Dear Friends,

Greetings from the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

These are miserable times. The statistics of deprivation and death are gruesome. Far too many people struggle with hunger; roughly nine million of them dying each year from complications due to malnutrition (a child dies somewhere in the world around every ten seconds because of this).

Many of us journalists and writers have become actuaries of suffering. The general mood is despair; the general conditions of life are bare. The rhetoric of hope sounds less like inspiration and more like a rebuke. Forests burn. The wretched of the sea sink into the Mediterranean. Women’s bodies appear in the Chihuahuan Desert. Fascist thugs roam the streets of Delhi. The gap between the rhetoric of hope and the condition of despair is vast. There is no bridge between them. We live in the wound. This is a letter from that wound.

Everywhere you look, the news is startling. The keywords for the present are fairly straightforward: COVID-19, financial crisis, climate change, femicide, xenophobia, and the resilience of neo-fascist politicians and the mobs they call into the streets. No great depth is needed to be terrified by what is happening as the great wound spreads across the planet. Panic is a natural reaction, hastened by the general demise of social bonds.

The idea of social bonds or even of society is so compelling in our time. It is getting harder and harder to experience society in a civil manner: political discourse seems to have emerged from the sewers, and a general compassion for suffering seems to have evaporated as the neo-fascists propagate the hard steel of toxic machismo. This is not merely a problem of the political class–it is a problem that should be associated with the erosion of State and social institutions that would otherwise make individual lives richer. If people have a hard time getting a job, if jobs themselves are more stressful, if commute times increase, if medical care is hard to attain, if pensions deteriorate before higher expenditures (including taxes), and if it just gets harder and harder to deal with everyday life–well, then it is easy to expect tempers to fray, anger to rise, and a general social misery to be on display.

Civility is not just a matter of attitude. Civility is also a matter of resources. If we used our considerable global social treasure to ensure a decent livelihood for each other, to ensure medical and elder care, to ensure that we tackle our pressing problems in a collective way, well, then there would be the leisure time to rest amongst friends, to volunteer in our communities, to get to know one another, and to be less stressed and angry. Neither is ‘hope’ an individual feeling; it has to be produced by people doing things together, building communities, fighting for their values.

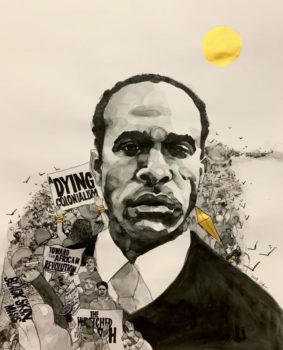

The idea of the ‘great wound’ comes to us from Frantz Fanon, who wrote in ‘The Algerian Family’ (1959) that the revolutionary intellectual must ‘look more closely at the reality of Algeria. We must not simply fly over it. We must, on the contrary, walk step by step along the great wound inflicted on the Algerian soil and the Algerian people’. Algeria was in the midst of its national liberation struggle, fighting what Fanon called a ‘hallucinatory war’ against the French. The affirmation of the value of the human from within that ‘great wound’ had been met with an avalanche of colonial violence. Our wound is equally hallucinatory, marked by ever more grim forms of violence and the enduring urgency of struggle.

From the Johannesburg (South Africa) office of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research comes Dossier no. 26–‘Frantz Fanon: The Brightness of Metal’ (March 2020). The dossier draws from Fanon’s work, as well as the work of those influenced by him who then further developed his ideas, to produce one of the best brief introductions to the work of a key thinker for our times. One of Fanon’s most pressing ideas is that the intellectual cannot simply leap into the universal and avoid the muck of everyday struggles; ‘Fanon’s life’, the dossier notes, ‘was marked by a permanent, courageous, and militant motion into the present, and into the specificity of the situations in which he found himself’. Emancipation from the wretchedness of the wound will not take place automatically, since to produce a new humanity would require what Hegel in his Phenomenology of Spirit had called ‘the seriousness, the suffering, the patience, and the labour of the negative’, in other words, for Fanon, commitment to the struggles in our place and in our time.

As Fanon famously remarked, every generation gets its project. For Fanon, that project was the national liberation struggle, which he saw as a necessary stage towards genuine internationalism. That is the reason why Fanon, born in Martinique, found it so easy to slip into the struggle of the Algerian people; he did not see the struggle in Algeria as separate from that of the entire Third World. It was as part of the Algerian delegation that he first visited Ghana in December 1958 for the All-African People’s Congress. It was in Ghana that he met Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Julius Nyerere (Tanzania), Sékou Touré (Guinea), and of course Patrice Lumumba (Congo). He attempted to mobilise support from Ghana, Guinea, and Mali to get arms into Algeria through its southern border (in September 1960, Fanon travelled along the old trade paths from Mali towards Algeria to test the route); and, when Lumumba was threatened in the Congo in August 1960, Fanon urged the members of the Congress to send an African Legion to assist the government, which was not done. There was no border to Fanon’s hope for the decolonisation of Africa, and of the entire colonised world.

When Lumumba was murdered on 17 January 1961, Fanon wrote a moving obituary for him. Why was Lumumba killed? ‘Lumumba believed in his mission’, wrote Fanon–a mission to liberate his people, to make sure that his people no longer lived in great poverty and indignity, despite the riches of the Congo. He was killed for this mission, a mission with which Fanon concurred fully. ‘If Lumumba is in the way, Lumumba disappears’, Fanon wrote. To be alive, he indicated, is to throw oneself into such a mission, to join in the struggles that lay ahead and that would create emancipation. They killed Lumumba in 1961, but ‘no one knows the name of the next Lumumba’, Fanon wrote both realistically and optimistically. The necessity of struggle would produce another movement, with its own leaders; this was inevitable. Hope exists in this inevitability.

On 5 March, at The Forge in Braamfontein–Johannesburg’s vibrant student district–Dossier no. 26 was launched at a colloquium on the philosophy and influence of Fanon. The gathering was attended by grassroots militants, trade unionists, artists, students, and academics, including figures like the eminent philosopher Mabogo P. More and the ‘Rebel Bishop’, Rubin Phillip. Leading Fanon scholars Nigel Gibson, Lewis Gordon, Michael Neocosmos, and Zikhona Valela, spoke about Fanon’s work as a teacher, clinician, and theorist. They engaged with the question of praxis from within the context of the crisis of the post-colony; their attention was focused on issues of organisation and resistance out of the great wound. In moments like this, radical hope flourishes and emancipatory ideas, forged in the vortex of struggle, take on the brightness of metal.

On 5 March, at The Forge in Braamfontein–Johannesburg’s vibrant student district–Dossier no. 26 was launched at a colloquium on the philosophy and influence of Fanon. The gathering was attended by grassroots militants, trade unionists, artists, students, and academics, including figures like the eminent philosopher Mabogo P. More and the ‘Rebel Bishop’, Rubin Phillip. Leading Fanon scholars Nigel Gibson, Lewis Gordon, Michael Neocosmos, and Zikhona Valela, spoke about Fanon’s work as a teacher, clinician, and theorist. They engaged with the question of praxis from within the context of the crisis of the post-colony; their attention was focused on issues of organisation and resistance out of the great wound. In moments like this, radical hope flourishes and emancipatory ideas, forged in the vortex of struggle, take on the brightness of metal.

Claudia Jones was born ten years before Fanon in Port of Spain (Trinidad and Tobago). Jones migrated with her parents to the United States; there, in the midst of the campaign to save the Scottsboro defendants in 1936, Jones became a Communist. A member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), Jones would be deported to the United Kingdom in 1955 (where she was instrumental in the founding of the Notting Hill Carnival). Jones travelled around the world, to the USSR and China certainly, but also to meetings of the Women’s International Democratic Federation (including to the 1952 meeting in Copenhagen).

In 1949, Jones published a landmark essay in the CPUSA’s theoretical journal Political Affairs, ‘An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman’. This essay engages directly with the question of racism and of its indignity. Several times in her essay, Jones uses the word particular. She says that there is oppression faced by any number of people, or that exploitation strikes the Black worker, but then she emphasises that the system penalises ‘particularly’ Black women workers, with ‘special severity’. This ‘special severity’ is her interest, which means that any analysis of emancipation must be marked deeply by the specific assessment of the hierarchies of oppression, and that it must attend to the specific logic of each of these layers (or ‘stratum’, as she puts it); that the ‘particularity’ of the oppression insists that not only must class be taken seriously, not only must race be taken seriously, but that gender must be at the core of the analysis and of the praxis that emerges out of it (as we acknowledge in the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Feminist Studies #1).

In 1949, Jones published a landmark essay in the CPUSA’s theoretical journal Political Affairs, ‘An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman’. This essay engages directly with the question of racism and of its indignity. Several times in her essay, Jones uses the word particular. She says that there is oppression faced by any number of people, or that exploitation strikes the Black worker, but then she emphasises that the system penalises ‘particularly’ Black women workers, with ‘special severity’. This ‘special severity’ is her interest, which means that any analysis of emancipation must be marked deeply by the specific assessment of the hierarchies of oppression, and that it must attend to the specific logic of each of these layers (or ‘stratum’, as she puts it); that the ‘particularity’ of the oppression insists that not only must class be taken seriously, not only must race be taken seriously, but that gender must be at the core of the analysis and of the praxis that emerges out of it (as we acknowledge in the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Feminist Studies #1).

With this analytical specificity, Black women around the world are, for Jones, at the vanguard of every struggle against capitalism. The specific and ‘special severity’ of the condition of Black women must be taken seriously, Jones writes, not to isolate Black women from the broader struggles; the point, she notes, is that if the cause of Black women would be ‘promoted’, then she will take her ‘rightful place’ in the ‘proletarian leadership of the national liberation movement, and by her active participation contribute to the entire American working class, whose historic mission is the achievement of a socialist America–the final and full guarantee of woman’s emancipation’. The key word here is leadership.

Reading Jones again, I imagine her meeting Fanon at one of these international meetings–perhaps in Tashkent or Beirut–and discussing their revolutionary theories; I imagine them, two radicals from the Caribbean, having a conversation about ‘slightly stretching’ Marx, as Fanon wrote in his later years. It is fitting that Fanon was buried in Algeria, and that Jones was buried to Marx’s left in Highgate Cemetery in London. Both of these remarkable intellectuals insist that intellectuals participate in the grand projects of their age, that they be specific about the particularities of oppression, and that they help us find our way out of the great wound.

Warmly,

Vijay.