they have a peg, but in practice allow their currency to slide. This helps competitiveness and exports, thus lessening the pressure on domestic industrial capital. This is a well-known phenomenon in international economics, and it happens because countries understand that the pressures from a permanently fixed peg are enormous.

Lebanon is extraordinary. It is hard to believe how stable the peg has been and over such a long time. This is clearly a reflection of the country’s domestic political and social interests. The power of the bankers, other capitalists and rich people closely connected to the banks, must be vast for that to happen. If the country continues to maintain such a hard peg and does not allow the currency to slide, it would find it much harder to confront the crisis and the impact on the domestic economy will be even more severe. It would also mean that there would probably be no real change in the domestic structures of power and the privileges of the rich would be preserved.

Kadri: Do you think that the way of living of the Lebanese pushed this peg to stay fixed? Obviously, the peg in Lebanon allowed middle class consumption of luxury goods, travel and study abroad.

Lapavitsas: I know there is a sizeable Lebanese middle class that likes the high life and spends a lot, above its means. You see evidence of their presence across Western Europe, for instance. But Lebanon is a far more complex society than simply the middle class, and there are many other powerful interests. The policy decisions have to do with the broader structure of powers in the country.

When a country enters the world market with such a peg in conditions of financialisation, loanable money capital is encouraged to move freely across its borders. The Lebanese ruling elite made this decision some time ago and crucial implications followed. The Lebanese banks emerged as a powerful agent in the economy, financed by heavy inflows of capital from abroad. For that, it was necessary to guarantee a very high return through high interest rates, and also guarantee the exit of loanable capital by fixing the peg.

An unbalanced economy was created, attracting large capital inflows from the Lebanese diaspora but also from other dollar holders cross the Arab world who aimed to make secure financial profit. The banks naturally became enormous relative to the rest of the economy, and then the central bank further complicated the picture by itself borrowing from the banks in foreign currency. The government was also able to maintain a budget deficit by obtaining some of the inflow.

The whole thing can be thought of as an enormous Ponzi scheme that can continue as long as capital inflows are sustained by people depositing dollars in Lebanese banks. Alternatively, it can be thought of as an extremely unstable mechanism allowing Lebanon to maintain a current account deficit by having a surplus on the capital account.

The high profits that the depositors made on their dollar deposits were not a reflection of real returns generated by the economy of Lebanon, or by productive activities. They derived from money deposited by new people, and the process was clearly not sustainable in the medium run. Eventually it became obvious that the country also had other obligations to meet with the incoming dollars, particularly as the current account deficit persisted. Above all, the dollars were needed to pay for imports and maturing debts. Doubts emerged about the liquidity and the solvency of banks, new depositors became reluctant to send fresh money, and the trouble started. The clearest evidence of trouble is the decline in central bank dollar reserves, a true sign of crisis. This is where Lebanon finds itself and the question is what to do?

Kadri: Lebanese Economists have argued that “we shouldn’t go the Venezuela Path”. Should we not go this path?

Lapavitsas: These two countries have very little in common, and the comparison is probably made to create fear among the Lebanese people. Their trajectories are very different and even to mention Venezuela in the context of Lebanon is misleading. I should also say that during the Greek crisis conservatives kept talking about Argentina and why Greece should not follow its so-called ‘disastrous’ path, creating a lot of confusion among the Greek people. Venezuela has a very different experience from Lebanon, partly due to mismanagement of oil production and partly due to severe U.S. sanctions.

However, from a political perspective, if the implication of warning about Venezuela is that Lebanon should not adopt an independent stance and take unilateral action, then, in this respect, the opposite is true. Lebanon needs to take unilateral action and to avoid relying on the IMF. This has clear implications about dealing with the country’s debt.

Kadri: These same economists have suggested that we need the help of the IMF. What do you think about that?

Lapavitsas: It is bad advice. There is little doubt that Lebanon is in effect bankrupt. The debt is unsustainable, the reserves of the central bank are very low, there is a Eurobond payment to make in March, and it is not clear that the dollars would be easily available. As well, the economy isn’t growing. In this situation, it would be a terrible mistake to request a sort of bail-out fund with IMF support, and then adopt its structural adjustment policies. I am sure that many people advocate this because it appears sensible and reasonable, it avoids disaster and so on. But it is probably the worst thing that Lebanon could do.

An IMF programme would focus on fiscal sustainability, it would be a program of austerity. It would compress aggregate demand in the country, probably pushing it toward recession, and would create all kinds of social problems. Not least, an IMF programme would probably not change the structure of the economy in the way that ought to be changed, that is, reducing the size of the banking sector, limiting the real estate sector, and strengthening the primary and secondary sectors. The IMF does not have a good track record in delivering such change, and there is no reason to believe that it would bring it to Lebanon.

All you have to do is look at Greece. The country had an IMF (and EU) programme from 2010 to 2018, and still operates within the parameters effectively dictated by that programme. The Greek economy hasn’t changed at all in structural terms: it has a very weak industrial sector, a very weak agrarian sector, an enormous service sector, weak productivity growth, high unemployment, and poor growth prospects. Greece is in a low-growth equilibrium, it has a kind of stability without much of a future. Lebanon can expect similar developments, if it goes down the IMF path.

Kadri: What about imposing haircuts and defaulting on debts? Do you think these practices could solve our crisis?

Lapavitsas: If Lebanon does not follow the IMF, then it has to consider defaulting and restructuring its debt. Default is a difficult issue: it’s an act of sovereignty on the part of the country, a unilateral action. The real question is what kind of default. There are always choices, as we know from the long history of national defaults. Lebanese debt is denominated in dollars and domestic currency, but the majority is in dollars. It is also owed mostly to Lebanese lenders, including banks. If the government is to default, then effectively the central bank would also have to default, and the pressure would be shifted onto the banks. Default would then probably mean a haircut on the debt, with the losses being borne by the banks. Who would bear these losses? The depositors, the lenders to the banks, the bank owners?

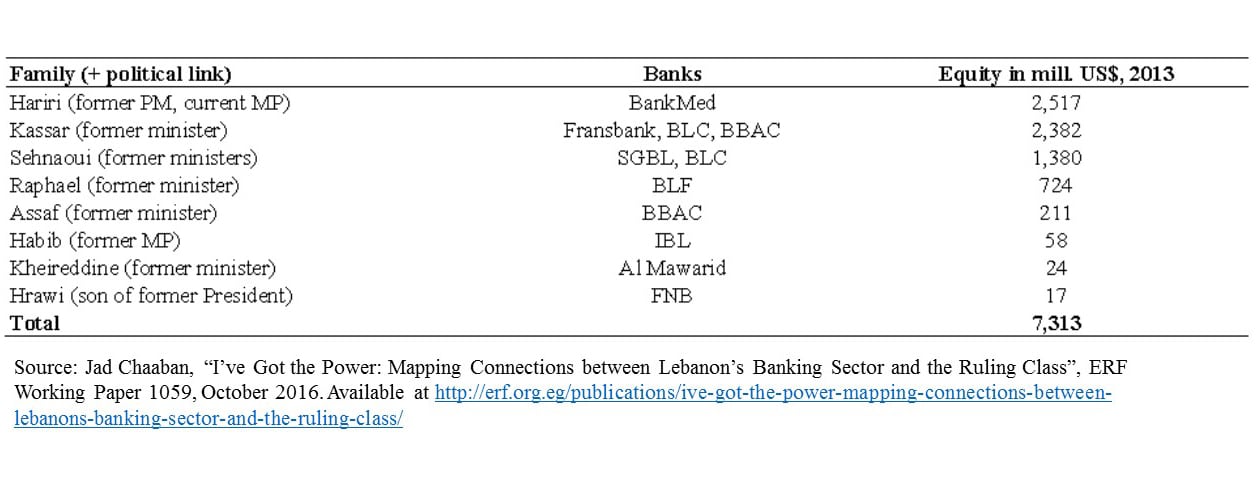

The data shows that Lebanese banks have substantial capital adequacy with high capital ratios, although I am not certain that the figures can be trusted. On this basis, the losses should fall on the owners of banks (and the holders of bank bonds) not on depositors. The assets of the Lebanese banks are four times the GDP, the capital these banks hold is substantial, and they are effectively the lenders to the government. I understand that the banks are owned by some of the richest and most influential people in Lebanon. They should carry the first and the greatest burden in relieving the debt of the country. After all, they are the people who have benefitted most from the absurd economic policies that Lebanon has followed for such a long time.

It is important in this respect also to learn from the Cypriot crisis in 2013. The problem was similar to Lebanon, with over-expansion of the banking sector, tremendously speculative financial activities, and an unbalanced economy. But Cyprus did not have a separate national debt problem and it was a member of the Eurozone, which severely restricted its room for policy. The result was to impose a haircut on deposits, which basically robbed thousands of people of their savings, without fundamentally changing the structure of the economy. Lebanon should avoid that path.

Kadri: Your last point about Lebanon is very true. Hariri owns Bankmen, and other former ministers such as Kassar, Sehnaoui, Assaf etc., own the other banks. What about the external debt, the Eurobonds, can we default?

Lapavitsas: Any country can choose how to default, this is precisely what makes default a sovereign act. The choice is not easy, but it is vital to remember that, in general, a country can far more easily restructure its internal debt. It seems logical for Lebanon to start by restructuring the dollar-denominated debt held by its own nationals, while continuing to pay the foreign lenders. The first to shoulder the costs of dealing with the country’s bankruptcy should be the domestic owners of debt, above all, the owners of banks. These banks are huge and their size and role in the economy must be reduced. One way of achieving it is to force them to carry the cost of debt restructuring. The foreigners can come after that, if necessary.

One further way of restructuring the debt, finally, is unilaterally to redenominate dollar-denominated financial assets into the domestic currency. Any debt that is under Lebanese law, could potentially be redenominated into domestic currency. That would make it easier to manage the debt as a whole, since it would lessen the pressure on the reserves of the central bank.

Kadri: The American dollar seems to have extraordinary powers, and it is tied to the American government. Do you think the Americans want to see such a crisis in Lebanon?

Lapavitsas: The USA has imposed sanctions on Lebanon as part of its policies in the Middle East, and these sanctions have complicated the crisis considerably. They’re far from helpful. But it is important not to fall into conspiratorialism exaggerating the power of the USA, though there is no doubt that American power is enormous, especially in the financial sphere. The position of Lebanon in the Arab world in undoubtedly crucial, and I suspect that a lot of the figures about capital flows in and out of Lebanon are misleading, not least in terms of flows that do not appear in the official statistics. There are probably large sums of money coming in from other parts of the Arab world, perhaps the Gulf. These flows are probably tied to Arab world politics, and the relations with the Americans. But the real questions are where are the illicit flows of money capital are coming from, who attracts them, and who manages them? One only has to look at the black market for dollars in Lebanon to realise that there are a lot of undeclared dollars, and their prices confirms the official overvaluation of the Lebanese currency.

Kadri: Do you mean illicit money that comes from illegal activities such as drug dealing or arms selling?

Lapavitsas: Who knows where it is coming from, it could be possibly money of that type. More generally, it is probably money that is not officially declared and doesn’t appear in the public accounts. Flows of this type could potentially end up in banks and complicate the official accounts. It would not surprise me if this was an important issue in Lebanon, bearing in mind that the Lebanese elite decided to turn the country into the financial hub of the Arab world.

Kadri: Can you see some similarities between Lebanon and Panama?

Lapavitsas: This doesn’t strike me as a bad analogy. Looking at the Lebanese economy as a whole, the analogy seems even more plausible. There is a large financial sector closely connected to real estate, and probably utilising financial flows that are not immediately visible. This sort of economy creates a certain social mentality and a type of class differentiation that encourages rentier behaviour and instils an outlook of easy spending. A lot of people think that money comes easy and that they only need to cut a good deal to become rich. I am not suggesting, of course, that everyone is like that in Lebanon, but a financially unbalanced economy encourages such behaviour among certain social strata. This is bad for society as a whole.

Lebanon can expect nothing good from the IMF. It is a reliable rule of thumb that developing countries should be highly suspicious of the IMF. The Fund should not be invited to interfere with domestic policies, and its advice must be treated with extreme caution.

To be fair, in the last 10 years, the IMF has become more sophisticated in the way it operates. It has, for example, acknowledged that capital controls could be necessary in certain situations. It has also acknowledged that a country’s debt could be unsustainable and therefore the lenders must accept restructuring. Only a few days ago it said so about Argentina.

However, one should never trust the IMF, despite the apparent changes, because fundamentally it does not operate in the interests of working people and does not respect national sovereignty. Indeed, its overall record is disastrous, including most recently in Argentina. The IMF will impose policies of restricting wages, cutting welfare spending, and improving competitiveness by worsening working conditions. That is how the IMF thinks and operates. It will promote austerity and liberalization, with severe negative effects on both economy and society.

Lebanon should adopt a unilateral approach and progressive forces should demand a radical set of policies, including selective default on debt and imposing the losses on the banks. It would then be up to Lebanon to develop active industrial policies to strengthen the primary and the secondary sector of its economy, and to reduce the size of the financial sector.

Kadri: Economists and politicians have argued that we absolutely need “cash injections” from the IMF to solve our crisis. They might be right that it could fix things on the surface for a short while, but I am skeptical it could fix things on the long term. What do you think?

Lapavitsas: The IMF could perhaps provide Lebanon with a “cash injection” that would boost the reserves of the central bank and allow it to make dollar payments. But a “cash injection” from the IMF would come with conditionality and structural adjustment. The IMF will ask for wage suppression, worsening labor conditions, the removal of subsidies on consumer goods, heating, welfare aid, and so on, as well as the rapid opening of the country to international competition.

The most likely thing from an IMF “cash injection” is that Lebanon will buy itself a bit of time and avoid immediate default. But the real problem of the country is to restructure its economy and reduce the dominant role of banks, The IMF will not help Lebanon put the economy on a path of growth with high employment and rising incomes. Indeed, it is likely that following an IMF “cash injection”, Lebanon will find itself in a similar position a few years down the line.

Argentina under Macri, who was elected in December 2015, adopted neoliberal policies and liberalisation. Soon the performance of the Argentine economy worsened and in 2018 the Macri government called in the IMF, which provided 57bn dollars, and asked for austerity and further liberalisation. Today Argentina is decidedly bankrupt. All that happened was that Macri bought himself a little time. Lebanon must not go that path.

Kadri: Gibran Bassil and other politicians are saying that tapping the oil reserves will solve all our problems. Do you think that’s true?

Lapavitsas: This is wishful thinking. We had a lot of similar wishful thinking in Greece. The returns from the oil and gas reserves in Mediterranean are a long time in the future, if they ever materialise. Lebanon will be bankrupt long before these funds become available. But the oil and gas reserves could prove important, if a radical restructuring of the economy took place, after dealing with the debt. In an economy that was geared toward production, with a government that was not corrupt, a society that was more open, and a polity that was democratic and defended the interests of working people, the reserves of oil and gas could provide vital. But Lebanon must resolve its crisis first.

The key thing is this: Lebanon is one of the most financialised economies in the world, a severe case of subordinate financialisation with a fix peg, free capital flows and a dominant financial sector. In effect it has ruined the productive fibre of its economy. Lebanon needs to de-financialize and develop its primary and secondary sectors. Financialization as a global trend has lost its vigour since 2007-2008, it does not have the same dynamism. There is entrenched stagnation in the productive sector of developed countries, the financial sector does not generate the same profits as in the past, there is also a global stock market bubble because of cheap money created by governments. A bizarre sort of sick capitalism prevails globally, which cannot really survive much longer. There is a limit to how far profits can be made in finance rather than in production. In this context, Lebanon needs to de-financialise and reorganize its economy in favour of working people.

Kadri: Thank you for your time!

Lapavitsas: It was a pleasure.