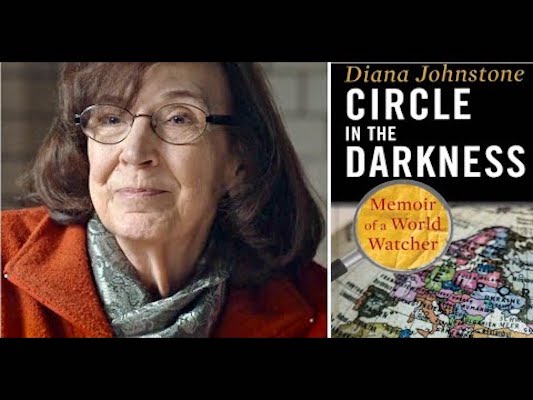

Diana Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness: Memoir of a World Watcher (Atlanta: Clarity Press, Inc., 2020), 435 pages, $24.95, paperback.

The back cover of Diana Johnstone’s Circle in the Darkness calls the memoir “a veteran journalist’s lucid, uncompromising tour through half a century of contemporary history,” one that “recounts in detail how the Western Left betrayed its historical principles of social justice and peace and let itself be lured into approval of aggressive U.S.-NATO wars on the fallacious grounds of ‘human rights.’” Indeed, it is. Diana Johnstone’s fiercely courageous and independent reporting, historical analysis, and activism have stayed the course while managing to chalk up a veritable army of opponents: establishment Democrats, infantile 1960s New Leftists, would-be French student revolutionaries, identity politics adherents, influential U.S. and French intellectuals, Serbian-hating neoliberals promoting Responsibility to Protect (R2P) wars, NATO, and the U.S. National Security State. The people and institutions that have been exposed by Johnstone’s accurate reporting reveal just how well she’s been doing.

Against this lineup of detractors, she has remained a courageous and principled individual who has identified and condemned the criminals who have laid waste to nations and people across the world, including U.S./NATO war makers, corporate capitalists, and the R2P neoliberal “humanitarians.” For more than fifty years she has reported on peace and militarism, economic equality, and democratic politics, as a person of the left in the best sense of that term—presenting accurate insights and engaging in nonviolent efforts to abolish war and build a democratic socialist alternative to capitalism and imperialism.

The book chapters are organized around personal and political themes, issues, and events. These include her early childhood in Minnesota and political awakening with the Farmer-Labor Party; the New Deal; the Second World War; politics and militarism; learning about the world through university studies and travels to Europe, where she spent decades living in France; residing and working in Washington during the “McCarthy Circus”; becoming involved in the movement against the Vietnam War, including the May 1970 faculty-student antiwar efforts at the University of Minnesota after the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and the killing of students at Kent State; work on behalf of people’s diplomacy to end that war; Italy’s “Hot Cold War” after the Second World War; the U.S. National Security State and imperialist actions against Afghanistan and Iran; the “Israeli Connection” and oppression of Palestinians; U.S. media terrorism allegations against the Soviet Union and the alleged “Bulgarian” assassination plot against Pope John Paul II; French and German state politics including insights on May 1968 in France; the Joint Criminal Enterprise known as the U.S./NATO war against Yugoslavia and the bankruptcy of “humanitarian imperialism”; and concluding chapters on “Hubris and Humanity” and “Truth” that shared insights from university studies, teaching, politics, and writing. The chapters, therefore, range from the familial and personal to the worldly and political. They reflect her efforts to express and influence the struggle for justice and peace, laying out truth claims that challenged the U.S. and Western capitalist class and national security elite. This often-difficult labor provided the evidence and rational arguments that might guide us to the most accurate understanding of key historical events.

Rather than cover many issues and events with a quick brush that cannot do justice to her work, I will focus on two key historical events that define who she is and what she has done: the Vietnam War, the May 1970 student protests, and her antiwar efforts at the University of Minnesota where she was teaching at the time; and the U.S./NATO war against former Yugoslavia. I have chosen these two among the many subjects in the book because they reflect her consistent and relentless journey in addressing and challenging U.S. and Western imperial violence against poorer nations.

Let us begin with Johnstone’s thoughts on the Vietnam War, which, in the words of the widely watched Ken Burns’ PBS series, was “begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence, and cold war miscalculation.” Johnstone emphatically rejected this bogus claim, as her involvement in the U.S. antiwar movement showed clearly that it “was wrong on every count, and pretexts given were false. I did not come from the Left, and it was not the Left that turned me against the war, but my opposition to the Vietnam War brought me in contact with the Left, so much so that I have been identified forever after as ‘on the left.’”[1] She concluded that the war was “a violent attempt at nation-breaking, against a people with a strong sense of national identity who turned to communism precisely because it seemed to be the key to unity.”[2]

Johnstone’s years in the antiwar movement included time in France during the conflict, where she befriended “scholars, both American and French, as well as Vietnamese, experts in Asian history, whose contribution to the antiwar movement was essential. Scholarship and honest journalism were necessary to combat the propaganda and the delusions spread by the United States in its foolish attempt to reverse history in Asia.”[3] This is a critical point that weaves itself throughout her book: Asian and Vietnamese history and U.S. imperialist history were a necessary first step for U.S. citizens’ opposition to that horrific war.

Her approach to the antiwar movement, therefore, was to inform people with verified knowledge about the violence in Vietnam “in the expectation that popular opposition would force leaders to put an end to this flagrant injustice. This was grounded in a deep unquestioned faith in the democratic process.”[4] To inform others about the flagrant illegal and unconstitutional invasion of Vietnam—and Cambodia and Laos—meant that one had to know something about Vietnamese history, its colonial struggle against France, and its resistance against the United States in order to counter the official story and convince others of the truthfulness and justice of one’s position on the conflict. Johnstone did that as a young instructor at the University of Minnesota and has continued this fact-based truth journey ever since.

At the time of the Cambodian invasion and Kent State killings, Johnstone became involved in a Community Contact program at the University of Minnesota in which hundreds of students left the campus each evening to ring doorbells and talk with Minneapolis residents. They would introduce themselves and state that they wanted to talk with residents “about why we’re striking and about the war in Southeast Asia.”[5] An article on this exceptional effort was written by the late journalist Molly Ivins, then a young reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune. This campus-to-community effort to carefully and patiently explain the reasons for student antiwar protests was rarely done, even at the height of May 1970 campus protests against the conflict. Most activism was contained within campuses, leading to student strikes and a small number of graduation cancellations. The exemplary efforts against the Vietnam conflict by the faculty-student group are similar to the fine and consistent antiwar efforts of the U.S. Women’s Strike for Peace (WSP)—as discussed by Mike Davis and Jon Weiner in Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties. The group was “an anti-hierarchical organization with impressive local autonomy. Their meeting with Vietnamese women in 1965 had made WSP, in L.A., and nationally, some of the most effective leaders of the antiwar movement.”[6]

For Johnstone “and certainly for a number of others,” the Community Contact program “represented ‘higher learning’ in the best sense of the term. While on strike we were studying, learning and teaching even more intensely than usual, using scholarly sources and methods, and immediately applying our learning to a socially useful cause. By ‘teaching’ the community, we were teaching ourselves about that community, about its attitudes, its weaknesses and its potential.” She had been involved in the May 1968 protests in Paris and stated that she “could not help feeling that, all things considered, especially the difference in the size of the population, the Minnesota May could be compared very favorably with the other one. It was proportionately just as big, but incomparably more focused and more peaceful. Perhaps for those reasons, it went virtually unnoticed in the rest of the world, or even in the rest of the country.”[7] Had the Minnesota community effort been replicated on every U.S. campus that May 1970, the student antiwar movement would have become immeasurably stronger. Participants would have moved on to a far deeper understanding of that war and other political questions.

Johnstone is self-reflective about the political struggles in which she engaged and drew lessons from her university studies and teaching. “Without realizing it at the time, I represented an ‘old guard’ devoted to the rational search for factual truth and reasoned solutions to problems.” She rejected the fashionable postmodernist view that “there are multiple truths, each one as true or not true as the others,” especially when it came to such issues as Vietnam. The “contesting” narrative view, therefore, would essentially equate the views of President Johnson’s advisers Walt Rostow and McGeorge Bundy with that of Noam Chomsky.[8] Teaching and struggling to find the truth for Johnstone is “the vocation of stimulating ‘elite’ understanding in each and every person.”[9] At a time when allegedly equal truth claims about epic historic events were legitimized—ultimately leading influential intellectuals and pundits to parade apologies for imperialist and militarist policies—Johnstone’s claim that there are objective truths to be found outside of official state propaganda was a revolutionary act.

Her analysis of the U.S./NATO war against former Yugoslavia in this memoir and Fool’s Crusade that exposes the bankrupt R2P “humanitarian” interventions complements other fine critiques of that conflict and U.S. imperialism that lay bare the dominant U.S./NATO view of the Yugoslavian assault and R2P propaganda.[10] Johnstone and these authors are squarely within the view of R2P put forth by most UN member nations. At the 2000 South Summit meeting of developing nations, 133 countries declared: “We reject the so-called ‘right’ of humanitarian intervention, which has no legal basis in the United Nations Charter or in the general principles of international law.”[11]

Johnstone’s basic argument on Yugoslavia is simple and true: for the first time, NATO “abandoned its defensive posture and attacked a country that posed no threat to its member states, outside the NATO treaty area, and without seeking UN Security Council authorization. International law was circumvented in the name of a higher moral purpose.”[12] The war was not a right-wing, conservative, or Republican venture, but “was waged by the political center-left. The NATO governments were mostly led by liberals and ‘Third Way’ social democrats.” The attack on Serbia was endorsed “by politicians and intellectuals identified with the left, who exhorted the public to believe that the United States and its allies no longer made war to satisfy selfish interests, but might be coaxed into using their overwhelming military might to protect innocent victims from evil dictators.” This rush to war, she concludes, “was orchestrated by both major parties” and created “considerable confusion in the very segments of public opinion that would normally be expected to oppose war. In most Western countries, only a few drastically weakened fragments of left-wing movements and isolated individuals still remembered that humanitarian intervention, far from being the harbinger of a brave new century, was the standard pretext for all Western imperialist conquests of the past.”[13]

The war was “presented to the public as a happy ending to the serial drama of Yugoslavia as recounted by the media throughout the previous decades.” Ultimately, what unfolded was “a collective fiction told and retold, written and rewritten, by very many people…paid propagandists and public relations officers, pontificating commentators, prejudiced editorialists, ambitious politicians, outright liars—as well as talented opportunists and conformists.” This collective fiction was repeated so often that it “has become a formidable myth perpetuated by the powerful institutions and individuals whose own credibility is at stake in its maintenance.”[14] The attack on Yugoslavia was one horrific part of U.S.-led globalization that empowered “the transnational private sphere, dominated by ever more powerful corporations, financial institutions, and wealthy individuals.”[15] It violated the U.S. Constitution and the UN Charter, which “was replaced by the moral authority of a vague entity called the ‘International Community,’” that is, “the new [U.S.-led]” imperialism.[16] When all was said and done, it was the United States alone that decided “who enjoys protection of the law and who does not. Punishment may be visited on any state accused of violating human rights, supporting terrorism, or building weapons of mass destruction, over which the United States intends to preserve its virtual monopoly.”[17]

With her eyes on the prize, Diana Johnstone has stayed the course to oppose U.S. and Western aggression, using her critical skills to expose endless horror and insisting that a truthful understanding of historical events remains a necessary tool against murder and illegality. We are deeply indebted to her.

Notes:

[1] Diana Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness: Memoir of a World Watched (Atlanta: Clarity, 2020), 51.

[2] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 53.

[3] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 61.

[4] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 61–62.

[5] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 79.

[6] Mike Davis and Jon Weiner, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (London: Verso, 2020), 138.

[7] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 81.

[8] Chomsky’s magisterial trilogy on Vietnam and U.S. foreign policy: American Power and the New Mandarins (New York: New Press, 1967); For Reasons of State (New York: New Press, 1970); Toward a New Cold War: U.S. Foreign Policy from Vietnam to Reagan (New York: New Press, 1982).

[9] Johnstone, Circle in the Darkness, 102.

[10] Jean Bricmont, Humanitarian Imperialism: Using Human Rights to Sell War (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2006); Noam Chomsky, The New Military Humanism: Lessons from Kosovo (Monroe, ME: Common Courage, 2000); Maximilian Forte, Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya and Africa (Montreal: Baraka, 2012); David Gibb, First Do No Harm: Humanitarian Intervention and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2009); Michael Mandel, How America Gets Away with Murder: Illegal Wars, Collateral Damage and Crimes Against Humanity (London: Pluto, 2004); Michael Parenti, To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia (London: Verso, 2000).

[11] Quoted in Mandel, How America Gets Away with Murder, 112.

[12] Diana Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade: Yugoslavia, NATO and Western Delusions (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2002), 1.

[13] Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade, 2.

[14] Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade, 5.

[15] Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade, 6.

[16] Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade, 259–60.

[17] Johnstone, A Fool’s Crusade, 265.