Contributor Index

- Lau Kin Chi (Lingnan University; Global University for Sustainability)

- Wang Hui (Tsinghua University, China)

- Wen Tiejun (Renmin University of China, China)

- Huang Ping (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China)

- Dai Jinhua (Peking University, China)

- Lu Aiguo (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China)

- Sit Tsui (Southwest University, China)

- Wang Ping (China Society of Economic Reform Journal Agency, China)

- Yan Xiaohui (Global University for Sustainability, Hong Kong, China)

- Muto Ichiyo (People’s Plan Study Group, Japan)

- Alexander Buzgalin (Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia)

- Gustave Massiah (Centre for Development Research and Information, France)

- Michael Hudson (Institute for the Study of Long-Term Economic Trends, USA)

- Patrick Bond (University of the Western Cape, South Africa)

- Paulo Nakatani (Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil)

- Pedro Páez Pérez (The Central University of Ecuador, Ecuador)

- Víctor Hugo Jijón (Commission for the Protection of Human Rights, Ecuador)

- Wim Dierckxsens (International Observatory of the Crisis, Holland/Costa Rica)

- Vijay Prashad (Executive Director, Tricontinental)

- John Bellamy Foster (University of Oregon, USA; Monthly Review)

- More on Samir Amin

A man lives so many different lengths of time

Lau Kin Chi [top]

For Samir Amin’s anniversary on Sept 4, Global University for Sustainability invited Samir’s friends to reminisce their interactions with Samir and celebrate the very rich life that Samir lived.

Samir and I met on March 1, 2002. It was the first day of the World Forum of Networks of Civil Society, named Ubuntu, in Barcelona. About 100 people from 50 organizations from all continents were represented in this forum. Over breakfast, Samir and I happened to sit opposite each other at a small table. Samir asked me where I was from. I said, Hong Kong. His eyes glistened, and he enthusiastically told me, you must link up with one excellent group in Hong Kong, with some of the best activist intellectuals from all over Asia doing a lot of good intellectual work. I listened in earnest. The name of the group is ARENA, Asian Regional Exchange for New Alternatives, he said. I told him, I am Co-Chair of ARENA. He burst out laughing, and that instant sealed our friendship in the years to come. Samir knew many senior fellows of ARENA, hence we shared fond friendships with Muto Ichiyo, Mushakoji Kinhide, Surichai Wun’gaeo, Samuel Lee, Vinod Raina, and many others.

During the two days of the Ubuntu forum, Samir and I sat together all the time, sharing news, analysis, and ideas for future projects. The next year, he recommended Francois Houtart to attend, as observer, the ARENA Congress held in Kuala Lumpur. Since then, Samir, Francois and I had worked closely together to organize panels in all World Social Forums and other projects such as the Caracas Gathering in 2008, Samir being the President of the World Forum for Alternatives, Francois being the General Secretary, and I being one of the Vice-Presidents. In 2010, we started preparations for the Global University for Sustainability, and we have been organizing the South South Forum on Sustainability (SSFS) since 2011. The Global University for Sustainability was officially launched at the Tunis World Social Forum in 2015. (See “Comments of Samir Amin and Francois Houtart on the Founding of Global University for Sustainability.”)

There are so many stories to tell about Samir, he was always offering wise and incisive analysis of the world’s crises, and at the same time assessing the challenges and proposing visions and strategies for movements. His optimism was contagious, he would always point to possibilities for action and hope.

Samir, with his charisma, had friends of all ages and from all continents. As we had worked closely together in the World Forum for Alternatives, we had met almost every year. Now and again, he would crack a joke, either himself feeling like telling one, or on my request: Samir, a joke please! It might not be the first time I heard the joke, but I would enjoy it like anew. Samir would start in a serious tone, as if he were to give a lecture; he would tell the joke with such affection that he would himself be most amused and laughing heartily before his listeners joined in the jesting. With integrity and dedication, with passion for life, with optimism, Samir was most uncompromising with bureaucracy, cronyism, opportunism, mediocrity, and dependency.

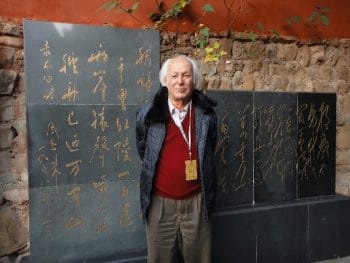

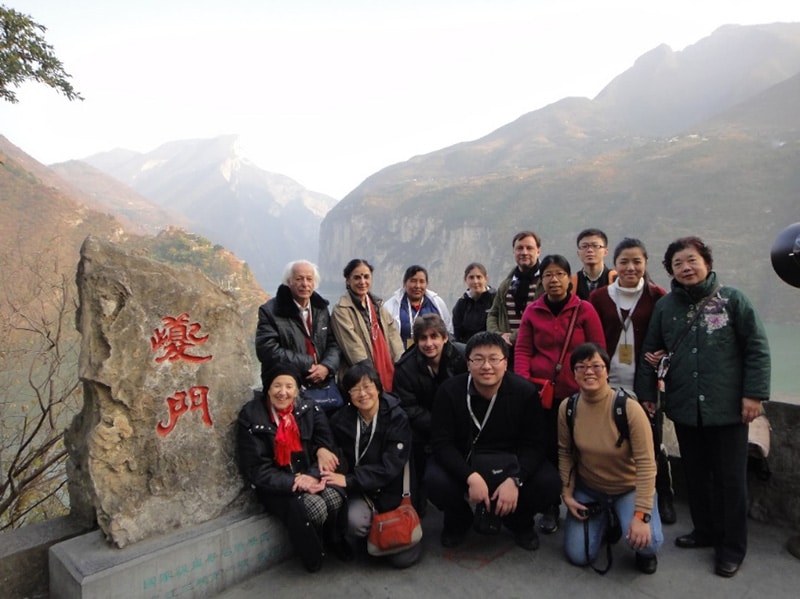

Samir had nurtured a deep friendship with comrades from China, including Wen Tiejun, Wang Hui, Dai Jinhua and Huang Ping. In December 2012, he and Isabelle attended the Second South South Forum on Sustainability in Chongqing, China. Before the Forum, we took a cruise along the Yangtze River, debating on the Three Gorges Dam and China’s development, and we had a lot of discussions about where China stood, four years after the 2008 global financial crisis. Two months later, he published a paper “China 2013” in Monthly Review (Samir Amin, “China 2013,” Monthly Review 64, no. 10, March 2013), which gave a comprehensive and concise elaboration of his analysis of the features of Chinese society from 1949 to 2013. While he was known to be an admirer of the Chinese revolution and the trajectories of delinking that China had taken, Samir was concerned with scrutinizing the contradictions and constraints. He would examine the complexities in the clash of forces between the left and the right, at the levels of the state, the intellectuals, and the labouring people. He would examine the complexities in China: use of distributed agricultural land is given to rural families but not privatized; China’s “socialism with the market” enables partial and controlled capitalist globalization; China as an emerging power is “precisely because it has not chosen the capitalist path of development pure and simple”, and “the system makes possible the retention of the majority of the surplus value produced there”, and so on.

We had a prolonged discussion about these issues during Samir’s trip to Beijing in May 2018. We discussed two key questions in China: peasants’ right to land, and financial globalization. We also assessed the status of China in the international politics of increasing containment. China has certainly been squeezed with the 2012 Obama administration’s “Pivot to East Asia” regional strategy, as well as the 2013 consolidated alignment of six core currencies (USD, Euro, GBP, JPY, CAD, CHF) in a long-term currency swap agreement. Faced with increasing targeting of China as the main threat to the hegemony of the core countries, the Chinese leadership, a complex body of relations of forces, could be vacillating between on the one hand, more concessions and further integration into global capitalism if allowed, and on the other hand, a shift of its domestic and international policies toward the rallying and consolidating of support and solidarity from the masses within China and the countries at the periphery and semi-periphery. Samir reiterated that China’s trajectory since 1949 had been one of the best examples of delinking, along with Vietnam and Cuba. He believed China should keep the gains for the peasants from the agrarian reform, small peasantry farming should be encouraged to ensure food sovereignty, democracy had to go with social progress, financial globalization must be avoided, and China should renew its internationalist partnership and solidarity with the global south, in the Bandung spirit, to counter the oligarchic triad of USA, Europe and Japan.

Samir reiterated his concept of the strategy of delinking – setting a country’s development agenda according to one’s interests and needs for industrialization, economic and social progress, and people’s welfare, resisting the imposition of the logic of capital and capitalism, and fostering an alliance of anti-imperialist forces because the Triad is the primary enemy of all peoples. Delinking is not a complete closure of the country from the outside world; it is a refusal to be subject to the coercive demands of global capitalism and global division of labour by the Triad. As Samir said, “‘Delinking’ is not at all a synonym for autarky. We mean the organization of a system of criteria for the rationality of economic choices based on a law of value, which has a national foundation and a popular content…” (Samir Amin, “A Note on the Concept of De-linking,” Review, 1987, X, 3, Winter, 435-444). Note that Samir had always stressed the “popular” content.

In this last trip to China, Samir knew, but did not tell us, about his fatal illness. He was as energetic in his expositions, and as loving of the Peking duck which was his favourite dish. The only difference was, unlike in the past, he refused to let us buy small gifts of porcelain, calligraphy or tea for him and Isabelle. He only wanted to take a walk in his favourite alleys.

On August 6, 2018, I received a message informing me that Samir was hospitalized in Paris. On August 8, four days before his death, Remy Herrera and I paid a visit to Samir in Broca Hospital. Samir talked again about the necessity for a global network for “transnationalization”, and when asked to define it in relation to the word “internationalism”, Samir said, “transnationalization” is internationalism, only a different word for the same meaning. He said it would be a long way to go, but the groundwork need to be done, and vibrant social movements should be the protagonists, while political parties and governments could be involved to give support to the people’s alliances. We talked about his love for China and the need for China to strengthen its strategic cooperative partnership with Zimbabwe and other African countries. When I was to take leave, Samir came down from his bed. Barefoot, he walked me to the corridor. I had planned to see him again in two weeks, but the hug turned out to be the final farewell.

The shock and grief over Samir’s departure is indescribable. To come to terms with this separation, I would read a poem that Anita Rampal sent to me a year after Vinod Raina departed in September 2013. Vinod and Anita were with Samir and Isabelle in the 2012 cruise trip on the Yangtze River. There was so much laughter, so much fun, so much argument, so much passion…

Samir, the audacious thinker and militant, lives. On this anniversary, let us celebrate his living legacy.

So how long does a man live, finally?

By Brian Patten

So how long does a man live, finally?

and how much does he live while he lives?

We fret, and ask so many questions-

Then it comes to us

The answer is so simple.A man lives for as long as we carry him inside us,

For as long as we carry the harvest of his dreams,

For as long as we ourselves live,

Holding memories in common, a man lives.His wife will carry his man’s scent, his touch,

His children will carry the weight of his love,

One friend will carry his arguments,

Another will hum his favourite tunes,

Another will share his terrors.And the days will pass with baffled faces,

Then the weeks, then the months,

Then there will be a day when no question is asked

and the knots of grief will loosen in the stomach

And the puffed faces will calm.And on that day he will not have ceased,

But will have ceased to be separated by death.

How long does a man live, finally?A man lives so many different lengths of time.

Wang Hui, Tsinghua University, China [top]

It was in 1995 that I first met Professor Amin, in Copenhagen. I was a visiting researcher in the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. Professor Amin was in Copenhagen to attend and speak at the NGO forum of the United Nations World Summit on Social Development. The Nordic Institute invited Professor Amin to give a speech.

The reason for this invitation was that Asia, in particular the East Asian region, has entered the so-called globalization process. Japan, the four small dragons of Asia, as well as China with the reform, had started on a new wave of economic surge. On that basis some scholars believed that the kind of thoughts around ‘de-linking’ put forward by Amin were perhaps outdated. Professor Amin made his speech in face of this theoretical challenge.

During the speech, Amin pointed out that the new wave of globalization process was formed over the course of long history. It had not changed the five major monopolies that were formed during the imperialism era—natural resources, science and technology, mass media, finance, and weapons of mass destruction. Under the condition that these five monopolies had not been fundamentally changed, the globalization process would definitely lead to a new round of global disorder.

That year, basing on Amin’s speech, making use of it as research reference, I wrote a paper while in Copenhagen entitled “Order or Disorder—Amin and his views on Globalization”. It was published in the journal “Dushu [Reading]” later that year.

During the 1990s, the Chinese intellectual realm generally held a sense of optimism on globalization, somewhat wishfully. The analysis of Amin on the potential risks of that process was indeed rare and most valuable.

Since then, together with many friends, particularly Lau Kin Chi, Wen Tiejun, Huang Ping and Dai Jinhua, I have participated in social activities and academic discussions organized by Professor Amin. We have also invited him to Tsinghua University multiple times to make speeches, hold seminars and conduct discussions. Professor Amin was an outstanding representative of Third World intellectuals. His many astute opinions are of particular value today.

Among his views on globalization, the most important one is that: the structure of the five monopolies has made it impossible for the new globalization process to generate a new order that would suit the Asian region, nor could it provide new roles and new conditions for the development of African countries; on the contrary, once the rise of China, Asia and other regions upsets or affects the constitution of the five monopolies, the old imperialists would pounce back. That is the most dangerous situation faced by the world today, and the root of the global disorder.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Wen Tiejun, Renmin University of China, China [top]

I came to know Professor Amin at the World Social Forum. From the moment I knew him I had been overwhelmed by the wisdom, tolerance and profound thinking of his generation of veteran revolutionaries. Later, I also attended the World Forum for Alternatives which he hosted. It was not a very large organization, consisted mostly of third world thinkers, theorists and intellectuals, highly cogitative in nature. Whether it was him coming to China or me going to the World Social Forum, we would have lengthy discussions every time. I strongly agreed with him on his astute views regarding the laws that evolved from the globalization of financial capital, and also agreed with his analysis on China’s response to the challenge of globalization. We became cross-generation friends.

In my recollection, every dialogue I had with Professor Amin was a hearty and lively exchange. The logic of his discourse was very clear, supported by copious citing, yet never deviating from the main theme: although what was involved—the negative situations of developing countries—had been complicated and manifold, yet it was mostly due to the objective laws around capitalism’s global development. Regardless of how core countries attempt to transfer out the costs of crises through virtually expanding the financial capital, the trend towards the final outcome of a collapse is irreversible and inevitable.

In these words to commemorate Professor Amin, I would also like to make a special note that in China, the main person following the steps of Professor Amin’s thoughts and activities is Professor Lau Kin Chi from Lingnan University, Hong Kong. From my first meeting with Professor Amin to the last, it had been Professor Lau who made the arrangements and mediated between us. My English was not too good and I had relied on her every time to explain unfamiliar terms and concepts to me. She would always modestly serve to take pictures and recordings of every discussion. These materials have become even more precious now that Professor Amin is no longer with us. I look forward to seeing Professor Lau’s writing of “Samir Amin in China”.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Huang Ping, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China [top]

I first started reading Amin’s writings in the mid-1980s and was deeply impressed by the delinking theories he proposed. That was because before then I had a rather low level of understanding on the position of Asian, African and Latin American countries in the world economic structure and system after their de-colonization and independence. As soon as I read the writings of Amin, I felt its overwhelming power. I met him in person in Paris in the mid-1990s. At the time I was participating in voluntary work for one of the intergovernmental councils of the UNESCO. Amin was quite elderly by then yet every year when I went to Paris he had come to the airport to pick me up. Every time we would first discuss about Europe, then Africa, and of course China. Listening to his critical analysis on global capitalism, I found that his understanding on contemporary capitalism had become much more profound than when he proposed the de-linking theory in his early stage. During this time I also came to know some of the people he was well-acquainted with: Gunder Frank, Immanuel Wallerstein, Giovanni Arrighi and so on, and have invited each of them to attend relevant academic conferences in China. One very deep impression was from one summer early in this century: together we organized a three-week summer school in Spain for Spanish civil service personnel and young scholars. Amin and the aforementioned scholars (Frank had passed away by then) would express their astute opinions on the relationship between developing countries in Africa and so on and the developed countries, highly inspiring to the audience.

The final two encounters that left me with deep impressions, one time was in Paris. Arrighi had passed away. I went to Amin’s home, and Arrighi’s wife Beverly Silver was also there. While remembering Arrighi, we also talked about China, Europe, Africa and the possible developments of USA. We went on until dawn. Another time was during his last visit to Beijing to attend a forum. I was not able to attend but had met him in the evening. We again talked about the direction the world would proceed next. He proposed two key points regarding China which were later published. One was regarding the nature of land, and the other was the position of state-owned-enterprises.

The deepest impression Amin gave me was that of a persistent thinker on world development, who continuously critiqued the issues and contradictions during development. Another was that he had all along cherished hope and confidence in China’s development.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Dai Jinhua, Peking University, China [top]

In a World Social Forum early this century, in the company of Kin Chi, I met in person Samir Amin, the third world thinker whom I have known for a long time through his writings.

After that, I, and we, have followed his footsteps, in one after another World Social Forum and third world forums, in social movements in Africa and Latin America, in our South-South Forums, and met with him time and again. When we first met, he was unlike any other top-notch international thinkers, but rather, more like an activist, a leader and organizer of anti-globalization movement. At almost eighty, he still went around like a whirlwind, always organizing, arranging, speaking and conversing. At the same time, there were his new writings, in French, English and Arabic, published one after another. Gradually entering his acquaintance, knowing him almost as well as one of the family, I recognized the sense of urgency that he carried, at times burning, that had originated from 20th century revolutionaries: regarding to the new Internationale, regarding an alternative form of international cooperation, regarding the third world’s way out and that possibility, about Asian-African then Asia-African-Latin American alliance… To him, age had only exacerbated this sense of urgency. He seemed to be fighting all-out for time with the unknown, to arrange, to deliver, to conceive, to think about the future of the third world and the future of the world, to continue in the struggle against the hegemonic structure of the world.

World Social Forum, Tunis, March 28, 2013. From left to right: Wen Tiejun, Francois Houtart, Samir Amin, Lau Kin Chi, Dai Jinhua, Chen Xin.

Wise and free-reining, sincere yet pressing, he did not bother to hide his impatience and distain with some internationally renowned academics, yet for those he called his “comrades and fighting-mates” he would have boundless tolerance and patience. I have seen him, time and again, calmly and patiently listening at length to the rather vacant clichés of young people in social movements, seen him answering the young people seriously, including some elementary, basic questions raised by my own students.

To me, perhaps another genuine and deep recognition was his profound love and emotion towards China. Having followed Amin over a long time, I would from time to time be asked by friends in the western academic circle regarding Amin’s situation. Opening or covertly, their attention had involved the complex, intricate realization and emotion arising alongside China’s rise. As such the question had frequently been: Is Amin still unconditionally identifying with China? My answer would be clear cut: Yes. When this type of questions, or more appropriately, challenges, kept on being repeated, I finally sought Amin’s confirmation once again. His reply was clear and definite: it was because China is the one and only example of economic and political practice that had reversed the historical karma of a third world country through independence, self-determination and self-reliance. The success of China is the third world countries’ encouragement and hope. Yet I know at the same time that his deep love for China was not out of innocence. He had penetrating observations and theories as well as practical reflections on China’s issues. His alertness and worries over the international context that China is and will be encountering are not found among the majority of Chinese scholars. In his final years, he once again talked to us, with the hope that we would understand the threats of transnational financial capital and American hegemony with a clear mind.

In May 2018, he came to Peking University to attend an academic conference. We gathered with him, Kin Chi and the students, like old friends and family. He jokingly displayed the cover of Peking University’s appointment of him as an honorary professor, the insert of which had not yet been put inside. He was happy that our students had read and were familiar with his writings. At that time, we did not know, and could hardly imagine, that this was an old man suffering from brain cancer. We could hardly imagine that merely three months later we would be forever parted with him.

In August, in London, on the other side of the English Channel, I learnt about his departure. At that moment, it seemed as if one part of the sky had suddenly dimmed, one corner of the world had closed the curtain. I dropped on to the chair and cried. At the same time I knew very well that although as an activist he had ended his activities, yet as a thinker his heritage will remain on fire and glow.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Lu Aiguo, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China [top]

The last time I saw Samir Amin was on 4 May 2018. He was in Beijing preparing to attend the Second World Congress on Marxism. That afternoon, Amin and his two African colleagues came to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences to have a discussion with some of the people there. I was one of the participants and had the great opportunity to meet and speak with Amin. It was not a big seminar and as such it gave me the opportunity to repeatedly raise questions on social development, and to listen to Amin’s detailed analysis and interpretations. As before, in conversing with Amin face to face, in addition to appreciating his academic accomplishments and theoretical rigour, very often I would also be deeply touched by his staunch communist convictions and charisma in treating others equally and amicably.

Out of this feeling, I couldn’t help but seek opportunities to talk to him whenever possible. He was always welcoming. I remember once going to Algiers for a seminar several years ago. At mealtimes, whenever there was a seat next to Amin, I would aggressively seize it in order to talk to him over the meal, even though it meant robbing others of that opportunity. He would always respond to my questions carefully and candidly. I have benefited greatly from every such occasion.

At the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences seminar, Amin was wearing a dark blue Maoist style suit, and my eyes brightened. It was not the only time that he was dressed that way. I have seen it several times in China as well as in other countries. One time was around ten years ago in an international seminar at Madrid. He was wearing this kind of outfit when delivering his speech. During the coffee break I half-jokingly asked him why he would be wearing such a suit, while in China it had long since been considered ‘outdated’ and regarded as a sign of being old-fashioned or not emancipated ideologically. He smiled and replied that he liked the suit, and it was comfortable to wear. The way I see it, this gesture showed his heartfelt appreciation of not only new China, but also of China’s revolutionary tradition. That was the impression I gathered from my many conversations with him. I had discussed with him some of my concerns regarding changes in Chinese society since the Reform. He expressed understanding yet he still placed high hopes on China, with the view that China’s success in development has paramount significance to the future of the third world as well as to the changes in the world system. At the same time, he also repeatedly stressed that land should not be privatized in China. He considered it as a crucial determinant of the future direction of the Chinese development.

It was entirely unexpected that just three months after the meeting in China, Amin left us. In that meeting, his revolutionary spirit and scholarly disposition had been the same as ever. I did not have the least inkling of anything unusual.

He had founded the World System theory together with Wallerstein, Arrighi and Frank, providing a powerful theoretical weapon in understanding the past, present and future of capitalism. He was an outstanding Marxist all along. As he himself put it, “I consider Marxism a weapon for battle rather than a theory. Using that famous saying of Marx, not only should we know the world, we should moreover change the world.” As a true people’s intellectual, Amin had, throughout his life, devoted himself to the practice of struggle, contributing his life vigor to the liberation endeavor. He will always remain a role model that will encourage us to move forward in solidarity in pursuit of a better world.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Sit Tsui, Southwest University, China [top]

In 2011, I followed my teacher Lau Kin Chi to join the Subversive Film Festival held in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. It was my first time to meet Prof Amin. The host invited several renowned leftist intellectuals like Antonio Negri, Slavoj Žižek, David Harvey, and Gayatri Spivak. On the stage, Prof Amin argued heatedly with some of them. I was impressed by the sharpness of the revolutionary thinker. Off the stage, Prof Amin acted as a tourist guide, taking Kin Chi and her group to visit historical sites in Zagreb. It was my first time feeling the amiableness of the revolutionary organizer.

In 2012, Southwest University, Lingnan University, and Renmin University of China co-organized the Second South-South Forum: Sustainability and Rural Reconstruction. We were very honored to invite Prof Amin as the keynote speaker. We organized a pre-Forum tour for overseas guest speakers to visit the Qin Ranges, Three Gorges, among others. The aim was to introduce them to the cultures and customs in southwest China. Along the way, we basically did three things: traveling, doing research, and having debates. As the cruise gradually moved on, we appreciated the beauty of the banks of Yangtze River. When we passed the Three Gorges Dam, the whole group had a heated debate: what does sustainable development mean? What does China’s path mean? When we arrived in Shanxi province, I was responsible for facilitating the visit to Puhan Rural Community in Yongji City, in order to learn how local peasants were self-organizing, promoting cultural activities, and working on ecological agriculture. All these made Puhan one of the best models of rural reconstruction. Prof Amin listened carefully to local peasants’ speeches. He sometimes raised questions, and sometimes nodded with a praise, particularly when he saw their own products: grains, vegetables, fruits, and handicraft. At the Forum, Prof Amin delivered a keynote speech, entitled “The Implosion of the Contemporary Capitalism”. He criticized the developed countries for countlessly producing crises, and explained how Egypt suffered. At last, he emphasized that people of the developing countries should be self-reliant but also cooperate with each other.

In 2013, the World Social Forum was held in Tunis, in which we organized a panel on China. Prof Amin and Prof Houtart supported with their presence. In 2015, the World Social Forum was again held in Tunis, in which Kin Chi announced the inauguration of the Global University for Sustainability. Prof Amin and Prof Houtart were founding members who enthusiastically promoted it among their friends from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

On 5-9 May 2018, Prof Amin came to Beijing to attend the Second World Congress on Marxism. Kin Chi and I brought a video camera to interview him. He gave his warnings: “Defend the fruits of the Land Revolution. Do not join financial globalization!” During those days, he always wore a blue Maoist jacket. He said he had kept it for decades, and got it mended many times, as he emphasized that whenever he arrived in China, he wore it. Afterwards, Kin Chi, Wang Ping and I accompanied him to visit Liulichang Cultural Street, where there were Chinese ancient books, paintings, handicrafts, artistry, antiques, calligraphy, and the scholar’s four jewels (writing brush, ink stick, ink slab and paper). We had afternoon tea with a pleasant chat. In the evening, we took a taxi to go back to the hotel. When the taxi passed the Houhai, Palace, and Tiananmen Square, I noticed that his eyes were full of nostalgia.

On 1 September 2018, at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, Kin Chi and I attended the funeral of Prof Amin. (See “In Memory of Samir Amin (1931-2018)”)

The funeral of Samir Amin, September 1, 2018. Red roses covered his grave, dedicated to The Internationalist Militant.

Wang Ping, China Society of Economic Reform Journal, China [top]

During the summer holidays in 2018, Professor Lau Kin Chi contacted me saying that she was attending a conference in Beijing, and that perhaps we could meet. She then said that Prof Samir Amin was also in Beijing attending the conference and would like to make a tour of Beijing afterwards. She asked whether I would like to go with them. I was of course more than happy to do so.

That day, Prof Amin had kept on looking for the old places that were in his memory. We first sought out Liulichang Street. Strolling along the walking street with its pervasive antique, classical flavor, Prof Amin and Kin Chi conversed continuously, at times bursting out in laughter. They were reminiscing on the funny things that they had shared in the past. I took snapshots of them while chatting with Sit Tsui.

Later, on the way back to Peking University, the car went past the corner tower in Jingshan Front Street north of the Imperial Palace. Prof Amin told us that was where he had stayed back in 1978 when he was invited by Deng Xiaoping to visit China. At that moment, with the evening sun shining on the corner tower’s overhanging eaves, it had appeared weathered yet resplendent.

The news of Prof Amin’s departure came not long afterwards. I selected one of his papers for print in the publication that I worked for, one that talked about the necessary caution over internationalization of the Renminbi. His viewpoints and cautiousness had come from a perspective formed over half a century, reflecting his sincere and earnest wishes.

In the summer of 2019 during the Sixth South South Forum at Lingnan University in Hong Kong, one evening session was dedicated to the commemoration of Prof Amin. Amidst the elegiac music, Prof Amin’s life gently unfolded like a scroll of painting, determined, unflinching, tumultuously surging forward to its end. And I only had the opportunity to witness one glimpse of his life. To me, he was like a shooting star that streaked across the night sky of my life. That leisurely summer day, although it was the final time for Prof Amin, his laughter will forever glisten in the recess of my remembrance, like a silent film with vivid colors.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Yan Xiaohui, Global University for Sustainability [top]

Prof Samir Amin was a good friend of my doctoral supervisor Professor Lau Kin Chi. I have come into contact with his writings and thoughts at an early time. In 2011 during the First South South Forum, I heard many speakers quoting from his theories regarding the “implosion” of capitalism.

The following year in the Second South South Forum, my supervisor and I organized pre-forum field trips in China, and as such we had spent one whole week’s time with Prof Amin from morning till night. Not only did I have the opportunity to ask him about serious topics, I was also able to hear him tell funny stories and admire the political caricatures drawn by his wife Isabelle. Obviously, I also had the opportunity to be his guide, introducing to him China’s rural conditions.

What I found most impressive with Prof Amin was his easy-going ways and his humor in treating young people. He would seriously answer my questions every time, and then half-jokingly ask me a small question. He likes China very much and would pay attention to all kinds of things about China, carefully raising very detailed questions.

Since then, I have accompanied my supervisor in several interviews with Prof Amin, which were released through the Global University website. His theory on ‘de-linking’ has also been important reference material for my doctoral dissertation. Later, when working on topics with regard to China’s experience, our project team would often make references to his theories. Professor Wen Tiejun highly appreciated Prof Amin’s thinking, and directed us to make use of it in analyzing issues around present-day globalization.

After the departure of Prof Amin, I participated in the workshop organized by Tsinghua University in his commemoration. I believe the heritage that he has left to young people, which is well-worth our learning from and taking on, other than his immense number of theoretical writings, is more importantly his perseverance in standing with the colonized peoples and countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, never faltering in his support to the resistance of the oppressed against the existing rule of capitalism.

Translated from Chinese by Alice Chan.

Muto Ichiyo, People’s Plan Study Group, Japan [top]

It was in the early 1970s that we met with and became excited by dependency theories. Marxist intellectual influence was quite strong in this country, particularly in academia, but its vista was narrowly limited to analysis of Japanese capitalism and Leninist understanding of imperialism. True, Prof. Uno Kozo had developed a unique, brilliant structuralist reading of the Capital but that did not help much in the grasp of the division of the world into the commanding and shaping core and the commanded and shaped peripheries. And it was the period of history ushered in by the indomitable Vietnamese people’s struggle against the super-imperialist power’s mass military intervention. The Third World had made its presence felt in the core capitalist metropolis, of which Japan had become a part.

In1970, I met with Ms. Kitazawa Yoko, a revolutionary feminist and economist back from Cairo, and concurred on the need to tap the rising theoretical resource of dependence theories and related practice. We, with another like-minded friend, launched a book series titled Rentai-sen (Solidarity). We devoted its 4th volume to dependency theories and theorists, myself writing about Gunder Frank. While we did not introduce Samir Amin in that issue, we followed by getting our friend Hanasaki Kohei to translate Amin’s Accumulation on a Global Scale.

I guess this was the first full translation of Amin’s work in Japan, certainly helping to arouse interest in dependency theories and approach.

I think in that process I got in touch with Samir by exchange of letters. Frank may have put me in touch with him, but I am not very sure. Anyway, I think Samir must have known about us as we had started an English quarterly publication, AMPO, in 1969, which was circulated through then proliferating movement channels across continents. On the basis ofAMPO, we established the Pacific-Asia Resource Center (PARC) in 1973.

I think it was in the second half of the 1970s that I met Samir first when he visited PARC office. I cannot identify which year it was, but it was toward the end of the year as I remember. After his talk we had a big year-end party and he and his wife, Isabelle, joined, chatted, and drank much. That I think was the first time I met him.

We felt his talk at PARC was brilliant, clear and precise. Besides, he carried with him no professor air. Our staff were fascinated by his sinewy delivery. He was a militant activist, thoughtful and precise, being of course a scholar equipped with power of logic. That impressed us.

In 1989, PARC took the initiative in organizing a major international program, People’s Plan 21, in search of people’s processes to build an alternative world. On three occasions, in 1989, 1992, and 1996, we had multi-sector, multi-issue programs with large convergence assemblies in Minamata, Bangkok, and Kathmandu.

I am not sure exactly which year, but probably in 1990 or so, I had a phone call from Samir in Paris. He said he decided to establish a World Forum for Alternatives and wanted me and PARC to join as one of the initiators. I gave some serious thought to it, exchanged views with him over the phone a few times, but failed to agree to join. The reason was that Samir’s project sounded like building a new version of party international on the basis of a political program adopted by its adherents. The PP21 concept originated in the critical reflection of the 20th century party-led, state-oriented revolutionary practice. We do need a political program, but that should be thrashed out and renewed in dynamic processes of people with differing interests and cultures interacting with one another. My emphasis is on the processes and the role of mediating agencies.

I met Samir last in 2002 at the World Social Forum in Mumbai, but then we were too busy to sit together to talk. As Lau Kin Chi was working closely with him, I was kept informed of his activities and appreciated them. His contribution was immense. I respect and thank him for opening our eyes to the mechanism that perpetuate inequalities through history, which is still there to be abolished.

True, Khmer Rouge theoretically led by Delinking Theory’s loyal student Khieu Samphan caused horrendous havoc on the Kampuchean people, society, and culture as well as the communist-socialist movement. True, delink a revolutionary society from the capitalist world system and take steps toward autarchy was Amin’s strategic orientation. But can we blame the Kampuchea tragedy simply on this thesis? I don’t think so. In bringing about meaningful social change, we always need certain delinking from the dominant practice and system. I think the Amin’s thesis and the Khmer Rouge practice should be “delinked,” reexamined separately, and then put to scrutiny of the nature of their inter-relatedness. If this study has been already made in movement history academia, I apologize for my oversight.

I miss Samir Amin as my historical compatriot in another sense—I was born in the same year (1931) and in the same month (September) as was Samir. We were biting the same huge apple in the same historical time.

Alexander Buzgalin, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia [top]

About Samir Amin—one of the greatest theorists and an outstanding public and political figure of the left spectrum of the 20th century, a real communist and fighter for the socialist future of mankind.

Samir Amin and I have been friends and associates for many years. I will begin with a story about my last face-to-face meeting with Samir Amin, because everything that was characteristic of our long-term communication was manifested in it.

Samir Amin was a great friend of Russia, he truly loved Russia and the Soviet Union. Many of his books have been translated into Russian, including those devoted to the fate of Russia. For him, the main event in history was undoubtedly the October Revolution, and the departure of the USSR from the historical arena was the greatest tragedy of our time.

Our last face-to-face meeting took place in Moscow in October 2017 at an International Forum dedicated to the anniversary of the October Revolution of 1917 and the future of socialism. It was a symbolic and important meeting not only for me, but also for all those who witnessed the reports and speeches of Samir Amin.

At this forum, Samir Amin not only made reports, but also participated in the “Theater of Living Ideas”, where famous scientists took responsibility for presenting the position of one or another creator of the revolution, and further on their behalf argued what happened then, in 1917, about how to evaluate what happened a hundred years later.

Samir Amin in this play—which was also a scientific dialogue—took on the role of Stalin. Samir Amin, of course, was not a Stalinist, but he took on the mission to present the position of this figure, for he always saw the world as a whole, in contradictions, in the real dialectic of life, which is always simultaneously tragedy, regression, crime, and an optimistic drive of the future. This is how Amin presented Stalin: as a person who simultaneously strives for socialism and commits crimes, as a symbol of victory in the Great Patriotic War (a victory that echoed the movement of the masses towards socialism throughout the world, including Africa, which was witnessed by young Amin himself), and the common name of the bureaucratic dictatorship.

Amin saw the whole world in the same dialectical way, in the integrity of contradictions. For him, capitalism has always been a world system—a single whole. In this whole, but riven by contradictions world, he always saw not only the situation in Europe or the United States, or other actors of the “center”, but also the entire huge “periphery”. He saw and analyzed the subordination and exploitation of this “periphery” by the capital of the “center”. He strove to embrace with his research the resistance movements in the countries of Asia, Africa, Latin America, each time showing that these links in the world struggle against global capital are again contradictory.

Samir Amin combined scientific rigor in presenting his ideas with personal charm, a sense of humor, he everywhere managed to attract the sympathy of the audience, initiate interesting and stimulated discussions.

Samir Amin, being a man of the world, at the same time was always first of all a patriot of his Motherland, worried and ached with his soul for all the problems of the Arab world. At the same time, he was a real European intellectual (with a touch of French aristocracy), immersed in the cultural problems of Europe, in many of whose languages he was fluent.

One of the hallmarks of Samir Amin, one of the greatest leftist theoreticians of the twentieth century, was the courage to pursue his theoretical reflections. He was not afraid to tie his conclusions to the realities of the struggle of specific social movements, parties, organizations. Samir Amin has always been included in the life and struggle of the left and social movements not only in his native Arab world, but also in other spaces—Latin America, Russia, France, the USA, China. Moreover, he himself initiated and organized the socio-political struggle. Examples of this are the Third World Forum and the World Forum for Alternatives, which Amin initiated and supported throughout his life.

This involvement in the life and struggle of left-wing social movements was the core of his whole life—the life of a scientist, politician, social activist. A cheerful, easy (with a hell of a busy life and activity), friendly person who always met you with the words “Hello, comrade” (in our communication he used to say it in Russian—“Zdravstvuy, tovarishch!”).

Samir Amin’s talent, energy, enthusiasm and willingness to start new projects that at first seem fantastic, but gradually turn into real ones—these are all distinctive qualities. Even at the end of his life, at eighty with a tail, he was not old; he always remained young.

I will briefly say what I think is especially important in the theoretical legacy of Samir Amin and his comrades. First of all, this is the conjugation of the historical-temporal model of considering reality that prevailed (and partly continues to dominate) in Marxism with the world-system approach, which puts socio-spatial interactions and the problem of the relationship between the “center” and “periphery” at the forefront. Samir Amin significantly advanced Marxist theory, having managed to combine Marxism and world-systems analysis, of which he was one of the founders.

In his works, Samir Amin managed to show how the historical and temporal pattern of deployment, change of social systems, their progressive and regressive transformations on the one hand, and their location, interaction in the social space on the other hand, are connected. The result is a picture that I would define as a historical map of social space or social space in its historical dimension. Thus, for example, a part of the world’s citizens (the smaller part!) enjoy the benefits of a social state, while the other part (the larger part!) lives under the conditions of largely barbaric capitalism, which is associated with the semi-feudal subjugation of man. And this is no longer just a division of the world into the center and the periphery. It is the conjugation of social space with the historical and spatial existence of societies in today’s world. And most of Samir Amin’s works reflect this conjugation one way or another.

Samir Amin made a significant contribution to disseminating among his colleagues an approach that recognizes that the socio-economic system of a particular country should be considered as part of a global system, without which it cannot be understood.

Samir Amin’s methodological and theoretical position made it possible to introduce into scientific discourse a whole range of theoretical developments, including such as the problem of imperialist rent, catching up development, overcoming the dependence of the periphery countries on global capital (delinking), etc.

I would especially like to note that in the works of Samir Amin all the main conclusions were proved, and they were proved mainly based on Marxist methodology and theory, supplemented by the world-system approach. This is exactly how—on the basis of identifying specific mechanisms of action of the law of value in the world space—he revealed the nature of imperialist rent. This is how he argued that breaking the dependence (and not only economic, but also political, ideological and even cultural) of the countries of the “periphery” on the capital of the countries of the “center” is possible only within the framework of a more or less radically realized, but necessarily socialist-oriented trajectory of development, as part of a course focused on the implementation and use of at least significant elements of socialist relations.

In particular, within the framework of delinking it was substantiated the necessity of such components of social and economic policy as state regulation and planning, significant public sector, especially in education, health care, culture, infrastructure, etc., redistribution of part of the profit in favor of workers through the progressive income tax and other channels, expansion of the scale of grass-roots and direct democracy, public support of genuine national culture, etc. The purpose of this social and economic policy is to promote social, socialist-oriented progress, to limit, reform and, in the long run, revolutionary transform capitalist relations.

For Samir Amin, both when he posed theoretical problems and in his social activities, the world has always been holistic in both spatial and temporal terms. He saw it in the counterpoints of subsistence economy, caste, poverty on the one hand; and digital technology, financial empires on the other hand; and the great revolutions and reforms that took place throughout the twentieth century around the world—on the third.

In conclusion, I would like to say that a real scientist is alive as long as he is treated as a real subject of scientific dialogue. Samir Amin stays with us while we read and propagandize his works, constructively criticize them, and develop the research traditions laid down by him.

Sami Amin, a major actor and thinker of decolonization

Gustave Massiah, Centre for Development Research and Information, France [top]

I met Samir Amin in 1965 in Dakar. He was a professor at the University of Dakar, I worked at the Ministry of Planning and Development. We were both born in Egypt and that was a starting point for us. I had heard of him, of his book on Nasserian Egypt, published under the name Hassan Riad, of his work in Mali for the Plan and of his first publications on Africa. We soon became friends and began fifty years of common struggles and fraternal friendship. This friendship has never weakened. Even if we sometimes did not completely agree and even disagreed, trust and friendship always prevailed.

During these fifty years, there has been no shortage of adventures together. I will only recall a few of them. From 1970 to 1980, Samir Amin was director of IDEP (United Nations Institute for Development Planning) where he was a professor. He made IDEP an extraordinary centre for the creation of African thought and also a place of support for African intellectuals in danger as soon as they freely expressed their critical thinking. In 1975, Samir asked me to propose a reorganization of IDEP, of which he says in his Memoirs “I did not implement his recommendations because of the attacks of my opponents”.

Samir organized numerous seminars that were major forums for debate on global development thinking. I was fortunate enough to participate in several of them. As an extension of his book Accumulation on a World Scale, he invited the great authors of a renewed world history, notably Immanuel Wallerstein, André Gunder Franck, Giovanni Arrighi. His book, The Unequal Development, published in 1973, served as a basis for the launch of an alternative way of thinking about development.

In 1975, on Samir’s initiative, we published a joint book, The Crisis of Imperialism, at Editions de Minuit. With four contributions: that of Samir Amin, a structural crisis; that of Alexandre Faire, inter-imperialist conflicts in the crisis, that of Mahmoud Hussein on the active role of the periphery, the Arab example, and mine on the international division of labour and class alliances.

Samir Amin has never been afraid of going against the tide. In 1989, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Samir proposed to organize a seminar in Dakar in 1990 on the future of socialism. He asked me to write a provocative contribution on the future of socialism in Europe.

In 1997, we started out on new adventures. Samir considers that the Third World Forum should be complemented by a World Forum for Alternatives. He launched it with François Houtart and here we were involved in preparatory meetings in Brussels. The World Forum for Alternatives was launched in Cairo in 1997. In 1999, we organised with ATTAC (Association for the Taxation of Financial Transactions and Citizen’s Action) , which was created in Paris in December 1998, a counter-summit in Davos. From then on, we became involved in the adventure of the World Social Forums, and the first of them, in Porto Alegre in 2001.

Samir Amin was one of the major thinkers of decolonization, of this alliance between the struggles for social and cultural emancipation and national liberation. Decolonization is not over; its first phase is completed with the independence of States whose limits we can see; its second phase, that of the liberation of peoples, is based on individual and collective emancipation, and the construction of a common humanity.

Samir Amin was a thinker, in movement and involvement; a Marxist from the South. A point of view from the South, beyond the change of perspective, is an alternative point of view of the world: starting from the blind corner to clarify and make visible the whole.

Samir Amin has mixed in his work a ‘political economy of decolonization’ and a ‘critique of the political economy of globalisation’. Since the early 1960s, he has placed his work on development in the perspective of globalization, on the one hand, and in the debate on transition, on the other. His approach peripheral and dependent capitalism reaches its full depth when it is inscribed in the analysis of the global accumulation of capital and in the attempt to surpass capitalism.

This theoretical and strategic contribution of Samir Amin has given him a particular stature; it is not understandable if we cut him off from his political commitment. This commitment has been concretized at all levels. He was present in all the major world mobilizations and demonstrated that his indignation capacity, always intact, did not weaken the sharpness of his analyses and the relevance of his proposals. Its radical analyses always sought to highlight the roots of the problems posed. His proposals were powerful because they did not seek to make cosmetic changes, which were often illusory, but because they were part of a desire for long-term structural reforms and highlighted the importance of the ruptures and upheavals that were necessary if we really wanted to change the situation.

Samir Amin could have been an intellectual privileged by those in power; he had chosen not to be and preferred to obstinately denounce Eurocentrism. He could have been the reference and alibi of the state bourgeoisie; he had chosen not to be one and preferred to criticize without concessions the impasses of regimes built on the confiscated heritage of national liberation. His deep and vivacious Egyptian culture allowed him to combine his contained anger at injustice, the century-old patience of the peoples of the Nile and a devastating sense of humour. Samir Amin was an example of a vigorous and creative mind, a free and committed man.

Michael Hudson, Institute for the Study of Long-term Economic Trends, USA [top]

Despite the great similarity of our ideas, I didn’t meet Samir until Greece just prior to the Syriza disaster in 2015. We were both invited to the Delphi meeting urging rejection of the Eurozone terms.

Boris Kagarlitsky introduced us and told Samir that he was surprised that he hadn’t met me before. We talked briefly about the dynamics of U.S. imperialism.

The second time I met Samir was in Beijing at the Second World Marxist Conference at PKU. We talked about Marxism’s base in classical British political economy.

Patrick Bond, University of the Western Cape, South Africa [top]

Samir Amin’s celebrated life was amongst the most trying, but also rewarding, of his generation’s left intelligentsia. His political and professional fearlessness were two traits now recognised as exceedingly rare.

I last visited Amin in early 2018, at his old-fashioned Dakar home-office in a dilapidated bank building, which decades ago was one of West Africa’s greatest skypscrapers. He was busy with a stream of new essays and books, and although expressing far less confidence in statist counter-hegemonic prospects than in prior eras, he maintained faith that new waves of people’s movements were emerging across Africa as neoliberal austerity returns. Unique among intellectuals, I’d seen his central role in advisory sessions over the prior two decades with the likes of Castro, Chavez and the world’s most respected grassroots activists—and there is truly no one to take his place.

Amin’s best-known books came at the height of dependency theory’s popularity during the 1970s: Unequal development; Accumulation on a world scale; and Imperialism and unequal development. His book Eurocentrism hit a nerve in 1988, and in 1990, Delinking summed up why the still young era of globalisation would further underdevelop Africa, and why a more self-reliant strategy was necessary. Amin’s memoire, A Life Looking Forward, was published in 2006 and contains delightful tales of youth, professional score-settling of a political-intellectual nature. More recent books include Ending the Crisis of Capitalism or Ending Capitalism?; Global History; Capitalism in the Age of Globalization; and The Law of Worldwide Value. In these, Amin became as ruthless a critic of extreme Islam and other dogmatic religious movements, as of neoliberal imperialism.

On occasional visits here in south Africa, Amin expressed dissatisfaction with the many concessions made to capital, regretted that Africa’s most capable industrial base was destroyed by excessive liberalisation, and complained that Pretoria officials were too willing to relegitimise Western economic power.

The main merit of Marxist analysis, Amin argued in 2016, is its “claim simultaneously to understand the world, our capitalist global world at each stage of its deployment, and provides the tools which make it possible for the working classes and the oppressed peoples, i.e., the victims of that system, to change it.”

Paulo Nakatani, Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil [top]

I personally met Samir Amin in 2002, participating with him in examining jury to obtain the diploma of Habilitation pour Diriger les Recherches (HDR) from Professor Rémy Herrera. However, for me, one of my first references to him was his book Accumulation on a World Scale, published in Argentina in 1971. At that time, I was still in college studying in the career of economics. Brazil was going through one of the most difficult and repressive periods of the military dictatorship. There was a great censorship against left-wing and Marxist publications of books and journals. For this reason, there are few Samir books translated and published in Portuguese to this day. Even many Brazilian Marxists knew little about their work.

After this first meeting, in 2002, I was invited to participate in some meetings of the World Forum for Alternatives, through the recommendations of Professor Rémy Herrera. Unfortunately, I didn’t get the chance to have a very close and deeper friendship relationship with him because of the few times we had meet in person. In addition, I was very involved with the training of heterodox economists in Brazil, I was the editor of the Journal of the SEP and the direction of the Brazilian Society of Political Economy (SEP), which we founded in Brazil in 1996. I also had participation in the organization and foundation of the Latin American Society of Political Economy and Critical Thinking (SEPLA).

Samir Amin was a simple man, very friendly and accessible. He did not use his intellectual and theoretical weight and importance, as well as his role as a widely respected political activist around the world. He treated me like he was already an acquaintance and friend. So even without having a closer relationship with him, I considered him a personal friend. At the same time, He was a master with whom I always learned a lot of new things.

Samir Amin was a Marxist intellectual known and respected to all who defended the revolutionary need to overcome the capitalist mode of production. Unfortunately, he was less well known in Brazil. His theoretical contribution in various fields of knowledge is invaluable. However, for me personally, Samir’s most important contribution is in the field of political economy, from the debate on capitalist development, the debates between the conceptions of center and periphery, development and underdevelopment and unequal exchange, and also since the 1970s to the most recent formulations, such as the senility of capitalism and the need for its revolutionary overcoming. In addition, it allowed me to review and reconsider issues about transitions to socialism, in particular about the ongoing processes in China and Cuba to which I have dedicated part of my studies in the last years.

Pedro Páez Pérez, The Central University of Ecuador, Ecuador [top]

Very early as undergraduate in Economics I read the Spanish version of Samir Amin’s Capital Accumulation on a World Scale, not without a lot of discipline, but plenty of enthusiasm. The hard task was worthy because it brought me a possible axis of coherent distinction between the opposite sources of my previous militant study of Marxism and Dependency Theory and my ongoing training in the technical courses of “Conventional Economics” assimilated in the interest of the most vulnerable ones.

His critical perspective helped me later to undertake further explorations in the specialized literature on Economics (the debate on Unequal Development and Exchange, the evolution of Imperialism and the worldwide formation of values), and History (especially the characterization of the Inca Empire in the framework of the tributary modes of production, Eurocentrism and the contrasting types of colonialism and the role of peasantry and landlords in the class alliances within capitalism that define underdevelopment and the strategies of overcoming it).

A couple of decades later, when I finally met him personally, I had accumulated such an amount of interrogations (both political and theoretical ones) that I hardly had time to argue in favor of my first priority then: the urgent need of New Domestic, Regional and Global Financial Architectures as pivotal steps towards any strategy of Delinking. I had the luck and honor to meet him several times during the next few years to profit out of my dissidences and his generosity.

Always plenty of discussion points and discrepancies, we had several days to intensely share when he kindly invited me to his 80th birthday. I think I managed to convince him about the specificity of monetary, macroeconomic and financial issues in a transformative horizon, at least as a minimalist component in a broader agenda and more so in the midst of the financial implosion of this structural crisis of capitalism. He remained skeptical about the viability of wider social alliances and the transition processes referring to innumerable historical experiences in different latitudes but also regarding the sharp decomposing derive of American Imperialism. Inevitable harsh times should open a new epoch of radical changes rather than futile reformisms, despite their good intentions, both in the Global South or in the North.

His overall positive perception of the progressive governments in Latin America and the role of China and Russia contrasted in an unfavorable comparison with the radical transformations promoted by anti-colonialist movements and the Bandung Spirit decades ago, even so he stressed his contemporary and hindsight criticisms of the latter (he suffered political persecution under Nasser). Very critical of most of the new waves of what he called social-liberal, neo-pantheist or postmodernist branches of the recent Left, he emphasized the need for a higher theoretical and political synthesis of every struggle for emancipation under the centrality of class exploitation. Thus, the path of unity around an anti-neoliberal front must transcend mere Keynesian, nationalist or re-distributive policies and take advantage of the integral nature of today’s capital decrepitude to propose a New Civilization.

A large but disperse community all around the world agree with him on the magnitude of the challenge and the delicate equilibrium required due to the anti-social ferocity of the decadent Imperialism and the crucial tactical role of policy space expansion for every nation, especially in the framework of South-South cooperation, but based on social mobilization and political inclusion. I witness his last and unfinished efforts devoted to build an international network of progressive forces fit to these tasks.

His physical absence demands a deeper commitment of intellectuals in the organic construction of alternatives facing this crisis of capital that so immediately jeopardizes Humanity’s dignity and even survival.

World Forum of Alternatives (WFA) conference in Paris, 2002. WFA members, from right to left: François Houtart, Samir Amin, Víctor Hugo Jijón, Firoze Manji.

Víctor Hugo Jijón, Commission for the Protection of Human Rights, Ecuador [top]

I met Samir Amin at an international seminar of social organizations, research centers and intellectuals held in Paris in 2002, in order to analyze the concrete actions that the World Forum of Alternatives, WFA, could develop after his participation in the World Social Forum that had been held in Porto Alegre, Brazil. I had read some of his books and it was very important to discuss with him practical matters to achieve the objectives of WFA for supporting the convergence processes of social movements and the emergence of democratic, plural and durable alternatives to neoliberal globalization and different forms of discrimination or domination. Subsequently, we formed a work team that monitored various activities of the WFA.

My friendship with Samir was excellent, with relative continuity despite the fact that we did not live in the same city, he in Paris or Dakar and me in Quito. He always showed interest in knowing the Latin American reality better and we frequently exchanged economic, social or political information about this region by internet. I also had the honor of meeting and talking with him on several occasions in his apartment when I was traveling to Paris.

Among the international events of the WFA where I had the opportunity to share reflections and debates together with Samir and François Houtart, Executive Secretary of the WFA -who unfortunately passed away a year before Samir- are: an International Seminar in Quito, in 2012, where it was analyzed the “Project for the Universal Declaration of the Common Good of Humanity“; the Algiers Colloquium in 2013; and the Tunis WFA Congress in 2015.

I think he was a man who dedicated his life and his theoretical work, like his political praxis, to the service of the countries of the South and their post-independence emancipation from the colonial heritage. Samir Amin was probably the only economist known from the Third World and studied at universities around the world.

Several generations of students, researchers, academics and intellectuals from Dakar to Jakarta, from Cairo to Sao Paolo and from Paris to Beijing have been trained to read the major works of Samir Amin. Whether on the world economy, development, political evolution, or on Islamism or neoliberalism, his work is always a guide to liberation. But his research activities have never alienated Samir Amin from activism and political engagement. And all this while leading a modest and generous life.

Samir Amin has broken the closed universe of economic thought which is often a completely opaque and closed discipline for many people. Samir raised three different but related issues: his vision of the world and the possibilities of changing it; its conceptual and political proposal around the implosion of capitalism and its disconnection; and the analysis of the world context, seen especially from the Middle East and Africa, but which extends to an emancipatory perspective from the South. He contributed to the reflection on another more solidarity and equitable world long before the alterglobalists were in fashion.

A constant concern of Samir was to reconstitute a united front of workers on an international scale in the current structural conditions of the organization of work, very different from those of 30 or 40 years ago, with a monopoly capital that has benefited from neoliberalism , the disappearance of the Soviet Union, the technological revolution, precariousness, relocations, the dissemination of the production process, the irrational exploitation of natural resources and the degradation of biodiversity. Therefore, he proposed that “It is imperative to reconstruct the International of Workers and Peoples.”

Wim Dierckxsens, International Observatory of the Crisis, Holland/Costa Rica [top]

200 years after the birth of Marx, one of the most prominent Marxist economists of the 20th century passed away on August 12, 2018, just at the time he was about to board the plane to receive the title of Doctor Honoris Causa from the National University de la Plata –UNLP- in Argentina. At the same event, the book La Crisis Mundial: Continentalismos, Globalismo y Pluriversalismo, written by Walter Formento and myself with a preface written by Samir’s hand, would be presented.

The first time I met Samir was at World Forum for Alternatives (WFA) in January 1999 in Switzerland during a meeting of WFA called ´The Other Davos´ where Samir gave a press conference, in front of the hotel where the World Economic Forum took place at that moment. In his conference Samir called for the convergence of struggle and resistance against globalization. I was invited because of my book The Limits of Capitalism (published by Zed Books, London) Samir himself presented in Italy. WFA participated in most of Word Social Forums (WSF). We had regularly meetings in ´Centre Tricontinental´, Louvain la Neuve, Belgium together with François Houtart. In 2006 was founded International Crisis Observatory (ICO) with Samir as honorific president and myself coordinator till now.

What most impressed me is that Samir did not opt in the first place to have a brilliant academic career after his Ph.D, but to insert himself in socio-political life with a profound interest in political economy and historic materialism at service of political action from below. I´m sure World Forum for Alternatives (FMA) was Samir´s principal work of his life, a Forum he directed together with François Houtart till their last breath.

Samir had a very up to date vision. He considered that the structural crisis that contemporary capitalism is going through is not a transition to be overcome by a new phase of globalized capitalist expansion, as he points out in his book Beyond Senile Capitalism (2002). Much of the problem tackled by him, during more than fifty years of intellectual work, focuses on “the long transition to communism.” In his book ´For a multipolar world´ in 2005, he poses the challenge of building a multipolar world for the transition towards social and democratic progress throughout the world. Along these lines, we share thinking such as The Disconnection, Towards a Polycentric World System. In 2005, Samir points out, as if he is here and now, that Russia, China and India are the three strategic adversaries of the unipolar project, but that the deployment of the European project is not going in the necessary direction, that is, it does not look (yet) to the East.

Samir strongly believed that only by bringing the unipolar project to failure (nowadays possibly the case), it will be possible to advance towards a multipolar world and consider new social achievements on the way to overcoming a capitalism that has entered the terminal phase. It is in this direction I have worked even before I met Samir and which was the reason to share visions. He vindicated a new internationalism of the Asian, African, Latin-American and European peoples. This systemic crisis will bring opportunities and as Samir would say to us, we have to work and struggle as if this crisis is really the last crisis of capitalism.

‘Helped orient my generation’

Vijay Prashad, Executive Director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research [top]

I met Samir Amin at several conferences and meetings. He was a charmingly bright man, generous to younger people and determined to guide. From Samir, I learned how to navigate the conjuncture, how to think as a Marxist in political terms. For instance, his short columns on China and on globalisation helped orient my generation at a time when we saw older certainties collapse. Samir’s major books—notably Accumulation on a World Scale and Delinking—taught us about the geography of imperialism, and about the need to think of policies that were attainable and necessary (such as delinking); these strategies, at the tactical level for governments such as capital controls, remain a necessity. It is by chance that Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research was the last to interview Samir, and that interview is our first Notebook. We called that text Globalisation and its Alternative, a very fitting title. I miss his wisdom.

Samir Amin (bottom row, left) with a group of intellectuals, including John Bellamy Foster (bottom row, right), in Vietnam in December 2009.

Personal Recollections and Intellectual Remembrances

John Bellamy Foster, editor of Monthly Review and Professor of Sociology at the University of Oregon

I first met Samir Amin at the Monthly Review office in New York in the 1980s, through Monthly Review editors Harry Magdoff and Paul Sweezy. He was pleased with my treatment of his work on imperialism in my book Theory of Monopoly Capitalism (1986). We remained in touch over the years, corresponding on occasions, particularly after I became coeditor and then editor of Monthly Review, beginning in 2000. Amin stopped visiting the United States altogether, but we met abroad at various times over the years, in Mali and Vietnam. In Mali I participated with many others in writing The Bamako Appeal under his leadership. In Vietnam we met with the government. Beginning in 2010, he asked me to be the Vice President (from the United States) of the World Forum for Alternatives/Forum Mondial des Alternatives. Given the importance of this organization I agreed, although my role was mainly honorific.

From the 1980s on Monthly Review and Monthly Review Press were the main publishers of Amin’s writings in English (although important works were also published by Zed Press in London). Amin was crucial in helping to define our whole perspective, particularly on imperialism. At Samir’s request, I wrote a foreword to the second edition of his Capitalism in the Age of Globalization (Zed, 2014). We worked in tandem in his final years when he was writing Modern Imperialism, Monopoly Finance Capital and the Law of Value (2018) and related works, in which he expanded in part on the ideas of Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy in Monopoly Capital (1966).

Amin’s signal contribution from a political-economic perspective was his theory of worldwide value, summing up the system of unequal exchange/imperial rent dividing the Global North and the Global South. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, the concentration and centralization of capital, noted by Marx, was, in Amin’s view, manifested in the growth of the phase of generalized monopolies or monopoly finance capital. Capital had become more and more mobile (along with technology), as the giant firms become increasingly globalized and financialized. Nevertheless, the nation-state divisions remained intact with governments promoting the interests of their corporations over those of other countries, along with restrictions on the mobility of labor. The result is a system of unequal exchange, in which the difference between the wages is greater that the difference between their productivities. This gives rise to a system of imperial rents accruing to the global corporations and their respective states in the center. All of this points to the disproportionate exploitation of labor in the periphery, which receives compensation far below the average wages globally, and out of line with its productivity. The fact that labor is rewarded differently in the center and the periphery, and that this is related to the globalization of monopoly capital, constituted, for Amin, the essence of the imperialist world system today. It constitutes the main obstacle to the unity of the international working class, and the reason why the struggle against capitalism and imperialism must begin with a South-South alliance.

His other major contributions, in my view, include his theory of Eurocentrism, including his analysis of class and nation, his recognition of global ecological inequality, and his theoretical proposition that the critique of the economic laws of capitalism is subordinated to historical materialism as a whole. No one was better at describing the fissures dividing the world under late imperialism, or how to surmount them. His prologue to his final book, The Long Revolution of the Global South represented a final summary of this views. His most urgent message at the end of his life was the need to form a Workers and Peoples International. Those engaged in the world struggle against capitalism and imperialism should heed his call.

More on Samir Amin [top]

A selection of Samir Amin’s works and videos can be found at Global University for Sustainability website.