Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

I admit upfront that this is a hard newsletter to read. It is about debt. There is a bloodless quality to the way that we talk about the debt of the poorer nations. There is nothing poetic here. The numbers are alienating, their outcome shocking.

In mid-April, eighteen heads of government from Africa and Europe publicly urged the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the African Development Bank, and the New Development Bank as well as other regional institutions to announce an ‘immediate moratorium on all bilateral and multilateral debt payments, both public and private, until the pandemic has passed’. Meanwhile, these agencies–and others–were asked to ‘provide liquidity for the procurement of basic commodities and essential medical supplies’.

On 30 April, Abiy Ahmed, Prime Minister of Ethiopia, wrote that the call for debt postponement is insufficient; what was needed was debt cancellation. In 2019, stunningly, sixty-four countries around the world (half of them on the African continent) spent more money to service their external debt than on health care; the governments in 121 low and middle-income countries spent 10.7% of their revenue on public health, while they drained 12.2% on external debt payments. Ethiopia, Ahmed wrote, ‘spends twice as much on paying off external debt as on health’. Last year, the IMF said that Ethiopia was one of the five fastest growing economies in the world; this is no longer going to be the case because of the impact of the novel coronavirus. Ethiopia, Ahmed noted, will slip into a coronavirus recession.

In late March, the IMF announced that it would provide a new facility worth $1 trillion to prevent countries from falling into a coronavirus recession (under pressure from the U.S. Treasury, the IMF excluded Venezuela). Within a short period of time, more than a hundred countries appealed to the IMF for help. The IMF and the G20 either cancelled debt payments for the next six months or froze debts for the remainder of the year. The G20 said that $32 billion in debt servicing owed to official, private, and multilateral creditors would be suspended in 76 countries. The current debt stocks of the developing countries–by comparison–is over $8 trillion. The absence of any international debt authority means that these initiatives are insufficient. Private creditors are not bound to following through with these initiatives, which means that many of the highly indebted countries will have to continue to service their debt to them. There is talk of the creation of a ‘central credit facility’ developed within the World Bank, where the indebted countries could deposit their debt and let the World Bank deal with the creditors; after the coronavirus has gone, the situation of the debt would be reassessed.

Far more ambitious is the proposal from the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) to establish an International Developing Country Debt Authority. This body would have a dual mandate: first, to oversee any temporary standstills in debt repayments in order to stave off such events as a coronavirus recession; second, to look carefully at the necessity of fundamental debt relief (including debt cancellation). UNCTAD has made similar proposals in 1986, 1998, 2001, and 2015; each time the powerful creditors and the wealthy nations have rejected this approach. In 1985, the Cuban government hosted the Havana Debt Conference, where Fidel Castro made a plea for a Third World Debt Strike to put pressure on the creditors to come to the table; immense pressure on the less confident states derailed that approach. Neither UNCTAD nor the Havana Debt Conference were able to move this agenda. It now returns to the table.

On April 16, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said bluntly that the U.S. is against any of these more aggressive measures. The most that the U.S. would accept was ‘time-bound suspension of debt service payments’ in the G20 and Paris Club (official creditors), while the London Club (private creditors) would be asked to act on a voluntary basis. Not only has the U.S. put its foot down to prevent any proper immediate relief, but it has said that no long-term debt cancellation is going to be allowed. If there is a coronavirus recession in the countries of the Global South, then so be it.

One of the countries that will slip into a coronavirus recession is Jamaica, where Minister of Finance and Public Service Nigel Clarke said that the ‘tourism sector is operating at zero utilisation and the prospect and timing of reopening remain unclear’. In November 2019, Jamaica completed its obligations to an IMF loan; the head of the IMF team, Uma Ramakrishnan, said that Jamaica was poised for a bright future. But these friendly words came at the end of a process of terrible austerity on the island.

Christophe Simpson, Chair of Jamaica Lands, spoke to Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research about the situation of debt and health care in Jamaica. Simpson emphasises that, in Jamaica, 90% of the population is descended from people who had been enslaved, whose labour was stolen by the British. When the people won their freedom, the British exchequer compensated the plantation owners for the ‘loss’ of their ‘property’; the loan that the British government took to pay the plantation owners was not paid off till 2015, when British Prime Minister David Cameron came to Jamaica to say that reparations for the formerly enslaved people and their descendants was off the table. Colonialism left Jamaica reliant upon tourism, with limited economic sovereignty.

‘We are in a never-ending cycle of debt’, Simpson said. ‘International institutions like the IMF set conditions on the money they lend, so that–for instance–we are not allowed to spend more than 9% of our GDP on public sector wages’. Health care and education face cuts, which means that nurses and teachers are underpaid. ‘Nurses and teachers are lured away from Jamaica by promises of higher wages in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Britain’. ‘They essentially benefit from our indebtedness’, Simpson explained. Jamaica’s people provide each other with free primary and secondary education and with half of the tertiary education costs; 80% of tertiary graduates leave the island to work abroad. Jamaica, which has been robbed for centuries now subsidises the health care sectors in the North Atlantic states.

Elean Thomas (1947-2004), a founder of Jamaica’s Workers Party, in her book Before They Can Speak of Flowers: Word Rhythms (1988) thought about how often she had been asked not to interfere in politics, or–as she put it in the clever Jamaican variation–in politricks. Neither hunger nor ill-health have to do with anything other than politics, since it is through political decisions that resources are stolen from people who then suffer the indignities of poverty.

Elean Thomas (1947-2004), a founder of Jamaica’s Workers Party, in her book Before They Can Speak of Flowers: Word Rhythms (1988) thought about how often she had been asked not to interfere in politics, or–as she put it in the clever Jamaican variation–in politricks. Neither hunger nor ill-health have to do with anything other than politics, since it is through political decisions that resources are stolen from people who then suffer the indignities of poverty.

How I fe no deal with politics?

when Politricks a deal with me.Take for instance…

the good book says

‘By the sweat of your brow

you shall eat bread’But don’t you know

whole heap of people

a sweat rivers

every day

and still can’t find no bread

to eat?Politricks

is what decide that.

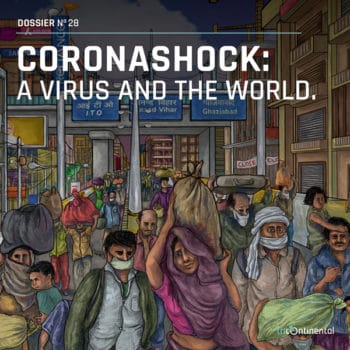

Our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Dossier no. 28 (May 2020) on CoronaShock: A Virus and The World is focused on the politics–or the politricks–of the moment. The virus of austerity and of enforced debt servitude produced a fragile world order in most of the world, which has crumbled in the wake of the global pandemic. The dossier traverses the political framework of neoliberalism, which has eroded the basic social institutions that provide health care and education, creating a world in which unproductive finance rules the roost and in which the vast platform or web-based firms have taken hold of a large part of the economy.

Along with the International People’s Assembly, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research produced a 16-point declaration that includes immediate relief and long-term measures. In our most recent dossier, we look carefully at one of these policies, the call for a Universal Basic Income (UBI). We lay out our critical view of the UBI scheme, offering our assessment of why this must be an undiluted universal scheme and why it must be funded by taxes on the wealthy and on profits rather than merely by dismantling other social service schemes. We take a socialist approach to the UBI, insisting that it be a supplement to other social wages rather than perpetuate the myth of the ‘deserving poor’ to sift out who should qualify and who should not.

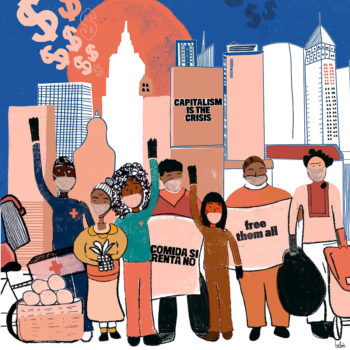

Dossier no. 28 is illustrated by eight artists from Cuba to Malaysia who came together to make images that depict the Great Lockdown. This newsletter shares some of their work.

A call for artists for Anti-Imperialist Poster Exhibitions.

Collaboration with artists is a central feature of our work. For that reason, we have partnered with the International People’s Assembly and the International Week of Anti-Imperialist Struggle to hold a poster exhibition featuring four different concepts–capitalism, neoliberalism, hybrid war, and imperialism. Please widely forward the call for this exhibition.

Three AP photographers–Dar Yasin, Mukhtar Khan, and Channi Anand–won a Pulitzer Prize for their photography on the struggles inside Kashmir. Please see our Red Alert on Kashmir.

Warmly, Vijay.