Eleven statues of Confederate officers, including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis, stand in the National Statuary Hall Collection in the U.S. Capitol. In response to House Democrats’ recent effort to fast-track their removal, Senator Mitch McConnell and other rearguard cultural defenders have said that to do so would erase history.

Many Americans are startled to learn that Confederate statues are in the Capitol at all. On Twitter, this surprise has often taken the form of a question:

Why in the hell are there Confederate statues in the Capital? Wait—there’s a statue of Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens and nine other confederates in the U.S. Capitol building? Good Lord, what are they doing there?

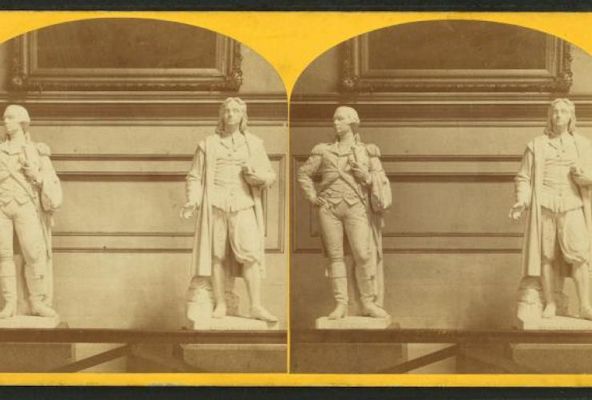

Good questions. Amid the widespread defacings, topplings, and official removals of statuary representing not only enslavers but also racist leaders of many kinds, the presence there of Confederate monuments—not in former slave states but in the seat of the government that the Confederacy fought—seems bizarre indeed. People who remember, as I do, seeing the statues on childhood visits to the Capitol will be less surprised, but I suspect that even we have thought little about the National Statuary Hall Collection’s contents, or even its existence. A large, oddball batch of mostly old memorials, the collection is centered in the National Statuary Hall, beside the Rotunda, and scattered about in other rooms; many of its subjects are at best obscure. At first glance, the collection might seem, aside from the outrageous presence of the Confederacy, innocuous enough, if a bit antique.

But the stark reality is that the U.S. government’s peculiar relationship to the Civil War made those Confederate statues a defining feature of the whole National Statuary Hall Collection—a fulfillment, even, of what became its purpose. What Confederate figures are doing in the collection is worth knowing, because it bears on larger, even more unsettling political and cultural processes that have marked U.S. public discourse regarding race and racism in the past three centuries.

The National Statuary Hall Collection was born not with the Capitol but in the midst of the Civil War. In 1864, as the conflict entered its final year, Representative Justin S. Morrill of Vermont, a founder of the Republican Party, sponsored a bill authorizing the president to invite each state to commission and send the federal government statues of up to two heroes born in the state. The House had moved out of its first chamber, known for terrible, echoing acoustics, and into the current one. The former chamber, abandoned and in disrepair, was to be fixed up for displaying the statues. President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law on July 2.

Given the intensity of war, the statuary project couldn’t have looked very urgent. That same month, the Senate also approved the radical Republicans’ Wade-Davis Reconstruction Bill, with exacting conditions for readmitting the Confederate states to the Union. The war had suspenseful moments ahead, but Congress and the president were already considering how to deal with a defeated white South. Lincoln would soon veto the Wade-Davis bill. To him, it was retributive, not restorative. In the 1864 election, a group of radical Republicans split from Lincoln and ran the Civil War hero John Fremont against him; Morrill, author of the statuary bill, ran on the Lincoln side. A deep division was opening in the national government over proper relations between a victorious United States and the former slave states. What went on in the National Statuary Hall dramatized the resolution of that conflict.

No statue was installed in the hall until 1870. The war was over, Lincoln was dead, Ulysses S. Grant was president, and radical Reconstruction, if not yet a dead letter, was starting to topple when the collection received its first entry: Nathanael Greene of Rhode Island.

Greene was an easy choice. A Continental Army general born in Rhode Island, he oversaw famous battles in the southern theater that brought about U.S. victory in the War of Independence. He was remembered then, and is remembered now, as a great founding-era New Englander, product of the region that, upon winning independence from Britain, began a process of abolishing slavery and becoming the free-state North, in opposition to the slave power of the South.

But Greene had a brief post-Revolution career, little discussed and provocative to consider in light of his inaugural role in the National Statuary Hall Collection. In 1782 the grateful states of Georgia and South Carolina awarded the general some large rice plantations. Even as Rhode Island was beginning its gradual abolition of slavery, the war hero moved down to Georgia, bought black children, women, and men, and went into the brutal forced-labor operation that produced rice at huge scale.

He wasn’t successful in the undertaking, and he died in 1786. Still, in contrast with famous men born to the slaveocracy, such as his former commander George Washington, Greene represents an innovation with regard to the institution of slavery. A northerner branching out into rice production, he was pursuing the novel interstate opportunities for gaining wealth that had suddenly been made available by the victory he’d helped deliver. Nor was Greene alone. General Anthony Wayne, Greene’s friend and former junior officer, was also given Georgia plantations, and he too made a major attempt, also unsuccessful, to get rich as a slaver and rice planter as a reward for his service. In Wayne’s native Pennsylvania, commercial agriculture had never depended on slavery in the way southern agriculture did, and like Rhode Island, Pennsylvania was in the process of abolishing it.

We often view the period between the War of Independence and the Civil War in terms of rising sectional conflict, especially over slavery. But Wayne’s and Greene’s commercial efforts point to ways in which the commercial ambitions that were unleashed by independence didn’t just divide the sections but also tied them together, also over slavery.

It was on General Greene’s Georgia plantation, for example, that another New Englander, Eli Whitney, invented the cotton gin. That triumph of Yankee ingenuity quickly pushed cotton production to the King Cotton level, resulting in a grotesque proliferation of human suffering, as well as in the southern planter class’s growing eagerness not only to protect the institution that caused the suffering, but also to expand its geographic scope, the expansion that led to the crisis of war. Greene’s prominence as a nationalizing figure may be seen today not only in the National Statuary Hall Collection but also in the dozens of regionally diverse places named for him, including Greene County, Georgia; Greenville, Ohio; and the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York. His rice planting in Georgia symbolically unifies the whole of the founding elite, North and South, unifies U.S. independence itself, in the racial slavery that led directly to the Civil War.

The Greene statue, launching the National Statuary Hall Collection in 1870, has a related symbolic importance for a new unification that went on after the Civil War. Reconstruction ended formally in 1876, but it wasn’t until 1909 that Virginia sent the statue of Lee, the first commissioned by a former slave state, to the Capitol. Now Greene’s was not the only statue in the hall to blend the legacy of slavery with the glow of U.S. heroism.

Greene’s symbolic role in unifying the white northern elite and the white southern elite was by no means overtly expressed by his statue. Rhode Island hadn’t sent it for the purpose of expressing a bridge between the sections, via slavery; few visitors would have known of Greene’s use of slave labor in Georgia.

Virginia, however, sent Lee’s statue precisely for the purpose of announcing, in the Capitol, the unification of the former slave economy’s emotional heartland with the heart of national government. It was for that purpose, too, that Lee was accepted in the collection by the Joint Committee of Congress on the Library of Congress, which oversees it. The federal government was signaling, via the National Statuary Hall Collection, the sectional reconciliation going on politically in the Capitol and the White House.

Even as the United States declined to enforce the Constitution in the former Confederate states, demolishing black citizens’ lives and liberty, first Lee and then the ten other Confederate statues arrived in the hall, with others that have since been replaced, and were embraced by the collection. The whole federal government approved. Only one person in Congress, Senator Weldon D. Heyburn, Republican of Iowa, spoke against the Lee statue, in terms that some people are using now: these were traitors to the United States. His colleagues considered Heyburn’s fulminations about the former Confederacy embarrassingly old-fashioned, the senator a “dodo.”

Building out the National Statuary Hall Collection mapped directly to the development of racial segregation in the South and to the growth of Lost Cause nostalgia in both the white South and the white North. The collection’s effective purpose had become to memorialize figures of the Confederacy and “the Union,” as the United States was called in this context, on equal terms.

It is not just the statues themselves but the underlying compositional structure of the whole collection that teaches visitors subliminal civics lessons. Like the United States Senate, the collection is subject to an “equal suffrage” provision, by which, per Morill’s bill, each state has the right to be represented by two statues. The collection is thus a product almost solely of the states’ legislatures. Its composition supports a view of federalism, always partial, legally outmoded by the Civil War, in which nationhood serves mainly as an organizer for the states as sovereign lawmaking entities, not as a force of its own.

Under those conditions, the hall got crowded. Healing an old conflict through sheer togetherness, a gathered host of greats has been telling, for a long time, a seemingly unbroken story reaching back to the colonial period and forward to the present: Ethan Allen and Stephen Austin, Samuel Adams and Alexander Stephens, John Calhoun and Gerald Ford, John Winthrop and Dwight Eisenhower, John Fremont and Jefferson Davis, a brotherhood of white, Protestant men drawn from various regions, periods, and political persuasions and honored as both state and national heroes.

Surprise at finding Confederates in the collection is thus relatively new. Generations of schoolchildren trooping through the hall were expected to take it as given that those men played an important part in a glorious, if sometimes poignant American tale. I was one of those children, and I can tell you that the “boy’s own adventure” imaginations of white kids like me, growing up in the Northeast in the 1950s and ’60s, were crammed with Marvel and DC superheroes, the Knights of the Round Table, Lee and Grant and other Civil War officers, Robin Hood and his Merry Men, Jesse James, Tarzan, and a host of other romantically projected Anglo-American figures of high action, whose origins mingled fiction, myth, and history. There was nothing strange to me about finding Confederate leaders in the Capitol. Not finding them there would have been strange. Creating that impression was an important part of what the National Statuary Hall Collection was for.

It is true that the collection’s cast of characters has undergone development, though not much, and very slowly. Many of the Confederates have been shuffled into dim corners of other rooms, but only a few have been recalled by their states and replaced. As early as 1905, Illinois sent a statue of Frances E. Willard, a suffragist and temperance reformer, the first of only eight women of the hundred people now represented. In 2009 Alabama replaced a Confederate officer and member of the Confederate Congress with Helen Keller. Last year, Nebraska replaced William Jennings Bryan with Chief Standing Bear; six other indigenous people are represented, including Kamehameha I and Sacagawea. It is worth considering indigenous people’s prominence, very relatively speaking, in such an overwhelmingly white group. The imaginative pantheons of my childhood also included Cochise, Crazy Horse, Geronimo, and Sitting Bull. Conquered and depopulated, culturally erased, and now making up less than 1 percent of the national population, indigenous North Americans are so overwhelmingly invoked, in such stereotyped imagery, across our whole popular and official culture, that the fact can barely register. A fantastical white identification with the American Indian that began at least as early as the nation’s founding is reflected in the National Statuary Hall Collection.

As for the collection’s representation of other groups, there are thirteen Roman Catholics, two Hispanic people, two Mormons, one Jew, nobody openly gay, nobody Asian American, and nobody Muslim. No state has ever placed a statue of an African American in the National Statuary Hall Collection: the hall’s statue of Rosa Parks, commissioned by Congress, and the statue of Frederick Douglass in the Capitol Visitor Center, commissioned by the District of Columbia, are not officially included. While Florida has said that it will replace a Confederate general with a statue of the educator and civil rights activist Mary Mcleod Bethune, that hasn’t happened yet. The collection’s foundation in the separate states’ governments makes such decisions, as well as their execution, so dependent on contingent factors that the antique hodgepodgery of the collection remains a built-in feature.

The National Statuary Collection should not be mistaken for an august grouping that, excepting pollution by the Confederacy, makes a strong national expression of U.S. heroism. We should consider what purpose the collection might serve now, in the context of the purposes it has served ever since Greene, Rhode Island general and Georgia slaver, stood there, alone, in the echoing, recently renovated former House chamber. The long-overdue removal of Confederate figures may have the unfortunate effect of further obscuring the political and cultural processes that enshrined them, both in the National Statuary Hall Collection and in popular imagination . Avoiding a confrontation with the collection’s purpose in honoring the men who took up arms against the United States denies stubborn, deep-seated urges in the long construction of national memory.