An excerpt from Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties by Mike Davis and Jon Wiener.

During its January 1960 hearing, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights tepidly attempted to open a window on the police abuse of minorities in Los Angeles. Chief William H. Parker, notorious for his explosive behavior under questioning, immediately slammed it shut: “There is no segregation or integration problem in this community, in my opinion, and I have been here since 1922.” But long-suffering Los Angeles, he testified, was being inundated by barely civilized poor people from other regions. He suspected that Southern states in particular were sending their thriftless unemployed westward. “I attended a conference of mayors,” he submitted, “in which I had certain mayors tell me flatly that they would pay fares for certain people to move them into Los Angeles.” The result? “The Negro [in Los Angeles] committed eleven times as many crimes as other races.” As for Mexicans, “some of those people [are] not too far removed from the wild tribes of the district of the inner mountains of Mexico. I don’t think you can throw the genes out of the question when you discuss behavior patterns of people.” But Parker did not totally discount a civil rights problem in Los Angeles: “I think the greatest dislocated minority in America today are the police … blamed for all the ills of humanity.” “There is no one,” he complained,

concerned about the civil rights of the policeman.(1)

When Councilman Edward Roybal voiced the outrage of the East- side about the “wild tribes” remark, Parker denied that he had ever said it. His lie was exposed when a tape of the testimony was played to the city council, but the chief refused to apologize. Police critics, as he always reminded the public, were deliberately or ignorantly doing the laundry for gangsters and Communists.(2) In this controversy, as during every other during his seventeen-year tenure (1950–66), he could count on the city’s press (the Chandler family’s Times and Daily Mirror as well as the Hearst-owned Examiner [later Herald- Examiner]) to automatically editorialize in his support. Although his blood enemies ranged from J. Edgar Hoover to Governor Pat Brown, Parker was politically invulnerable thanks to lifetime tenure, a Hollywood publicity machine, and a blackmail bureau that rivaled Hoover’s.

Parker, who had earned a law degree while walking a beat, was adroit at conflating boss control of the police with civilian oversight. In 1934 he orchestrated, on behalf of the Fire and Police Protective League, a charter amendment that established a board of rights, composed of ranking LAPD officers, with exclusive jurisdiction over police misconduct. A subsequent amendment in 1937 gave chiefs life tenure and made it virtually impossible for the city to fire them. These were promoted as reforms that would once and for all remove political corruption from police administration. Joe Domanick, in his history of the LAPD, however, characterized the amendments as the equivalent of a coup d’etat:

A quasi-military organization had declared itself independent of the rest of city government and placed itself outside the control of the police commission, City Hall, or any other elected public officials, outside of the democratic system of checks and balances.(3)

As chief, Parker liked to flaunt his power in the face of an impotent and captive police commission. Before the Second World War the LAPD, especially its infamous Red Squad, had been the military arm of the open shop, of Harry Chandler and the anti-union Merchants and Manufacturers Association. Parker changed the balance of power. He continued to feed the conservative Republican appetite for polit- ical intelligence on their enemies, but he seldom broke strikes and absolutely never took orders. He had his own expansive dark agenda as well as an independent and largely impregnable political base. He replaced boss rule with cop rule and used the police commission to rubber-stamp his authority.

In June 1959, Herbert Greenwood, a Black attorney appointed to the commission by Mayor Norris Poulson, resigned in disgust, telling reporters that Parker “runs the whole show.” He cited the example of Ed Washington, a spectator at a fight the year before who “was told to move along by an officer and apparently didn’t move fast enough … the officer applied a judo hold and broke the man’s neck.” When Washington’s death was brought before the commission, Parker testified that the death was an accident and that there was “no need to make an investigation.” Except for Greenwood, the commission dutifully accepted the chief ’s word.(4) But even sycophants were some- times unsettled by the actual man behind the mask of Old Testament rectitude.

Parker was “Whisky Bill”: an “obnoxious, sloppy, sarcastic drunk,” who regularly relied on his driver, future LAPD chief Daryl Gates, to rescue him from disgraceful situations. According to Domanick,

He slurred his words, stumbled in and out of cars, and sometimes had to be literally carried home. Awkwardly prancing about shaking his arms doing a Sioux Indian dance he’d learned in his youth in South Dakota, or regularly throwing up after downing his pre-dinner bourbons in his house, among friends, was one thing. Showing up late, hung-over, and still drunk to review the Rose Parade with the mayor, and then giggling uncontrollably, quite another.(5)

But, like a movie star, he had a professional publicity bureau to safe-guard his public image.

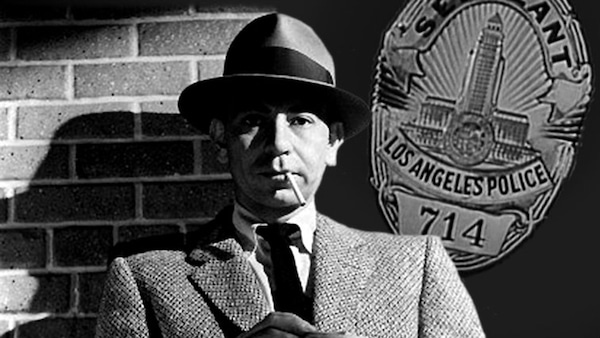

Dragnet had started as a radio show during the administration of Parker’s immediate predecessor, temporary chief William Worton (a Marine general with extensive experience in intelligence and espionage). Parker was initially wary of the show but also saw the opportunity to publicize his views on law and order. So when Jack Webb, the originator and star of the show, won network approval to produce both television and radio versions, Parker offered unlimited LAPD cooperation in production if Webb allowed the department’s Public Information Division (PID) to vet the scripts. Parker kept Webb on a short leash—forcing him, for instance, to never use the word “cop,” which the chief regarded as derogatory. In addition, adds Domanick, “the advisors closely examined the script to guarantee that the LAPD officers on Dragnet were ethical, efficient, terse and white.” It quickly became one of the top television programs of the 1950s and the template for a succession of television procedurals (twenty-five shows in all) and movies that exalted not only the LAPD macho ethos but also its icy and unnerving attitude toward the general citizenry.(6)

In addition to Hollywood, the PID—a unit of twenty permanent assigned officers—worked closely and often intimidatingly with the press: the Hearst-owned Examiner published an annual LAPD supplement lauding the chief and his men. Look magazine was persuaded to do a photo essay on the skirt-clad LAPD women, in which their marksmanship and homemaking abilities were equally stressed. There were even LAPD fashion shows. The PID also solicited articles on topics like the wonderful architecture of the LA Police Academy.(7) Parker, who insisted on an above-average IQ as an admission requirement for the academy, also made good use of literary talent on the force. Just as he himself had been the speechwriter for Chief James Davis in the 1930s, he now made a young second-generation cop, Gene Roddenberry, his chief speechwriter and script consultant. In 1957 Roddenberry resigned to write full time for television, and legend claims that Chief Parker was the model for Star Trek’s Mr. Spock— half alien, half human, with no sense of humor.(8)

An FBI agent assigned to monitor and report on Parker’s activities once described him as “a psychopath in his desire for publicity.” Undoubtedly. But the chief was also shrewdly selling the need for the LAPD. In several speeches published in academic journals during the mid 1950s, Parker expounded a surprisingly pessimistic doctrine of law enforcement, emphasizing that crime moved in cycles determined by socioeconomic factors beyond the power of the police to control: “Lacking the ability to remedy human imperfection, we must learn to live with it. The only way to safely live with it is to control it. Control, not correction, is the key.” He added that “police field deployment is not social agency activity …[it] is concerned with effect, not cause.” The public, however, chronically underestimated the prevalence of crime and placed naïve belief in sociological solutions such as the probation and youth services agencies that Parker scorned. The result was an unwillingness to properly finance and support tough policing. Parker’s remedy was that police reformers must intervene in the “creation of a market for professional law enforcement.”(9)

Generating this demand meant using the media to show that crime lurked in every crevice of urban society and was only held at bay by a “thin blue line” of hard-as-nails cops. Police critics, if they so dared, would have to pass through a gauntlet of irrefutable crime statistics scientifically amassed by police analysts. (Parker’s belief in letting no crime, however trivial, go unpunished anticipated the contemporary “broken windows” school of policing.) What went unsaid, of course, was that the easiest way to generate politically dramatic indices of criminality was through the use of dragnets, racial profiling, random traffic stops, raids on gay bars, warrantless home break-ins, and the promotion of ordinary misdemeanors to felonies whenever possible. The relentless, virtually industrialized policing of the southern and eastern districts of the city, as well as gay Hollywood, automatically became its own self justification. Mob invaders from the East and Red conspirators were just the frosting on Parker’s cake. White-collar crime, meanwhile, was scarcely acknowledged.

Notes:

- United States Commission on Civil Rights, Hearings Before the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Hearings Held in Los Angeles, January 25, 1960 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960), 325, 327, 330–1.

- LAT, January 29 and February 3, 1960.

- Joe Domanick, To Protect and Serve: The LAPD’s Century of War in the City of Dreams (New York: Pocket Books, 1994), 95.

- LAT, June 20, 1959.

- Domanick, To Protect and Serve, 146. See also John Buntin, L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America’s Most Seductive City (New York: Broadway Books, 2010), 170. It is claimed that Parker later went on the wagon: Alisa Kramer, “William H. Parker and the Thin Blue Line: Politics, Public Relations and Policing in Postwar Los Angeles,” PhD diss., American University, 2007, 84. This is the only actual biography of Parker and thus very useful, but Kramer does depend heavily on Domanick.

- Domanick, To Protect and Serve, 133.

- Kramer, “William H. Parker,” 73–4.

- Ibid., 78.

- Ibid., 184.