June 5, 2020 — Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal reposted from MR Online.

Jack Mundey’s passing was met with great sadness, tempered with the knowledge that his legacy will never die. Fifty years ago, Jack and his comrades recast the corrupt and ineffectual New South Wales branch of the Builders Labourers’ Federation1 (BLF) into a fighting democratic organisation and were probably the world’s first ecosocialist union activists. According to the German Green Party founder Petra Kelly, use of the word “green” as a synonym for environmental politics stems from the BLF’s policy of “green banning” ugly, anti-social and polluting urban development.2 Blacklisted after the union was crushed by an unholy alliance of the state, corrupt politicians, property developers and sectarian union opponents, Jack continued as an environmental activist until the end of his days. He is survived by his life partner, Judy, herself a lifelong left-wing activist.

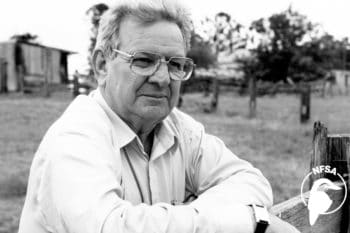

Image credit: “Jack Mundey: Unionist and Environmentalist,” National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (via the film website Kanopy).

John Bernard “Jack” Mundey was born into a poor Irish-Australian Catholic farming family during the Great Depression. Growing up surrounded by the extraordinary beauty of the Atherton Tableland’s rainforests, he gained respect and appreciation of nature. Although he never went hungry, many of his white classmates did and the dire poverty of the Aboriginal people was everywhere apparent. When he was a young man, Jack travelled south to Sydney, where he worked in a sheet-metal factory and joined the Federated Ironworkers’ Association. He also played Rugby League football for Parramatta for several seasons. Somewhere along the way in the 1950s, he lost his Catholic faith, joined the Communist Party of Australia (CPA), and started working as a builder’s labourer—or BL as they are known in Australia—at the party’s urging.

At the time, Australian unions were much stronger than they are today, with a unionisation rate of around 60 percent of the workforce. The members of militant unions such as the Waterside Workers’ Federation were hardened in class struggle against hard-fisted employers and their government friends. Other unions were much less radical and often bureaucratised. The NSW BLF was one of the worst. Weak and ineffectual, it was led by gangsters and “defrocked” lawyers who often sided with the bosses when they could be bothered to visit jobsites. Sanitary and lunch-room facilities were primitive if they existed. Job safety was appalling, and first aid officers were unheard of. Wages were a fraction of those paid to the members of craft unions in the industry. BLs were on hourly hire, never knowing when their services would be terminated. It was not unusual for bosses to fire workers just before Christmas to avoid holiday pay. Workers might be laid off for one reason or another, then rehired the following day or week. Labourers were hired for the duration of a project and then had to search for further work. If the weather proved inclement enough to stop work, the labourers were laid off without pay, but had to be on call. Things could be worse, however, for the practice of “body hire” was widespread. Men hopeful of work would line up on the sidewalk and the bosses would come past and pick who they wanted for an hour or a day’s work. There was no sick or holiday pay. Naturally, the bosses kept a blacklist and in this they were assisted by the gangster officials, who grew fat on the members’ dues. In one notorious incident, the NSW BLF secretary drove 300 miles to the Snowy Mountains hydroelectric scheme and recruited large numbers of workers who spoke little English who were doing jobs over which the BLF had no coverage. He then squandered the money in an extended alcoholic binge, and never showed his face again on the scheme. In the prevailing atmosphere of the Cold War, the crook’s anti-communism made him many friends in high places.

The BLF’s members performed much of the hardest, dirtiest work in the industry, including pick and shovel labour, barrowing and placing concrete and carrying heavy loads. They were often despised by bosses, skilled workers and much of so-called “public opinion”. The writer once overheard a manager laughingly instruct a site foreman to “work those fucking labourers until the shit runs out their arses.” To him, BLs were scum—equivalent of the biblical ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’—and there was a strong dash of racism in his contempt. To many, including some building craftsmen, BLs were “shit-labourers”. Sadly, some accepted the label. In the years after World War II, millions of immigrants poured into Australia, many of them from southern and eastern Europe. If they had imagined Australia as a land of milk and honey, with the streets paved with gold, they were soon disabused. Immigrants did the dirty, hard, and dangerous jobs that the ‘native born’ were often reluctant to do, and this included the heavy and dangerous—and least remunerated—jobs in building and construction. All too often, they were derided as “wogs” or abused with other racist epithets. By the 1960s, around 70 per cent of the NSW BLF’s members were foreign-born.3 Many spoke little English and were given little opportunity to learn and thus could not participate in union activities, which suited the corrupt officials fine. With dozens of languages spoken, it was also difficult for honest unionists to organise to oppose gangster rule. The situation was a kind of utopia for the bosses—and one which many today have gone back to with the “gig economy”.

By the late 1950s, many high-rise buildings were under construction in Sydney’s central business district, and the trend continued into subsequent decades, completely transforming the city from low rise to skyscrapers. The effects of the high-rise boom on the work were contradictory. On one hand, the boom increased the dangers the workers faced on the job, but on the other it led to an explosion of skills enhancement for those outside of the craft unions. The hard “grunt” work continued but increasing numbers of BLF members worked in jobs which needed skills commensurate with the members of the craft unions. Such BLF members included riggers, scaffolders, dogmen, and powder monkeys, or explosives experts. Personally, I will never forget the advice of an older leading hand rigger when I was working with him as a young assistant rigger “plumbing up” structural steelwork. “I regard myself as equal to any tradesman,” he said, and he was correct.

The skyscraper boom had significant dangers for the BLF’s members. The construction employers were motivated above all by the desire to maximise profits. They were often happy to sacrifice safety to speed up production and in an intrinsically dangerous industry this could not but lead to high rates of death and injury. Building skyscrapers meant working at perilous altitudes, often in artificially created winds, and in one 12-month period in the 1960s, 14 dogmen4 died on the job in Sydney. Dogmen slung loads and directed cranes, but there was an added, very dangerous dimension to the work. Former Sydney dogman Kevin Cooke said this about the job:

Do you know what dogmen used to do? You were riding the loads all the way down the buildings. The crane driver was on the top, but he couldn’t see you all the time. He could only see the wire going over the edge. You could signal him with a rope that ran back up along the wire to a bell on the crane, but that was all you had. Some of the old blokes used to paint a line on the wire, and then they could see where you were supposed to be. They dropped one of the kibbles, that’s the cement holder, on top of a double decker bus doing that one day! So, the dogmen were ridin’ around on the hooks and the slings – and the slings were only as thick as your finger!5

The bell rope Cooke refers to could get tangled up with the load and the slings with fatal consequences.6 The solution to such a dangerous job was to employ two dogmen, one on top and one below, but the bosses were opposed because it meant double the wages. The union—which meant the dogmen themselves—eventually refused to work without two dogmen to a tower crane. This, of course, was after the corrupt officials were cleaned out. Riggers, who sometimes also rode the hook, had little in the way of safety equipment, and practices such as slinging multiple pieces of steelwork on crane hooks and working high above the ground on wet girders on in wind were fraught with danger.

The higher buildings rose into the sky, too, the deeper their foundations had to be dug, and this brought fresh perils for BLs employed in excavation work. Sydney sits on a belt of hard sandstone, and this had to be cut, drilled, and blasted for the foundations. Such work exposed the labourers to danger of cave-ins and to clouds of crystalline dust. As a result almost 250 Sydney excavation workers died from silicosis between 1948 and the 1960s, and many more contracted silicosis, a dreadful lung disease akin to miners’ pneumoconiosis.7 As Pete Thomas wrote, in three years in the 1960s, there was “an appalling total of over 61,000 compensation cases—some fatal, others creating permanent disabilities, others lesser but still cruel—…in NSW building construction and maintenance.” In one year in the early 1970s, 44 building workers died in NSW.8 The militants had a hard battle to “tame the concrete jungle”. As far as the bosses were concerned, BLs were a dime a dozen and easily replaced.

This, then, was the industry that Jack Mundey entered as a young man in the mid-1950s. It was a harsh, tough, and perilous working environment, and the union officials were not afraid to set goons to bash dissidents. Together with like-minded workers, many of them members of the Communist Party or left-wing Labor Party members such as Mick McNamara, Jack worked to organise the rank-and-file to oust the gangsters and build a democratic union. The union’s meetings—when they were called at all—were chaotic affairs. One organiser was infamous for turning out the lights so that goons could bash the militants! Ballots were rigged as a matter of course. But the militant caucus worked doggedly, meeting in pubs down near Circular Quay in the shadow of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, producing newsletters, gaining shop stewards’ positions, and winning over most of the membership. However, although the gangsters were removed from office in 1961, their immediate successors, although honest, faced enormous problems and lacked the dynamism of their successors. Seven years later, in 1968, Jack Mundey was elected secretary of the union. Like many other new officials, Jack was a member of the CPA, but new BLF president, Bob Pringle, was a member of the Australian Labor Party (ALP). The ALP leaders forbade “unity tickets” but left-wing members often ignored the directive, and Pringle took an active role in transforming the union into a fighting, democratic organisation.

Like many BLs, the new leadership resented the image of BLs as “shit-labourers” and were well-aware of the rapid advancement of their members’ skills. Part of organising for higher pay was fighting for recognition of BLs’ worth and for their human dignity. The long-downtrodden BLs had found a new solidarity and dignity. One old militant recalled that before the left’s takeover of the union, builders’ labourers would, if questioned about their occupation, reply self-deprecatingly, “Oh, I’m just a labourer”. Afterwards, they would answer proudly, “I’m a bloody BL!”9 Joe Owens, the British migrant who succeeded Mundey as secretary, made this clear in the documentary film “Rocking the Foundations”, insisting that “We are not just animals who put things up or tear them down.”10 They realised, too, that the new skills and construction techniques gave the union a great deal more industrial clout than previously. Dogmen, to give one example, could bring work rapidly to a standstill should they close to do so.

In 1970, the union began a campaign of militant strikes to lift BLs’ pay. Employing mass, flying pickets, they rapidly shut down the industry. After five weeks, the employers capitulated, granted large pay raises. Most importantly, for the first time, BLs’ wages reflected their skills and indispensability. A new scale set their wages at a minimum of 90 percent of those paid to craftsmen such as carpenters and bricklayers, with the most highly skilled BLs receiving near parity or even exceeding tradesmen’s pay. At the same time, the BLF experimented with the ideas of workers’ control, occupying construction sites, electing their own foremen, staging sit-ins and “working in” in response to lockouts, poor safety conditions and sackings.

What was happening on Sydney’s building sites reflected the rise of radical social movements at that time, in large part a response to the imperialist war in Vietnam. In 1963, the right-wing Australian government sent combat troops to help the corrupt Saigon regime and had introduced conscription of 19-year-old males as cannon fodder. By 1970, hundreds of thousands of Australians had taken to the streets to protest the war, many young men refused to serve, significant numbers of unionists took strike action, and there were countless sit-ins and other forms of resistance. The same period saw the rise of women’s and black liberation, strikes by Aboriginal stockmen, and the emergence of the gay liberation movement.

Jack Mundey and others in his union threw themselves wholeheartedly into this radical ferment. Bob Pringle and fellow BL John Phillips were arrested in 1972 for cutting down the goalposts at the Sydney Cricket Ground to try to stop a rugby match with the racially segregated South African Springboks. Prior to the tour, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) had urged union affiliates take whatever action is necessary as an act of conscience to obstruct the tour.11 Left-wing Australian unions have a long history of political and social involvement. During World War I, they led the fight against conscription. In 1938, dockers, known as wharfies in Australia, refused to load scrap steel aboard the SS “Dalfram”, bound for Japan, because it would be used in bombs and bullets for Japanese aggression against the Chinese people. After the war, wharfies and seamen successfully black-banning Dutch shipping in Australian ports in solidarity with the Indonesian freedom struggle. After the Australian government committed troops to support the U.S. in Vietnam in 1964, the maritime unions refused to load or sail any vessels to Indochina.

Both in response to the radical mood and as an initiator of it, a left tendency had emerged in the CPA, and Mundey and his party comrades in the BLF were an important component of this. The CPA had been slavishly pro-Moscow up to the mid-1960s (with an equally slavish pro-China wing breaking off in 1963 to form the CPA-ML). The depth of the break was shown in 1968 when the CPA condemned the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact powers and pledged its support for the ideas of “socialism with a human face”.12 Mundey gives credit to the radical shift in CPA policies: “I’m sure.” He wrote, “that none of our innovations would have been possible except for the changes in the Communist Party of Australia, even though we went beyond the CPA mainstream”.13 Taking the ideas of the new movement for women’s liberation into the workplace, the BLF encouraged women to apply for jobs, and when the boss on the Summit skyscraper site refused, the female applicants “worked-in” with the support of the male BLs and won. In 1973, Denise Bishop was elected to the union executive and became possibly the world’s first female construction union organiser. There had always been a few Aboriginal BLs, including the dogmen Kevin Cook and Lance Shelton. The BLF was determined to end the situation in which Aboriginal people were “seen and not heard”. Indeed, not so long before, some unions had barred Aborigines from membership and tolerated unequal pay. The BLF appointed Cook and others as organisers in what was perhaps another “first”. As we have seen, the BLF’s membership was overwhelmingly overseas born, yet immigrants had long been treated as second class citizens, both in the union and in the industry as a whole.14 The BLF appointed bilingual organisers, gave them a place on the union executive, and ensured that the proceedings at all meetings were translated into languages including Greek, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and Serbo-Croatian.

Under Mundey’s leadership, the NSW BLF was taking a radical course that would take far beyond anything ever attempted elsewhere in Australia, or indeed in the whole world. That course would see the union black ban millions of dollars’ worth of unsightly and environmentally unjustifiable development—and it would do so with the support of the membership. Indeed, any of the “green bans” the union imposed had to be agreed to by a democratic majority vote of the members at mass meetings. Furthermore, the union was able to take the course it did because it was profoundly democratic and because the leadership had been able to lead the formerly despised labourers in successful battles to “tame the concrete jungle”, win vastly improved wages and conditions, and give them a sense of their worth as human beings. As U.S. workers know too well, many unions are oligarchic organisations led by entrenched officials wedded to the idea of business unionism. It was the same in Australia. The NSW BLF, on the other hand, abhorred ingrained bureaucracy and worked hard to ensure that control of the union stayed in the members’ hands. The leadership could not unilaterally decide on actions, or to call them off. All major decisions and policies could only be decided on by mass meetings of the members. Contrary to the usual Australian union custom of officials keeping the same hours as the employers, in the BLF all officials kept the same hours as the workers on the job. Other union officials paraded in suits and shared meals with the bosses. Not so in the BLF. “The only time I eat the boss’s lunch is when I steal it,” said one organiser after a sit-in in the site offices of a major builder. Although other officials enjoyed high salaries and perks, their BLF counterparts were paid the same wage as the members. In a move that shocked Australian labour skates, the BLF introduced limited tenure of office: after a maximum of six years in a paid position, officials had to go back and work in the industry. Mundey says that the policy “broke down the barrier between officials and workers”.15 The trust earned by such measures, and by the union’s successes in winning vastly improved wages and conditions, allowed it to carry out actions way beyond anything achieved anywhere in the world since that time. Mundey himself stated that “If it wasn’t for that civilising of the building industry in the campaigns of 1970 and 1971, well then I’m sure we wouldn’t have had the luxury of the membership going along with us in what was considered by some as ‘avant-garde’, ‘way-out’ actions of supporting mainly middle-class people in environmental actions. I think that gave us the mandate to allow us to go into uncharted waters.”16 Ominously, one of the most vociferous critics of this kind of action was the union’s federal secretary, Norm Gallagher, a member of the Maoist Communist Party of Australia, Marxist- Leninist; a sectarian, ultra-Stalinist opponent of the CPA.

Like its sister parties round the world, the CPA had little or no record of environmental activism. The writings of Marx and Engels on ecology had been forgotten, despite Progress Publishers in Moscow keeping books such as Frederick Engels’ Dialectics of Nature in print. Many sections of the Australian left and labour movement, including some self-styled revolutionaries and Communists, depicted the green bans as a “diversion from the class struggle” and a capitulation to alien “middle class ideas”. Norm Gallagher attacked support for the NSW BLF as coming only from “residents, sheilas and poofters”,17 although to be fair he did impose a limited number of similar bans in Melbourne. The ecological ideas that emerged in the 1960s with the publication of such books as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring,18 contrasted with a world-view that viewed nature as a hostile enemy to be subdued, or mastered, and which was expressed in an ideology of limitless economic growth. Such views, it should be stressed, collide with classical Marxist ideas of the place of humanity in nature and succumb to the logic of capitalism, whose raison d’être is the endless reproduction of capital. The impetus behind the green bans was not un-Marxist at all, and Mundey and his comrades were pioneers of what we now call ecosocialism. Their premise was, as Mundey put it, “It is no point winning great wages and conditions if the world we build chokes us to death”.

An intensely thoughtful man, Mundey closely observed the rapid changes taking place from the 1960s in his adopted city, and he didn’t like much of what he saw. As in Marshall Berman’s New York, it was a case of “all that is solid melts into air.”19 Mundey was no nostalgic reactionary, yearning for a supposedly golden past, but neither did he like seeing the social space of his city reshaped by and for the benefit alone of developers seeking investment opportunities for vast amounts of capital generated by Australia’s mining boom. Enormous profits were made as old buildings and precincts were razed to make way for skyscrapers, and land prices soared astronomically. With the connivance of governments and with lax planning regulations, much of the cityscape that was of historic, architectural, and social value was ripped down in a frenzy of speculation. Graceful Georgian terraces fashioned from the honey-coloured Sydney sandstone, “Victorian spires and domes, parkland, [and] jewels of art deco all fell to the wrecker’s ball. Scab labour would be used in nocturnal operations to pull down heritage-listed buildings. This was capitalism in the raw,20 powered purely by the greed for profit. Sydney’s inner suburbs had always had a large, mainly working-class population, and they too were destroyed to make way for the new development. Tight-knit communities, which had weathered wars and depressions, fell victim to the developers’ relentless assault. Unable to afford the huge rents charged for new inner-city housing, the working-class residents were dispersed to the city’s far-flung suburban fringes. Ironically, the exodus included many of the building workers who were tearing down the old cityscape and throwing up the new skyscrapers. Jack Mundey asked “What is the use of higher wages alone, if we have to live in cities devoid of parks, denuded of trees, in an atmosphere poisoned by pollution and vibrating with the noise of hundreds of thousands of units of private transport?”21

Traditional, “bread and butter” unionists may have privately lamented the onslaught but bowed to the relentless march of what they were told was “progress”. Mundey, however, realised that his militant, well-organised union had the power to put a spoke in the developers’ wheel. The union’s membership had soared from 4000 to 11,000 because of the boom and an intensive recruiting drive.22 They could take on the developers and their government facilitators at the point of production—and destruction. It was never a matter of opposing all development, but of challenging the well-nigh hegemonic assumption that the developers’ interests were synonymous with those of the city’s inhabitants and the urban environment. The developers’ own “turf” would become the site of class struggle, but of class struggle with a new ecological dimension. The green bans movement was born.

In 1971, the BLF banned work on a new private housing development at Kelly’s Bush on the north shore of Sydney Harbour. The BLF acted in concert with the FEDFA, a smaller sister union led by another CPA member, Jack Cambourne, that organised bulldozer and crane drivers.23 Kelly’s Bush, which the AV Jennings group wished to obliterate, was the last remaining piece of natural bushland on the harbour. The local middle-class residents had unsuccessfully lobbied members of parliament and other people of influence to halt the development, but the conservative NSW state government strongly supported AV Jennings. It seemed that Kelly’s Bush was doomed, but in desperation, the residents’ committee stumbled on the idea of asking the unions to halt the project. Fortuitously, they wrote to the BLF, which dispatched Bob Pringle to speak with them. The meeting was a study in contrasts. Pringle was a tough ex-seaman, who had come ashore and worked as a rigger on the city’s high-rise buildings. The residents were mainly middle-class, respectable women who probably had voted conservative all their adult lives. Pringle, however, was impressed by their case and recommended that the union black ban the development and call on the FEDFA for support. The BLF, however, was a super-democratic union. The executive could not and did not wish to impose the ban, which would after all affect jobs, without putting it to the members for ratification. Accordingly, the officials called a mass meeting of members, which voted overwhelmingly to “black ban” the project. The FEDFA followed suit and the bushland was saved—and indeed remains so to this day. Other bans quickly followed and somewhere along the road, a union member or supporter coined the term “green ban” to describe union action to save natural bushland and parks. The term was expanded to describe bans to save historic urban precincts and significant buildings.

The Kelly’s Bush ban was stridently criticised by leftists, who saw it as a diversion from the class struggle, and by conservative unionists who believed that unions should restrict themselves to “pure and simple” unionism. Such crudely economist views had nothing to do with the profoundly ecological essence of Marxism that Mundey and his comrades had re-discovered. The union would respond to any genuine request for help, and if the members agreed, would place a green ban on the offending project. In any case, preserving bushland was in the interests of all Sydneysiders, including the city’s working-class and in fact, it was often working-class homes and precincts that were saved from the developers.

The Kelly’s Bush ban was imposed without a major push-back from the developers or the authorities. Perhaps they were dumbfounded by what they would have seen as the brazen effrontery of the BLF and the FEDFA. Perhaps also, they worried that the sight of cops attacking “doctors’ wives” would alienate government voters. The authorities were not so gentle with BLs and their supporters in subsequent green bans. The most celebrated ban of all was that imposed on the Rocks precinct just west of Circular Quay at the southern end the iconic Sydney Harbour Bridge. The ban was largely successful, but it was accompanied by hard struggle. As I have written elsewhere, the Rocks is

Australia’s oldest urban precinct, dating from the 1790s. It is the site of many significant buildings and was also the home of a close-knit working-class community who lived in rows of terraced houses, often at controlled rents. In 1972, the state government unveiled a master plan for the redevelopment of the suburb. The people would be evicted, and their homes destroyed. In their place would rise a grotesque $2000 million24 commercial skyscraper development owned by wealthy corporate interests. Had the government got its way, a community would have been killed, together with the collective memory of over 160 years, along with one of Australia’s most beautiful urban areas.25

Horrified by the plans of the government and developers, Rocks residents had already formed an action group to fight the proposals. Inspired by the success of the Kelly’s Bush campaign, they too turned to the BLF and FEDFA for support. Mass meetings endorsed their plea and bans were duly imposed. This time, the authorities were prepared and sent in scab labour and the police to protect them. The union and residents imposed mass pickets, occupied buildings due for demolition, and staged protest marches through the central city. Many BLs and residents were arrested, including Jack Mundey, but they did not give up and in the end the authorities had to negotiate. The residents agreed to some redevelopment, but the essence of the precinct was saved. A later, more progressive city council renamed one of the streets Jack Mundey Place.

The Rocks green ban was followed by many others, including at the beautiful Centennial Park in the city’s eastern suburbs and the Botanical Gardens near Circular Quay. The latter ban stopped the AMP insurance company from digging an underground car park, which would have meant the immediate destruction of several giant Moreton Bay fig trees. Next, green bans prevented the demolition of a host of historic buildings, including the Theatre Royal and the Pitt Street Congregational Church, which would have been replaced by a multi-storey carpark. Bans also prevented the demolition of thousands of houses along the planned routes of the Eastern Expressway and the Western Distributor, and stopped the hideous redevelopment of the inner harbour-front suburb of Woolloomooloo, widely celebrated as “the most Sydney-like place in Sydney”.

By 1973, the state government and the developers were determined to stop a movement that had imposed some three dozen green bans at a cost to the developers of $3000 million—or roughly A$36,000 million in today’s values.26 Formerly peaceful Victoria Street in Woolloomooloo became a bloody battleground as the police and developers’ goons waded in the crack picketers’ heads and drag out residents and supporters staging sit-downs in buildings slated for demolition. A prominent supporter of the bans, Juanita Nielsen, disappeared and although it is an open secret that she was murdered and dismembered by the developers’ thugs, the case has never been solved. At the time, the NSW police force was riddled with corruption and worked hand-in-glove with the developers and the sleazy NSW Premier, Robin Askin, who was later exposed as a crook with interests in illegal casinos and the recipient of huge bribes. The “respectable” bourgeoisie rushed to support these gangsters. In one 12-day period in 1972, the Sydney Morning Herald—“granny” to Sydneysiders—published five editorials fulminating against “a handful of unionists led by the nose by a member of a party dedicated to social disruption and the overthrow of democratic government…” Askin tub-thumped about the BLF as “traitors to this country” and made hysterical forecasts of the union causing “rioting and bloodshed in the streets of Sydney”.27 Any rioting and bloodshed was orchestrated by Askin, the police, and the developers and their goons.

In 1973, the BLF again made history when the members voted to ban work on a hall of residence at Macquarie University in the northern suburbs. The dean of the Robert Menzies College had expelled a student, Jeremy Fisher, for being gay. The Anglican dean believed that Fisher’s sexuality was due to him being “possessed” by a Chinese mask owned by his parents. The university’s Student Representative Council, which was controlled by leftists, demanded Fisher’s reinstatement, but the dean refused, with the full support of the vice chancellor and the university council. The SRC turned to the BLF for help, noting that building works were underway at the College. Astoundingly for the time, when homosexuality was criminalised and homophobia was deep-seated in Australian culture, a mass meeting of BLs working on projects at the university voted to ban work on the College site. When the university authorities refused to budge, they black banned work on all the many projects under construction at the university.

The authorities surrendered and the action is remembered as the first “pink ban” in world history. The labourers’ actions were decades ahead of the times, but not all observers were impressed with it, or with the green bans as a whole. The right-wing Federal government was moving to deregister the federal and state union’s right to represent its members in the Arbitration Commission. In the Australian industrial relations system, the Commission adjudicated and ruled in disputes between employers and unions. Although the NSW BLF preferred to negotiate directly with employers, it did make use of the Commission on a tactical basis.

Another person who viewed the pink ban with hostility was Norm Gallagher, the BLF’s federal and Victorian secretary. Gallagher was a Stalinist hardliner and a confirmed homophobe who hated the “revisionist” CPA and believed the NSW BLF’s actions might prevent him from gaining a position on the ACTU executive. For his own reasons, Gallagher was preparing to join with the employers and the right-wing NSW and federal governments to crush the NSW BLF. In 1974, Gallagher decided to set up a rival “official” BLF branch in NSW and replace the Mundey branch officers with pliant apparatchiks. Accordingly, Gallagher descended on Sydney with a horde of scabs to replace NSW Branch BLs. The operation was bankrolled by the Master Builders Association (MBA), and the Askin government offered Gallagher every assistance to break the NSW branch. NSW branch organisers were barred from all sites and BLs who refused to join the new branch were fired. When FEDFA crane drivers went on strike to support the NSW BLF, Gallagher flew in scabs to replace them and there was a steady trickle of interstate “conscript” workers” encouraged to take over the jobs of Mundey loyalists. Gallagher and the employers also used the services of gun thugs to intimidate honest BLs. These types were housed in luxurious motels at rates far beyond the means of ordinary BLs, with the bosses picking up the tab. When challenged to put his case to a mass meeting of BLs, Gallagher declined, claiming that it would be “full of residents and poofters”.

The final blow came in March 1975 when the NSW branch office in the Sydney Trades Hall was burgled and its records stolen by a career criminal on contract to Gallagher and the bosses. Shortly afterwards, the NSW leadership advised its members to take out membership of the Gallagher branch and continue the fight from within. With heavy hearts, they agreed at a final mass meeting. Most of the NSW leadership was blacklisted and never worked in the industry again. Later, regretting what he had done, federal president Les Robinson admitted, “I think we destroyed a virile organization and it didn’t do the federation any good either”.28 Ironically, ten years later, the Gallagherites were themselves crushed by governments and employers, with the help of rival unionists. Gallagher served a prison term for accepting secret commissions from employers and rival unions absorbed the BLF.

As I have written elsewhere,

The NSW BLF perished, but its exploits have become the stuff of legend and an inspiration to all who wish to rebuild the workers’ movement as a democratic, class-conscious movement, committed to social and environmental action as an integral part of the aim of building a better world. Since those rare old times, other unions have from time to time taken up ecological issues, although perhaps none with the sheer panache and militancy of the NSW BLF. During the late 1970s and early ’80s the ACTU banned the mining and export of uranium “yellowcake”, until officials linked to the right-wing Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke undermined the policy from within. On occasions, wharfies have banned ships carrying cargoes of scarce rainforest timbers from Southeast Asia and construction workers have stopped the routing of oil pipelines through ecologically sensitive areas…. Mundey is convinced that union environmentalism would have spread even further but for the destruction of the NSW BLF.

Fifty years on, the story of Jack Mundey and the NSW BLF still amazes people and will inspire all those who hope and fight for a better world. Blacklisted by employers and the Gallagher union alike, Mundey continued the ecosocialist fight for the rest of his life. He was elected to the Sydney City Council and after the sad disbandment of the CPA in 1991, he became an active member of the left-wing NSW branch of the Australian Greens. He gave his support along the way to numerous ecological and progressive campaigns, in which he was an inspiring and eloquent speaker. He proved, too, that the once despised “shit labourers”, many of them immigrants, were not brutes, but thinking, feeling human beings who could act with dignity to champion social and ecological causes, even to their own immediate cost.

The ruling class is liberal with its use of the word “great” to describe various bourgeois politicians and businesspeople, but to my mind Jack Mundey really does deserve the title of Great Australian. He, however, would be the first to insist that without the support of his members, he could have done nothing, and that he was a product of the great radical upsurge of the 1960s and ’70s. But he was also an active agent in that process. As the Russian Marxist G.V. Plekhanov earlier argued:

A great man is great not because his personal qualities give individual features to great historical events but because he possesses qualities which make him most capable of serving the great social needs of his time, needs which arose as a result of general and particular causes.29

The last, eloquent, word, however, should go to Jack himself:

Ecologists with a socialist perspective and socialists with an ecological perspective must form a coalition to tackle the wide-ranging problems relating to human survival…My dream, and that…of millions…of others might then come true: a socialist world with a human face, an ecological heart and an egalitarian body”.30

Notes

- ↩ Grammar pedants beware! Jack and his comrades always insisted that while “Labourers” had an apostrophe, “Builders” didn’t as the union belonged to the working-class, not the bosses!

- ↩ See Meredith and Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union. Environmental Activism and the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation, (Sydney: University of NSW Press, 1998), 9-10. The claim is made by the respected former Australian Greens Senator Bob Brown. One can argue this point. The term might have been used in the 1960s, however, there can be little doubt that Brown’s claims contain a lot of truth.

- ↩ Jack Mundey, Green Bans and Beyond, (Sydney: Angus and Robertson 1981), 66.

- ↩ Dogmen are known as banksmen in the UK and Ireland, but I have no idea if the practice of rising the load existed there or in North America.

- ↩ Kevin Cook and Heather Goodall, Making Change Happen: black & white activists talk about Aboriginal, Union and Liberation Politics (Canberra: ANU Press, 2013), 26. On page 28 of the same book, Valentin Sowada’s breathtaking photograph of Lance Shelton riding the hook high above Sydney’s streets is reproduced.

- ↩ On lower structures, riggers or dogmen could communicate with the crane driver with whistles, or in some cases, walkie-talkies.

- ↩ Pete Thomas, Taming the Concrete Jungle. The Builders Labourers’ Story (Sydney: Builders Labourers’ Federation, NSW Branch, 1973) 14.

- ↩ Ibid, 12.

- ↩ Paul True, Tales of the BLF: Rolling the Right, (Parramatta, NSW: Militant International Publications, 1995). Not paginated.

- ↩ Interview in Pat Fiske, 1985, “Rocking the Foundations: History of the New South Wales Builders Labourer’s Federation, 1940-1974”, Bower Bird Films, Sydney.

- ↩ Burgmann and Burgmann, 132. The ACTU is the equivalent of the AFL-CIO.

- ↩ A small pro-Moscow tendency broke away to form the Socialist Party of Australia at this time, and one of its central leaders was to play a less than admirable role against the BLF in years to come. When the CPA decided to close itself down in 1991, the SPA took the name: a source of ongoing confusion to newcomers to the Australian left!

- ↩ Mundey, 79.

- ↩ This was generally true across Australian society and industry. In 1970, immigrant worker resentment boiled over into a famous riot at the Ford Broadmeadows plant in Melbourne. Sick of listening to reports at union meetings in a language they barely understood, striking workers destroyed company property and chased a union organiser from the plant.

- ↩ Mundey, 56.

- ↩ Gregory William Mallory, “Two Case Studies of the Social Responsibility of Trade Unions in Australia”, PhD dissertation, Department of History, University of Queensland, 1999, 172. (Interview with Jack Mundey, Sydney, September 1990.)

- ↩ Burgmann and Burgmann, 54. “Sheilas” is a derogatory Australian term for women, and “poofters” is a homophobic slang term for homosexuals.

- ↩ A new edition of Carson’s seminal work was published in New York in 2002 by Houghton Mifflin.

- ↩ Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity (London: Verso, 1983). The book’s main title is a line from an extraordinarily poetic passage of The Communist Manifesto.

- ↩ John Tully, “Green Bans and the BLF: the labour movement and urban ecology”, International Viewpoint, No. 357, 17 March 2004.

- ↩ Mundey, 143.

- ↩ Ibid, 44.

- ↩ The Federated Engine Drivers’ and Firemens’ Association. The engine drivers in the union’s name operated stationary engines and moving construction machinery, but not railway engines.

- ↩ This vast sum translates to approximately A$24,000 million in 2020 dollars. Calculated using CPI Inflation Calculator.

- ↩ Tully, “Green Bans”.

- ↩ Thomas, 52. My estimate using the CPI Inflation Calculator.

- ↩ Thomas, 119. Also see Tully, “Green Bans”.

- ↩ Burgmann and Burgmann, 274.

- ↩ G.V. Plekhanov, On the Role of the Individual in History, Marxists Internet Archive.

- ↩ Mundey, 148.