This collection of essays is organized by Professor Lau Kin Chi on behalf of the Executive Team of the Global University for Sustainability, in remembrance of Professor Immanuel Wallerstein on the anniversary of his death on August 31, 2019. (Click here to see all essays in this collection.) We would like to thank Professor Katharine Wallerstein for sharing some photos included below. —Eds.

Contributor Index

- Lau Kin Chi (Lingnan University, Hong Kong, China)

- Huang Ping (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China)

- Wen Tiejun (Renmin University of China, Beijing, China)

- Sit Tsui (Southwest University, Chongqing, China)

- Remy Herrera (University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France)

- Gustave Massiah (Centre de recherche et d’information sur le développement)

- Patrick Bond (University of Western Cape, South Africa)

- Boris Kagarlitsky (Institute of Globalization and Social Movements, Russia)

- Boaventura de Sousa Santos (University of Coimbra, Portugal)

- Ari Sitas (Chair of the National Institute for Humanities and the Social Sciences, South Africa)

- Noah Tsika (City University of New York, USA)

History may reserve its surprises

Lau Kin Chi [top]

I remember Immanuel Wallerstein with fondness. I feel that one way to celebrate his rich life is to organize a collection of essays of friends writing on their personal interactions with Immanuel. The collection would be published in English, Chinese and Turkish.

The first time I met Immanuel was at a tent in Nairobi in January 2007, during the World Social Forum. I had met Samir Amin in 2002 and Francois Houtart in 2003, and we had developed an instant fondness and respect for each other, and had since worked closely together in world social forums and other global projects such as publishing Globalizing Resistance in French, English and Chinese. When the World Forum for Alternatives organized a panel in Nairobi to discuss financial and ecological issues, Samir, Francois, Immanuel, Ebrima Sall, Marcos Arruda, Dai Jinhua and I were there. Immanuel was gentle but firm in his ideas. He was then aged 77. When we chatted, he liked the black T-shirt I was wearing, which we ourselves made, with the words “We can make a difference” on the front and “Another world is possible” on the back. He would like me to send one such T-shirt to him for his wife, and said Beatrice and I were about the same height.

After the forum, in his fortnightly Commentary on 1 Feb 2007, Immanuel spoke highly of this World Social Forum (WSF):

In this chaotic situation, the WSF is presenting a real alternative, and gradually creating a web of networks whose political clout will emerge in the next five to ten years. Participants at the WSF have debated for a long time whether it should continue to be an open forum or should engage in structured, planned political action. Quietly, almost surreptitiously, it became clear at Nairobi that the issue was moot. The participants would do both – leave the WSF as an open space that was inclusive of all those who wanted to transform the existing world-system and, at the same time, permit and encourage those who wanted to organize specific political actions to do so, and to organize to do so at WSF meetings.

The key idea is the creation of networks, which the WSF is singularly equipped to construct at a global level… The WSF is also spawning manifestos… Finally, there was the attention turned to what it means to say “another world.”… The discussions, the manifestos, and the networks constitute the offensive posture… It is not that the WSF is without its internal problems. The tension between some of the larger NGOs (whose headquarters and strength is in the North, and which support the WSF but also show up at Davos) and the more militant social movements (particularly strong in the South but not only) remains real. They come together in the open space, but the more militant organizations control the networks. The WSF sometimes seems like a lumbering tortoise. But in Aesop’s fable, the glittering speedy Davos hare lost the race.

Unfortunately the tensions and debates of 13 years ago that Immanuel outlined continue to exist today in the WSF, and the rabbit is still sleeping in the path ahead. Fortunately, the lumbering tortoise has persisted in moving on despite all the adversities. Immanuel always had this optimism about possibilities, which I think is necessary for bold experiments to be taken up and hope to be sustained.

The last time I met with Immanuel was at the Montreal World Social Forum in August 2016. The Global University for Sustainability was officially inaugurated one year ago at the Tunis World Social Forum, after a preparation of 5 years, and the 200 Founding Members are thinkers and activists from across different disciplines, sectors, generations and locations. Immanuel, Samir and Francois, along with others, were Founding Members. At the Opening March in Montreal on August 9, along with Patrick Bond, Claudia Caballero and the Chinese members Dai Jinhua, Sit Tsui, Alice Chan, Auyeung Lai Seung and myself, Immanuel and his wife Beatrice walked with the Global University banner. He was 86, but walked briskly. They had the company of their 12-year old granddaughter Layla at the World Social Forum, about which Immanuel was particularly pleased, as he in his childhood and teen years had often taken to the street to protest Nazism. We walked for over an hour, taking care not to tread on the little dog that the family had brought along.

We made an appointment with Immanuel to interview him at the lobby of his hotel four days later. Immanuel came on time, but I saw that he was somewhat limping. I was concerned he had tired himself out during the march. Then I was relieved and had to hide my grin. In rushing to our appointment, Immanuel had his right shoe on his left foot, and left shoe on his right foot. We quickly invited him to sit down. Dai Jinhua and I are professors in Cultural Studies, so we had agreed that we would focus on Immanuel’s life story, especially his formative years. We could leave theoretical discussions to the seminars. I requested Immanuel to talk about some of the turning points in his life, speaking to young people as our anticipated audience.

Immanuel told us how his parents from Central Europe were migrants to New York on economic reasons, and in the late 1930s had wanted to help people from Europe escape the Nazis. Born in 1930, Immanuel was very young and did not always understand the full meanings of the discussions at home among his parents and their friends, but he had thus been politically oriented to the left. He had later developed an interest in Gandhi and India, but because of links to African friends, and because of his bilingual capacities in English and French, he did his dissertation on the role of voluntary organizations in the politics of British and French West Africa. Later, he visited most of the African countries.

Immanuel mentioned one point which I feel is important: many people going to Africa would still impose their western points of view. Indeed, white supremacy at the heart of eurocentrism often goes unchallenged or, worse still, unnoticed. It is not only white people from the global north that harbor Eurocentric values, non-white colonized peoples from all classes in the global south may not be immune. The modern education system across the globe holds the core values and perspectives of eurocentrism. Samir coined the word “eurocentrism” back in 1988, and wrote a book on it. A nationalist cloak veils the essence of eurocentrism in many countries of the global south, and the supremacy of so-called western science and technology, institutions, culture and taste is accepted by not only the elites, the middle class, but also sometimes the under-classes. Yet, for Immanuel, he said his African friends educated him to see the world as Africans saw it, and surely, Frantz Fanon had an influence on him.

Not everyone would appreciate such education from African friends, so how was Immanuel exceptionally self-reflective? I think this has to do with his being situated in New York, the belly of the beast, and witnessing as a kid the horrors of Nazism which was inherent in the European civilization, going through McCarthyism as a young man, and baptized by the global youth revolts of 1968. Immanuel said 1968 undid some of the simplistic liberal ideas that he had before. It was a major turning point in his life when he took an understanding of the limitations of the possibility of transformation—a bit-by-bit transformation of the world just wouldn’t work, and we needed another world which is possible and which is necessary. He saw that the activities of anti-systemic movements were structured by systemic constraints from which they were never able fully to release themselves, hence he argued for a “world-system” to be the only plausible unit of analysis, and all analysis had to be simultaneously historic and systemic. On the other hand, he stressed that all systems have deep cleavages, and they never succeed in eliminating their internal conflicts. He named the five major cleavages—race, nation, class, ethnicity and gender, but he thought class struggle was the paramount one.

Immanuel wrote in the last Commentary, the 500th issue on July 1, 2019, entitled “This is the end, this is the beginning”:

So, the world might go down further by-paths. Or it may not. I have indicated in the past that I thought the crucial struggle was a class struggle, using class in a very broadly defined sense. What those who will be alive in the future can do is to struggle with themselves so this change may be a real one. I still think that and therefore I think there is a 50-50 chance that we’ll make it to transformatory change, but only 50-50.

In the midst of the intertwined capitalist crises of today—global warming, pandemic, polarization, economic crash, food shortage, strangling poverty, and rumbling war machines—perhaps we need to ask again, not only the question socialism or barbarism, but communism or extinction? 50-50?

The conversations among Andre Gunder Frank, Giovanni Arrighi, Samir Amin and Immanuel Wallerstein, presented in the two volumes Dynamics of Global Crisis (1982), and Transforming the Revolution (1990), demonstrate the creative tensions in vision, analysis and proposition about confronting the capitalist crisis we face today. They ended the second volume with the beautiful words, “History once again may reserve its surprises… A luta continua”. Whether it is a chance of 50-50, or 99.9-0.1, against all odds, there is no alternative other than to hold on to the baton handed over to us by the veterans for revolutionary change, and struggle. We must have faith that History may reserve its surprises.

Meeting in Rio de Janeiro in 2003 (from left to right): Samir Amin (1931-2018), Immanuel Wallerstein (1930-2019), Giovanni Arrighi (1937-2009) and Andre Gunder Frank (1929-2005). Photo taken by Beverly Silver.

Huang Ping (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China).

Huang Ping (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China) [top]

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

I have started reading Immanuel Wallerstein’s writings in the 1980’s. To begin with it was the introductory papers written by Professor Luo Rongqu of Peking University, and then it was the first volume of the Modern World System translated by Professor Luo et al. As for getting to know him in person it had to be almost ten years later in the 1990s. First it was to listen to his keynote speech at the World Congress of International Association of Sociology(IAS), and then bringing one of his books to him for autographing. That book seems to have been hidden in my bookshelves now. In the years following, I managed to see him and talk to him almost every year. It was either in the U.S. or more often it was in Paris. That was because he would spend almost half the time every year to do research work at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS). He had a tiny office there, even smaller than the cubicles of the veteran masters in Chinese Academy of Social Science during the 1980s-90s. Yet two people could fit in there sitting closely together. I often took the opportunity of attending UNESCO meetings to go to him in the afternoon, and spend the whole afternoon there talking with him. The last time of meeting him was after the 2007-2008 financial tsunami. We were in Armenia attending the World Congress of International Institute of Sociology (IIS). At the time I was still Vice President of the International Institute of Sociology. The president Bjorn Wittrock and I jointly invited Wallerstein to speak on the international financial crisis. He began with a sentence that I have analyzed this crisis in papers and books before and would not talk about it now—had attracted enthusiastic applauses from the audience, which showed the high willingness of the audience for his newer insights on the cirsis. What he talked about that day was in fact issues regarding the problem of the entire world system, including the problem of the entire social science knowledge production as a result, as well as an interpretation, of that world system, including the knowledge production of Sociology.

Recalling my reading and understanding of these writings of his, the first and foremost was of course the World System Theory Volume I. I had read writings by Samir Amin before reading Wallerstein’s World System. My impression, both then and after, was that it gave me better confidence than when reading Amin—Amin’s writing was profound, but it gave me a sort of desperateness, particularly with regard to the relationship between the developed and the dependent / underdeveloped. It made me feel that the South, being dependent on such a system, would be hard put to find opportunities for development. Yet Wallerstein’s World System Theory has put forward a semi-peripheral zone between the core and periphery. That way, first it is at least dynamic and second it gives more importance to the “opportunities” for the peripheral countries within that same world system. Moreover, such a world system theory is not only a structural analysis, but rather a systematic approach for analyzing world issues and problems. It may be referred to as a world system analytical approach. At the same time, it is also an analytical approach for historical sociology. And with this approach, when considering the issues of capitalism and capitalist crises, it would not be performing the so-called “comparative studies” on a country by country basis.

I remember one time at the World Congress of International Association of Sociology in Brisbane, Australia we had both spoken at the forum organized by the Comparative Sociology Committee. He had pointed out that on the aspect of methodology, the original comparison had been based on countries as the unit, comparing country by country, yet in the World System Theory the entire world was treated as one system. It’s just that the system had a core, periphery as well as semi-peripheral zones. Simultaneous to its being a kind of holism analysis, it was also a long duration analysis. The center that Wallerstein had established at University of Binghamton had been named The Fernand Braudel Center, having inherited the academic tradition of Braudel of the French Annales School. It did not simply consider the present or even the recent decades as one unit but would consider the entire capitalist world system as one duration. In this way the several hundred years past are being included in the field of analysis.

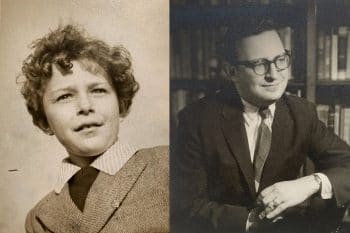

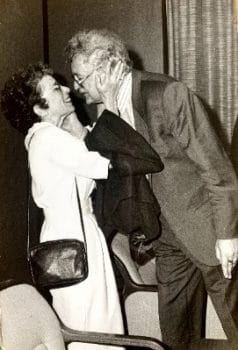

Immanuel Wallerstein (right) and Fernand Braudel (left) at the inauguration of the Fernand Braudel Center in Binghamton University (New York) in 1976.

To me, other than the two analytical methods of World System and long duration, from which I am still benefiting and of which I am still willing to learn more about, I have begun to give more attention to his two other researches since 1995 when I was a visiting scholar in the United States. One was Opening Social Sciences that was later up as a report, and the other was a collection of his own relevant papers and speeches, which he named Unthinking Social Sciences. Of course, there was also the third one which was called The End of the World as We Know It. He had intentionally used this name to differentiate it from The End of History. These three books starting from Opening Social Sciences were in fact written up after long period of research by a group of scholars from different disciplines that Wallerstein had organized. The purpose was to prove that the so-called Social Science since the 18th century was in fact a portrayal of the society since the 18thcentury, as well as a theorization of this society. In this way, the certain “coats” or disguises that social science used to have had been taken off by him. It was not what we had thought, or what people had declared earlier, as being an objective and scientific reflection of the society, like a natural science, but in fact the very consequence and justification of this society. Yet it was at the same time being used to demonstrate and justify the normality of this society. In Unthinking Social Sciences, he had further put forward a fundamental remake, at least a framework for doing so. That was, we might as well regard the social science that was there as problems to be challenged, unthinking it. Finally, in The End of the World as We Know It it was shown that following the end of the Cold War, with the arrival of the new century, the existing social science knowledge system had also been going towards the end!

Linking up these three points, from viewing the world as one entire World System to viewing this World System over the long duration including its changes and finally to challenge, reflect and unthink the so-called Social Science that looks at the world, coming to today with the many uncertainties, crises and risks we are facing, it has indeed shown so much foresight. In his speech in Armenia, at a time when the 2007-08 financial storm had just happened, his had not in fact directly touched on the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the Freddie Mae and Fanny Mae sub-prime crises nor the Wall Street tsunami, but rather that in accordance with the analysis of the world system, the financial storm and economic crisis were a matter of timing. Moreover, it would definitely happen at the core zone, at its financial center, in the zone where industrial capital had already been hollowed out leaving only the virtual capital and a highly financialized bubble economy. The crises in the sense of the holistic world system would happen.

In conclusion, my association with scholars like Immanuel Wallerstein, Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi and so on had really been beyond age or racial differences, entirely exchanges, communication and dialogues among scholars without any consideration or distance on nationality or generation, nor eminence and distinctiveness. They had not put on any airs of celebrities. It was indeed rare and most enjoyable and memorable!

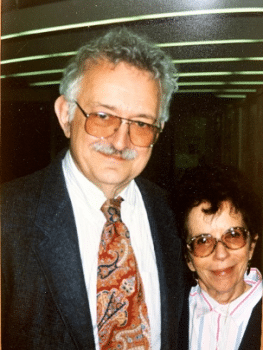

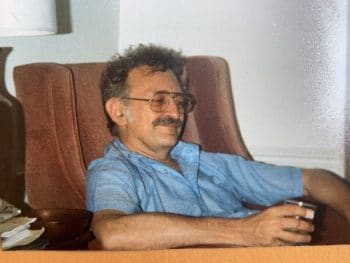

Vancouver, Canada, July 2007. From left to right: Wen Tiejun, Immanuel Wallerstein and Beatrice Wallerstein.

Wen Tiejun (Renmin University of China) [top]

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

On this day of 31 August 2020, the one-year anniversary of Professor Wallerstein’s departure, our rural construction participants as well as the research team that closely integrates with rural construction practice, would like to express our deepest regard to the spirit of esteemed Mr. Wallerstein.

The influence in China of Professor Wallerstein’s thinking has not weakened with his departure, but rather has been viewed with increasing importance. Moreover it has become the key theoretic tool for our project team, being directly applied to analyze the structural contradiction encountered by China since the latter’s entry into the globalization process dominated by financial capital, as well as the unprecedented challenge to China’s export oriented economy arising from globalization’s disintegration due to that inherent contradiction.

We have inherited Professor Wallerstein’s World System Theory and carried it forward with the view that: having been through successive crises since the eruption of the 2008 Wall Street financial tsunami, not only has U.S.A. repeatedly made use of ultra-loose quantitative easing policies to transfer costs of the crises to the rest of the world, it has during this process further instituted the formation of a new financial capital core in 2013, through an on-going currency swap agreement among six western financial capital countries. In 2020, it went one step further to form a semi-periphery of 16 countries. What follows is that other developing countries become peripheral and excluded by financial capital.

I remember that in July 2007 in a face-to-face meeting with Mr. Wallerstein, I had discussed with him questions on the topic of financial capital globalization, how financial capital crises were being transferred to developing countries through the exclusive system established by the core countries dominated by US Dollar. He had listened carefully to the viewpoints I proposed and responded seriously to my questions. It has benefited me greatly at that early phase when I entered the realm of international comparison research.

At this time, the international situation is extremely complicated. After the eruption of the major financial capital globalization crisis, not only does China face the challenge of a hard ‘de-linking’, it may possibly be subjected to ‘de-Sinicization’ in those financial aspects related to international trade. It demonstrates that we can rely on Professor Wallerstein’s World System Theory to explain the further step that financial globalization has already taken, to become financial fascism that is of extreme exclusivity.

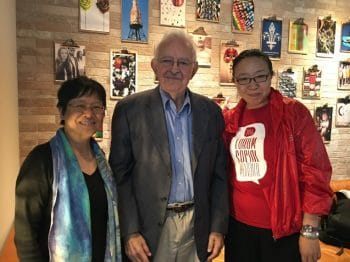

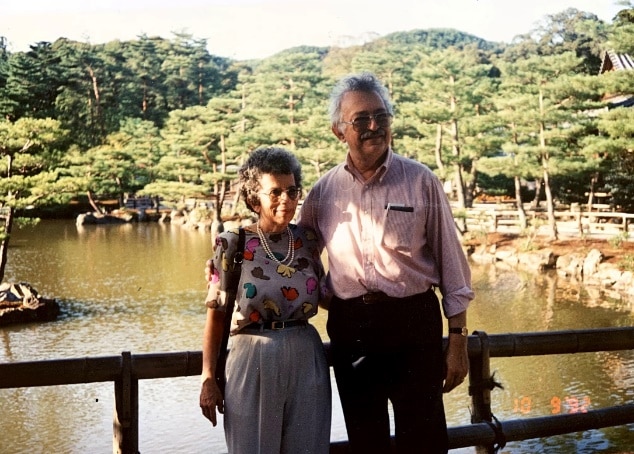

Immanuel Wallerstein and Sit Tsui before an interview for the Global University for Sustainability at the World Social Forum in Montreal (2016).

Sit Tsui (Southwest University, China) [top]

On 9-14 August 2016, Prof Lau Kin Chi led the Executive Team of the Global University for Sustainability (Global U) to attend the World Social Forum (WSF) in Montreal, Canada. It was my first time to meet Prof Immanuel Wallerstein who shuttled between streets and classrooms, sincerely providing social movements with his theoretical weapon of Modern World System.

This was the only WSF held in the Global North. This aroused a lot of controversies. However, Prof Wallerstein still believed that WSF was a convergence for people of the world to gather and discuss the future of social movements. He devotedly defended it with his pen. On 9 August, Global U founding members walked together with Prof Wallerstein in the parade march of the opening ceremony. He was 86 years old at the time, but he walked very steadily and fast.

On 11 August, Alice Chan and I brought a camera to video-record Prof Wallerstein’s seminar. The venue was a small classroom crowded with participants. The moderator mentioned that the theme was about class, race, and gender struggles in the United States. The audience was mainly from social movements. Prof Wallerstein’s wife and granddaughter participated too. He talked for about 20 minutes and made his precise analysis of the global situation and his suggestions for social movements.

Here I make a brief summary: capitalism could not sustain any more as capitalists could not earn more profit from production, and it was also difficult to find more people who could be exploited. People also found that they could not afford to buy commodities. Nowadays capitalism turns to finance, but it means to transfer money but not to increase productivity. Capitalism was doomed to have its structural crisis. It lost its equilibrium, then bifurcation appeared. One fork went towards a new system which was worse than capitalism, the other a comparatively equitable world system. The former we named it the spirit of Davos which upheld hierarchy, exploitation, and polarization; the latter the spirit of Porto Alegre which defended people’s livelihood and fought for social justice. At that crossroad, we must collectively make a historical choice. The spirit of Porto Alegre made the legacy of 1968 alive which allowed an explosion of different kinds of people’s organizations, springing up like mushrooms. They were full of diversities and energy. They were not like traditional leftist movements which were exclusive only to one kind of worker’s movement. We should let 99% represent the diversities of people’s movements but we should also facilitate the unification of 99%. There were short-term, middle-term, and long-term struggles. The short ones should aim to minimize people’s pains and let them survive, even though they did not change the system fundamentally. Let’s learn the theory of butterfly effects. Here, a little butterfly flagged her wings, nonetheless, it changed climate at the other end. We were all little butterflies, but if we gathered and it might become powerful enough to turn the direction, toward a better world. ( “Immanuel Wallerstein on Class Struggle at WSF Montreal, 2016,” produced by Global University for Sustainability.)

After the seminar, I introduced myself: my PhD supervisor was Prof Hui Po Keung (PK), who was a student of Prof Giovanni Arrighi. Prof Hui moderated the Cultural and Social Studies Translation Series (1996–2002). Both Prof Arrighi and Prof Wallerstein were advisers of the translation project. We translated their articles for Chinese readers in the mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

At the end of the 1990s, PK, Kin Chi and Chan Shun Hing had initiated the translation series, with the purpose of introducing leading progressive scholars to the Chinese-speaking world. Afterwards, they met Prof Wang Hui, and they immediately developed a strong friendship. Working together with many scholars from the mainland, they published a total of eight volumes, such as The Illusion of Developmentalism, edited by Hui Po Keung and Wang Hui, Women, Nation, and Feminism, edited by Chan Shun Hing and Dai Jinhua, and Subaltern Studies edited by Lau Kin Chi and Hui Shiu Lun. Meanwhile, through the translation projects, they trained a group of young scholars and students. I had the great honor to join the team and worked as a research assistant. I learned a lot from practical work: translating, vetting, typing, and dealing with matters such as copyrights, postage and delivery.

One year after the passing away of Prof Wallerstein, his last words at that seminar are still lingering in my ears: “Let’s be Butterflies!”

“The Life and Thought of Immanuel Wallerstein, 2016,” produced by Global University for Sustainability

Remy Herrera (University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, France) [top]

It was in 1992, when I was still a student, that I had the honor of meeting for the very first time Immanuel Wallerstein who was then giving a series of conferences within an interdisciplinary seminar taking place physically in the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences sociales (boulevard Rapail in Paris), especially frequented by progressive historians, philosophers or economists. For several years, I had already read—and deeply admired—the entirety of his work and even devoted to his masterpiece, The Capitalist World-Economy, one of my academic works. Happy to finally be able to listen to and see this giant of thought, I followed his Parisian lectures as regularly as possible, always dazzling with culture, knowledge and intellectual power. I remember him as a calm, reserved, elegant man. When it sometimes happened that certain listeners made criticisms of his theses—Immanuel Wallestein’s theses being often courageous and even risky, because they were also forward-looking –, he received these words without the slightest contempt, but with calm, modesty and, it seemed, a hint of disappointment at not having been fully understood as he wished. Subsequently, I had the chance to be able to count on his collaboration for a collective book that I coordinated (L’Empire en guerre, published in French just after the events of September 11, 2001) and to see him again on various occasions, in particular during the fourth edition of the Mumbai World Social Forum in 2004.

Immanuel Wallerstein sought to understand the reality of this historical system that is capitalism so as to conceptualise it globally, as a whole. Whereas Amin’s approach was explicitly an interpretation of the world-system in terms of historical materialism, Wallerstein’s ambition was seemingly the reverse: elements of Marxist analysis were to be integrated into a systems approach. In reality, as Wallerstein made clear, “[o]nce they are taken to be ideas about a historical world-system, whose development itself involves ‘underdevelopment,’ indeed is based on it, [Marx’s theses] are not only valid, but they are revolutionary as well.”

In Immanuel Wallerstein’s works, the world-system perspective is explained by three main principles. The first is spatial—“the space of a world”: the unit of analysis to be adopted in order to study social behaviour is the worldsystem. The second is temporal—“the time of the long time”: world-systems are historical, in the form of integrated, autonomous networks of internal economic and political processes, whose sum total ensures unity and whose structures, while continuing to develop, basically remain the same. The third and final principle is analytical, in the framework of a coherent, articulated vision: “a way of describing the capitalist world-economy”, a singular world-system, as a systemic economic entity organising a division of labour, but without any overarching single political structure.

This is the system that Immanuel Wallerstein intended to explain not only in order to provide a structural analysis of it, but also in order to anticipate its transformation. Its whole force consists in its capacity to conceive the overall structure of the system as one of generalized economy and to conceive the processes of state formation and the policies of hegemony and class alliances as forming the texture of that economy.

For Immanuel Wallerstein, the capitalist world-economy displays certain distinctive features. The first peculiarity of this social system, based on generalised value, is its incessant, self-maintained dynamic of capital accumulation on an ever greater scale, propelled by those who possess the means of production. Contrary to Fernand Braudel, for whom the world since antiquity has been divided into several co-existing world-economies, “worlds for themselves” and “matrices of European and then global capitalism”, according to Immanuel Wallerstein, the European is the only world-economy, constructed from the sixteenth century onwards: around 1500, a particular world-economy, which at that time occupied a large part of Europe, could provide a framework for the full development of the capitalist mode of production, which requires the form of a world-economy in order to be established. Once consolidated, and according to its own internal logic, this world-economy extended in space, integrating the surrounding world-empires as well as the neighbouring mini-systems. At the end of the nineteenth century, the capitalist world-economy ended up extending over the whole planet. Thus, for the very first time in history, there was one single historical system.

Explaining the division of labour within the capitalist world-system between centre and periphery makes it possible to account for the mechanisms of surplus appropriation on a world scale by the bourgeois class, through unequal exchange realised by multiple market chains ensuring control of workers and monopolisation of production. In this framework, the existence of a semiperiphery is inherent in the system, whose economic-political hierarchy is constantly being altered.

The inter-state system that duplicates the capitalist world-economy is, however, always led by a hegemonic state, whose domination, temporary and contested, has historically been imposed by means of “thirty-year wars”. Like those that it succeeded (the United Provinces in the seventeenth century and England in the nineteenth century), the U.S. hegemony established since 1945 will come to an end.

Immanuel Wallerstein paid minute attention both to the cyclical rhythms (the “microstructure”) and the secular trends (the “macrostructure”) operative in historical capitalism, which stamp it with alternating periods of expansion and stagnation and, above all, to recurrent major crises: historically, capitalism entered a structural crisis in the first years of the twentieth century, and will probably experience its end as a historical system during the twenty-first century.

Immanuel Wallerstein, A major world thinker for another possible world, for a better world

Gustave Massiah (Centre de recherche et d’information sur le développement, France) [top]

Immanuel Wallerstein has left us one year ago, we feel great sadness and emptiness. It is a great distress to think that we will no longer be able to discuss and debate with one of the persons we were closest to intellectually and who meant so much to us.

Immanuel represented the best imaginable figure of the committed intellectual, in the line of the great intellectuals who gave their letters of nobility to scientific, cultural and political thought. He was first and foremost a great philosopher. His philosophy was nourished by his knowledge of the social sciences to which he had contributed and in which he excelled. As an economist, he extended the Marxist approach and participated in its renewal. As a historian, he navigated through long history and had created the Fernand Braudel Centre at the State University of New York at Binghamton. As a sociologist, he was attentive to the evolution and understanding of societies and had chaired the International Sociological Association from 1994 to 1998.

Immanuel was an outstanding teacher. He did not impose his lessons. He had that rare quality of daring to think aloud for his auditors. His lectures and seminars were moments of great creativity; they allowed us to go deeper, to cross approaches, to always hold on to realities. We always discovered new proposals, plunged into History, reasons to get involved. He also knew how to galvanise large audiences. I remember, at the United States World Social Forum in Detroit in June 2010, the lively discussions lasting several hours with an enthusiastic audience of hundreds of young people sitting on the floor.

Immanuel had been part of the Braudelian adventure in the history of capitalism. He shared with Fernand Braudel a passion for long time and the “grammar of civilisations”. Fernand Braudel, in one of his last interviews with Thierry Paquot who mentioned his disciple Wallerstein, was surprised and said: but Wallerstein is not my disciple, he taught me more than I brought him. It was Immanuel who best knew how to combine the Braudelian approach of the long time with the approach and the questions coming from Marxism. He proposes a very founding concept, that of the world-system, which broadens and completes Braudel’s proposal of the world-economy. We can find, with interest, his analysis of the capitalist world system in Understanding the world, analysis of world system (Comprendre le monde, analyse des systèmes mondes, Ed. La Découverte 2009). He offers a presentation of the beginnings of capitalism in Capitalism and world economy (Capitalisme et économie monde 1450-1640, Ed. Flammarion 1980). He wrote a synthetic and highly pedagogical approach in Historical capitalism (Le capitalisme historique, Ed. La Découverte 1985).

Immanuel was not only interested in the birth of capitalism. He became passionate and committed to the fight against capitalism, questioning the end of capitalism. Having studied the beginning of capitalism in the history of civilisations, he had no doubt that capitalism would come to an end. His hypothesis was that we have entered a deep structural crisis that will not be resolved by a new phase of capitalism. He believed that a new mode of production would succeed capitalism in the next thirty or forty years. But he stressed that, although the end of capitalism is historically certain, it does not automatically lead to the arrival of an ideal world. He thought that a new “post-capitalist” mode of production could be unequal. He saw the possibility of several bifurcations: « the one leading to a non-capitalist system retaining from capitalism its worst characteristics (hierarchy, exploitation and polarisation), and the one laying the foundations of a system based on relative democratisation and relative egalitarianism, i.e. a system of a type that has never existed before ».

What allowed Immanuel to broaden his horizon and situate his analyses and his world systems on a global scale was his understanding of the fundamental historical character of decolonization. He was involved in decolonization, as illustrated by his early works: Africa and Independebce (L’Afrique et l’indépendance, Ed. Présence africaine, 1966) and Inequalities between states in the international system (Les Inégalités entre les États dans le système international : origines et perspectives, Ed. Centre québécois des relations internationales, 1975). He was very attentive to the dependence school and to analyses articulating ‘center and periphery’ in the analysis of the long period.

From the beginning of the 1980s, he was present in a succession of meetings and seminars, initially in Dakar, at the initiative of Samir Amin, with committed intellectuals from Africa, Asia and Latin America. This approach was part of the process for the autonomy of a decolonial way of thinking; it was extended in the world social forums. He participated in the group formed by four historians and economists (Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, André Gunder Frank and himself) claiming the appropriation of long history from the periphery and the anti-colonial struggle. This led to two books: The crisis what crisis (La crise, quelle crise? Ed. Maspéro 1982) and The great tumult ? social movements in the world economy (Le grand tumulte ? Les mouvements sociaux dans l’économie-monde, Ed. La Découverte, 1991).

At the turn of the 2000s, Immanuel was one of the thinkers of the alterglobalist movement. He took a very active part in it by bringing a vision, nourished by his research and commitment, characterised by a dialectical approach. He was concerned to situate the movement within a historical dynamic while paying great attention to contradictions and counter-tendencies. He gave particular importance to what he defined as an anti-systemic movement opposing the dominant logic. He conceived the process as a movement that starts from the class struggle and expands it. For him, in each historical period, the main classes are antagonistic, but they form class blocks with alliances that oppose the movement leading the system with the anti-systemic movement opposing it. He left us a method which has the advantage of not restricting social analysis and history to economic confrontations and that leave room for ideological, cultural and political dimensions. On these essential dimensions, Immanuel published one of his most striking books: European universalism, from colonisation to the right to interfere (L’universalisme européen, de la colonisation au droit d’ingérence, Ed. Démopolis 2008), which deconstructs the pretentions of the dominant ideology to capture universalism.

At the same time, he organised, with Etienne Balibar, a seminar in Paris at the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme which lasted three years, from 1985 to 1987, around the theme Race, Nation, Classe (hence the book Race, Nation, Classe, les identités ambigües, Ed. La Découverte 1988, republished in 2007). This materialist approach is still very relevant today on the need to broaden the class struggle by taking into account other dimensions, notably the gender issue which has emerged as an essential question over the last thirty years.

Immanuel attached great importance to cultural revolutions. He considered that there was a break that had begun with the ideological disruptions visible in the world in the 1968s. Over and above the counter-revolutions, he linked the ideas that broke out at that time with the alterglobalist movement, with the women’s right movement, with the ecological movement and with the cities square movements from 2011 on. He considered that the violence of the ideological, geopolitical and military reactions showed the importance of the changes that were in the making. Historical periods do not follow one another in a clear-cut manner, they interpenetrate and combine over a long period of time. The History of the future is not written and we must be attentive to what comes up again. Immanuel listened to the new world and he always did so without losing a great sense of humour. He had answered one day in a debate that we had in Porto Alegre that he completely shared the analysis of Occupy Wall Street on the 1% and 99%, but that we should not forget that 99% was not enough to make a majority!

Immanuel engaged himself by closely following the news. Since 1 October 1981, he published a monthly commentary that was fairly short and punchy. He had decided to stop a few months ago after publishing his 500th Commentary in which he estimated that there was a 50% chance that the transformations of the 1968s would lead to more democratic and egalitarian positive transformations. And he concluded: there is only a 50% chance, but there is at least a 50% chance.

In the long 23-page preface he wrote for the English version of my book written in collaboration with Elise Massiah, An alterglobalist strategy (Une stratégie altermondialiste, Ed. Black Rose Books in 2013, based on Ed. La Découverte in 2011), he explains the importance of the alterglobalist movement. He points out that the movement is a break with the theory of taking power that has long dominated anti-systemic movements: first to conquer state power, then to change society. He concluded that it is necessary to start from the action of each individual to change the course of events. The smallest contribution, such as the flapping of the wings of a butterfly at the other end of the world that is part of the storm that is coming, is necessary, indispensable, he said. There are no “small” struggles, no “small” resistances. There is a disparate set of actions and interventions that sometimes (but not always) converge to force “big” changes. This collective and continuous action is the decisive element for “building another possible world, a better world”.

Wallerstein expanded the South African independent left’s horizons

Patrick Bond (Professor of government, University of the Western Cape) [top]

In introducing The Essential Wallerstein, Immanuel Wallerstein wrote,

I credit my African studies with opening my eyes both to the burning political issues of the contemporary world and to the scholarly questions of how to analyze the history of the modern world-system. It was Africa that was responsible for challenging the more stultifying parts of my education.

I initially thought that the academic and political debates were merely over the empirical analysis of contemporary reality, but I soon became aware that the very tools of analysis were themselves to be questioned. The ones I had been taught seemed to me to circumscribe our empirical analyses and distort our interpretations.

Slowly, over some twenty years, my views evolved, until by the 1970s I began to say that I was trying to look at the world from a perspective that I called ‘world-systems analysis.’

This was the spirit Immanuel retained during visits to South Africa in 2006, 2009 and 2011, as the independent left here matured and found opportunities to draw him into academic and activist events, so as to back up our critiques of the country’s increasingly neoliberal government and notoriously super-exploitative capitalist class. During each trip, visiting the country’s three main cities and leading universities, he showed us how our local and global linkages of liberatory political projects were in need of strengthening, beyond the empirical and into broader ways of thinking and acting.

Immanuel Wallerstein and Beatrice (center, third and second rows) at the University of Johannesburg Centre for Social Change, November 2010.

Four independent left scholar-activists—Trevor Ngwane, Kate Alexander, Mary Galvin and Ashwin Desai—who knew him well can testify to this:

Comrade Immanuel Wallerstein’s writings opened my eyes and those of many comrades to the international nature of the capitalist and imperialist system of exploitation and oppression. He showed its historical development and the various mechanisms it uses to subject the world’s peoples and working classes to its totalising power. This insight was very important in the struggle for national liberation because it facilitated the building of revolutionary national movements against colonialism informed by anti-capitalist pro-socialist vision. Anti-imperialism became the hallmark of any liberation movement worth its salt.

Today Wallerstein’s lessons are as important as ever as humanity struggles to cope with the economic and ecological ravages of the global capitalist crisis. They point to the need for the world’s working classes and allied social forces to unite within and across national borders in order to match the international power of capital. We are struggling to eradicate all forms of exploitation and oppression. The only viable and lasting solution is to overthrow the capitalist world system and replace it with socialism on the road to communism.

On a personal note, I remember in 2011 he came to Soweto to visit the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee and we showed him how to reconnect the electricity [disconnected by state authorities] in one house. It was fun and the comrades really liked him and he enjoyed himself. He was in full support of our method of commoning the electricity.

—Trevor Ngwane, Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Johannesburg and 2020-21 President of the South African Sociological Association

So many happy memories of Immanuel, who visited us at the University of Johannesburg several times. He gave a talk to our senior students—‘From doctoral research to World Systems Theory’—which turned into a spellbinding intellectual autobiography that rooted his development in African experience, and made the students feel bigger, with a future beyond their dissertation.

On another occasion we took him to Soweto where he participated in removing a household water meter, so that a poor family could receive free water. He wasn’t bothered that this was illegal and loved having his photograph taken with the activists. It was a little contribution to struggle.

—Kate Alexander, Professor of Sociology and Director of the Centre for Social Change, University of Johannesburg

First and foremost, Immanuel was an intellectual, as evidenced by a library collection full of his prolific publications translated into many languages. His exceptionality was his commitment to making himself and his ideas available to activists to feed the class struggle.

From World Social Forums to conferences across the globe, his travel schedule was always full, well-managed by his intellectual partner and wife Beatrice. When he was in South Africa, I remember Immanuel giving lectures to academics and activists, joining in marches and spending his free time with comrades, reflecting on what the past teaches us about our present struggles and strategies.

We knew him as a generous, wise and kind elder, showing his amusement with a sly smile. When I visited him a couple months before his death, he was determined to achieve his aim of producing the 500th of his Commentaries. Indefatigable?

In his final broadcast he wrote: ‘Because of the structural crisis of the modern-world system, it is possible, possible but not absolutely certain, that a transformatory use of a 1968 complex will be achieved by someone or some group… I have indicated in the past that I thought the crucial struggle was a class struggle, using class in a very broadly defined sense. What those who will be alive in the future can do is to struggle with themselves so this change may be a real one.’

—Mary Galvin, Associate Professor of Development Studies, University of Johannesburg

Immanuel’s collaborations with Etienne Balibar on race and nationalism were pathbreaking, with case studies of southern Africa including Angola and South Africa. Here, he challenged the idea of ‘two stages’ [i.e., first we should end apartheid, then later end capitalism]. He did so seriously, subjecting it to sympathetic critique, not agreeing with the formulation, thereby joining many of us who didn’t, including myself.

But in this triangle of class, race and nation, we had a magical idea during the 1980s, of what class politics could do. I think we underestimated how powerful the ideas of race and nation are, and how much they trespassed into the ANC. The limitations of national liberation are obvious, but Wallerstein brought to bear his experiences and was much more sober in reading into South Africa’s trajectory the Trojan Horse of nationalism, as much as one would the Trojan Horse of the Stalinism that has been so prevalent in communist politics here.

One of the most haunting comments he made to me related to two of our institutions of the scholarly left: the Centre for Civil Society at University of KwaZulu-Natal and Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg. He told us when we were under pressure at these two sites, that in his own experience in the U.S. and Latin America, these kinds of places are cherished institutions but you can lose them, and if you do, you can never get them back.

—Ashwin Desai, Professor of Sociology, University of Johannesburg

Immanuel Wallerstein and Beatrice (center, third and second rows) at the University of Johannesburg Centre for Social Change, November 2010.

What Ashwin partly refers to, at the Centre for Civil Society (CCS) in South Africa’s third city, the port of Durban—a praxis-oriented research/teaching institute which I directed from 2004-16—was not only Immanuel’s regular lecturing. Also, his endorsement of CCS in mid-2008 was instrumental in fending off the centre’s threatened closure, in the course of a political attack from a rightwing University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) administration. CCS was UKZN’s “single most prestigious activity”, Immanuel wrote, and “the jewel in its crown. Those of us who try to follow what is going on in South Africa have come to rely upon CCS as the best single source of wide information. Closing it down would not only damage severely UKZN’s reputation but would set back research worldwide on contemporary South Africa.”

Immanuel would deliver profound talks, sometimes in intimate seminar mode on the South Durban beachfront with post-grad students. On another occasion, in mid-2011, he spoke about the North African uprising and U.S. imperialism to an audience of several hundred activists, proletarians and the urban poor, along with the smattering of progressive petit-bourgeois intellectuals you find at places like UKZN (whose role in ruling-class reproduction survived the democratic transition). In 2006 he was at CCS to debate Samir Amin on the World Social Forum, where his optimism was contagious. He was especially important to a 2009 conference on ‘the commons’ which he keynoted alongside the late Ugandan Marxist Dani Nabudere, local revolutionary poet-activist Dennis Brutus (in his last public appearance) and U.S. ecologist Hazel Henderson. There, the basis for South Africa’s contributions to eco-socialist-feminist theory became better grounded in our grassroots comrades’ successful efforts to decommodify AIDS medicines (raising life expectancy rapidly from 52 to 65 today); to eventually gain free university education; and to ensure many townships gained energy and water supplies even if they could not afford increasingly-corporatised municipal systems (hence the illegal service-reconnection tactics that Trevor refers to above, and that delighted Immanuel when he learned 86% of Sowetans were not paying for electricity).

Immanuel’s prestige in these academic events was quickly shaken off when he traveled through low-income townships, visited Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram (from the period during a 1894-1913 on-and-off Durban residence) and ventured into South Africa’s many recreational sites. Immanuel created space to rejuvenate with friends. In 2009 he visited Bushmen rock paintings in the Drakensburg Mountains with Mary and her children, helping to carry baby Kati up steep hills and teaching Cameron chess. Mary remembers a scare when no one had brought snacks and his wife Beatrice worried about his blood sugar (he was diabetic). Keeping his schedule manageable and encouraging him at each step in the itinerary to add rest and recreation, she possessed enormous power. And her intellectual partnership was also abundantly evident. Moreover, Beatrice’s care for maintaining South African friendships was always the most magnanimous of any visitor I can recall.

Eddie Webster, the longest-serving radical sociologist in South Africa, has great memories of Immanuel’s visit: “On one of his visits to Wits University I took him down the ERPM gold mine in Boksburg, east of Joburg. He was fascinated especially when I explained how the rockfalls turned men into paraplegics. It was memorable for us both.”

The last time I spent time with Immanuel was in 2017 when Nancy Fraser gathered a network together, not far from his Paris apartment, to contemplate a ‘triple-movement’ (post-Polanyian) strategy, in part to combat the capitalists’ ‘lean-in feminism’, market-centric ‘ecological modernisation’ and the kind of South African-style Black Economic Empowerment in which parasitical firms assimilated the likes of our current president, Cyril Ramaphosa. Immanuel was, as ever, wry and engaged. And in all my subsequent communications, he replied rapidly when asked for the latest advice he had, on combining analysis and praxis aimed at both world-scale top-down structure, and bottom-up struggle.

Not that there weren’t open-ended debates and disputes, such as whether the semi-periphery represented a ‘sub-imperial’ layer, one that worried other great global theorists including Ruy Mauro Marini in the 1960s-70s and David Harvey in the early 2000s. The old question of whether world-systems was supplemental—or in opposition to—the theory of uneven development regular confounded us. But in establishing a strategic approach to these big-picture problems, which we continue to face in South Africa, no one I know embraced scale-politics better, with more seriousness and historical reach, and with such a long-range, compassionate future viewpoint, than Immanuel.

Immanuel Wallerstein, a Belated Farewell

Boris Kagarlitsky (Institute of Globalization and Social Movements, Russia). Originally published: Counterpunch, October 10, 2019. [top]

Translated from Russian by Natasha Minkovsky.

Alas, I have not written about Immanuel Wallerstein right after his death, as I should have. The electoral campaign for Moscow City Duma demanded all my time and attention, so I limited myself to a short post on social media and promised to write an article later.

Now, after the election has come and gone, the time has come to deliver on my promise.

Of course, Wallerstein deserves not just a column, not even just an article, but a major biographical study. Everybody still remembers him as a living classic, a maître of historical sociology, but for a better understanding of his intellectual journey we should return to its very origins–to the 1960s, when a young American sociologist was trying to answer the question: what is not right with the development of the African countries?

From the beginning, many predicted a great future for Wallerstein. He secured a brilliant academic career starting as an instructor at his alma mater, Columbia University, in 1959, immediately after receiving his doctorate degree at the age of 29. Then, the young researcher surprised his colleagues and supporters: he concluded that the modernization theory which he was taught, and which he set off to develop further, is not correct. Worse than that, when student unrest started in New York in 1968, as it did throughout the world, he joined the rebels and became one of their ideologues.

Modernization theory, which was popular in the West in the 1950s, was bourgeois interpretation of the Soviet experience of industrial development during the 1930-40s. As a matter of fact, it reproduced an orthodox Marxist concept formulated by Karl Kautsky and G.V. Plekhanov. According to these views, all countries go through the same stages of development. It is impossible to skip a stage, but the experience of the more developed countries can be used to accelerate the process. If a country is currently in a feudal stage, a bourgeois revolution is needed to create the conditions for a welfare state, which, in turn, would allow a transition from capitalism to socialism.

In the modernization theory framework, transition to socialism was, naturally, not an issue, and thus a different terminology was used: the place of “capitalism” and “socialism” was taken by the “industrialized society.” Western countries served as a model of such society; however, an alternative—the Soviet model—was also acknowledged. One way or another, the developing world was prescribed a consecutive set of measures, institutions, and technologies, so that after passing several stages, they could join the “civilized world” and create a “normal” modern society. It is clear now why Soviet sociologists who preached Kautsky’s paradigm as a basic principle of Marxism-Leninism easily transitioned in the 1990s into a specific version of the modernization theory, according to which Russia should stop socialist experiments and return to the “main path of development” by joining the West, which was now not just the best kind of an industrial society, but the only possible one. The problem is that the unsoundness of this idea was demonstrated by Wallerstein and his followers in the beginning of the 1970s.

Strictly speaking, Kautsky’s concept was already overturned by the Russian revolution in 1917 which, according to his views, could not happen, or at least could not be socialist. Antonio Gramsci was the first to notice this. He called it the revolution against “Capital,” while Kautsky could never bring himself to accept this event which overturned his harmonious theory.

On the contrary, Soviet ideologues after Lenin’s death not only stayed loyal to Kautsky’s ideas despite their own historical experience, but also turned them into a dogma. This is not surprising: such a scheme is easy to teach and to accept.

Meanwhile, in the beginning of the 20th century, Rosa Luxemburg and Mikhail Pokrovskiy already showed that capitalism develops not as a sum of national economies which live and progress side by side, but rather as a unified system where “underdevelopment” (“backwardness”) of some and the “successful development” of the others are, as a matter of fact, interconnected, and cannot exist without one another. Moreover, the issue lies not only in the exploitation of colonies, but in the complex logic of the system, within which the center and the periphery develop spontaneously. Wallerstein went further, showing how the process of capital accumulation within such a system naturally creates a tendency to redistribute resources and benefits from the periphery to the center.

Having already published the first volume of his main work, “The Modern World-System,” Wallerstein demonstrated that capitalism first emerges as a global economic system, and only then are “national capitalisms” formed within it. As for the countries of the periphery, all sorts of manifestations of backwardness become not only a “brake for development,” but also a kind of competitive advantage, which the elites of these countries use in order to fit into the world system more effectively: slave labor allows the production of cheap goods, the absence of an independent court and universal corruption is a way to simplify investment processes, hired killers are cheaper than lawyers, etc.

Leaving Africa, the British and French colonizers left behind almost the full range of democratic institutions in most countries—parties, courts, and parliaments, but almost nowhere has it been possible to maintain this democratic order in the conditions of independence. Unlike those who attributed the events to the cultural or racial backwardness of the “natives,” Wallerstein realized that these were systemic limitations. By and large, the full spectrum of all democratic freedoms, rights, and institutions is only necessary in the countries of the core. For the periphery, these rights and freedoms are redundant regarding the interests of capitalist accumulation. Furthermore, even if they are available, they limit bourgeois development rather than stimulate it. They are not generated by the capitalist order but rather are imposed on the ruling class by social resistance or by the balance of the internal societal forces.

The political conclusions that stem from the world-systems theory may seem pessimistic at first glance: it is, at the very minimum, difficult to break the system and build a new society in one single country. The Soviet revolutionary burst, despite its grandiose achievements, ended with the restoration of capitalism. In the 1990s, Wallerstein established the fact that all three alternatives to the bourgeois order that arose in the 20th century—the communist movement, social democracy, and the national liberation movements of the countries of the periphery—all were equally defeated.

This, however, does not mean that the capitalist world system is invincible. On the contrary, no matter what condition its adversaries are in, it faces internal contradictions that inevitably undermine its stability and ultimately doom it to a collapse once its historical potential is exhausted.

The logic of universal global engagement has not only a dark side but also a bright side. Any revolution in the capitalist world already reflects not only the level of development of the productive forces in a single country, but to a certain extent, in the entire world-system and in the global bourgeois economy. Any national revolution is a factor in changing the nature of not only a single territory’s development, but also of the entire system. In this regard, modern capitalism is a product of the Russian Revolution and Soviet industrialization, Chinese communist experiments, and anti-colonial uprisings in the Third World not less, but perhaps even more than of the processes occurring in Western industrial countries.

As early as the late 1990s, Wallerstein forecast the impending decay and demise of the capitalist world-system, which he predicted to happen in the next half a century. What new world-system will replace it, the researcher stated, depends on many circumstances. It hasn’t developed yet and we can’t say in advance what it will be like. We can’t even say in advance that it will be better. The only thing we know for sure is that it will be different.

The last time I had the opportunity to talk to Wallerstein one-on-one was during the social forum in Porto Alegre, where we happened to encounter each other near a table with a book display. We drank coffee and talked about the future—is there a chance for a revival of the left movement in the coming years? What would it be like?

At that time, Wallerstein was finishing the fourth volume of his fundamental work. After three previous volumes, which have become classics, the continuation was met with respect and interest by colleagues, but without much enthusiasm—all the main ideas of the work were already formulated in the previous sections.

The last, fifth volume dedicated to the era of anti-bourgeois revolutions remained unwritten. There is some symbolism in this—many great texts of the social and political sciences, including Karl Marx’s “Capital” and Lenin’s “State and Revolution” remained unfinished. Research and transformation of society has no predetermined limit, much less a predictable result. History should not only be studied, but also created.

The question of how the crisis of the capitalist world system will turn out for humanity and my country and what will replace it is not purely theoretical. The answer to this question is up to us, those who live and act in our crucial era.

Immanuel Wallerstein: In Memoriam

Boaventura de Sousa Santos, University of Coimbra, Portugal. Originally published: Znet, September 2, 2019. [top]

The death of Immanuel Wallerstein is an irreparable loss for the social sciences. He was unquestionably the most remarkable American sociologist of the twentieth century, and the one with greater international projection. His major accomplishment was to inspire successive generations of sociologists to discard the unit of analysis in which they had been trained (national societies) and rather focus on the world system (world economy and the sovereign state system). Following insights of Fernand Braudel, Wallerstein believed that the increasing dependencies and interdependencies within the world system turned it into an unit of analysis capable of generating better working hypotheses for the study of the national societies themselves. Such an analytical break was largely misunderstood in the USA. However, being a global intellectual who was familiar with the social sciences in various languages, Wallerstein was hardly affected. He consorted with almost all the leaders of the liberation movements against colonialism before and after the independences, and set up projects with social scientists of those countries to help build new scientific communities. Let us recall just one particular case: the Center for African Studies of the then recently founded Eduardo Mondlane University, whose director was Aquino de Bragança. Wallerstein was a sociologist fully committed to the fate of the world and, above all, to the fate of the more vulnerable populations, whose liberation, he believed, would be possible only in a post- capitalist, socialist society. That is why he was always there with us in the World Social Forum, from 2001 to 2016. The latter date was when we both were together for the last time.

His scientific stance made him question Western, Eurocentric thinking as a whole—one of our many affinities. It still moves me to remember, when we first met in Coimbra, the generous appraisal he made of a little book on epistemology I had just published: Um discurso sobre as ciências (1987). He immediately offered to have it published in Review, the prestigious journal of the Fernand Braudel Center, of which he was Director, at the New York University-Binghamton. Soon after, he chaired a large international project concerned with anti-Eurocentric epistemologies, funded by the Gulbenkian Foundation, and which he titled “To Open the Social Sciences”.

The relations of Immanuel Wallerstein with the Center for Social Studies (CES), of the School of Economics of the University of Coimbra, were wide and far reaching. One of our researchers and faculty, Carlos Fortuna, had already earned his doctorate at Binghamton under his supervision. During one of Wallerstein’s visits to CES we amply discussed the relevance of the concept of semiperiphery to characterize countries like Portugal. We realized that Portugal, like other countries in Europe, had features that distinguished them from other countries in other continents. Herein started our work to reformulate the theory of the semiperiphery in order to adapt it to our reality. The outcome was one of the most fruitful ways of analyzing Portuguese society. That is why we proposed that University of Coimbra take the honor of granting Immanuel Wallerstein an Honorary Degree in 2006.

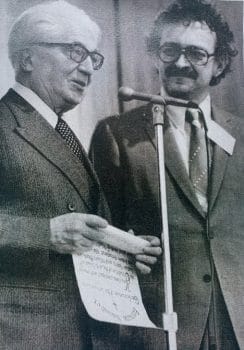

Honorary degree for Immanuel Wallerstein, Coimbra University, 2006

The best way to honor Immanuel Wallerstein’s memory is to carry on with our work bearing in mind the enthusiasm, the professionalism, and the brilliant manner in which he managed to combine scientific objectivity and commitment to the damned of the earth—a stance he never failed to impress on us.

A worthy ancestor

Ari Sitas (Chair of the National Institute for Humanities and the Social Sciences, South Africa). Originally published: Africa is a Country, November 11, 2019. [top]

The world is out of joint and Immanuel Wallerstein, one of its great public intellectuals, has left us—albeit with tools to battle the dying kicks of capitalism.

Immanuel Wallerstein passed away long before another world was made possible. His hope that somehow—out of this final crisis of the world’s capitalist system—another world would emerge, still hangs in the air. For those of us who worked closely with him in the last two decades (in the International Sociological Association and with the project The World is Out of Joint), his mentoring will be missed. It was in and through his stewardship that saw me lead a wonderful ensemble of sociologists to produce Gauging and Engaging Deviance 1600-2000 in 2013. Last but not least was his his support and contribution in constructing the Charter for the Humanities and Social Sciences in 2011 in South Africa, which in turn spawned the National Institute for the Humanities and the Social Sciences.

I was fortunate to be elected president of the South African Sociological Association in 1996, during Wallerstein’s tenure as the president of the International Sociological Association. It thrust me onto the global stage thanks to his Regions initiative. It allowed me to work closely with Teresa e Cruz Silva to gather Southern African sociological voices and allowed us to meet wonderful Latin American scholars, such as Anibal Quijano and Raquel Sosa Elizaga. My first tentative step in India was also thanks to him. Our host was non-other than TK Oommen, who is now being forced to submit his CV to the fundamentalist authorities of the JNU administration to keep his Emeritus status. It was in turn TK Oommen, Hermann Schwengel and I who created the tri-continental Global Studies Masters Program. My indebtedness to him runs into reams of paper.

Many of us after all owe to him the privilege of going global and local, even though we got lost often, in-between.

Most important was his contribution to, in his language, the vital anti-systemic movements of the late 20th century: African and Latin American national liberation movements; their successes and failures their limits and possibilities. Although he was fond of Frantz Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, Julius Nyerere and Aquino de Braganza, the Mozambican scholar and activist, he was gentler in his critique of the aspirant national bourgeoisies on the continent. Whereas for them the failures were subjective and a question of the wrong choices that led to neo-colonial nightmares, for Wallerstein they were objective, a product of world systemic situations that created insurmountable obstacles to choice. This idea he carried over to his assessment of South Africa’s ruling party, the ANC, in the late 1990s.

Later on, he was to embrace with open arms the varied movements that came to constitute the World Social Forum and see in their variety a strength that ought not be abandoned. They were about the substance of an alternative as opposed to formal politics that were only defensive reactions to a weakening status quo. In this he kept the spirit of world-historic moments alive— 1848, 1968 and 1994—revolutions that failed but that have changed the world. The year 1994 although generous to South Africa has its jury still out of court, the dismantling the last race autocracy in the world has led to a serious impasse. We just hope that Wallerstein was right and that the proliferation of racism and authoritarian restorations everywhere are but the final kicks of a dying donkey.

What was Wallerstein’s contribution? That a world capitalist system was in creation since European foraging and settlement; slavery and the construction of race were key to its creation; that the industrial revolution was not a “virgin birth” but a consequence of it; that the system was defined by cores and peripheries; that this system of endless accumulation has its booms and slumps; that European hegemony established a system of inter-state relations; that labor, social and anti-colonial movements have been the animus of change; that we are living through a final crisis that is by now insoluble within a capitalist carapace; that Eurocentrism and the disciplines that were created in and through European hegemony (and colonial and imperial networks of power) have outlived their fictions; that we need to open up the social sciences and make them serve an array of human forms of flourishing.

But the world is out of joint! In Wallerstein’s words:

Who will win this battle? No one can predict. It will be the result of an infinity of nano-actions by an infinity of nano-actors at an infinity of nano-moments … But this uncertainty is precisely what gives us hope. It turns out that what each of us does at each moment about each immediate issue really matters … This is an intellectual task, a moral obligation, and a political effort.

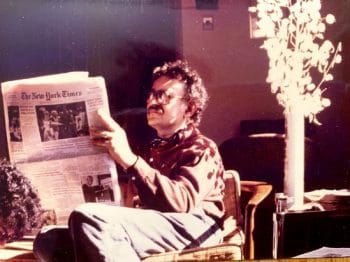

Immanuel Wallerstein during an interview in his office at Yale University, April 20, 2015. Photos by Brennan Cavanaugh, Immanuel Wallerstein shoot stills for David Martinez interview, Yale, 4/20/15.

How Africa shaped Immanuel Wallerstein

Noah Tsika (City University of New York, USA). Originally published: Africa is a Country, August 6, 2019. [top]

Africa and its peoples were central to the great Immanuel Wallerstein’s intellectual development and political activism.

In a reflective essay about his career written in 2000, Immanuel Wallerstein—the American sociologist, economic historian, and world-systems analyst, who died at 88 on August 31 at his home in Connecticut—wrote that “it was Africa that was responsible for undoing the more stultifying parts of my educational heritage.”

Wallerstein, who grew up in New York City and went to Columbia University, wrote about how, in 1951, he attended an international youth congress, and there met many delegates from Africa, “most of whom were older than I and already held important positions in their countries’ political arenas.” The following year, he traveled to Dakar, Senegal for another youth congress. “Suddenly, at this early point, I found myself amidst the turmoil of what would soon be the independence movements (in this case of French West Africa).” The result was that Wallerstein “decided to make Africa the focus of my intellectual concerns, and of my solidarity efforts.”

Surprisingly, this part of his biography has been marginalized in obituaries of Wallerstein. He ended up writing a PhD dissertation that compared the Gold Coast (Ghana) and the Ivory Coast “in terms of the role voluntary associations played in the rise of the nationalist movements in the two countries.” He would remain involved in the academic field of African studies for at least the next two decades, becoming president of the African Studies Association in 1973, at a tumultuous time for that organization. Ultimately, he authored several important books on African politics and economics.

Over time, Wallerstein shifted from African studies to interrogate the workings of capitalism more globally, but as he wrote in that same essay, “I have since moved away from Africa as the empirical locus of my work, but I credit my African studies with opening my eyes both to the burning political issues of the contemporary world and to the scholarly issues of how to analyze the history of the modern world system.”

In 2005, Wallerstein wrote in his book Africa: The Politics of Independence and Unity:

[H]aving emerged from colonial rule, Africa is determined to be subject to no one but itself. The depth of its sensitivity to outside control, the suspicion of outside links, should not be misinterpreted, however. It is not a rejection of the world. It is an embrace of it. For African nationalists held, as one of their cardinal criticisms of colonial rule, that it maintained Africans in a cocoon, that the colonial administration hindered contacts with, even knowledge about, areas and peoples outside the particular network.Wallerstein observed among post-independence Africans “a strong desire to taste the forbidden fruit, to…enter into relations with all those parts of the world somehow previously withheld from [them].” Wallerstein’s earliest contributions to African studies may have overstated this “withholding,” however. For it was (and remains) in the nature of global capitalism to expand beyond any number of borders, both political and discursive. For instance, the Hollywood film industry, in its various forms, had not been “withheld” from Africa prior to independence; its colonizing power was apparent on the continent as early as the 1920s, and it can be seen today in the dominance of Marvel movies in multiplexes from Lagos to Cape Town. Other agents of extractive capitalism—oil and mining companies chief among them—also “entered into relations” with Africa well before the acceleration of decolonization, bringing with them all manner of cultural forms and social practices. The fruit that Wallerstein had (and kept) in mind was, then, mostly monetary—a matter of profits withheld, of resources reliably siphoned away.

As Wallerstein once observed, “the market has been rigged against competition by states and by custom,” and nowhere is this more apparent than on the African continent. Considered in aggregate, Wallerstein’s decades-spanning research offers an indispensable periodization of Africa’s victimization by, and conflicted internalization of, those aspects of the capitalist world-system that Wallerstein himself did so much to limn. He helpfully identified three distinct phases: 1750–1900 (an epoch dominated by merchant capital); 1900–1975 (characterized by the rise of automobility and petro-chemical industries, with merchant capital increasingly forced to operate alongside industrial-investment capital); and the period after 1975, which Wallerstein, writing in 1976, could only sketch in hypothetical terms, and through recourse to then-emergent discourses of postcoloniality.